George Brown was one of the most flagrant absconders from Moreton Bay. And, like his namesake Sheik Brown, his story is extraordinary.

George Brown was said to have born in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) around 1800, and was a seaman and servant by trade. Like Sheik Brown, he was an indigenous Sri Lankan or possibly mixed race (Moreton Bay’s convict A-Z lists him as simply “a mulatto”, whereas everywhere else he is “a man of colour”). Later descriptions have him as born in Madras, India.

Working as a sailor got him to Lancaster in 1815, where he was convicted of fraud, and sentenced to seven years’ transportation – at about 15 years of age. He enters Australian records as being disembarked from the ship “Ocean” on 5 February 1816, and forwarded to Liverpool for assignment to work. Brown appears on the list of Settlers and Convicts in 1816 and 1817 as a resident of New South Wales.

By 1820, Brown had gone to Hobart Town, and appeared on the Tasmanian Convict Muster of that year. The following year, he is listed as being back in New South Wales. An entry in the Colonial Secretary’s Papers from August 1823 goes some way to explaining this:

New South Wales. Cumberland, to wit. George Brown (a man of colour) who arrived in this Colony in the Ship Ocean (1) in 1816, being duly sworn saith “that about the latter end of the year 1817, I was forwarded with other prisoners on the Ship Pilot to Hobart Town, where I received a certificate for my sentence having expired; that shortly after I cleared out from Hobart Town, in the Ship Southwark for Batavia and returned to Sydney Cove in her, and received my discharge; that while on the voyage from Hobart Town to Batavia, I burned my certificate by the order of Captain Sampson, alleging that it was of no use to me as I never intended to return to New South Wales. I further swear that I have not sold or disposed of the said certificate in any manner whatsoever.”

George Brown, X, His Mark.

A likely story. Brown’s sentence didn’t end until 1822, and he was back in New South Wales in 1820. (Batavia was in the then Dutch East Indies – present day Jakarta.)

George Brown did receive his Certificate of Freedom on 5 August 1824. He might as well have burned that one, because on 25 August 1824, he was fully committed to take his trial for Stealing Wearing Apparel. Early the following year, Brown was transported to the Port Macquarie Penal Settlement – listed in the 1825 New South Wales General Muster as “in gaol”.

Lessons were clearly not learned, because in October 1828, George Brown was convicted at Windsor Quarter Sessions for stealing a watch, a seal and a key. Taking a stern view of a repeat-repeat offender, the Court sentenced Brown to Moreton Bay for 7 years.

George Brown arrived at Moreton Bay on 29 January 1829, one of 137 male prisoners arriving in the Bay per the ship “City of Edinburgh”. Captain Logan was in charge of the settlement, and conditions were famously harsh at that time. Accounts were starting to appear in the Sydney newspapers of poor rations, overwork and harsh discipline. The Editor of one paper in particular, The Sydney Monitor, had something close to an obsession with the settlement, and printed any extreme account or rumour. The more restrained publications, though, had by this time started to take negative notice of Moreton Bay.

Brown first absconded on 4 August 1830, staying out for several weeks. Discipline on return did not deter him, though, and he ran again on 18 January 1831, and spent 6 months out of the settlement. To spend such a long time in the bush, with no nearby towns or settlements to find food or shelter, Brown would have needed incredible outdoor survival skills, or help.

At some point, George Brown was accepted and assisted by the indigenous people of the Moreton Bay region. Being dark-skinned may have helped. Being adaptable, a legacy of a life that ranged from India and Sri Lanka to Lancashire, then Sydney , Hobart, Port Macquarie and Moreton Bay, would have helped even more. Brown was able to adapt to the languages and customs of the groups he was with, and stayed out of the settlements for increasing periods.

In 1832, George Brown absconded for another 6 month period. In 1833, Brown escaped again, spending from 27 September 1833 to 12 July 1835 with the indigenous people.

The reception Brown received in Moreton Bay was 250 lashes – an extreme punishment for running away 4 times. Another prisoner with 7 escapes on his record received 300. It is surprising that either survived. It is more surprising that it did not deter Brown, because in January 1836, off he went again.

In May 1837, information was given to the Commandant, Foster Fyans by aborigines living on Bribie Island just north of Brisbane that there were four escaped convicts living among them. It seems that the aborigines were not pleased to have these men in their midst – there have been accounts of bushrangers treating indigenous women very badly, to the extent that the groups pleaded to Moreton Bay authorities for the removal of these interlopers. The escapees in question were William Saunders (Larkins), James Ando (Guilford), George Brown (Ocean) and Sheik Brown (Asia).

Commandant Fyans gave the indigenous men a reward for accompanying Lieutenant Otter (who had coordinated the rescue of Eliza Fraser the previous year), and Mr Whyte on a journey to the Island to apprehend the escapees.

Of the four escapees, Saunders was seen as the worst character, and was sent to Norfolk Island forthwith. The reception Brown received in Moreton Bay this time was 200 lashes.

George Brown’s fortunes seemed, finally, to change as the penal settlement prepared to close in 1839. On 03 November 1838, he was discharged free and petitioned to remain in the Moreton Bay area as ‘George Brown (Ocean 1), native of Trichinopoly (Madras) and a man of colour’.

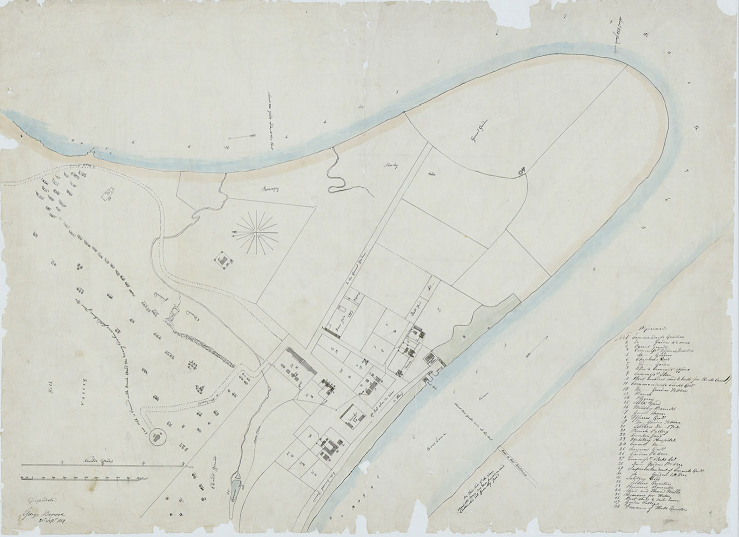

His many travels throughout the Moreton Bay area paid dividends when he was commissioned to draw a map of the layout of Brisbane. Over the years, a talent for layout and drawing had developed, and at least one of his works is kept at the Queensland State Archives.

Brown’s affinity with the indigenous people of Moreton Bay also served him in good stead, and found him paid work – as a Government employee. A Constable, no less.

1839: 02 April 1839, Colonial Secretary’s Office, Sydney NSW

Sir

I have had the honour to receive and to submit to the Governor your letter of the 13th ultimo, No. 39/9 and in compliance with your recommendation, I am directed by His Excellency to inform you that the man named in the margin (George Brown), should, on the expiration of his Colonial Sentence, by all means, remain at Moreton Bay, and be taken into the pay of the Government as a Constable, as he is stated to possess a most remarkable influence over the Black Natives.

I have &c., E D J

Colonial Secretary’s correspondence 39/3453

Sadly this happy situation did not last long. In September 1839, Commandant Gorman had the first hint of trouble. Constable Brown had led a party with three fellow constables – Giles, Eagan and Thompson – with a warrant to apprehend two escapees.

Initial reports to the settlement stated that the leader of the party, Constable Brown, had deserted the party and gone into the bush with three indigenous men at Fraser’s Creek.

SOME time since we stated that a party had found their way overland from Moreton Bay to the settlements at New England. We give further particulars, derived from the documents of the parties themselves. It appears that on the 27th of August, three convicts, named Thompson, Egan, and Giles, under the conduct of an emancipated convict named George Brown, a native of India, and accompanied by three native blacks, were despatched from Moreton Bay by Lieutenant Gorman, to endeavour to discover the possibility of a communication between that settlement and the stations about Byron’s Plains, New England. They arrived at the head station of Peter McIntyre, Esq., at Byron’s Plains, on the 13th of September, where they rested till the 17th, when they started on their return journey; when Brown arrived at Frazer’s Creek, only seven miles from the station, he slipped away from his companions, taking all the flour and supplies, and also the blacks, and has not since been seen or heard of. South Australian Record and Australasian and South African Chronicle.

The constables who had worked with him were promptly sent to Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney, while somebody worked out what to do with them. Brown returned to Brisbane Town a little later, “alone with a native”, and a story of becoming separated from the others after they were rationed. He was grudgingly believed, and the Commandant realised that constables Egan, Giles and Thompson were in Sydney with 2 firelocks and 30 rounds of ammunition belonging to the force at Moreton Bay. It was hastily decided to return the men to Brisbane and their jobs, which they had been quite good at really. And can we have the weapons we accidentally left you with, please.

Less than a year later – August 1840, Constable Brown was dismissed and sent via the “Harlequin” schooner to Sydney. He was ordered not to return to the Moreton Bay area. He had been a free man for nearly two years, but his “affinity with the natives” had turned into a bad “influence with the natives”, and it was believed that he stirred them to rebel against Europeans. He was still free, but had to find a living in Sydney. Perhaps his past as a sailor might help.

Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser (NSW : 1838 – 1841), Saturday 24 October 1840, page 2: Robbery -The Steward of the steam ship Victoria some time back, engaged a dark man named George Brown, as an assistant steward, whose duty it was to attend upon the passengers in the fore part of the vessel – after making one trip to Maitland, on the return of the vessel to Sydney, Brown absconded, and is charged with taking £9 in cash and a quantity of brandy, the property of his employer. Two or three trips to the Hunter have been made by the steamer since, and on her return to Sydney on Thursday last, the prisoner was recognized on the Commercial wharf, and given into custody. He will undergo an examination at the police office this day.

He was discharged for lack of evidence the following day. Still free. Employment prospects poor.

On 30 October 1840, George Brown received his Certificate of Freedom. The document, of course, described him as “a man of colour”, with tattoos of a crucifix, WF Heart pierced by darts on the inside of his lower left arm, and some illegible letters on his upper right arm.

In November 1841, a series of attacks on property by indigenous people in the Bathurst area caught the attention of the authorities, who notified the Commandant at Moreton Bay. One of the men arrested was one George Brown (Ocean 1), who was charged with larceny. Depositions were taken from hutkeepers to the grazier George Mocatta, who identified Brown as the cause of the unrest, due to his “influence with the natives”.

In February 1842, George Brown makes his last definite appearance in the official records as he waited for his trial on the larceny charge. This time the Description Book of Darlinghurst Gaol unkindly described him as “stout” in addition to the usual identifiers.

He must have been tired of the losing battle with the law in Australia.

Sources:

New South Wales, Australia: Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1856. Moreton Bay: Letters from the Colonial Secretary to Commandant 1832-1853, State Records Authority of New South Wales.

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930. Description Book, Darlinghurst 1841-1849, State Records Authority of New South Wales.

Certificate of Freedom. 05/08/1824

Certificate of freedom. 30/10/1840 n0. 40/1784

Convict Muster, New South Wales, General Muster A-L, 1825, 1821, 1817, 1816, Convict Muster, Tasmania: List of convicts (incomplete), 1820.

Architectural Plans: Layout of Brisbane Town, Moreton Bay 20/09/1839. Series ID 3739, Item ID 659605, State Archives of Queensland

CS Reference: 37/05416. CS Reference: 38/06900. CS Reference: 39/5853.

CS Reference: 39/09240. CS Reference: 39/09243. CS Reference: 39/03453.

CS Reference: 39/0553. CS Reference: 38/06907.

CS Reference: 38/06907.

Letter to Hon Colonial Secretary from Crown Commissioner’s Office, New England, 20.09.1839. Letter to G.J. MacDonald, Commissioner of Crown Land, new England, from J. Cameron, Bundarra.

Letter to Hon Colonial Secretary from Moreton Bay, O Gorman, Lieutenant 80th Regiment, Commandant. Dated 13.08.1840 and 02.09.1840.17.09.1839. 1839.11.16

To Hon. CS from Crown Commissioner’s Office, New England, GJ MacDonald, Commissioner. 1839.09.24.

Letter to Hon Colonial Secretary from Surveyor-General’s Office, SA Perry, Deputy Surveyor General. 1840-10.09.

Letter to Hon Colonial Secretary from Arthur Hodgson dated 27.10.1841,

Letters Received 1841 – 1842 and papers filed with them. 01.01.1839, 01.01.1840 Reel A 2.12, pp 257 – 258.

Hi,

Brown was not captured in Bathurst as far as I am aware, because George Mocatta was at Grantham in the Lockyer Valley of the Moreton at this time. His Superintendant James “Cocky” Rogers led the mission to capture Brown and when they raided Brown’s camp he was caught red-handed, sound asleep on a big pile of sheepskins gathered from the sheep he had stolen from Mocatta.

In 1875, the pastoralist C. W. Pitts penned an article for the “Christmas Supplement” in the Darling Downs Gazette, which recounts the events of November 1842 (sic.). It appears by this time Pitts must have forgotten that the Grantham raid had actually taken place in the previous November (i.e. of 1841).

Pitts explains that the Grantham raid had primarily been organised to address the problem of an escaped convict named George Browne who had been living among the Aboriginal people and causing significant problems for the squatters. The squatters believed Browne had been actively aiding and abetting the Aboriginal people in their plunder of the settler’s stores, supplies, and livestock.

The raid on the camp had been carried out by James “Cocky” Rogers, superintendent of George Mocatta’s station, M. T. Somerville from Tent Hill and their servants, armed with muskets and on horseback (Evans, 2007, p 53).

The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld. : 1858 – 1880) Fri 24 Dec 1875 Page 1 CHRISTMAS AMONG THE PIONEERS OF MORETON DAY.

LikeLike

Hi Ian, thank you very much for letting me know. I missed that reference, and found it incredibly hard to track Brown down after Moreton Bay. Karen

LikeLike