Who were the men who took part in the ill-fated survey party in 1840?

Granville William Chetwynd Stapleton was the youngest son of Major-General Granville Anson Chetwynd Stapylton, born in 1800. He married Catherine Bulteel in 1825, and decided to make his career in the (very) New World in 1828, becoming an Assistant Surveyor in the Colony of New South Wales.

He made a number of successful surveys, and was recommended for promotion. A promotion of sorts was to be second in Command to Major Mitchell (after whom a type of cockatoo is named) in 1836 for the Australia Felix expedition. The men did not get on. Stapylton was left to manage depots and base camps rather more than he would have liked, and he railed in his journal of the incompetence of those in command, the character and behaviour of the convicts who worked for him, and the Aborigines he encountered. Today it might be called a toxic work environment.

Stapylton’s 1836 journal reveals a man who appeared to be in a bitter struggle against just about everything. A good deal of this was probably brought on by the difficulties of the expedition, but there is an air of entitlement- why should a man such as he labour under these conditions and deal with such oafs? Extracts from the journal can be quite entertaining to the 21st century reader.

“My tent keeper being more than ordinarily scruffy and dishevelled, I reported him to the lead GS, who gave him the devil to eat… owing to the misconduct of others of the Service (they) think all Assistant Surveyors need be but little esteemed and myself therefore to be insulted at will. The devil take Officers who have not propriety of conduct belonging to them.”

He did not like or trust the indigenous people he encountered.

“I there saw four scoundrel natives seated under the brow of a hill on my track round a little fire, scarcely smoking, and evidently lying in wait for my return. I was provoked at their cunning and villainy for they had evidently tracked me for miles, as I afterwards perceived by their footsteps and could not resist blackguarding them for a few moments.”

It is tempting to speculate whether Stapylton may have dished out a blackguarding four years later, precipitating his murder.

All in all, Australia Felix was summed up by Stapylton as follows:

“I may cursorily remark that if a friend were to ask me my sincere statement of the matter I would simply tell him, that if he wished for a foretaste of Hell, I would recommend him to apply for permission to accompany the next Expedition of Discovery under the same Commander with his 24 convicts, and that after six months experience of the system as it relates to the position and comfort of the second in command and organized as this has been according to the peculiar fashion of the Devil himself, who is at present unquestionably walking New Holland in the person of ————— I am confident he would be enabled to give a pretty correct account of what the Infernal regions present, in the shape of entertainment.”

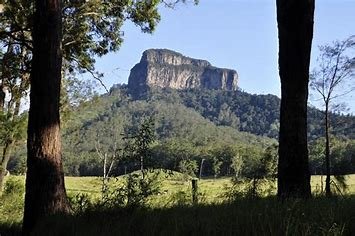

A change of scenery was needed, and Stapylton went to Port Phillip to survey for Robert Hoddle. By 1838, though, he was drinking heavily, and was dismissed. Governor Sir George Gipps came to Stapylton’s professional rescue, and found him work for Surveyor Dixon in Moreton Bay. After all of the dangers in the lands he’d travelled, he met his death at Mt Lindesay. He is interred at Toowong Cemetery, Brisbane.

The surveying party of May 1840 consisted of Assistant Surveyor Stapylton and 7 convicts assigned to the Surveyor-General’s Department. By that time, everyone in that Department knew that Stapylton was a taskmaster. Some had been punished by the Commandant at Brisbane Town for their conduct on the Logan River survey.

Abel Sutton, alias William Kirby, was a 32 year old Wiltshire man who was transported for life for shop breaking. He arrived in New South Wales in 1838, having left behind his wife, a son and three daughters because of his criminal career. He was of average height for the time – five feet four- and had brown hair and eyes, and a dark sallow complexion that stood him in good stead in the Australian sun.

When Abel Sutton joined the Mount Lindesay party, he was coming off a month in prison with hard labour for ‘neglect of duty and disobedience of orders’ on the complaint of GC Stapylton. The offence involved not seeing to the bullock driver, and as a result one bullock had strayed in the night. Sutton thought that all the bullocks were hobbled when the party turned in for the night. He’d tried looking for it, and in his defense said he’d done his best but could not succeed in pleasing Mr Stapylton.

After the horrible events of May and June 1840, the Commandant gave Sutton a good chance and got the Governor to appoint him a Constable- with the same rations of tea, sugar and tobacco as the other Constables. A ticket of leave, followed by an absolute pardon, would follow over the next two decades.

Peter Finnegan, alias John Maguire, 28, was a weaver by trade, born in County Dublin and transported for life for highway robbery. He was ruddy and freckled, also with brown hair and eyes. There’d been almighty strife with the Master on account of Finnegan’s rations. Peter Finnegan thought that he wasn’t given his proper rations and said so. He was told to go and see Mr Dixon if he thought that was the case. He did, and Stapylton charged him with making a false and improper statement. He got 10 days in solitary confinement on bread and water, and was going to be very careful in future.

Patrick Kelly was a tall, grey-eyed Kilkenny native, doing 15 years for highway robbery, He came to NSW on the Blenheim the year before. He was fresh-faced and cheeky. A little too cheeky for GC Stapylton. In January, he’d done 10 days in solitary confinement on bread and water for ‘insolent and improper expressions to Assistant Surveyor Stapylton’.

What had happened was that the Master called out to him, but he mustn’t have heard the first time, because the man kept calling for him, louder and louder. When Kelly got to the tent, he swore by the Holy Ghost that he hadn’t heard him the first time. The Master said Kelly was ‘ruffianly and disrespectful’.

William Gough, a Berkshire man barely 21, came over for life for highway robbery on the Portsea. He’d laugh with Peter Finnegan and William Gough that the Survey Department needed highwaymen to create roads in the new world. He hadn’t been charged for upsetting the master and suspected that it was only a matter of time. Stapylton never had the chance to notice Gough for anything. In 1841, William Gough, 22, joined Abel Sutton as a Constable for Moreton Bay.

William Burbury (Barberry, Burberry, Banberry – people were always getting it wrong) was a 32 year old Soldier who was Court-Martialed in Gibraltar for striking a sergeant, and got 7 years’ transportation in 1838. He knew too well what insubordination could bring, and he’d seen the like of Stapylton in the army – youngest sons of grand families all full of their own dignity. He was chief cook and bottle washer on this jaunt, but welcomed the trip to the creek that day, to get away from the Master for a bit.

James Dunlop was a youngster of 22 who’d managed to get life for coining. Pale and heavily pock-pitted, with light brown hair and grey eyes, he hadn’t given Mr Stapylton cause to get angry with him, and tended the bullock team as if his life depended on it after what happened on the Logan River survey. He had the meagrims in his head for ages after Carbon Bob hit him with the waddy. He kept his nose clean after that, and was granted a conditional pardon in 1847.

William Tuck was the oldest man on the survey. A labourer of 49 years and grey-haired with an impressive collection of arm tattoos, he didn’t take well to these overland expeditions. He had a sore leg that 31st of May 1840, so bad that Stapylton let him rest a bit in his tent. That was a kindness that would prove fatal, as he, the Master and Dunlop were attacked in the camp that morning. William Tuck was hastily buried in the bush campsite on 7th June 1840. His exact grave location is unknown.

Sources:

M Series 2014: Journals of Granville Stapylton, 7 April 1836 – 17 July 1836 (AJCP ref: https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2288214)

Book of Trials Held at Moreton Bay, 1835-1842. Item no: 869682, State Archives Queensland.

Louis R Cranfield, “Stapylton, Granville William Chetwynd, 1800-1840.” Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967.

New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents

New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence