The Moreton Bay penal settlement was designed to be a place of punishment, but not execution. There was no Supreme Court at Brisbane until the 1850s, no scaffold and no executioner. The prisoners who committed capital offences at Brisbane were taken by sea to Sydney, where they were tried, and if found guilty, executed.

The only exception to this rule was made in the case of two young Irishmen who had absconded and committed armed robbery, Charles Fagan and John Bulbridge. They were executed at Moreton Bay in 1830 as an example to other convicts.

CHARLES FAGAN

Charles Fagan, a carter from Dublin, was transported in 1822 for seven years. He blotted his colonial copybook with a robbery and then absconding from the penal settlement at Port Macquarie. The Campbelltown bench sent him to Moreton Bay for three years. The change of air was clearly not suitable to Fagan, and he ran from Moreton Bay three weeks later, on 4 October 1826, in company with William Butler and William Dalton. Fagan and Dalton were recaptured at Port Macquarie and were ordered to be returned without compliments to Moreton Bay on 01 July 1827. Butler, a 40-year-old gardener who had volunteered to Moreton Bay, was never recaptured. Whether he died on the run, joined an indigenous community or made a quiet life somewhere else is not recorded.

Charles Fagan and William Dalton arrived at the Bay on 31 July 1827, and Fagan ran again on 21 November 1827. Dalton waited another year, and then ran and returned twice more before being discharged to Sydney in 1834. He was in the middle of a three-year absence when Fagan and Bulbridge were executed in December 1830.

By February 1830, Fagan was in Sydney and made the mistake of walking within sight of a police station at 1 am with a large bag over his shoulder. The bag contained nine fowls that he had nicked from a henhouse. The Bench decided that three years at Moreton Bay was a suitable punishment. Charles Fagan, as usual, considered that a temporary arrangement, and fled again on 23 August 1830. This time his absconding partner was young John Bulbridge of Limerick, a very tall young man who also had a taste for absconding.

JOHN BULBRIDGE

Born in Limerick in 1808 and convicted there for felony in 1824, John Bulbridge was fresh-faced, and at 5 feet 10 inches stood a head taller than most men of the time. He’d done a stint at Moreton Bay in 1828 for absconding from his gang, but it was only twelve months, and it was hardly worth running away. Back in Sydney, and less than a year away from a Certificate of Freedom, he stole some timber belonging to the Crown and was sentenced to return to Moreton Bay for three years.

His criminal and absconding history was nothing to Fagan’s, but he threw in his lot with the more seasoned absconder and ran with him on 23 August 1830.

PORT MACQUARIE

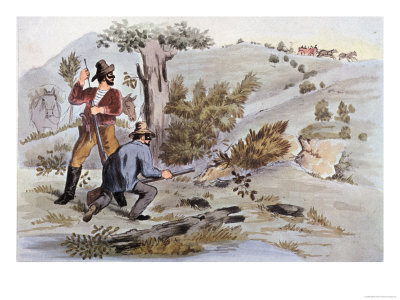

Just before sundown 26 September 1830, two tired, bedraggled and hungry men appeared at the garden convict worker Thomas Smith was tending at Port Macquarie and passed the time of day. They followed Smith into his master’s hut and sat with him, chatting for about ten minutes. Then they relieved him of his rations, some clothing, a kettle, and a gun and a powder horn belonging to his master, Barker. They didn’t threaten Smith and he did not resist – it was two men against one.

Thomas Barker was unimpressed when he returned to the hut to find his kettle, clothing and gun gone, and heard Thomas Smith’s tale of two bushrangers with some scepticism. He later identified as his the property found with Fagan.

Thomas Barker was unimpressed when he returned to the hut to find his kettle, clothing and gun gone, and heard Thomas Smith’s tale of two bushrangers with some scepticism. He later identified as his the property found with Fagan.

Two days later, Michael McGragh, the ferryman at Blackman’s Point, Port Macquarie was alerted by his dogs barking at about 10 at night. He opened his door and saw two men leaning against the doorframe, one had a stick and the other rested a gun on his arm. McGragh asked the men where they were headed, and they replied Balingarry, about 10 miles away. McGrath’s co-worker, Thomas Breen, came up and the two men begged for some food. Breen and McGragh relented and let the men in to eat some beef and bread. They knew the men must be bushrangers – they were hungry, armed and unkempt. One of the men laid his gun down on the table to drink from a tin cup, and McGragh saw his chance. He seized the weapon and hit the taller of the men with it, in a blow that broke the gun. The two men leapt to their feet, one grabbed a spade, and the other a knife that was on the table. There was a struggle, but the two men got away.

The next time McGragh saw the men, one was in custody of a soldier and some indigenous men – that was Fagan, he later found out. McGragh didn’t see Bulbridge until he was brought in to the settlement to identify the men and some stolen items found on them.

COMMITTAL

When the two absconders were brought before the Port Macquarie Commandant charged with entering government property, stealing and putting the inmates in fear, the men claimed to have witnesses, and those men were prisoners. They would not name the prisoners at that stage, because it was dangerous for a prisoner to give evidence in support of another prisoner. Bad things happened to those men. They would name them later.

The Commandant called upon them again to give the names of their witnesses to be subpoenaed for their trial in Sydney. He told them that they would not be allowed to call those men when they got to Sydney – it would cause unnecessary delay to their trial. The Commandant even read them a section of the letter he and other Commandants had received from the Colonial Secretary, stating that prisoners would no longer be allowed to delay trials by claiming that their witnesses were not ready. Michael McGragh, watching in the courtroom, testified that the men seemed to understand what they were being told, but would not be moved.

TRIAL

At the Supreme Court in Sydney on 26 October 1830, Fagan, the older and more talkative of the prisoners, conducted the defence and cross-examined witnesses. The men were not legally represented. Fagan addressed Justice Dowling on their witnesses not being called and stated that they could not name the witnesses before the Commandant, because prisoners were afraid of reprisals if they were known to be giving evidence.

Mr. Justice Dowling— Stop, prisoner, I will not allow you to go on. I should be extremely unwilling to force you on your trial, if I could see any just pretext for staying it, but I think I should be departing from my duty, after the evidence laid before the Court of the opportunity given you to call your witnesses, and your having been warned of the consequences of your neglecting to do so at the proper time, to put off your trial.

The Crown witnesses then began to give evidence as to what they had seen on the 26 and 28 September 1830.

Fagan challenged McGragh, saying the man was a prisoner sent there for life and would be just as likely to have committed the robbery as he. He also challenged the identification of the stolen items in cross-examination but did not put up a defence case.

Justice Dowling, aware that the men had no lawyer and had put themselves in jeopardy of their lives, summed up at length. The jury retired for “a few minutes” before finding both men guilty. A sentence of death was passed on Bulbridge and Fagan, who seemed resigned to the fact. Fagan, thinking he would meet his maker shortly in Sydney, asked that a friend be allowed to visit him before he died. The judge referred the request to the Sheriff’s office.

MORETON BAY

The prisoners did not receive the swift punishment that other condemned men in Sydney could expect.

In 1830, runaways from penal settlements, particularly Moreton Bay, were an ongoing problem. The Colonial Secretary and the Sheriff corresponded about the idea of sending the men back to Moreton Bay to be executed, to make an example of them.

Eventually, it was decided to send Fagan and Bulbridge to Moreton Bay to die. The Deputy Sheriff, the Constable in Charge and the Executioner would also require passage to that place. The Commandant of Moreton Bay, Captain Clunie (who had replaced the recently murdered Patrick Logan), was instructed to have his prisoners build a scaffold. The Colonial Secretary further instructed that as many prisoners as possible should witness the execution, together with a strong detachment of soldiers, to prevent unrest.

On 17 December 1830, Rev. John Joseph Therry of the Chapel House, Sydney, wrote to the Colonial Secretary, advising that no clergyman would be sent to Moreton Bay to attend the prisoners, as a protest at the harshness of the sentence. Therry was the clergyman who attended the Catholic prisoners in Sydney, and the two men to be executed were of the Catholic faith.

The sentence was comparatively harsh – men were doing three to seven years at Moreton Bay for manslaughter and murder – something Fagan and Bulbridge would have reflected on before their deaths. Therry’s disquiet over the sentence was understandable, and to have written to the Colonial Secretary stating just that would have caused a sensation in bureaucratic circles. It did nothing, however, for Fagan and Bulbridge, who had to leave the world without the comfort of a priest in attendance.

Fagan was 25 and Bulbridge 23 when they were executed.

The scaffold, used once, was torn down, and the men were buried outside the fence of the prisoners’ cemetery on what is now North Quay and Tank Street.

The next prisoners to be returned to Moreton Bay to be executed as an example to their kind were the indigenous men, Meridio and Nengavil, who were convicted of killing Granville Stapylton and William Tuck at Mount Lindesay a decade later. See: Murder at Mt Lindesay 2

Sources:

1 Comment