DEATH. MALLALIEU. —On the 21st June, at Adelaide-street, Constance Mallalieu, aged 10 years, eldest daughter of Alfred and Henrietta Mallalieu. [Manchester papers please copy.]

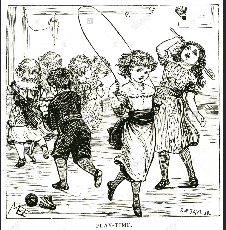

On 19 June 1873, a group of young girls played with a skipping rope after school, on a hillside at the corner of Edward and Adelaide Streets. Two girls held the skipping rope, and the other two, Constance, aged 10, and Emily, aged 11, jumped in and out. A few other girls were milling about, getting a little bit of fun in before they went home to their homes and their chores.

On 19 June 1873, a group of young girls played with a skipping rope after school, on a hillside at the corner of Edward and Adelaide Streets. Two girls held the skipping rope, and the other two, Constance, aged 10, and Emily, aged 11, jumped in and out. A few other girls were milling about, getting a little bit of fun in before they went home to their homes and their chores.

It appeared that Constance fell or was pushed over, and another little girl thought she saw Emily knock the other girl down and kick her but didn’t see the whole episode.

Constance, who had seemed well earlier in the day, returned to her Adelaide Street home crying, complaining of pain in her head and side and telling the family maid that someone had thrown her down and kicked her on her way home from school. Constance’s mother gave her a little chlorodyne (a patent medicine generally containing laudanum, tincture of cannabis and chloroform), and put her to bed. The maid took away Constance’s clothes, which were a little dusty, but not muddy, as one would expect from a fall in an unpaved street after some rainstorms earlier in the day. A little more chlorodyne may have been administered.

Constance’s health did not improve, and Dr Hobbs was sent for at 11 pm that night. The girl remained ill in bed until she died just before midday on Saturday 21 June 1873. Her family was understandably devastated.

Dr Hobbs performed a post-mortem examination that afternoon. It was his belief that Constance died of pleurisy brought on by being kicked in the ribs. There were no marks on the child’s body, but Dr Hobbs believed that stays and thick clothing prevented the appearance of bruising.

Emily was arrested for manslaughter and put into custody in the cells at the Police Court.

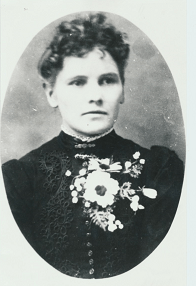

Constance was the ten-year-old daughter of Madame Mallalieu, nee Henrietta Willmore, a distinguished musician and teacher who had arrived in Brisbane with her husband and first child in 1862. Mme. Mallalieu was a successful concert pianist initially but took up her long and distinguished teaching career when M. Mallalieu suffered a business setback in 1866. Emily Penfold was the daughter of a hairdresser named David Penfold and was a native of Brisbane Town.

On Thursday 26 June, one week after the girls’ skipping game, Emily Penfold, 11, appeared in custody before the Police Magistrate, charged with manslaughter.

Florence Adelaide Wilson aged 9, having shown that she knew the meaning of taking an oath, testified that she went to the Brisbane Normal School with Constance and Emily, and saw Emily hit Constance on the shoulder and then kick her twice, causing the girl to run home crying. Under examination, Florence admitted that she had been about 20 yards away, and that there were other children in between, but she did see Constance on the ground and that the child may have rolled down the hill a little after falling. She added that Constance’s clothes would have been muddy from the rain.

Dr Hobbs gave evidence about Constance’s condition. She had been conscious that first evening, but her breathing was short and painful. When she died, a post-mortem revealed pleurisy and congested lungs, but no external bruising. Dr Hobbs believed that a kick to the ribs could have induced the pleurisy that killed Constance, who, apart from being quite thin, was otherwise a healthy little girl.

The committal of Emily Penfold continued the next day. Her teachers were called to give evidence about the presence of both children at school that day, and roll books were tendered to the Magistrate.

Madame Mallalieu’s maid was called to describe Constance’s clothing for school that day. She wore – in the mild sub-tropical winter – “soft corded stays (thick), and petticoat with thick body, and yellow dress with a body, and white jacket”. Her clothes were a little dusty but not muddy.

A little girl of 7, named Elizabeth Davidson, having taken the oath, stood on a chair to be seen in the witness box and recalled the two girls together at the corner, but became hopelessly confused when examined as to the day she had seen them.

The Magistrate decided not to decide on the matter and sent it to the Supreme Court. It would be better for a jury to hear and decide the case, he felt.

Emily Penfold was remanded in custody for a Supreme Court Trial in September. The Magistrate decided that she could be in the care of the watch-house keeper during that time, rather than put in Brisbane Gaol with all the adult offenders.

On 01 September 1873, Emily Penfold faced Justice Lutwyche and a common jury in the Supreme Court. The Attorney-General arrived to prosecute her for manslaughter.

Perhaps sensing that this was a difficult prosecution, the Attorney addressed the jury on criminal responsibility and age. Up to the age of 7, no child was considered capable of committing a crime, and beyond 14, all children were considered capable. Between the ages of 7 and 14, criminal responsibility came down to a matter of individual disposition. The facts as aired at the committal would stand, and the jury would hear evidence as to Emily’s character and disposition from her teachers.

First, David Penfold was brought into Court to confirm that his little girl was aged 11, having been born on May 10, 1862.

Girls’ Headmistress Martha Berry deposed to knowing very little directly about the girl, who was under the care of her teachers.

Infants’ Headmistress Dora Harvison thought that Emily was inclined to be sly, but highly intelligent, and could not say the girl was quarrelsome.

Assistant Teacher Lucy Lalor thought that Emily was intelligent, peaceable, but inclined to lay the blame on others for any faults.

Assistant Teacher Ellen O’Flynn thought that Emily was like all the other children in her class. Quite bright, and able to keep up.

No-one could recall whether Emily had been wearing boots that day. Had she worn them, Dr Hobbs deposed, they may have caused the injury that inflamed Constance’s lungs.

At this point, the Attorney-General gave up. He could not prove that Emily was a bad child, prone to quarrelsome and violent behaviour, and formally offered no evidence. The jury returned a not guilty verdict on this basis.

Emily Penfold was free to go home to her family for the first time in nine weeks. She was the most famous little girl in the Colony – the case had been covered at length in all of the newspapers. Some believed she was a poor child made to suffer at the hands of the legal system for something that could not even be proved. Others felt that she was a horrible little girl who had kicked Madame Mallalieu’s daughter so hard that she died.

The Penfolds, understandably anxious to start life over somewhere else, moved to Sydney.

Emily married William Baxter on Christmas Eve, 1883. She was later granted a divorce from Baxter on the grounds of his drunkenness and cruelty towards her. Having faced the Supreme Court at the age of 11, she faced it again in 1899 to end her marriage.

Emily remarried in 1900, to William Hickey at Redfern in Sydney. She died there on 13 June 1949.

SOURCES:

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Wednesday 25 June 1873, page 2

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Tuesday 24 June 1873, page 2

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Thursday 26 June 1873, page 2

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Friday 27 June 1873, page 2

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Saturday 28 June 1873, page 4

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 2 September 1873, page 3

Photo of Emily: Ancestry.com Public Member Photos

Children playing: Alamy stock photos

NSW Police Gazettes, 1879

Betty Crouchley, ‘Willmore, Henrietta (1842–1938)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1990.