Two men were executed at Brisbane Gaol on 12 November 1888. They were both foreign-born men trying to make a living in far north Queensland at the time of the northern gold rush. Both had become killers.

Edmund Duhamel, a Frenchman working in the gold mine at Croydon, killed his young de facto wife and tried to kill himself immediately after. Jealousy was his stated motive.

Sedin, a young Javanese sailor, had “run amuck” in Normanton, killing three men – he maintained right up to his death that he had killed the two in self-defence, but claimed no knowledge of the third. Sedin’s actions were blamed for a ferocious riot by the Europeans in Normanton, after which the Malays and other non-Europeans were taken out of town to a hulk in the river for their own safety, and then on to Thursday Island. Wild stories appeared in the papers of a blood-sacrifice ritual, multiple dark-skinned assassins and police inaction. Questions were asked in State Parliament.

The Killings

On 14 June 1888, two men sharing a tent between the town lagoon and the Norman River were stabbed to death. They were Christian Mariager and John Fitzgerald. Another man, J.P. Davis, was found the following morning, also stabbed. The crime took place at about 10:30 pm, and a 24-year-old Javanese man named Sedin was arrested at about 11:00 pm the same night.

The Europeans’ tents were set up close to a similar camp occupied by Malays, and it is from that camp that Sedin came armed with a knife and a Malay short sword named a Kris and killed the two men. (Although Java is part of modern Indonesia, the term Malay seemed to be a catch-all phrase in the 19th century.) The initial report of the crime, telegraphed from the sergeant at Normanton to the Commissioner of Police in Brisbane, stated that Sedin had been drinking and quarrelled with other Malay men. He was said to have armed himself and killed Mariager and Fitzgerald without provocation.

The Town

First inhabited by the Kurtijar people, Normanton is a port and a cattle town located in the Gulf of Carpentaria, closer to Papua New Guinea and Indonesia than its State capital Brisbane (see map). It was settled by Europeans in the 1860s, after being located as a potential site for a town by William Henry Norman’s party, who were searching for the lost explorers Burke and Wills. The discovery of gold nearby brought in people from surrounding countries, hoping to make their fortunes.

The remoteness of the town, and the rush of new inhabitants jostling for opportunities, created tensions between the comparatively recent white settlers and the south-east Asian people who worked as servants or ran small businesses.

The Riots

On June 16, the new-fangled electric telegram brought news to Brisbane of “great excitement” in Normanton the night before. A town meeting had been called by the Europeans, and a resolution were passed to call on the Government to expel all aliens in the Colony forthwith. The Kurtijar people, who were not consulted, kept to themselves any opinions they had as to who they thought were undesirable aliens.

Some Chinese “and other coloured men” had attended the meeting to discuss the situation, but were seized and thrown out on the street, abuse ringing in their ears. There was a belief that Sedin had not acted alone, and other murderers might still be lurking in the Malay quarter of town. Lynching was brought up as a possibility, but thankfully dismissed. The Europeans (male and surprisingly sober) marched to the Police office and confronted the Police-Magistrate and Sergeant Ferguson for a failure to control the alien camps.

Two hundred men then assembled at the river bank and were supplied with ropes and tarred firesticks (by whom, one wonders – someone already well-prepared for a riot?), and they went through the town, burning eighteen houses, torching boats and fishing equipment and destroying businesses. Their victims escaped with their lives and nothing else.

The following morning, the Police-Magistrate swore in forty Special Constables to try and impose order, and those run out of their homes were placed on board the Rapido hulk, and eventually taken to Thursday Island. The Chinese in Normanton were beginning to feel the wrath of the Europeans but had not been burned out or evacuated.

The following telegram has been received by the Colonial Secretary from the Police-Magistrate at Normanton: “Town fairly quiet on Tuesday. Have 60 coloured men of all nations on Rapido hulk, many of them quiet, respectable men. Am keeping them there for their own safety and to await steamer. Trust there will be no more riot but can offer no definite opinion under the circumstances.” Week (Brisbane, Qld.: 1876 – 1934), Saturday 23 June 1888, page 14.

The following week, Sedin was committed for trial for the murders of Mariager and Fitzgerald. He would take his trial at the Supreme Court in October.

“Premediated Murder”.

On 10 July 1888, a sensational article appeared in the Telegraph newspaper in Brisbane, quoting the views of a Mr Frank Gerald, who arrived in Normanton at the time of the riots. “Premeditated Murder” reported that a festival called “The Malay Christmas” was held on 14 June, and part of the conclusion of the festival was a blood sacrifice. Normally, Mr Gerald opined, this would be the blood of a sheep or a goat, but that night, the Malays decided on a human sacrifice, and Sedin was the man chosen to do the deed. Sedin was caught, but Gerald claimed nine other Malay men – possibly co-offenders – slipped out of the town before the rioting began.

Mr Gerald dismissed reports sent to Brisbane by the authorities as entirely inaccurate. He increased the rioter numbers from the Police-Magistrate’s estimate of two hundred men to five hundred and included dramatic stories of white men burning the very laundries where their shirts were being cleaned. So great was their passion that they would not spare their spare shirts, apparently.

No doubt the fearful tales of Malay blood sacrifice, retold in other newspapers, stirred fear and resentment of “aliens” in the hearts of their mostly white middle-class readers.

“The Norman Chronicle, in referring to their (the Malays’) departure says: -” All is well that ends well. Wisdom is once more justified of her children. The black agony is purged away from Normanton for ever. Will other towns follow such an example? We think it very probable. We cannot bring the dead, alas! back to life, but the dark clouds have a silver lining. The blood of the three martyrs has wiped out a foul stain, polluting the very springs and sources of our National life. A public monument should commemorate their melancholy death, and such a memorable sweep as has been made of the Malays.” quoted in Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Wednesday 25 July 1888, page 5.

Sedin’s evidence at the committal hearing was reprinted in the same edition as the quote from the Norman Chronicle, and it is hard to follow because it is rambling and in broken English – presumably any possible interpreter or translator was on a boat to Thursday Island. It details a bitter disagreement with two Malay housemates, some drinking, then an angry confrontation at the white men’s tents, which is where Sedin believed his housemates to be. Sedin, armed with a knife and a Kris, argued with the white men, who called him a blackfellow. Sedin threatened to stab the men if they called him a blackfellow again, they did, and Sedin killed them both by stabbing them.

Meanwhile, several men had been arrested for rioting, further angering the people of the town. A telegram was sent to the Premier, protesting the selection of the men charged – it would only be fair if three-quarters of the town was prosecuted, it said, otherwise this small group of men would be made martyrs.

Questions in the House.

At this point, State Parliament took notice. Not so much of the rioting, stories of blood sacrifice or even the murders as such, but of the issue of whether to compensate the refugees on Thursday Island. The House was not of the opinion that the displaced people were eligible for compensation, but some speakers raised a few points about the riots. Mr Morehead wondered how the European residents of Normanton might have felt had the situation been reversed, and they were forcibly removed from their homes. Sir T. McIlwraith said that the general population of Normanton had not been in “the slightest danger,” and asked whether the whole population of Queensland should have their reputation damaged by a disgraceful act against an “alien race”. The whole issue was then dropped.

Trial and Execution.

On 16 October, the Supreme Court, Justice Cooper presiding, heard the cases of Sedin, Duhamel and several of the Normanton rioters. Sedin and Duhamel were found guilty and sentenced to death, and no true bill was found against the rioters after the first case – that of James O’Brien – returned a verdict of not guilty. Cheering erupted from the public gallery of the courtroom at this.

The steamer Kurthi arrived in Brisbane with Sedin and Duhamel on board on October 28. They were quickly moved to Boggo Road Gaol to await a clemency decision by the Executive Council, and if that failed, execution.

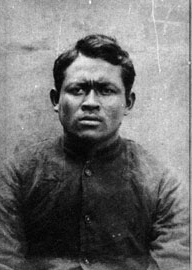

Sedin, November 1, 1888

One week later, the Executive Council decided to let the law take its course for both men, and they were executed on November 12, 1888. The Telegraph took information from a prison visitor with a rather more sympathetic view of Sedin.

The story is told in the condescending tones that 19th century European journalists used to describe people of different races or ethnicities, even ones they claim to approve of. The subjects are described as “pleasant/fine looking”, “a fine example/specimen of his race “or “quite/remarkably intelligent.”

The Malay’s Confession.

A gentleman, who has had the opportunity of conversing with the unfortunate men, has described Sedin as a pleasant-looking young man of about 25 years of age. In answer to questions the convict said that he was conscious of having killed two of the men, but he had no knowledge of the death of the third man. He manifested no regret at the commission of the deed, because it was done purely in self-defence. He emphatically admitted that it was cowardly and wrong to take innocent life, but in accordance with the teachings of the Mohometan religion he could not apparently see any wrong in taking life in self-defence. His own version of the affair for which he has suffered the last dread penalty of the law is in effect, as follows:

He went to Normanton from the diving grounds, in possession of about £200, and having purchased a horse and dray settled down to work in that town and was in a fair way of doing very well. Being an alien he with others was continually the subject of rough treatment at the hands of the Europeans. Things went on in that way until the morning of the tragedy, which aroused the bitter animosity of the whole white population of Normanton.

On that morning Sedin was accosted by a man who abused him in unmeasured terms. Now the Mahometan religion teaches its believers not to lie, nor swear, nor drink, and to their credit be it said as a rule they resolutely abide by its teachings. When this man used bad language to the Malay, he assured his abuser that if he did not desist, he would die. There upon the man seized a block of wood and assailed Sedin. Immediately a second assailant produced a revolver, but before the Malay could be placed hors de combat he had stabbed his first assailant twice and the second also. To use Sedin’s own words, ‘ Me kill ’em quick.’

What followed is a matter of history — the whole of the Malay population was routed out of the town and placed on board a vessel near the Norman River, and thence subsequently transferred to Thursday Island. When asked whether he was ready to die, Sedin replied, ‘ I no fear death; I fear Allah.’ He declined the ministrations of a clergyman on the ground that he believed in his own faith and produced a book— part prayer book and part hymnal — from which he chanted several portions, in a plaintive sort of dirge. Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Monday 12 November 1888, page 5.

Sedin did seek a little last spiritual comfort from visiting chaplain Mr McPherson just before his execution. Nobody was sending a Muslim cleric to help him through his last days.

He would need all the strength he could get. His execution was a horror. Duhamel died instantly just before him, and, having had to witness that, Sedin was taken to the scaffold. The executioner initially removed Sedin’s turban to put the white cap on him, but Sedin protested, and the gaoler spoke up and made the man place it back on the prisoner. The Chief Warden also allowed Sedin as much time as he needed with the Koran and to say his prayers. The witnesses described his devotions again as a “dirge like chant”.

The prisoner took 14 minutes to die of strangulation. The Brisbane Courier the following day, raised questions of the slow cruelty of the execution of Sedin, pondered the question of capital punishment in the light of the wonderful electric machines used so humanely in America, then concluded that in future, executions should be carried out by “more skilful hands”.

There were no more riots, and today Normanton is peaceful and diverse, with that beautiful wide-street, pub-with-veranda style of the North. More than half the population is indigenous, hopefully many of them descended from the Kurtijar people.

SOURCES:

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Saturday 16 June 1888, page 4

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Monday 18 June 1888, page 5

Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld.: 1866 – 1939), Saturday 23 June 1888, page 982

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 11 July 1888, page 6

Week (Brisbane, Qld.: 1876 – 1934), Saturday 23 June 1888, page 14

Queensland State Archives Series ID 10836, Photographic Records, Descriptions and Criminal Histories of Prisoners Executed

Western Star and Roma Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1875 – 1948), Saturday 30 June 1888, page 2

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Tuesday 10 July 1888, page 5

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Friday 20 July 1888, page 5

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Wednesday 25 July 1888, page 5

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Saturday 4 August 1888, page 6

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 19 September 1888, page 6

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Friday 12 October 1888, page 5

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Tuesday 16 October 1888, page 5

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Wednesday 17 October 1888, page 5

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 17 October 1888, page 5

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Tuesday 30 October 1888, page 5

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Thursday 1 November 1888, page 4

Mackay Mercury (Qld.: 1887 – 1905), Saturday 10 November 1888, page 2

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Monday 12 November 1888, page 5

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 13 November 1888, page 4

Bank of New South Wales and Burns Philp Building photos: http://www.aussietowns.com.au

Map: Whereis.com