In the 1890, the fifty-fourth year of Queen Victoria’s reign, the Legislative Assembly of the Colony of Queensland passed the Married Women’s Property Act. Similar legislation had already been enacted in the United Kingdom and other Australian Colonies.

Prior to this Act, married women did not have the kind of property rights as single women, regardless of whether they were earning the larger share of the family income or had owned valuable property outright prior to the marriage.

It was considered shocking and revolutionary at the time, not least by men who stood to lose from it. Men like Robert George Woodward.

The Act at s. 15 provided:

A spirited widow would use the Act to protect herself and her property against Mr Woodward in later life. She paid a great personal price.

Robert Woodward was a native of Hertfordshire, he married Ann Hipathite there, and they set about having a large family – twelve children, nine of whom lived to adulthood. The Woodward family emigrated en masse to Queensland Australia in 1874, where Robert hoped to make a life as a farmer in Samsonvale. Things weren’t easy, but they weren’t too bad, compared to the fortunes of other emigrants in these pages.

In 1891, Ann Woodward died aged 57, and things went downhill. By this time, all of Robert’s children had grown up and had moved away, and none wanted the trying job of looking after (putting up with) Dad and his temper.

Unable or unwilling to live as an aging widower, Woodward married a widowed storekeeper of 30 named Emily (Owens) Emmerson on 23 January 1892. She had property and money of her own, and if she was a bit plain (the newspapers would describe her as a heavy-featured woman), it was nothing he couldn’t put up with. She could manage a household, possibly even help manage a farm.

The marriage was miserable from the start. Emily claimed Robert beat her three weeks after they were married. He sold a property that was hers, to try and purchase a selection of land. They argued. She left after several months, and, using her first husband’s surname, sought employment at stations and in small towns west of the Darling Downs.

Robert Woodward did not take this desertion lightly. He tracked his estranged wife about Queensland – no easy task in remote places in the pre-internet era – threatened her and jeopardised her employment by contacting prospective employers with false bad references about her. On 01 November 1892, Emily was in Brisbane and went to the Police Magistrate to apply for a Property Protection Order. She gave evidence and an order was granted. She hoped it would protect her.

Armed with her order, Emily again went west and spent nine months at Beranda Station as head nurse, and when that situation ended, bought a ticket for Toowoomba, but decided to stop at Roma. She moved to the Commercial Hotel at Roma, where she boarded for a short time, looking for another job at a station.

Early on 11 October 1894, the indefatigable Robert Woodward arrived in Roma on the Brisbane mail train. He knew his wife had been at Beranda Station and had bought a ticket for Toowoomba. He knew that she hadn’t arrived there and discovered that she was staying in Roma. He believed she was consorting with other men. Armed and furious, he went directly to the Commercial Hotel and made his presence known to Emily in the dining room.

Emily asked what he wanted, and he replied, “Breakfast.” She went to the kitchen with a serving girl while Woodward ate his breakfast. She was afraid to be alone with Robert. Woodward came into the kitchen and demanded to speak with her. Her evidence stated:

‘I was assisting the girl to wash the dishes when the accused came in and asked me to go to Brisbane with him. I answered, “What is the good of you wanting me to go home when you sold the house over my head”. It was a bogus sale. He said, “If you don’t come home with me you won’t go with anyone else; I will do for you.”

I was afraid to be alone with him and went to the dining room. He still bothered me and promised not to beat me. I told him that I had given him trial enough. He was a widower when I married him with four sons and five daughters, four of whom were married. His children would not live with him. Accused began to get angry, and I said I would give him in charge. He said, “if you do you will not get the chance again, I will shoot you.” I went and got the protection order from the bedroom. I felt in danger and told the girl so, who said “There is a man; get him to bring a constable,” but I was afraid as accused was following me. I could not get away. I look round and saw accused. I remember nothing more until finding myself in bed wounded.’

Robert Woodward had shot her in the head. The bullet entered the jaw on the right side and exited near her left ear. She came close to bleeding to death, and might have died had not Dr L’Estrange, the Government Medical Officer at Roma, been close by. Everyone thought the wound would kill her, and her recovery was miraculous.

While help was being arranged, Robert Woodward went to the bar and demanded to be arrested because he had shot his wife. He was not initially believed, so he strode around outside. John Bourke asked what was going on:

‘Accused said, rather excitedly, “I’ve done it.” Witness asked, “Done what?” Accused replied, ” Shot my wife.” Witness said, “What for?” –Woodward replied, “Because she would not come home.”’

The proprietor of the Hotel, Bourke and Dr. L’Estrange tried to convince Woodward to hand over his gun. He refused to give it to anyone but a constable. He demanded again to be arrested, and Dr. L’Estrange pulled rank as a Magistrate, and ordered Woodward to give over the gun. Woodward complied.

Robert Woodward was committed to take trial for attempted murder at the February 1894 sittings of the circuit court. Emily Woodward was able to attend the committal hearing and give evidence. Woodward never denied shooting her.

The trial was largely a replay of the committal hearing – the Crown read all the evidence against Robert Woodward, but this time, he had an opportunity to give evidence. Stubborn as ever, he had represented himself, and gave what was described as a “rambling” account of marital arguments. Woodward believed that by taking out protection under the Act, and by leaving him, Emily had caused him to lose a selection of land.

The prosecutor, in cross-examination, asked plainly if he had shot his wife. He replied yes. That was it – the jury was out for ten minutes and returned a guilty verdict. Justice Real addressed Woodward:

‘You have been convicted on the clearest possible evidence, but though the jury have taken a most merciful view of the case — that you did not want to kill your wife— so far as the sentence is concerned it makes no earthly difference. On either charge you are liable to a sentence of penal servitude for life, or for a period not less than three years. But the difficulty I have in dealing with you is that you show yourself so excitable that I do not know how long it will take for your blood to cool down, and to give you anything like a light sentence would seem very like encouraging murder. The same spirit which actuated you in coming here might still have control over you. I will not give you a very severe sentence, as you are an old man; still, it will not be a light one, and will, I hope, afford time to allow your better judgment to have the ascendancy. The sentence of the court is that you be kept in penal servitude for a period of five years.’

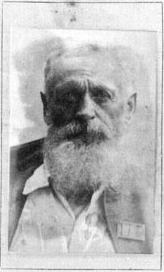

Robert Woodward served some of the sentence on St. Helena Island in Moreton Bay. He looked mightily ticked off in his prison photo. He died aged 67 in 1899 in Brisbane Hospital under the care of Dr. James Mayne (son of the infamous “Mayne Inheritance” Patrick).

Emily Woodward returned to Samsonvale, and lived uneventfully, except for a tragic incident where she and a neighbour helped a distraught young woman in premature labour, and the baby died shortly after the birth. She died in 1919.

Sources:

54 Vic (1890) Married Women’s Property Act

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Thursday 12 October 1893, page 4

Western Star and Roma Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld. : 1875 – 1948), Saturday 14 October 1893, page 2

Western Star and Roma Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld. : 1875 – 1948), Saturday 14 October 1893, page 2

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Thursday 22 February 1894, page 5

Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 – 1939), Saturday 24 February 1894, page 341

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Wednesday 23 August 1899, page 3

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Friday 16 February 1906, page 3

Photo: State Archives of Queensland.