ANOTHER TASTE OF THE CAT-O-NINE TAILS – LIFE IN MISERY – DEATH IN PREFERENCE.

As soon as I had been ” told off” properly, I was put into the “chain gang.” I was ironed very heavily; the weight I should fancy of my Moreton Bay ornaments being about 16 lbs. I was sent to work falling and clearing, and the first lesson I had of the management in my new quarters did not increase my love for the rustic retreat.

I was working by the side of a fellow prisoner named McCarthy, and I do believe he was ill, and unable to work; he was told to go on with his work by the overseer, and he said he was not able. The overseer reported McCarthy to the Commandant as a man who would not work, and he was ordered to receive one hundred lashes.

How that poor wretch groaned-how tightly they gave it to him! When he was cast off, he was told to go to his work the next morning, and if he did not work, how they would flog him again.

The next morning found McCarthy in the gang, and he could not work. The overseer said he was able so to do, so they flogged him again, giving him another hundred. How glibly one can say, “one hundred lashes.” They were not comfortable to take I can assure you. Well-poor McCarthy said also on the third day, he was not able to work; and they gave him, while he shrieked for mercy, another hundred, making three hundred in three days.

I believed McCarthy was ill-believe so now, and shall do so, even if all the doctors who were in the Government establishments signed certificates to the contrary. They flayed his back until it was one mass of wounds. His spirit was broken. Life was despised. At that period no one knew any-thing of the back country. To go into the bush was to go to death, and yet McCarthy went, having by some means obtained release from his irons. I hear his agonized wail now-see him in fancy, as he came the last time to the gang, heard, and knew he was missed-that be had taken to the bush, feel satisfied he must have perished; and I may add, he has not since been heard of.

This little incident taught me I had come to a spot where They were not very particular how they kept the spirits in subjection, – and I hoped by hard work and attention yet to be, extricated from my misery. This kind of feeling would be succeeded by despondency, and when I hoped I had calmed down the tumult effectually, liberty and the thoughts of I know who, would make me say, ” irreparable is the loss; and patience says, it is past her cure.” I have no right to tell other than my own sufferings for my own sins, far less to moralize, but in the recital of such a life as mine, I pray you par-don me if I tell of a few of the sufferings of others.

A man who came down to Moreton Bay at the same time that I did, was punished with 100 lashes; and to increase his torture he was fastened to a fence so that the mosquitoes might increase his punishment. I forget his name, but had I known the free people would ever have taken an interest in reading the sufferings of criminals, I might Have been more particular in jotting down the incidents which daily came under my notice.

I had been in Moreton Bay some few months, when a fellow prisoner, whose name was Winter, agreed to run away with me. We cut the heavy irons through with an old knife, started at the first opportunity, reached as far as Point Danger, where we were re-taken by the soldiers, sent up to Eagle Farm, and the morning after arrival marched to the settlement for punishment. We were each given 100 lashes, and the weight of my irons was increased to 24 lbs. The next morning found me in the gaol gang, in which state of disgrace I continued about a month. Being, as I have stated previously, a favourite for my working qualities, at the end of that time I was sent as driver to a bullock team to cart some cedar for a vessel which Captain Logan was at that time getting built. I kept my quiet and continued to drive the team, until an act of villainy on the part of a fellow named Chaffey, brought myself and eight others into disgrace and punishment.

This fellow Chaffey was plotting to get his liberty, and as telling tales was a prevalent manner of scraping favour, he, with devilish plausibility, invented how I and eight others were going into the bush. There was no truth in his story. That did not matter; we were brought up, tried, and each was paid to the tune of 100 vile blows with the ” cat-o’-nine-tails,” which was equal to 900 lashes from a single thong. I make this re-mark in order that the severity of the flog gings which I have to record may be better understood. We were all innocent of the alleged crime. One poor follow, when smarting from the violence of the lash, gave vent to his innocence –

” There’s a hundred for doing nothing,” he groaned.

The Commandant immediately said, “I’ll give you fifty more for doing something;” and he did according to his word.

Oh Lord! my back had been cut and chopped, until it was scarcely ever well. The fire used to flash from my eyes while I was taking the floggings, and it seemed as if the very hell of agony had fastened on me. A boiling sensation of pain, as if I was being scorched with a red hot iron was the sensation towards the close, and sometimes I thought I must have shouted for mercy ; the devil of determined doggedness had taken possession, and I held my pains to myself, so that I was, looked upon as ” a brick” that ” tanning” could not tame in the desire to be free.

The ” gaol-gang” was my dislike. I didn’t like the extra heavy irons, nor the way we were chained of a night all together. It would have given us a tough job to have cut that large chain, which encircled us all in our misery. I wish I could remember distinctly many circumstances of interest, but as I am growing old, and did not keep an account of ought save my trials for liber-ty, I can only speak of a few incidents which were of such a character as to fasten themselves on the memory of the most obtuse.

One day I was at work with another man with a sand-cart, a soldier behind us, when my mate, finding one of his leg-irons slipping on to his heel, put down his hand and stooped to lift it. The soldier, without a word of warning, plunged his bayonet into the poor wretch’s back, saying, as he did it, ” go on you b——.” I kept on with my work; but turning my eyes, I saw my comrade down. Poor fellow, it was his death-stroke. They did say the bayonet entered his kidneys. At all events, he died in three days, and there was no more about it. This scene was enacted near to the Old Waterhole. I grew tired of life, and so did others. Working one day on the line of road, which was then being constructed, there was a prisoner named Tom Allen, and a Scotch, boy by his side, I call the last named a boy, he was so young, though he had apparently grown up. I give the scene exactly as it occurred.

” I am tired of my life,” said Tom Allen. ” So am I,” answered the boy. ” I will kill you if you like,” responded Tom, ” then they will hang me, and there will be an end to both of us “

” Do so,” spoke the boy.

Tom raised the pick he was using, struck the boy on the head, from the effects of which blow he fell. Tom drew the pick from the head of the boy, placed his foot upon the head, and dealt another blow-the boy’s life had gone. As Tom finished his bloody deed, he exclaimed, ” So, now we are both dead men.”

Tom Allen was taken to Sydney. After the formulas of the law had been observed, as much as they used to be in those days, he was hanged. He sought to lose his life, and they rewarded him the way he wished.

A convict was engaged in hoeing. He rose upright, waited for a moment, then leaned on the implement he had been working with, and seemed meditating. Perhaps he was thinking of some green spot in his existence, when the irons had not encircled his limbs, before crime had scorched his heart. I know, by myself, there are some such moments in the flitting light of depravity, when good beckons to purity, and puts to flight a legion of evil desires.

“Go on with your work,” halloed the overseer.

The convict remained fixed in his meditative attitude.

” Go on with your work.” No response-no motion. ” Go on with your work.”

The convict stood still and silent.

The overseer went towards him, struck him with a stick a very heavy blow on the back of the head, the man fell; the blow had killed him. They wrapped him in soogee bags, took him away to the hospital, and I don’t think there was any inquiry about it.

I had in the meantime managed to get out of the gaol gang, but for some fault or other, found myself in it again. Nine of us were in together in a mess, and one dinner time we made up our minds to try to get out. With an old knife the rivets were cut; all was ready for action; the bars of the window were also cut, and hope was high. The signal went round, we began our work, some had passed through the open space, and the others were waiting to follow, when the alarm was given. All were taken save one Jack Ellis, who eluded the search, passing up a drain, but he was discovered and hauled out the next day. The usual 100 were given to all who had been concerned in this futile attempt. To tell of the cruel blows would only be a repetition of what I have already narrated; oh what will not the slave dare for liberty?

Gaol-gang again, more heavily ironed than before, with a regular runaway character -such was my lot, and I thought as well as I could, if it would not be better to “give up,” than keep failing and receiving punishment. This train of reflection only lasted a short period, before ” liberty” tempted me again to dare.

There was in the gang I was in at this time one Charley Boggs. Captain Cluney (Clunie) was the Commandant -but no matter who commanded, we felt we were slaves. While engaged at work I muttered to myself, ” I’ll reach Sydney, if I live, so that I can get out of the country.” Charley was spoken to by me on the subject, he entered into the plan with zest, and the next day we deserted, taking with us an axe, a little flour and some rice. We jogged along very comfortably, considering our short fare and the difficulties, until we reached Point Danger. I could not swim-there were no other means of crossing that I could then imagine, so Charley swam across and left me. I tried to follow the best way I could, lost the axe and some other little trifles in the water, so was fain to content myself on the side where I fancied the greatest danger existed. Charley went on his way, leaving me to do the best I could. I thought it precious hard at the time, that he should desert his chum, and accused him, to myself, of not being a true fellow. Had I been able to swim as he did, and he not able to cross, I might have left my companion, for they were times in which no one was very particular, the bayonet and the lash seeming to goad on the forsaking of all to save one’s-self.

For three days was I on this side of the water, vainly trying to cross, and I had begun to think of dying, when a party of blacks made their appearance. I expected to be used roughly. I told them my story and related what I had lost in the water. These hospitable blacks got my kettle, my trousers, an old knife and the axe from the water; gave all to me save the axe, which they kept, and took me to a place where I was enabled to cross by some contrivance which they had previously arranged for their own convenience. Once more on the way I steered again for the coast, where I fell in with two gins who gave me some cockles and oysters, in the strength of which I pursued my journey. I began to feel the effects of travel and hunger, when near the Richmond. About a mile from this river ” I fell in with a kangaroo,” which I carried to a deserted camp, and some fire being found in a hollow log, I roasted my prize, and soon was forgetful of the troubles I had experienced and the dangers still before me.

The next morning. I awoke refreshed, and gazed upon the Richmond. I had gathered experience from the delay at Point Danger, so set to work to make a raft. When I had completed my great operation, I launched the fragile construction into the water, and not being sufficiently careful, the tide carried it away before I could commit myself to its tender keeping, ” Don’t give it up,” I said, for I had a way of talking out to myself, for want, so long in my life, of having anybody else to talk to. I made another; was more successful in the launching, ventured on it, and after many narrow escapes from drowning, arrived safely on the opposite shore.

I travelled on, nothing to cheer me save liberty, until sometime that day when I hit upon Bogg’s tracks. I began to be in luck and followed them as sharply as if I had been a red Indian on a war trail. I was worse, I was on the trail of liberty or death; for I expected, if ever I was retaken, that the punishment would be strangulation with a hempen halter. The thought every now and then quickened my steps, until my wary sense told me not to hurry too much, or I should never reach the place I sought. For three days did I travel on, cheered by the tracks, till good fortune threw in my way nine young emus, which I killed and carried on with me, so that I might not die of hunger. At the close of the third day I was near the Clarence, darkness had come on and I, finding some deserted huts, began to prepare for my night’s repose. I had no fire and began to fancy I should have to eat some of my emus uncooked, when, lying on the ground, a little distance from me, I saw a spark of light. I stood upright and looked but was unable to see it in that position. Fancy was rife. I wondered what it could be! I resumed my old position, saw it again, and crawling on my hands and knees towards the spot found, to my great joy, that it was a small coal of fire, a long way up a hollow log; which log must have been burning for a long time.

I tore a piece of the old and dirty shirt I wore and fixing it in the end of a long stick which I obtained, put it up to the fire; and having waited some little time in endeavouring to get it light, was at last successful, and began to make a fire. The crackling sticks began to give to the fire power, and when the stream of light shot up, I heard a moaning noise. I said, half afraid, ” Who’s there?” There was no answer, but the moan again. ” Holloa”-moan again. At last I shouted, “is that you Charley?” A faint “yes,” made my heart leap. I was no longer alone in the world. Calling out of the depths of past experience, though years had gone by since I heard the only voice of welcome for which I had a blissful response, and though the voice that gave the feeble “yes,” was the voice of him who had left me to my fate at Point Danger, I felt for a time happy. The greater overshadows the less. Companions in distress can sympathize truly, and only humanity that has suffered even as he and I had done, can know how lightly I tripped to the hut wherein he was, in hopes of going along the ” way of difficulty” together. My hopes and rejoicings nearly went down to zero, when I learned his state.

The descriptions and names seemed familiar, and a little detective work showed the tale to be almost entirely true.

There were several prisoners named McCarthy at Moreton Bay, but none absconded. A John McCartney (prisoner #20) arrived at Moreton Bay on 22 March 1826, and absconded on 15 June 1826, never to be heard from again.

Thomas Allen (prisoner #1170) was charged, convicted and hanged for the murder of 21 year old John Carroll in February 1829. He did not act alone though – Thomas Mathews also participated in the murder and was punished for it. The conversation and location of the murder suggests Patrick Maguire (prisoner #2383), who killed 17 year old Matthew Gallagher (prisoner #1790) on 06 January 1832 at the gravel pit, telling the soldier who went to arrest him that he was “weary of his life and wished to die”.

Robert Winter (prisoner #866) a groom from Yorkshire born in 1794, was a lifer transported in 1812. He reoffended in November 1826 by committing a burglary and received 7 years at Moreton Bay. He absconded on 16 December 1827 and returned on 19 January 1828. It was his only recorded escape. He finished his sentence and returned to Sydney on 13 February 1834.

William Chaffey alias George Chaffey (prisoner #523) was born in New South Wales around 1803 and had been sent to Moreton Bay for Cattle Stealing in 1827 for a term of 14 years. He did not return to Sydney until well into the next decade.

Charles Bogg (Prisoner #1358) a native of New South Wales, was sentenced on 01 March 1828 to 7 years at Moreton Bay for Privately Stealing in a House. He absconded on 07 July 1829, returning on 02 May 1830, then absconded again on 11 April 1831. When recaptured he was sentenced to Norfolk Island.

John “Jack” Ellis (prisoner #1565) was an Irish Soldier and Labourer, who was transported in 1826 for desertion, and then sent to Moreton Bay in 1828 for “Divers Highway Robberies”. Ellis absconded so frequently that he managed to turn a 3-year sentence into 5 by running away twice in 1829, and once each year thereafter. Practice made nearly perfect though – he managed to learn from his experiences, going from 3-day jaunts in his early days to 6 months in 1832. He was at last returned to Sydney on 04 February 1832. There must have been sighs of relief from the captors and their captive.

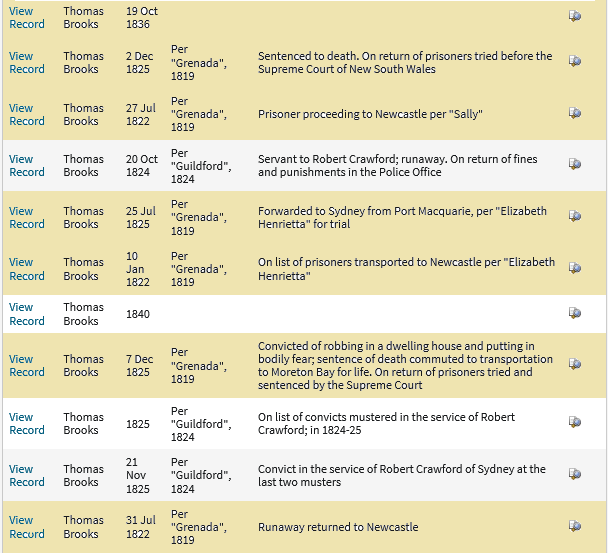

And Jack Bushman? I believe him to be Thomas Brooks (prisoner #18). He was 33 at the time he was sent to Moreton Bay, and was originally was transported on the Grenada 1 in 1818. Some details have been changed, but look at the Grenada Mr Brooks’ record in the Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence:

The 1836 entry is the commutation of the life sentence on the recommendation of Captain Foster Fyans (see part 3). Even the commuted death sentence rings true. Brooks eventually received a conditional pardon in 1852.

Part 3 of Jack Bushman’s Tale to come….

Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 16 April 1859, page 4

New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence.