In 1830, a Sydney newspaper named The Monitor published a series of articles alleging that the Commandant of the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement was a bloodthirsty tyrant, and possibly a murderer. That Commandant, Captain Patrick Logan of the 57th Regiment, had prepared to sue Hall for libel, when his own murder intervened.

What led to the Monitor’s Editor, an Englishman named Edward Smith Hall – already in prison as a result of other libel cases – to risk further litigation, and indeed more gaol time, to write such scathing articles about a public figure?

The causes are complex, but can be traced to September 1826, when two were arrested, charged and found guilty of shoplifting, and then all hell broke loose.

Sudds and Thompson

Privates Joseph Sudds and Patrick Thompson were stationed in Sydney with their Regiment, His Majesty’s 57th Regiment of Foot, the original die-hards. (Colonel Inglis, rallying his men, cried: “Die hard the 57th, die hard!” at the Battle of Albuera in 1811. It may be the origin of the phrase.)

In 1824, the Regiment had arrived in Sydney bearing banners of their glorious campaigns in the Napoleonic, Peninsular and American wars. At the same time, a new Governor of the Colony, one General Ralph Darling, took charge of the Colony. An autocratic leader, skilled in the setting up of infrastructure, he did not suffer fools, or critical newspapermen, gladly.

In 1826, a detachment of the 57th Regiment went to Moreton Bay penal settlement under the command of an able (but again, autocratic) Scottish captain named Patrick Logan. The rest of the Regiment was stationed and worked in Sydney.

In November 1826, Joseph Sudds and Patrick Thompson appeared at the Sydney Quarter Sessions, charged with stealing from the shop of a Mr. Napthali. They had selected calico to purchase, Sudds walked out and left Thompson to pay, whereupon Thompson began abusing the shopkeeper, refused to pay and followed Sudds. The two men were caught with 12 yards of calico on them. The Bench found them guilty and sentenced each of them to seven years’ transportation to a penal colony.

The press report remarked that, “The prisoners appeared to be most daring characters. On sentence being pronounced, Thompson enquired of the Chairman if he would send his firelock with him to the penal settlement he talked of, as, in that case, he could go into the bush.”

What happened to the two men when they were taken into custody set off a chain of events with legal consequences that would trouble Governor Darling, the 57th Regiment, Edward Smith Hall and other newspaper editors, for the next decade.

General Order.

HEAD QUARTERS, SYDNEY, 2nd November 1826.

“The Lieutenant General, in Virtue of the Power with which he is vested as Governor in Chief, has thought fit to commute the Sentence, and to direct that Privates Joseph Sudds and Patrick Thompson shall be worked in Chains, on the Public Roads, for the Period of their Sentence—after which they will re-join their Corps. The Garrison has been assembled to witness the Degradation of these Men, from the honourable Station of Soldiers, to that of Felons doomed to labour in Chains.

It is ordered, that the Prisoners be immediately stripped of their Uniform, in Presence of the Troops, and be dressed in the Felons’ Clothing; that they be put in Chains, and delivered in Charge to the Overseers of the “Chain Gangs,” in Order to their being re- moved to the Interior, and worked on the Mountain Roads—being drummed, as Rogues, out of the Garrison. The Lieutenant General considers it unnecessary to enlarge upon the disgraceful Conduct of these Individuals. The ignominious Condition, in which they are now exhibited to their former Comrades, is the best Commentary on their Proceedings; and the total Failure of their Scheme will furnish a Lesson, should it be necessary, to warn others against any similar Attempt.”

The Sydney papers could not digest the sentence of transportation, which was supposed to be inflicted on reoffenders, not men who’d come free and were convicted of their first offence. For Darling to then “commute” the sentence to 7 years on a chain gang, when commutation of a sentence usually meant discharge from punishment or a lesser one (life imprisonment, rather than execution), had legal experts and pundits puzzling at inordinate length in editorials across the Colony. Small editorial scuffles commenced between the Gazette, The Herald, The Australian and The Monitor over the veracity of their sources.

Then Joseph Sudds died.

On 29 November 1826, a voluminous editorial in The Australian on the legality of the Governor’s exercise of his powers was urgently amended thus:

We had scarcely finished the foregoing remarks, the ink was hardly dry, when the following announcement reached our Office :— ” Sudds, the private of the 57 regiment, who was convicted of petty larceny—and sentenced to seven years transportation to a penal settlement; and who was after that sentence, publicly exposed on Wednesday last in a convict’s dress at the barracks, and drummed out of the regiment, (although at the time he was so ill as to be scarcely able to stand) DIED THIS MORNING! His comrade, Patrick Thomson, who appears almost in a state of fatuity, and who after his sentence by the Civil Law, underwent a similar military punishment, has ever since continued loaded with chains of such a nature and form as to prevent him from extending his body, and from lying on his back, belly, or side, when he would endeavour, to sleep.

The effect of the news of Sudds’ death in a small colony where everybody knew, or thought they knew, everyone else’s business was electrifying:

The whole town was in commotion. Business was partly at a stand-still—and the fate of the unfortunate man occupied every mouth from morning till night —it was in vain to think or talk of anything else—nothing but Sudds and Thomson, the death of the former and the alleged lunacy of the latter were to be heard of from the Battery to the Brick-fields, and from Cockle Bay to Hyde Park. At Parramatta it was just the same. At Liverpool there was also a considerable sensation on the Thursday.

In the absence of an inquiry into Sudds’ death, Editors began attacking each other in earnest – The Gazette railed against The Australian, The Monitor sided with the Australian, The Gazette turned its fury on the Monitor. A great deal of this turmoil was incited by the Letters pages, in which “A Subscriber” and “Quinque” purported to give an inside story of the death of Sudds, until Alexander McLeay, the Colonial Secretary, felt obliged to write to the Australian (Australian (Sydney, NSW: 1824 – 1848), Saturday 2 December 1826, page 2).

As December 1826 went on newer sensations began to occupy the press, and Thompson’s admission to hospital and transfer to the Hulks awaiting a journey to Moreton Bay was only noted in passing.

One editor continued worrying at the topic, Edward Smith Hall of The Monitor.

Edward Smith Hall (1786-1860), hailed from Lincolnshire and had devoted his early life to religious and charity work, impressing such prominent figures of the day as William Wilberforce and Sir Robert Peel, who encouraged Hall’s plan of emigrating to the Colonies to improve the tone of the place and spread charitable and Christian works.

Edward Smith Hall (1786-1860), hailed from Lincolnshire and had devoted his early life to religious and charity work, impressing such prominent figures of the day as William Wilberforce and Sir Robert Peel, who encouraged Hall’s plan of emigrating to the Colonies to improve the tone of the place and spread charitable and Christian works.

In 1811 Hall was granted an initial 700 acres which increased to 2380 acres by subsequent grants. Mr Hall had envisioned life as a gentleman farmer, and quickly became a pain in Lachlan Macquarie’s, er, neck. The Governor described Hall as a “Useless and discontented Free Gentleman Settler … without making the least attempt at Industry, expressed himself Much disappointed in Not getting his Land cleared and Cultivated for him, and a House built for him at the Expense of Government.” Still, Macquarie found, when Hall’s energies could be channelled from grumbling about his lot in life to socially useful activities, he was a useful man to have about the place.

Hall found his way into publishing in 1826, having exhausted the possibilities of banking (he quarrelled with his superiors), an appointment as Coroner and another go at farming. The Monitor was founded by Hall and Arthur Hill to give voice to the settlers and free men, but most particularly to have a red hot go at the high-handedness of one Governor Darling.

The Sudds and Thompson case provided Hall with just the ammunition with which to besiege the Governor, who retaliated by curtailing the grazing rights on Hall’s farm and then imposing a stamp duty on newspapers. Hall was in journalistic heaven until his pew at St James’ was assigned to another individual, and he wasn’t having any of that. Hall created a spectacle on Sunday 01 July 1828 by forcing his way into the pew and damaging the door (according to the Crown) or by being ejected, assaulted and humiliated by the beadles (according to Hall). Hall’s fury at this treatment, writ large in the pages of The Monitor, again attracted the attention of the Crown, and found himself in the Supreme Court, defending himself against trespass (upon the pew), libel (on Archdeacon Scott), and stamp duty breaches. The upshot of all of this was 12 months behind bars.

During Hall’s time in prison, Thompson was discharged to the Military from Moreton Bay Penal Settlement. Hall got hold of a story about Captain Logan threatening and humiliating Thompson, and Captain Logan became his new bete noir. The Monitor had shown no interest in Logan prior to the Thompson story, now the Horrors of Moreton Bay and the Cruel Commandant joined Archdeacon Scott, Governor Darling, the pew and stamp duty in his editorial tirades.

Thompson the surviving victim of the iron collar and novel chains, on being reprimanded and threatened by Captain Logan, at Moreton Bay, told the latter, he was no longer a soldier, that he had been drummed out of the service and would no longer serve; and accommodating the action to the word, he threw his cap at the Captain’s head! He is to be brought down to Sydney and tried by a Court martial. We suppose however, by a motion in the Supreme Court, the question of his liability to such a trial, will be mooted.

By October, Smith, scribbling furiously from goal had indeed placed all of the above characters in one long, steaming editorial, largely about Sudds and Thompson. He was forced to write in haste and discomfort, handing his work to a boy from his office to take to the printing press.

Now what was the conduct of His Excellency Lieutenant General Darling, on the death of private Sudds? No Inquest was held on the body. The Court Journal uttered its cruel insulting and scandalous aspersions towards a horror-struck people. Thompson was ordered still to wear the illegal and tormenting chains and was sent up to a gang the most renowned for severity and harsh treatment. There, under an almost vertical sun, the iron collar burnt his neck, so that he was fain to sit down on the stump of a felled tree and hold it with both his hands to keep it from scorching him and inducing the same disease, which in part killed private Sudds, viz. Bronchites. His cruel taskmaster, in the meantime threatened him with punishment because he neglected his work. But sufferings like these could not last long. Though fortified with a most robust constitution, the torment of his chains, coupled with a wounded spirit, arising from a sense of oppression, together with inferior and insufficient provisions, brought on him the dysentery. Fortunately, he survived the attack, though brought by it to death’s door. Surely now justice was satisfied? No. He was transported to Moreton Bay. There, being impressed with an opinion, that as his sentence had once been commuted to an iron-gang, such commutation could never be changed; learning this piece of law from the newspapers; he refused to work and went a hunting in the bush. For this he was severely scourged by Captain Logan twice. At length, after nearly three years, a free pardon was read to him. But it was a species of mockery; for as soon as read, the man, though he had been drummed out of the army under circumstances more ignominious than was ever recorded in our military annals, was compelled to enlist as it were a second time. But he would not go to drill. Hence for three months he was by Captain Logan put into the guardhouse at Moreton Bay. This is the line of conduct His Excellency judged it politic to pursue towards the survivor Thompson.

Hall could not help but take notice of the Moreton Bay murder trials taking place in Sydney at that time. Several prisoners had been murdered by their comrades, and conditions at the settlement began to come under his scrutiny. There were plenty of former prisoners of Moreton Bay who sought to tell their stories and found an interested audience in the editor of The Monitor.

Captain Logan

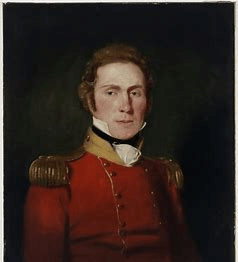

Hall’s grievances found a particularly juicy target in Captain Patrick Logan (1791-1830). Logan was a Scottish soldier, part of the 57th Regiment, who had seen service in the Peninsular Wars and the American War of 1812, initially leaving the service at the rank of Lieutenant in 1815, before re-joining the Regiment in 1819, when it was stationed in Ireland. He married an Irish woman, Letitia O’Beirne, and travelled with the Regiment to Sydney in 1824.

Logan was selected to take command of the struggling Moreton Bay Penal Settlement – at that time, a few tents and temporary buildings on a bend of the Brisbane River. He was nothing if not capable – permanent buildings were erected (two of which have survived Brisbane’s passion for erasing its past), roads built, stock grazed, crops grown, farming outstations established and daring explorations undertaken of the region.

However, Patrick Logan’s enduring fame arose from his treatment of the convicts who laboured under him to create the settlement. Tales of brutal lashings ordered by Logan are part of the folklore of Queensland. His reputation exists in books – “The Fell Tyrant, or The Suffering Convict” (1836 – republished in 2003), the song “Moreton Bay” and in newspaper articles in the 189 years since his death. However, the only editor who wrote unfavourably of Logan during his lifetime was one Edward Smith Hall.

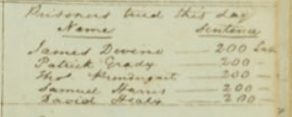

It is hard to assess just how harsh Logan was at a distance of two centuries. Corporal punishment is abhorrent to the 21st century conscience. Is he best compared with other Commandants of Moreton Bay? Surviving records are few – we have Spicer’s Diary from February 1828 to February 1829. This shows “Prisoners Tried This Day” from February 1828 to October 1828. The Trial Book of Moreton Bay survives from 1835 – 1842 and covers Clunie, Fyans and Gorman.

An unscientific search through Spicer’s Diary shows a steady increase in the punishments meted out – they increased from 25-50 lashes in the early pages to 100 – 200 in the later pages. Recording of punishments stops abruptly after what can only be imagined as a particularly gory day in October 1828 when five prisoners received 200 lashes each. The offences are not stated in the Diary, but certain names appear as having returned from absconding a few days prior to their trials. The absconders were given the most attention by the Commandant. David Bracewell, a famous runaway, was punished severely for two escapes in 1828.

Spicer’s Diary records one example of 300 lashes – dished out to an unfortunate Hugh Carberry for absconding, and a perusal of the trial book shows Clunie’s punishments for absconding to be generally in the hundreds of lashes, also for absconding. Fyans and Gorman as a rule preferred putting convicts in prison on bread and water. (Mr Carberry must have been particularly incorrigible, or an outright fool, having managed to get himself transported to Moreton Bay twice during Logan’s command. He survived.)

On 24 March 1830, The Monitor reported that Captain Logan was about to be relieved of his command after four years and queried the length of his tenure at the settlement. The 57th were getting ready to depart for India, and the 17th Regiment (“The Tigers”) would be stationed in Australia from 1830-1836. Captain James Oliphant Clunie would succeed Logan in October 1830.

The Libel Case

Three days later, Hall unleashed on Logan and Moreton Bay, using a letter of Thomas Matthews, written just prior to his execution for murdering another convict. Hall refrained from naming the Captain, and only once mentioned Moreton Bay as the settlement, but it depicts the Captain as a wantonly cruel man, who “in one of his mad fits and sent for all the cripples out of the hospital and flogged them every one.” After quoting part of the letter that described another flogging that turned fatal, Hall added, with no small satisfaction, “This is Matthews’ account of a penal settlement under General Darling’s administration.”

Newspapers reached the settlement by sea and it was nearly two months later that Logan wrote to the Colonial Secretary about Hall’s article, and a letter from Hall to a former Moreton Bay prisoner in which Logan was accused of murdering a prisoner named Swan. Logan requested that Hall be prosecuted for libel. By July, the lawyers were at ten paces, and a civil action was decided upon.

The closer Logan came to finishing his term at Moreton Bay, the bolder Hall became. Despite the lawsuit or perhaps because of it, Hall was relentless. On 14 August, another “letter” was published, and it was indisputably about Logan. The article described Logan’s “field days” of unmitigated violence and punishment on his “convincing ground”, his starved and heavily chained convicts, and his terrorising of Reverend Vincent. (Vincent did leave Moreton Bay after a very short time in 1828, citing difficulties with the military establishment there.)

Hall, now a free man thanks to the very Governor Darling he so loathed, resumed his campaign in The Monitor of 13 November 1830, unaware that his enemy was dead. A new proclamation had been released by Governor Darling, permitting Commandants of settlements full power to punish convicts under their charge for anything that did not attract a death sentence. Imprisonment, flogging and the use of the treadmill was at their discretion, and no doubt Captain Logan would take full advantage of that. Hope was not lost, according to Hall, because the British press had started to take notice of Governor Darling, and his conduct in the matter of Sudds and Thompson.

The following Wednesday, Hall buried the news of the death of Logan in a column between court cases and Police news, stating the bare facts of the death. Four days later, he reported the arrival of Logan’s remains in the shipping news. Shortly after, he queried the spectacle to be made of the Commandant’s funeral, and its impact on the public purse. But, Hall added piously, he would not recount the horrors of Logan’s behaviour while poor widowed Mrs Logan was still in the Colony.

Despite the Commandant’s death, Hall was not finished by a long shot. The stories continued in full force throughout 1831, and sporadically all the way up to 1838. In April 1831, he published an open letter to Lord Goderich, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Colonies, informing him that “Your Lordship is already aware, or you ought now to be made aware, that I am prepared to prove all the statements contained in those two, Journals, if you will call upon to do so. Captain Logan was at length ordered up to Sydney, and I was fully prepared on his arrival to cause three charges of murder to be laid against him. But Capt. L was murdered ere he left Moreton Bay, either by the convicts or the natives.”

By way of the final word, Hall published an interview with “Paddy Flynn”, who was actually John Flynn, a Tipperary chap who had spent 3 years at Moreton Bay for “repeatedly running away and an incorrigible character”. The interview reads like pure blarney, mixed with a deep sense of satisfaction.

THE LATE CAPTAIN LOGAN. We are happy to state, that according to the report of Paddy Flynn (whose hard case we reported lately), the late Captain Logan became a new man previously to his death. The following conversation took place between this man and ourselves:

EDITOR-Did the Blacks or Whites kill Captain Logan?

FLYNN-The Blacks. The Whites were very sorry for him.

EDITOR–How is that-I always understood he was a dreadful flogger?

FLYNN-So he was Sir until six months before he was murdered, but he took a change, and compared with what he was before, he was like an angel.

EDITOR- To what do you attribute the change?

FLYNN-God knows Sir! Some say he was converted by his wife.

EDITOR-I’ll tell you my friend. It was I who converted him.

FLYNN-God bless your Honour-but how came that about?

EDITOR-I published an account of his atrocities, accused him of flogging several men to death whom I mentioned by name, with all the circumstances. I also told him in the same paper, that all his public works, to erect which he was murdering the poor fellows employed thereon, were not worth six pence to the Nation, and that while nobody would thank him while he lived for his public zeal, the curses of hundreds would make his death miserable. What kind of a man is Captain Clunie, putting aside his flogging you, but for which he said he was sorry’?

FLYNN-Why Sir, Captain Clunie is a very good man. He is severe, but he hears all we have to say when we go to his Court, just the same as a trial in the Supreme Court; but if we are guilty, we are sure to catch it.

EDITOR-How are you fed now?

FLYNN-The provisions are greatly improved to what they used to be in Logan’s time; we have plenty, but we get no wheat meal, only maize meal.

EDITOR-Have you sufficient of that?

FLYNN–O yes Sir!

EDITOR-Then you ought to be satisfied. Maize meal, if sound and sweet; is as good as oatmeal, which the honest men of Scotland chiefly live upon, and you know Flynn, you do not take an excursion to Moreton Bay for pleasure, or to live like Aldermen.

FLYNN-Certainly not your Honour.

How very smug Hall must have felt. Some months later, Hall had occasion to feel smug again, as Governor Darling was relieved of his command. Darling blamed Hall. Hall was more than happy to wear the honours.

Edward Smith Hall closed The Monitor in 1838, and he helmed The Australian for a further ten years. Late in life, he took up a government appointment in, of all things, the Colonial Secretary’s Office. He died in 1860.

Governor Darling survived an English parliamentary enquiry into his conduct in relation to Sudds and Thompson. Thompson had even been located in Ireland and was preparing to testify when the committee decided it was best to wrap things up, and exonerated Darling in not very ringing terms. Darling died in 1858, no doubt to Edward Smith Hall’s immense satisfaction.

Sources:

Louis R. Cranfield, ‘Logan, Patrick (1791–1830)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967

- J. B. Kenny, ‘Hall, Edward Smith (1786–1860)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, (MUP), 1966

‘Darling, Sir Ralph (1772–1858)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, (MUP), 1966

Queensland State Archives Agency ID2753, Commandant’s Office, Moreton Bay

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5653, Chronological Register of Convicts at Moreton Bay

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5645, Book of Public Labour Performed by Crown Prisoners

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5646, Book of Trials

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 11 November 1826, page 3

Monitor (Sydney, NSW : 1826 – 1828), Friday 24 November 1826, page 4

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 25 November 1826, page 1

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 25 November 1826, page 2

Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 29 November 1826, page 1

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Wednesday 29 November 1826, page 3

Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 29 November 1826, page 2

Monitor (Sydney, NSW : 1826 – 1828), Friday 1 December 1826, page 5

Monitor (Sydney, NSW : 1826 – 1828), Friday 1 December 1826, page 1

Monitor (Sydney, NSW : 1826 – 1828), Friday 1 December 1826, page 4

Monitor (Sydney, NSW : 1826 – 1828), Friday 1 December 1826, page 3

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 2 December 1826, page 3

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 2 December 1826, page 2

Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Saturday 2 December 1826, page 2

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 2 December 1826, page 4

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 2 December 1826, page 3

Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 6 December 1826, page 2

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Wednesday 6 December 1826, page 2

Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 6 December 1826, page 2

Monitor (Sydney, NSW: 1826 – 1828), Friday 8 December 1826, page 3

Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 20 December 1826, page 2

Australian (Sydney, NSW: 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 3 January 1827, page 2

Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828 – 1838), Saturday 29 November 1828, page 8

Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828 – 1838), Saturday 3 October 1829, page 2

Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828 – 1838), Saturday 3 November 1832, page 2

Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828 – 1838), Saturday 3 October 1829, page 2

Sydney Monitor (NSW : 1828 – 1838), Saturday 11 July 1829, page 3

Monitor (Sydney, NSW: 1826 – 1828), Friday 8 December 1826, page 3

1 Comment