1824-1842 Moreton Bay Convict Settlement

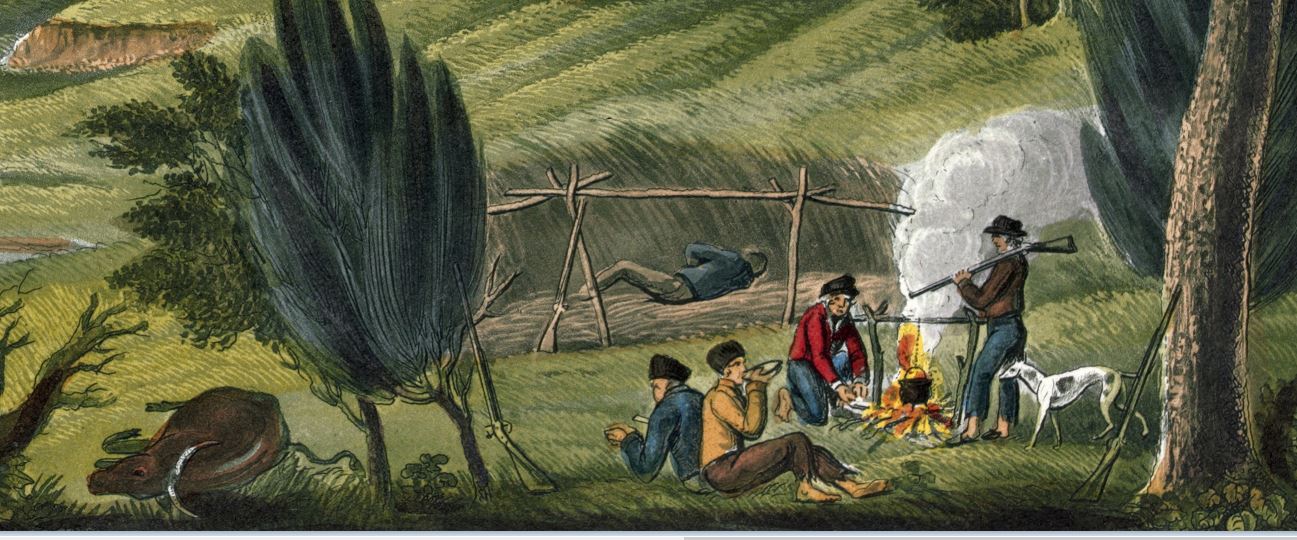

“Bushranging” was a term invented around 1805 to describe the actions of escaped convicts who took to the bush, often leading violent outlaw lives to secure food and avoid capture. Absconding became an attractive option in the penal settlements of Sydney (est. 1788) and Van Diemen’s Land (est. 1803). Food was scarce, rations were strict and punishments harsh. In the first few years, absconders took to living with the indigenous people; later, as free settlers began to form townships, a bushranger and his confederates could raid nearby farming hamlets for provisions.

The Moreton Bay penal colony was different. It was established in 1824, first at Redcliffe, then Brisbane, and it was designed to be isolated. No free settlement meant that there were no townships or farms to raid for food. If a man wanted to survive in the bush, he needed help. That help, at first, could only be provided by the indigenous people.

The first prisoner to abscond from Moreton Bay was Edward Mullens, who took to the bush on 16 June 1825. He was retaken and put right back on the barque “Lucy Ann” for Moreton Bay in April 1828. The second escapee, Henry Drummond, a 17 year old from England, absconded on 13 November 1825, never to be heard from again. It’s doubtful that the young man got very far. The third was John Sterry Baker, who ran on 08 January 1826, and handed himself in to a suitably astonished Commandant Gorman on 04 August 1840. Baker had been living with the indigenous people of the region, and had been accepted as Boraltchou, the return of a much-beloved deceased tribesman. James Davis or Duramboi was another convict runaway fortunate to become a valued member of an indigenous group.

Convicts would take to bushranging in pairs – Newman and Pittman on 14 January 1826, Butler and Fagan on 04 October 1826 or in small groups, such as Longbottom, Welsh and Smith. Two or three men might be able to survive and gather food, whereas if a convict was out alone, his chances of survival diminished.

Convict absconding became a thorn in the side of various Commandants over the years. Solutions suggested included being returned to Moreton Bay with no hope of release, increased lashings and being sent to the penal colony of last resort – Norfolk Island. None of this seemed to work, and in 1830, two escapees suffered very harsh penalties for their crimes on the run.

There was a certain kind of bushranger who would disappear off for gradually increasing periods, honing his skills as a bushman, gaining the trust of the indigenous people before dropping off the radar for years at a time. One of this class was a clever young man with a fondness for larceny. Sheik Brown or Browne made his way – dishonestly – from India to London, and then to Botany Bay and Moreton Bay. He absconded within a week of arrival on 02 June 1826.

Browne would make an art of absconding – at one point convincing a Sydney newspaper via an in-depth interview – that he was an explorer named Jose Koondianas, who had conquered Australia overland. The military authorities were not so easily taken in, and Mr Browne was returned to Moreton Bay. Until he decided to leave again.

Sheik Browne spent a lot of his time on the run with the indigenous people, but as the years wore on, he became less welcome. By 1837, a deputation of Bribie Island leaders had become so frustrated with the presence of four Moreton Bay convicts in their midst that they informed on them to the authorities in Brisbane Town. Sheik Browne, George Brown, James Ando and William Saunders had been staying on the Island, and paying way too much attention to the young women and girls. Commandant Fyans sent Saunders to Norfolk Island, and the rest were returned to Moreton Bay. Sheik Browne eventually met his end after the convict era, working in the Pine Rivers area, killed by the indigenous people there, either for forbidden love (according to Constance Campbell Petrie), or as part of the frontier skirmishes (according to the Moreton Bay Courier).

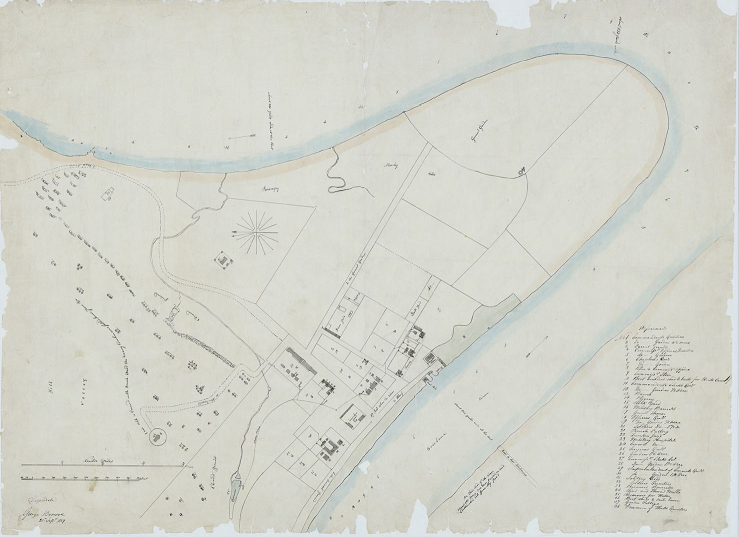

George Brown parleyed his ability to speak the local languages – gained whilst on the run – into a job as a constable. His knowledge of the local landscape led to a spot of cartography (see illustration), but the Commandant came to believe that he was leading the aborigines to rebellion, and George Brown’s briefly respectable career ended with a one-way trip to Sydney. Brown’s behaviour came the closest to the more traditional idea of the bushranger, and in later life, Brown became a real bushranger in New South Wales.

The Moreton Bay Convict settlement was broken up in 1839, and Brisbane Town was thrown open to free settlement in 1842, just in time for two convict absconders to be located and brought back with Andrew Petrie. Both men had lived as part of the indigenous groups of what is now the Fraser Coast, and had not been involved in skirmishes with the law. They were Davis (Duramboi) and David Bracewell (Wandi). Davis became a well-known merchant in Brisbane, and Bracewell went to work for the Commissioner of Crown Lands, where he died in a tree-felling mishap in 1844.

Settlers were gradually moving into the lands north of the Tweed River, but bushranging would not become widespread in Queensland for decades. A few skirmishes here and there, but the main focus for law enforcement for many years would be the brutal war of attrition between the indigenous people and white settlers.

Sources:

Queensland State Archives Agency ID2753, Commandant’s Office, Moreton Bay:

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5653, Chronological Register of Convicts at Moreton Bay

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5652, Book of Monthly Returns of Prisoners Maintained

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5645, Book of Public Labour Performed by Crown Prisoners (Spicer’s Diary)