Free Settlement to Separation to the Gold Rushes of the North.

Bushranging – once the term used to describe escaped convicts – gradually came to mean armed robbery and a life spent on the roads, dodging the law. In the 1820s and 1830s in New South Wales and Tasmania, men like Jack Donohue “The Wild Colonial Boy” of the song, and Martin Cash “Cash and Co” captured the public’s imagination. Unless, of course, you were a member of the public on the receiving end of their criminal intentions.

Moreton Bay and the regions beyond, thrown open to free settlement in 1842, experienced little of the bushrangers’ depredations. It was far too sparsely settled, and few had anything resembling wealth. Rural settlers spent their time and energy clearing land and dealing with the traditional owners of that land.

Gradually, townships began to form, and sheep and cattle stations (similar to American ranches) set up on vast rural runs. The mail started to travel throughout the Colony, and gradually, highway robbery travelled north of the Great Dividing Range.

The first known incursion of bushrangers into what is now Queensland occurred in 1849, when Mr William Richardson’s station “Glenelg” on McIntyre Brook – about half-way between Warwick and Cunnamulla – was robbed by two men, who stole two horses and an order book. One of the horses was Richardson’s prized “Goldfinder” and the order book was blank – as good as cash.

Conditions, warned the Moreton Bay Courier, were ideal for an outbreak of highway robbery.

“The whole of the great tracts of grazing country, within hundreds of miles of Moreton Bay, are entirely destitute of police. Two or three constables at Warwick, and an equally imposing force at Drayton, constitute the army of paladins that is to contest against the crimes of whites and blacks, in the districts of Moreton Bay, Darling Downs, Wide Bay, Burnett, and Maranoa!”

Sporadic crimes were committed over the next few years, but nothing on the almost industrial scale of the bushranging committed in the South. Citizens remained concerned and in Brisbane in 1853, being of somewhat shabby appearance could land a man in a spot of bother.

On Sunday last some of the residents in the Suburbs of South Brisbane were considerably alarmed by a man who was wandering about in the bush, and who entered some houses to seek food, which was given him. From his travel stained appearance and long beard he was suspected to be a bushranger, and the police having been put on the alert, Constable Booth succeeded in apprehending him, on Monday morning he was brought before the Bench next day, when it appeared that his name was Thomas Finan, and that he had been brought up as a vagrant, for living with the blacks, in February last. As the account he now gave of himself was not satisfactory to the Bench, he was sentenced, under the Vagrant Act, to seven days’ imprisonment in Brisbane gaol.

The same year, a trooper in the New England area wrote to the Moreton Bay Courier, giving a description of a man named Thomas alias John Heywood, who had been escaping from lock-ups and troubling locals, and who might come north to plunder afresh.

Heywood did indeed venture north – at least as far as McIntyre Brook, and tried to rob a public house of its cash box. Unfortunately for Mr Heywood, he was rash enough to talk about his plans, and as a consequence, they were foiled. He was shot and captured on the Clarence River, and sent to Sydney by the Iron Prince steamer, suitably, in irons.

In 1854, the assistant postman on the Callandoon run near Goondiwindi, made off with the mailbag and horse. He was supposed to have been a bushranger, which was a bit of a failure in employee screening on the part of Her Majesty’s Post.

Things were quiet on the armed outlaw front until after Separation in 1859. Queensland became a separate Colony, and gold was discovered in the north. All hell did not break out immediately, but the 1860s saw the arrival of some notorious characters from New South Wales, and the eventual development of local bushrangers.

To the south, the newly truncated Colony of New South Wales began to experience the most notorious era of bushranging, fuelled by the wealth of the goldfields, the wealth of the land, and a rural society marked by a huge gulf between the rich landowners and the struggling small farmers.

Bushrangers became more audacious, their raids more violent, and the press, aided by the electric telegraph, were able to report on their activities on a daily basis.

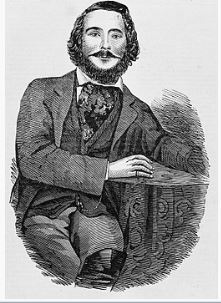

There was Frank Gardiner, a Scot who created a gang of bushrangers in New South Wales, famously robbed the Gold Escort at Eugowra in 1862, and then seemed to disappear into the ether in the following year. The gang was then led by Ben Hall, characterised in print as an honest man made dishonest by a corrupt police force.

Hall was joined by a Canadian immigrant, John Gilbert, and a young man named John Dunn. Dunn and Gilbert would kill police officers in later years.

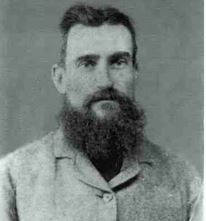

Harry Power escaped prison around this time, and resumed a life of bushranging before being caught, and the self-proclaimed Captain Thunderbolt, considered to be a “gentleman bushranger” took from the rich.

Another character, who rejoiced in the name of “Mad Dog” Morgan led a blood-thirsty life on the run, and no newspaper would characterise him as a victim or hero.

“Bushranging seems to have broken out in Northern Queensland.”

In the early 1860s, press and public attention was firmly on New South Wales, and its countryside apparently full of highwaymen. In Central Queensland, the new goldfields, and the riches they brought, began to attract some lawless characters.

‘Dear Sir,

I have to inform you that I have had the misfortune of being stuck up by two armed bushrangers, about fourteen days ago. They took from me one chestnut mare, branded JL on near shoulder, near eye blind from a spot on the sight, two saddles and bridles, and £35 in cash. One of them fired three shots at me; one ball went through my hat at the lower part of the ribbon and went out at the top, fortunately doing no harm as one would suppose by seeing the hat. The men were seen by the mailman two days after, on the road to Rockhampton, near Wilmott’s station on Funnell Creek. One was about 5 feet 8 inches in height, black bushy whiskers, and is known by the name of Jack Harty or Harvey, wore patent leather boots; one of the saddles had German-silver stirrup-irons. P.S. — I wish, to inform you that they have also passed and forged a number of cheques in this district. George Bolger, Sandy Creek, Fort Cooper, June 7th, 1863.’

This report led the Queensland Times to declare that bushranging had broken out in Northern Queensland.

Very little happened in the way of an outbreak, and little was heard on the subject of local bushranging until the Queensland Times asked in exasperation in January 1864:

“Who is the Queensland Correspondent of the Geelong Advertiser? He must entertain very extensive notions of the gullibility of the readers of that journal when he asks them to swallow the following story: -“Now, in connection with the escort, I shall make mention of a circumstance that has come to my knowledge, and that should be borne in mind by the policemen. Frank Gardiner, the celebrated New South Wales bushranger, has gone north, and doubtless he is on for a ‘little game’ after the free and easy fashion he adopted in the neighbouring colony.”

The Geelong Advertiser article went on to suggest that two notorious ladies, both with reputations blackened by the suspicious deaths of their husbands, consorted in Brisbane with the disguised bushranger. One was Madeline Smith of Glasgow, the other Mrs Winch of Rockhampton. Both suggestions were demonstrably untrue. The Glasgow Mrs Smith had not emigrated and was embarking on private life in Scotland after her scandals, and Mrs Winch was in durance vile. These idiotic claims meant that the whole of the article could be dismissed as fiction.

The trouble was, Frank Gardiner was in Queensland. Not with a murderess, but with his mistress Kate, the sister of Mrs Ben Hall. Gardiner was living near Rockhampton at Apis Creek as Mr Frank Christie, and running a small store with a business partner named Archibald D Craig, who was blissfully unaware of Mr Christie’s true identity. It was a shock when the plod came calling.

Gardiner had been very careful to set up his identity as Christie and intended to sever all ties with his life in New South Wales. Kate, however, rather rashly wrote a letter home, which was brought to the attention of the Police, who despatched Detectives McGlone and Pye to Queensland to recapture the scoundrel.

Posing as travellers to Peak Downs, the officers set up camp on 02 March. McGlone pretended to be sick, so that Pye and a trooper would purchase medicine for him at the store. They did not see Gardiner but were served by ‘Mrs Christie’. Later, McGlone went into the store and was served by ‘Mr Christie’ whom he recognised at once as Gardiner. The police retired to their camp, recruiting the assistance of a local landowner. The next morning as ‘Mr Christie’ left his shack to go to work, he was overpowered by Pye and McGlone. As the charge of robbing the Eugowra Gold Escort was read to Gardiner, he professed to be puzzled as to his activities in June 1862. He and a shocked Craig were taken into Rockhampton, and ‘Mrs Christie’ went along with them of her own will.

The extradition hearing at Rockhampton was accompanied by a trial of Craig and Kate for harbouring a bushranger. ‘Mrs Christie’ proved to be an unwavering witness, refusing to give any evidence that would incriminate herself, Christie or Craig. She even petitioned – successfully – to have her personal property returned to her. Craig and Kate were cleared of the charges against them and allowed to go.

Frank Gardiner was extradited to New South Wales, where, after endless delays and remands, he was sentenced to 32 years’ hard labour. In 1874, he appealed for a reduction in sentence, and was granted release by the wonderfully named Governor of New South Wales, Sir Hercules Robinson. Release conditional on leaving the Colony, never to return. Gardiner obliged, and took a boat to Hong Kong. He ended up in San Francisco, running a saloon. Records in San Francisco were damaged in the 1906 earthquake, and it is therefore hard to confirm whether Gardiner died a pauper in 1882 as reported in one Australian newspaper. It is also reported that he may have died in 1903 in Colorado, but this story cannot be confirmed.

Once the shock of having an actual New South Wales bushranger in their midst had subsided, Queenslanders could have been forgiven for thinking that perhaps bushranging was a foreign activity after all.

The next 40 years would prove them wrong.

Images: Wikipedia

Sources:

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 21 April 1849, page 2

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 28 April 1849, page 2

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 23 April 1853, page 3

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 7 May 1853, page 3

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 1 October 1853, page 2

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 29 October 1853, page 2

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 19 November 1853, page 2

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 1 July 1854, page 2

- Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1861 – 1864), Saturday 3 August 1861, page 3

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld.: 1860 – 1947), Thursday 2 July 1863, page 1

- Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Tuesday 7 July 1863, page 3

- Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1861 – 1864), Friday 24 July 1863, page 3

- Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Saturday 30 January 1864, page 3

- Rockhampton Bulletin and Central Queensland Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1871), Thursday 10 March 1864, page 2

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld.: 1860 – 1947), Thursday 10 March 1864, page 1

- Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1861 – 1864), Thursday 24 March 1864, page 2

- Edgar F. Penzig, ‘Gardiner, Francis (Frank) (1830–1903)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, (MUP), 1972