1865 – The year that everything changed.

We cannot omit to notice a very happy result of the advantages likely to accrue from telegraphic communication, adverted to by a gentleman who charged himself with what may be deemed the representation of the moral and religious aspect of the question. This gentleman stated that he foresaw in the Electric Telegraph an agent for the extinction of much of the crime with which the colonies were peculiarly disfigured – alluding, we presume, to the bushranging, so speedily put down in Queensland, but so rampant in New South Wales. But it is unnecessary and would prove tedious to enumerate the aid Telegraphic communication confers on every class of the community, save those at war with law and morality.

Ah, yes. Once that Gardiner fellow was off over the border, Queensland could enjoy the flowering of its separation undisturbed by those marauders. As 1865 began, Queensland was relatively untroubled by bushranging.

In New South Wales, the outlaw activity seemed to be reaching a peak with Ben Hall, Gilbert, Dun and Mad Dog Morgan more or less in charge of the back roads. In January alone Hall’s gang moved in on Goulburn, Dunn murdered a policeman and the even redoubtable Frank Gardiner tried to escape from gaol in Sydney. (Gardiner had lulled his captors into a false sense of security by impersonating a model prisoner. While they were very disappointed in him for fooling them, he didn’t manage to get very far.)

But north of the border, oh how we congratulated ourselves! On 11 February 1865, “Queenslander” wrote to the Brisbane Courier, berating the Colony of New South Wales:

“Again, why should such a magnificent colony as our own be dependent for its steam trade on a neighbour—and such a neighbour, bordering on a state of bankruptcy, and whose rulers are such imbeciles that they cannot even protect their unfortunate colonists from the depredations of a parcel of bushrangers; I say the sooner we drop all connection with such a neighbour the better.”

Hmph. So there.

After all, Constable Hart had disarmed and captured a bushranger outside of Gayndah, single-handed! Well, admittedly, the fellow was new to the outlaw profession and was obliviously leading his horse to a waterhole when Hart presented his firearm, and the obvious alternative. We were so pleased with ourselves that editorials started to proclaim our bushranger-repelling qualities:

It redounds to the credit of Queensland that our police have been instrumental in checking the career of a large number of the ruffians who have long assisted in protracting the reign of terror in New South Wales. We have been in imminent danger from the fancy which the bushranging community of the neighbouring colony had taken to flee “over the border ” to seek here immunity from the consequences of their crimes, or some respite from their arduous labours of sticking-up her Majesty’s mails and raiding her peaceful subjects; but so many have found this place “too hot to hold them,” that we now have some confidence that those who are still on the road, or who have taken to the bush, will not readily direct their steps northward.

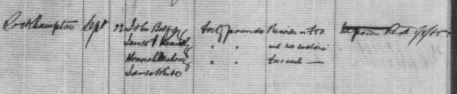

By the end of February, “the Queensland bushranger” MacPherson was in custody in New South Wales. A bushranger named George Gipson (alias Thom), and another man who looked suspicious were unsensationally arrested in Brisbane in March. Gipson was sent to New South Wales before he could range any bush in Queensland, and the suspect-looking chap got a free trip to Melbourne to be identified.

In the South, Morgan committed another murder, and extraordinarily detailed accounts of Hall, Gilbert and Dunn escaping an ambush filled the dailies. They seemed invincible. Then, in April 1865, everything changed.

First, “Mad Dog” Morgan was killed when trying to rob the Peechelba Station in Victoria on April 8, 1865. Then Ben Hall’s luck ran out, and he was ambushed and killed on 05 May 1865, near Forbes in New South Wales. When his body was brought back to the town, it was found to have 30 bullet wounds. Hall’s deputies, John Gilbert and John Dunn – both killers – were pursued to Binalong, New South Wales on 13 May 1865. Gilbert was killed, but Dunn managed to escape with the Police in hot pursuit.

And in Queensland, the Colony that had so glibly boasted of doing away with bushranging, it began in earnest. MacPherson’s charge in New South Wales was dropped, and he celebrated by escaping from custody and heading home.

As the bushrangers fell in the South, two men robbed travellers on the road from Chinchilla to Taroom, and the victims gave excellent descriptions of the bushrangers:

One a tall man, who was recognised by one of the bullock drivers as having been at work at Rosenthal about eighteen months ago, about six feet in height, with slight stoop, about twenty eight years of age, fair complexion, light sandy beard and whiskers; wore light tweed trousers, with black piping, blue coat much faded, red sash, and large neckerchief; had a large good looking brown horse, and blanket in valise on saddle; was armed with two revolvers. The second man was from 20 to 25 years of age, about 5 feet 5 inches in height, dark hair and eyes; wore a Scotch twill shirt, moleskin trousers, and wide-awake hat; had an excellent bay horse, with swag, and was armed with revolver and horse pistol.

The report of the incident ended with a note of foreboding: It is fully expected that the Condamine mail will be attacked. It left yesterday morning, and returns on Tuesday, when there will probably be more particulars.

While the Condamine mail was not robbed right away, someone forgot to tell the Warwick Argus that John Gilbert was dead.

Some excitement was occasioned in town on Thursday last by a rumour that the bushrangers Gilbert and Dunn had passed through the town on the previous Tuesday. The two men (one of whom bore some resemblance to Dunn’s description), were in possession of two good spring carts, which they offered for sale to various parties in town. Mr. Sub-Inspector Morris, accompanied by Constable Stretton, started at half-past five on Thursday evening in pursuit of the men, and came upon them the same evening encamped near Mr. Wienholt’s station. The police quickly presented their revolvers at the men, and challenged them to surrender, which they did at once, being under the impression that the disguised police were bushrangers and put their hands in their pockets to give over the money. The police having allayed their fears, threw handcuffs to them, which they at once placed on their wrists, the one assisting the other. A search was then made by the police, who discovered that the men were hawkers, and they were at once released, much to their gratification.

Oops.

In June, the two Condamine mail robbers were caught in the town of Jandowae, near Dalby. They turned out to be a couple of locals. Harry Quirk was described as a tall, wiry man with dark hair, a bullet head and a very bad countenance. He had been recently discharged from a stock-keeping job. The other chap was a bullock driver named Paddy, who was also newly unemployed, and he was tracked to an inn at Jandowae.

The capture involved an awful lot of police officers and indigenous trackers, after which the authorities were gifted with jaw-droppingly conclusive evidence. What Harry Quirk lacked in matinee idol looks, he made up for with a profound attention to detail and record-keeping. Possibly not the best idea to diarise the whole robbery, though:

The evidence is most conclusive; even the pieces of blanket with holes for their eyes, which they kept over their faces whilst robbing the mail, exactly fit Paddy’s blanket, which was found on him when he was taken at Jandowae. Harry Quirk kept a diary of the whole transaction, which the police took from his person. There is a full list of the stolen, cheques and orders in Quirk’s hand writing in his pocket-book, and the same cheques and orders have been found on their persons.

The threat of bushranging began to loom over small towns and remote stations. In the wake of the Frank Gardiner’s surprise capture in the very midst of innocent Queenslanders, people were seeing potential bushrangers everywhere. By now, everyone knew that Morgan, Hall and Gilbert had been killed, but Dunn and the dramatically named Captain Thunderbolt were still at large. They could lurk behind the scarves of any armed horseman, anywhere.

On 05 July 1865, two men stuck up a publican at the Coach and Horses Public House on the Rockhampton Road at Capella Creek. The reports in the Northern Argus provide the reader with an introduction to bushranger patois, and also an idea of the celebrity of Dunn and Thunderbolt.

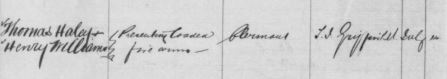

Thomas Haley and his young friend Henry Williams stayed at James Kennelly’s establishment at Capella Creek. While Williams propped up the bar, pretending to be rather drunker than he actually was, Haley decided to remove two guns from his belt and say to Kennelly, “I am the bloody man as can bail you coves up.” Kennelly took Haley outside to talk, or more precisely, to negotiate for his life. Haley said, “Old man, I wouldn’t shoot you for a trifle – you’re made of too bloody good stuff – I’d like to have another such as you,” and asked Kennelly if he could get hold of a couple of good “prads” in return for a share of gold from the next Escort. Kennelly asked what “prads” were, and Haley said, “Gammon you don’t know.”

(“Prad” was an informal term used in Australia and New Zealand in the 19th century, taken from the Dutch “paard” or horse. The use of “Gammon” is a little more complicated. It means different things in different parts of Australia. The Macquarie dictionary gives a number of meanings for the term – the best match for the conversation Haley had is “interjection – an exclamation of disbelief, equivalent to ‘as if’.”) KB

Before returning to the bar where Williams was waiting and making threats to anyone who would listen, Haley asked if Kennelly would take him for Dunn, the bushranger. Kennelly replied carefully that no, as far as he was aware, Dunn was a youth of nineteen. Haley proclaimed himself Dunn’s master, indeed “master of all of them, and could stick the whole lot up.” Sensing an ego in dire need of stroking, and aware of the presence of two pistols on Haley’s belt, Kennelly ventured, “I don’t know who you can be unless you are Captain Thunderbolt.” Haley relaxed and said, “You’re right.”

Inside, Williams, nursing a cordial and sherry warned Haley not to drink too much, “We must keep right,” but Haley was well on his way and eventually passed out at the bar. The dangerous outlaw had to be put to bed.

Kennelly had both men in custody by daylight – Haley was out cold. The vigilant Williams proved harder to subdue, struggling and objecting fiercely to being tied up by the Aboriginal man Kennelly brought to help in the capture.

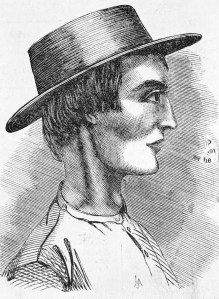

When the matter came up for committal hearing later that month, Williams – observed to be a tall, clean-shaven young man who resembled an engraving of Dunn brought from a Melbourne periodical – conducted a vigorous cross-examination of Kennelly.

Haley was “well known in this district … remembered as an excellent jockey, and as addicted to violent language when drunk, for which, however, he invariably apologised when sober.” Haley admitted that he had been very drunk and didn’t remember anything of the night.

Clearly the Rockhampton lock-up was not playing host to Thunderbolt and Dunn, and once the matter was called on for trial in September, the two men pled guilty to assaulting Kennelly. They each got three months’ imprisonment with hard labour in Rockhampton Gaol.

On 04 August, between the arrest and sentencing of Haley and Williams, a horse thief and bushranger named Edward Cain (also Kain) who went by the nickname “the snob” was caught on Gordon Downs Station at Capella. A Mr Allan Hughan, late of Victoria, and his men were camped on Belcombe Creek, and gave a marvellously florid Victorian account of the derring-do involved.

Consulting with two of my friends and my men, I arranged to seize him. Walking up to the camp, and sitting down beside him, I entered into conversation with those around, and himself, respecting the road, water, etc., for I had observed, as I thought, a knife in his hand, which I knew would be far more dangerous in a close struggle than a pistol. For fear of exciting his suspicions, I could not make a close examination, but sat still, hoping to see him put it down or to be off his guard. At a sign, my friend Mr. Donald Laird, made a dash on his side; I on mine; Mr. North threw himself upon him, and Mr. Richard Jones held his feet, he struggled to reach his revolver, which, loaded and capped, was in his belt, with much desperation ; but he had no chance, poor fellow, and in a few minutes I had him securely bound.

As Cain struggled, one of Hughan’s men assured him, “Oh, it’s no use, my fine fellow, you are in the hands of Victorians now!”

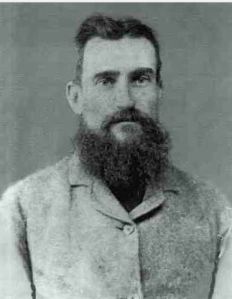

State Archives

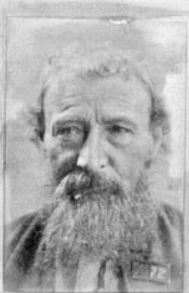

Something about the nickname “the snob” seemed familiar. And here he is – going under his various aliases- Cahill, Harry Parker, Edward Hartigan, Cain, Cliff, and of course, “the snob.” The first photograph was taken in 1875, when “the snob” was returned to custody amid a huge public fuss about lenient sentencing and recidivism . (Sounds familiar.)

The second photograph shows “the snob” 20 years and several prison terms later. Judging by the criminal history attached to the second mug shot, the indefatigable villain was separating people from their hard-earned coin as late as 1905. As far as one can tell from the thicket of aliases, “the snob” was an Irishman, born in the mid-1830s, who felt that there were more interesting ways of earning a livelihood than his stated occupation of boot-maker.

With Haley, Williams and “the snob” in custody for the rest of the year, James Alpin MacPherson, the Wild Scotchman, decided the time was ripe to recommence his criminal career in his adopted Colony. He robbed the Condamine and Taroom Mail in October, the Roma Mail in November, and the Gayndah and Maryborough Mail in December. Each time, he left a witness with a captivating story to tell and the post much lighter for those in the outback. His spectacular career will be reviewed in detail in Part 4.

As if outlaws weren’t hard enough to catch in Western Queensland, certain Police weren’t a huge help. In early November, “Flash” Harry Parker and Tom “The Doctor” Garner were in the custody of four constables. They were brought for an overnight stop at a station called Bingi, and treated to a good feed by the cook, and even permitted to play cards. When Tom the Doctor dealt a hand, he slipped his handcuffs off, and then politely put them back on afterwards.

The night passed without incident and in the morning, the group was preparing to leave. The Constables saddled up their own horses, but felt it was rather beneath their dignity as officers of the Crown to saddle up a prisoner’s horse. Flash Harry obliged, and saddled up his own steed. Within seconds, Flash Harry was off in the direction of the bush, getting away so quickly that the gunshots fired by the Constables couldn’t reach him.

The journalist who recounted this sorry, but slightly hilarious tale, bemoaned the posting of soft, citified officers to remote townships. Even more disturbing was the quality or decided lack thereof, of their mounts. It was a shame for the model police of a model Colony to be outshone in the saddle by a few ruffians.

No doubt James MacPherson was resting under a shady tree, with some purloined journals and books, laughing himself silly.

And so ended the year when bushranging came to Queensland in no uncertain terms.

In the next instalment, the Wild Scotchman will finish his career on the roads, and a Wild Frenchman will fill the void. Then, an apparently respectable public servant will commit a shocking crime of murder and bushranging. And three bushrangers found lasting infamy and the drop by murdering a local business identity.

SOURCES

Rockhampton Bulletin and Central Queensland Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1871), Tuesday 10 January 1865, page 2.

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser Wed 15 Feb 1865.

Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 22 February 1865, page 2

Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 28 February 1865, page 3

Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 22 February 1865, page 2

Brisbane Courier (Qld : 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 12 April 1865, page 3

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947), Saturday 24 June 1865, page 4

Rockhampton Bulletin and Central Queensland Advertiser (Qld. : 1861 – 1871), Saturday 12 August 1865, page 2

Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Monday 30 October 1865, page 3

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld. : 1861 – 1908), Thursday 30 November 1865, page 4

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld. : 1861 – 1908), Tuesday 12 December 1865, page 4