The ability to control one’s child, especially one’s male child, was a mark of successful parenting in the 19th century. For families of the middle class and respectable working class, children were expected to make themselves generally useful and be subject to parental control before they began to work to help support the family (generally in their very early teens).

making themselves generally useful.

The misery that occurred when a father died and left his wife and children unprovided for, in the language of the time, was seen in the cases of Charles Dennison and Francis Dunlop. The family turmoil experienced when a mother died – or more sensationally – left the family, helped keep the Proserpine in business.

Single Fathers

In January 1873, two young Toowoomba lads, William Pooler (10) and John Pooler (12), did something very naughty. They stole a small jewellery box from the wonderfully named Isabella Smoother. It contained a pair of earrings valued at 20 shillings. They then went to another wonderfully named person, Gaw Chong, who gave them 1 shilling and some stamps for the earrings. However larcenous these boys were, they were not good at business.

Detective Kilfedder reunited Isabella Smoother and her earrings and arrested the two boys for larceny. At the first mention of the case, the boy’s father, John Pooler, told a sad but all too familiar story. His wife had died, and he had a large family. His youngest children were being looked after by an elder daughter while he worked as a smithy at the Government workshop to pay for it all. The two boys had become uncontrollable, and he could not keep them at home. If the Bench was willing to consider a reformatory, he would gladly contribute a sum to their upkeep.

After an adjournment to consider the hulk-related sentencing options, the Bench ordered William to the hulk Proserpine for five years, and the older brother John for three. Mr Pooler was ordered to contribute 8 s. per week to their support.

John Pooler arrived at the Proserpine standing 4 feet ½ inches, with a fair complexion, light brown eyes and fair hair, described as a farm worker. He was released two years into his five-year sentence, at the same time as little brother William (4 feet 1, also a farm worker, with grey eyes and light auburn hair).

At the end of the same year, little Samuel Robson – not quite eight years old – had taken to running away. A constable found him at a beach near Pialba on his third excursion in the bush. The first time, local indigenous people brought him back to his father, the second he stayed away one night and returned of his own accord.

Samuel’s exasperated father fronted the bench at Maryborough on December 9, 1873 and told a familiar tale. His wife had left a year ago, he did not know where she was or if she would return. The boy was uncontrollable, and he feared for his safety if he kept running away.

George Robson practically begged the Magistrate to put young Samuel into the Reformatory, offering to pay “a modest sum” towards his support. The Bench remanded the boy for a couple of days, suggesting that his father supply the lad with some clothes at the watch-house, before releasing the little tyke back home for one more chance.

In February 1874, Samuel ran away again. This time he was found after a week, sheltering under a banana tree, by the wonderfully named Prince Coleman who worked at Mr Cleary’s farm. Prince Coleman took the boy to the Cleary house, where he was bathed and fed, before being forwarded to the Police again.

Thomas Hawkins, George Robson’s employer, gave evidence that the father had spent three days searching for his son in the bush, and that the boy was impossible to keep at home.

George Robson gave evidence that his son was 8 ½ years old and this was his fifth time away from home. Once again, he offered to pay towards his son’s upkeep (a moderate amount please) if the boy could be taken somewhere to be cared for. The bench relented, and little Samuel was sent to the Proserpine for four years.

Thus the Proserpine received the 3 feet 11 ½ inch child, noted as having blue eyes and dark hair. Samuel was released two years early in 1876 at the ripe old age of ten.

The Families with a Delinquent Lad

Sometimes a family was intact, respectable even, but could not keep their youngsters under control.

William Gilbert was the son of a well-known Brisbane butcher, and apparently had a respectable, stable home. His journey to the Proserpine is quite beautifully described by the Brisbane Courier of 17 August 1871:

A precocious youth of ten summers, named William John Gilbert, whose parents -hard-working, honest people – live in Edward street, Spring Hill, was brought up for petty larceny, the specific charge being that he had stolen a toy ship from a boy named Joseph Green, one of his neighbours. He was arrested on the 15th instant by Detective Kilfedder.

Though young in years he seems to have acquired a good deal of very questionable experience, having been on numerous occasions in the hands of the police authorities on a variety of charges, but his tender years had hitherto screened him from punishment. Incredible, too, as it may seem, he had not, as a rule, slept at home since he was six years of age, preferring the shelter to be found about the wharves, and such like places. He was a terror to the boys of the neighbourhood, as he delighted in many pastimes not generally appreciated. On the application of the father, who agreed to pay 5s. weekly towards his maintenance, the little fire eater was sent for three years to the Reformatory School on board the Proserpine, in the Bay.

Young Gilbert served the whole of his three-year sentence and returned to society’s good graces aged fourteen.

Henry Glynn’s family was also intact, but they were running out of patience with him. He was thirteen, and although very young-looking and small for his age, and he could not be kept at home.

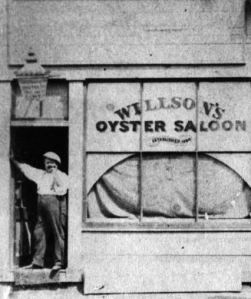

His father Michael Glynn worked as a cook in an Oyster saloon, earning 25 s. a week, and had his wife and three other children to support. (Looking at the other parents’ evidence, Mr Glynn was decidedly less well-off than Mr Pooler and Mr Gilbert.)

Henry had started to stay away from home for longer periods, spending only one or two nights a week at home. His truancy at the Normal School, and then a Catholic school in the Valley ended any hope of an academic career, and he could not be trusted to work for his living. Mr Glynn suspected his son associated with a bad class of companions and added piously that he did not want to be disgraced by Henry’s conduct.

On June 3 1871, Henry was brought before the Bench as a neglected child, and the Magistrate, on hearing Michael Glynn’s evidence, sent the boy to the Proserpine for five years. He served three years, being released on February 6 1874.

Let’s hope he didn’t bring any further disgrace to the Oyster Saloon’s cook.

None of these boys embarked on adult crime sprees, meaning that they were amenable to the reform offered by the Proserpine. I suspect it had more to do with the child’s receptiveness, rather than the measures taken by the custodians on the hulk.

Sources

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 3 June 1873, page 3

Toowoomba Chronicle and Queensland Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1875), Saturday 1 February 1873, page 3

Toowoomba Chronicle and Queensland Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1875), Saturday 8 February 1873, page 3

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Thursday 17 August 1871, page 2

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld.: 1860 – 1947), Thursday 11 December 1873, page 2

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld.: 1860 – 1947), Saturday 14 February 1874, page 2