Few institutions have undergone an ordeal the like of the troubles of the Brisbane Hospital in the 1880s. Accused of medical, financial and managerial incompetence, the hospital battled its way through catastrophic outbreaks of typhoid and emerged at the end of the decade being lavishly praised by the same press that had vilified it earlier.

The decade began quietly. The annual report of the hospital for 1880 noted with evident relief that the hospital had been spared the devastating fever outbreaks that had marked the latter part of the 1870s. Perhaps, the committee felt, this marked a turning point in the hospital’s fortunes. Sadly, this would not be the case.

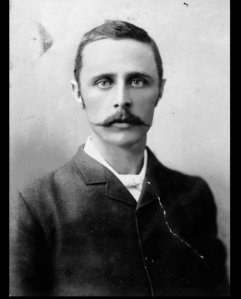

THE NEW RESIDENT-SURGEON

In early 1882, Dr Thomson, resident-surgeon, felt it was time to step down from the full-time role. The hospital committee, chaired by the redoubtable John Petrie, thanked him for his dedicated service, and called for applicants for the role. The recruitment process was conducted by post, and on Tuesday 9 May 1882, the committee decided on 31-year-old Dr Leighton Kesteven, at that time working in Gympie. The Secretary was instructed to write to Dr Kesteven at once, confirming his appointment, and urging his prompt attendance. The role of Assistant-Surgeon was established and conferred on an eager, very young medico by the name of Dr Ernest Sandford Jackson. So far, so good.

By August 1882, it had become evident that Dr Kesteven possessed a remarkable talent for upsetting the local worthies. Rev. Mr J Stewart wrote to the committee to complain of being excluded from the fever ward by the resident surgeon, who responded that it was better to limit visitors to patients who were delirious. Mr Forsyth was scandalised by the Doctor’s use of hospital linens in his residence, but his censure was overruled by Chairman Petrie, who recalled allowing Kesteven to have a few items on loan, you know, until the Doctor’s wife arrived to take charge of his household.

Mr Forsyth was not satisfied, and drew the committee’s attention to the refusal of a delivery of fish, allegedly at the surgeon’s abrupt direction, the ruffled feelings of the Captain of the Norseman, who supplied the refused fish, not to mention the continued unhappiness of Rev Stewart. The resident surgeon wearily undertook to investigate the missed fish dinners, but it was all too much for Mr Forsyth who called Dr Kesteven “cowardly, ungentlemanly and unmanly,” and conducted a mini-audit of all things resident-surgeon-related, with the eager assistance of the Hospital secretary Mr Bourne. It did not expose any impropriety on Kesteven’s part, but showed that coherent record-keeping wasn’t one of the committee’s virtues, and the matter was quietly dropped.

A number of skirmishes broke out in the letters pages in the following weeks, but Dr Kesteven had the support of the Chairman and the qualified support of most of the committee until October 28, when a patient named Robert Kingston died, and Dr Kesteven’s career with the Brisbane Hospital was doomed.

THE DEATH OF ROBERT KINGSTON

Immigrant ships bearing infected patients to the Colony remained a concern three decades after Doctor Ballow went to assist a stricken colleague attending the ship Emigrant, and lost his life in the process. Robert Kingston Jr, travelling with his extended family on the Chyebassa, complained to the ship’s doctor of ill health.

Dr Kesteven, together with a Dr Henry Symons, examined Kingston on Sunday evening and found no indicia of disease, but admitted him to the fever ward, presumably as a precaution. The next day, Hospital staff told the resident-surgeon that Kingston had passed a bad night, and showed symptoms of typhoid. By that evening, Mr Kingston had died. Visiting surgeon Dr Canaan, together with Kesteven, conducted the post-mortem, which showed that the young man had been suffering acute intestinal ulceration and blood poisoning prior to the typhoid, which took his life.

Besides being an unbearable loss for his family, none of this would have been particularly sensational, had Mr Kingston Senior not claimed that Dr Kesteven told his son he was ‘shamming’ his illness at the time of the initial consultation.

On 02 November 1882, a member of the Hospital Committee, Mr Guthrie, hastened to present a letter damning Dr Kesteven to the committee, stating that:

“his conduct to the relatives of the unfortunate lad, which I cannot characterise as anything but brutal, and such as to show me that, from this and other cases that have come before me during the past week, he is totally unfit for the position he holds. I may simply mention that if you refuse to suspend him and have an independent inquiry, I shall avail myself of Rule 13 and call a meeting of subscribers.”

A magisterial inquiry (Coroner’s Inquest) was held into Kingston’s death, at which the ‘shamming’ comment was raised, but denied by the medical men concerned.

On 09 November, Dr Kesteven had the Courier-Mail publish a letter of approbation signed by every patient in the Hospital. He also issued a writ for damages of £2000 against Guthrie for charging him publicly with gross neglect.

On 16 November, following the evidence taken at the inquest, Guthrie apologised in writing. Kesteven withdrew his writ the following day, but the damage was done. Editorials questioned the fitness of everyone concerned to hold office at the Hospital, and although both Guthrie and Forsyth resigned, peace did not reign.

“A poor surgeon, a fraud and a qualified quack.”

Visiting Doctors (the equivalent of consultant specialists today) complained to the committee of being invited to witness or assist at important surgeries, only to find Dr Kesteven absent without explanation at the time and place appointed. Those Doctors happened to be three of the most eminent medical practitioners in the Colony – Dr Kevin Izod O’Doherty, Dr Joseph Bancroft and Kesteven’s own predecessor, Dr Thomson.

It was one thing to lack bedside manner and lose a patient, it seemed, but quite another to mess about with surgical schedules.

DISMISSAL AND A COURT CASE

Testy committee meetings ensued, and the resident surgeon was asked to tender his resignation. He refused to oblige for six weeks, leaving the committee ‘no choice’ but to dismiss him in February 1883. For the sake of continuity, Dr Jackson was appointed resident-surgeon, taking over the most responsible medical job in the Colony at the age of twenty-three.

Dr Kesteven announced his intention to take up private practice, and was also appointed surgeon of the Artillery, Number 3 Battery. He then commenced civil action against Mr Darvall, treasurer of the Brisbane Hospital, for unfair dismissal and damages consequent thereon.

The case was argued by distinguished and talented legal figures, and it was Dr Kesteven’s misfortune to find himself under cross-examination by Sir Samuel Griffith (future Chief Justice, Premier and High Court Justice), instructed by Virgil Power, another future Justice, and founder of an eponymous legal dynasty that endures to this day. Dr Kesteven’s testiness and lack of respect for his colleagues was laid bare in open Court.

He “did not know what Dr O’Doherty’s reputation was, did not know he was regarded as a distinguished and skilful surgeon, witness considered him a poor surgeon, did not know what his medical education was, had often wondered whether he had had any; was not aware that he was educated under some of the most distinguished medical men in France, was aware that many people thought Dr. Thomson a clever physician; witness thought he was a fraud; Dr. Bancroft had the reputation of being a very clever man amongst some people; witness thought he was a qualified quack; had held these opinions since he had an opportunity of seeing them practise, did not know Dr. Bancroft was a very distinguished scientific scholar; the shortest possible time in which a man could get a medical degree in England was four years, in Scotland one could get one in about three years and a half.”

A poor surgeon, a fraud and a qualified quack. Dr Kesteven, unsurprisingly, lost his action, having demonstrated why he lost the confidence of Hospital management . He remained in Queensland for another decade, establishing himself as a skilled doctor, who had perhaps learned the price of making enemies. His son, Hereward Leighton Kesteven, a babe in arms when his father railed against the medical establishment, went on to become one of Australia’s most beloved and distinguished medical gentlemen.

But the Brisbane Hospital would have endure much worse in the years to come.

Wow, thank you! A brilliant summary of the time of my great-grandfather Dr. Leighton Kesteven at Brisbane Hospital. I’m writing a biography of him, must go back and look at my long, detailed chapter, and rethink!

LikeLike

I think Dr Kesteven improved over time, like a good wine. His encounter with the doings at the RBH was early in his career, and he may have been a little incautious, particularly with his assessment of his peers in his evidence. He certainly went on to be held in great esteem. Congratulations on your biography, and thank you for your kind words.

LikeLike

It would be extremely interesting to read this biography! I am an evolutionary biologist and very much appreciate your great-great-grandfather’s work on vertebrate evolution. He was something of a scientific heretic, but his ideas may still be useful today.

LikeLike