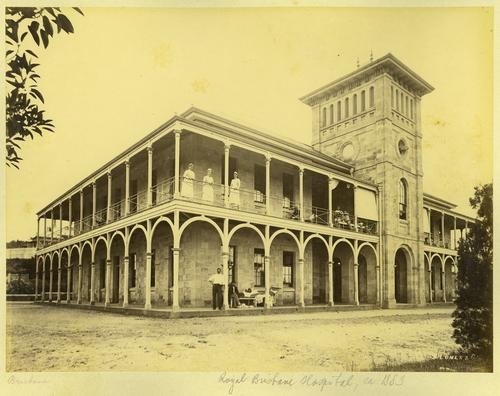

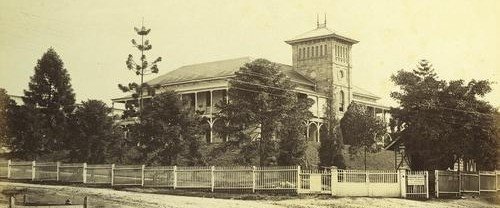

If the early 1880s had been trying for the Brisbane Hospital, 1885 was a nightmare. Staff went missing, patients went missing and money went missing. The Hospital was the subject of a daring undercover story in the Courier, and an unfavourable Auditor-General’s Department report – the first conducted, apparently, in eighteen years.

The year began innocently enough. At the committee meeting on 26 February 1885, the assembled worthies considered that the actions of the neighbouring Sick Children’s Hospital committee in inserting a gate in their mutual fence “a high-handed proceeding.” The secretary was instructed to write a letter.

Said secretary reported that a clerk and former wardsman named Thomas J Davis, had left work at 8 am the Thursday before and had not been seen or heard from since. Davis was described as a steady, quiet employee, about 38 years of age. This was entirely out of character, and the police had been informed. I imagine the secretary wrote a letter. It seems that Davis came to no harm on his sojourn, and returned to work as a wardsman later in the year.

The Hospital was beleaguered on several sides in 1885 – patient complaints, inquiries into deaths, financial mismanagement and upheaval.

PATIENT COMPLAINTS

The Hospital was beset with patient complaints all year, and its committee was its own worst enemy when it came to responding. Complaints were aired in the fortnightly committee meetings, which were open to the public and an increasingly cynical press. The committee was observed to dismiss any number of complaints, from the deadly serious to the comical, in the same high-handed manner. Little wonder that the Courier, hitherto an ally of the Hospital, decided to do a little undercover reporting.

Waiting for the Doctor

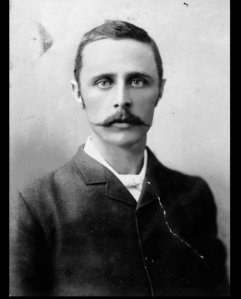

At a meeting in April, committee member Moses Ward brought up the concerns of a patient who had been in the hospital for two weeks without seeing a doctor. The response was brusque.

“Dr Jackson said that the man’s statement was wrong. He must have been seen by the surgeon, who had been around several times. He (Dr Jackson) with Dr Thomson had talked the man’s case over at his bedside; whether latter spoke to the man he knew not. Mr Ward thought that talking the case over could not be called a consultation.”

The Doctor made a couple of testy remarks about the case being not serious, and the matter was dropped.

Elderly woman turned away

The following month, Mr Sanderson from the Courier gave a ticket of admission to an elderly lady with a chest infection who was then turned away from the Hospital, and apparently told they “couldn’t be bothered” with her. He added that he would not subscribe to, or take subscriptions to the hospital under the present management.

Dr Jackson, whilst denying the language used, stated that the old woman was a candidate for the convalescent home at Dunwich, he hadn’t any spare beds and the healthy young person who accompanied her to the hospital could have looked after her. The Chairman remarked that there were people who thought that the hospital was but a lodging-house.

The Secretary was instructed to write to Mr Sanderson, informing him that the committee was satisfied with the Doctor’s response. I doubt that anyone else was.

Complaint against a Doctor

A Mrs Allard reported that she took her sick daughter to the City Dispensary (a sort of outpatient general practice in the centre of town, with Hospital Doctors rostered in attendance) on a Friday, waited for hours, but no doctor attended. The following Monday, they presented again at the dispensary, where she alleged that Doctor Edward O’Doherty had been rude, and his treatment perfunctory. The girl died that night.

Dr Jackson admitted that he had been going to take the Friday shift at the Dispensary in place of Dr O’Doherty, but had been busy at the Hospital and forgot.

Dr O’Doherty recalled meeting an agitated woman with a daughter suffering from pneumonia. He considered that the mother should have taken the child to get Hospital treatment when she found the dispensary unattended. Also, he knew that Allard was not her real name. The committee thus dismissed Mrs Allard and her dead child with no further investigation.

Complaint against a Nurse

In those days, convalescent patients were asked to perform light duties around the Hospital, if the doctor cleared them to, and if they were willing. This did not sit well with Mr John Grout. Mr Grout complained about this practice, and against Nurse Patterson, who, when not pestering and nagging him to do manual labour, was in the habit of singing before 8 pm. (Perhaps it was more acceptable to sing after 8 pm, but alas that question was not addressed.)

The committee heard from Dr Jackson, who said that Mr Grout was nearly well when the request to work was put to him. Nurse Patterson gave evidence that she could do nothing to please Mr Grout. She did not sing, but may have, in the course of her duties, hummed some airs.

“The committee decided that the charges were of too trivial a nature to be taken serious notice of, but the nurse was cautioned against doing anything to irritate patients.”

The Brisbane Courier

Possibly including a moratorium on the airs.

Complaint of Mr Duel

Mr George Duel’s wife died in the Hospital, and he didn’t know until he arrived to visit her the following day. He went to the offices of The Telegraph the next day to describe the treatment he received.

As it happened, the Hospital committee was in session the day Mr Duel visited.

The person whose duty it would be to give notice of a death said that he had forgotten to do so; and that, being new to his work he had not yet fully grasped the situation. This was taken to satisfy the committee, but it was poor solace to the husband. On remarking that if he had not happened to call, he supposed his wife would have been buried also without his knowledge, he was told that the authorities would have looked him up on account of the expense of the funeral.

The Telegraph

The Hospital, in its official meeting the following Tuesday, put the failure to contact Mr Duel down to his residence in an inconvenient suburb.

INQUIRIES AND INQUESTS

On several occasions, deaths occurred in the Hospital that required the scrutiny of the Coroner or a special inquiry, and could not be smoothed over by the committee as part of correspondence inward.

Mrs Laughlin

On October 21 1885, a fire broke out at the Tollerton Boarding House in Charlotte street. The landlady, Mrs Laughlin and her baby son, received critical burns. Archibald Kerr drove them to the Hospital in his cab, and rang the bell at the gate-house.

From that moment, the sequence of events is hard to determine, and varies according to the teller. Kerr stated that he immediately told the gatekeeper Abraham Price that he had an accident case. The gatekeeper stated that he heard only “I want to get in.” Price said that he needed to cover himself with a coat, and when dressed, saw the gate was open and the cab proceeding up to the Hospital. Kerr said that he had a verbal disagreement with Price about which alarm bell should be, or had been rung. At one point, a passenger in the cab got out and opened the gate to let the cab in.

Kerr then encountered the wonderfully-named Burns Hollingdrake, night watchman, who was either offhand and the slow to act (Kerr) or polite and prompt (Hollingdrake). The doctor was woken, but his dog got out and added to the commotion.

Mrs Laughlin and her son had been waiting in agony for 15-20 minutes from arriving at the gate, and being taken inside for treatment. Both were so badly burned that they passed away that day. The delays they encountered were such that the Hospital was forced to conduct a special inquiry, which concluded in December with its report.

Abraham Rice was found to have not used proper diligence in finding out the nature of the emergency, and should have rung the alarm bell, which led to confusion and delay. It appeared that he was quite deaf, which was not ideal in a gatekeeper at a Hospital. To put it mildly. He was given notice, but the committee felt badly at leaving such an old man unemployed, and resolved to keep him on as a carpenter. Care would have to be taken in selecting a new gatekeeper. Mr Wilson put it simply: “We want a man with some intelligence and tact.”

Margaret Carroll

Margaret Carroll was a mother of six young children, the youngest was six weeks old. She had symptoms of a chill, and then began talking to herself. The following day she was noisy and violent, so her husband went to Mr P7etrie to get a ticket of admission to the Hospital. She was in a weak condition on arrival, and was nearly turned away by Dr Hare, who felt that the Hospital was not the place for her.

Producing Mr Petrie’s ticket gained her a consultation with Dr Jackson and admission for a couple of days. Her husband was told that the Hospital was going to send Margaret to the Reception House – a place for people to be admitted for “lunacy.” They did, and she died there after 48 hours. Her husband felt that she should not have been moved there while still weak.

Edgar Driver

In August, a man named Edgar Driver escaped the Hospital, found his way home, and passed away. He had been suffering from erysipelas in his face, which is a chronic condition causing severe pain and best treated by antibiotics (which were over 50 years in the future).

Driver was attended by Dr Rendle at his home after his escape and before passing away. He told Rendle that he was neglected and mistreated at the Hospital and had escaped. The journey from the Hospital to Driver’s home in South Brisbane would have required a cab and ferry, but the exposure he suffered through being out at night when quite ill hastened his death.

Burns Hollingdrake, Charles Locke (warders), Dr Jackson and Mary Clarke (night nurse) all gave evidence, but Hospital management, although given an opportunity to appear, chose not to.

It seemed that Mr Driver had been seen by Dr Jackson on the day of his admission, treatment was ordered and given, but Mr Driver could not bear the face masks prescribed. Distressed and probably delirious, Driver had run away.

“Driver during the night had expressed a desire to leave hospital, and that he was persuaded to remain until morning. Subsequently during the temporary absence of the watch-man about daybreak Driver put his clothes on and was going away when he was met by the watchman, who endeavoured to prevent him leaving. Driver, however, climbed the fence, and remained on the other side some little time talking. The watchman represented to him that at this time Driver appeared to be sensible.”

Evidence of Charles Locke

IN THE BRISBANE HOSPITAL – article and fallout

A journalist from the Brisbane Courier gave an account of his undercover trip to the Brisbane Hospital in that paper on Saturday 29 August 1885. The writer was “made up” as a station hand to disguise his identity. I will include the committee article in full as a separate post, but here is a synopsis.

‘Ferguson’ was made to wait in the hot sun, prior to being examined by Dr Jackson, who thrust a rubber tube down his throat, and recommended admission. Dr Miller took his history, which seemed to focus mainly on his antecedents.

Once in his ward, he was ordered to undress and get into bed, a process that took two paragraphs. He noted the decor and fit-out, and was peeved at the unsanctioned wearing of hats indoors. He fell asleep and missed his dinner of sago and milk.

One of the nurses did not pay him attention, but sang a lot. There was nothing interesting to read. His tea was three slices of rough bread, with fatty butter and undrinkable tea. He had difficulty sleeping that night, was given medicine, and Dr Jackson made brief rounds at 11pm.

The next morning, he missed his wash, was served sago made with water rather than milk, and was thus able to swallow with difficulty when Dr Jackson asked him for a demonstration. The dinner he was given included some oily beef tea, and sago, which he could not bring himself to eat. After being given a dose of medicine, he checked himself out a day earlier than intended, and went home to a bath, clean clothes and dinner. That’s it.

Much of the sensation the article caused was due to rumours he repeated about the screening-off of patients who were about the speed with which the mortuary basket came to remove any dead patients. As if it would be healthy to leave the dead lingering about.

The rest of the shock was reserved for young, chatty nurses and the state of the meals. It seems mild stuff compared to the 1884 Figaro article, “The Horror of the Brisbane Hospital,” but was enough to set the letter pages alight for weeks, and caused a report to be prepared for the Colonial Secretary.

One wag suggested deploying the Courier’s intrepid reporter to infiltrate the larrikin gangs who were “yelling and roaring like fiends” along Queen Street late at night. Alas, the invitation of “A Sufferer” was not taken up. The mean streets would have to remain mean for the time being.

Of the more serious correspondents who signed himself “Secretary,” and who had, in a previous life, been secretary to a hospital, had some reasonable points to raise about diet, ward types and specialists’ visits. But most of his censure was directed to “idle, gossiping nurses.” There was, he felt “a want of order.”

Another writer, who could have chosen a more euphonious pseudonym than “Eczema,” remarked that the writer accused the nurses chiefly of “the atrocious crime of youth.”

One nurse was so upset by the whole business that she resigned.

MATTERS ARISING: Hospital management

There was a clumsily handled dispute with Mr Costin (a well-respected local businessman) over billing for medicines and equipment to the Hospital. The mutual unhappiness continued for months, with Mr Costin eventually ‘crashing’ a committee meeting to have his pleas heard.

The Secretary

The Hospital Secretary, Mr James Leete Bourne, had negotiated a payment in exchange for the extra duties he had been performing by arriving at the Hospital at 7 am to receive supplies. He felt that he was a much-burdened man, particularly when the Matron became ill and it was proposed to extend his duties still further. Matters reached a crisis in September.

Mr Bourne really had to protest. He was expected to conduct stocktakes on top of everything else. The report of that Committee meeting showed that a rift had developed in the committee in all things Mr Bourne-related. Dr Jackson in particular had little patience for the Secretary’s harrumphing.

Mr. BOURNE said he had done it and had put up with a good deal more than he ought to have done while doing it. If he were to continue it, however, he would have to come over to the hospital at 6 o’clock in the morning. He would have to receive these goods and keep the store book. During the last nine or ten weeks, while the matron was ill, he had done so; but he objected to being sneered at and interfered with by the nurses or anybody else.

The CHAIRMAN remarked that if anyone had interfered with or sneered at him he ought to have reported the matter to the committee.

DR. JACKSON thought it was decided that the secretary should do this work.

Mr. BOURNE (producing the store-book): It has never been settled.

Mr Bourne stated his intention to do the work, under protest, and hand in his resignation. No-one seemed to be anxious to try and dissuade him, so he made good his threat to resign, and set about finding himself a more congenial occupation for a man of his talents. It was a regrettable end to a 17-year association with the Hospital.

Incidentally, at the same meeting, our old friend Rev Stewart succeeded in having his visitation rights restored.

Hospital Accounts

The Courier reported parliamentary estimates for the preceding financial year, and noticed a discrepancy of over 1000 pounds between what Sir Samuel Griffiths reported to the house and the Hospital’s own reports. Whilst a correspondent did ease matters somewhat by pointing out how the discrepancies could be interpreted, the office of the Colonial Secretary was concerned enough to order a full inspection by the Auditor-general’s department.

The Auditor-General’s report was unflattering to Hospital management, the Hospital regular private auditor but mostly to the departed Secretary, Mr Bourne.

The basis of my examination of the receipts was from the collector’s butts and the secretary’s cash and bank deposit book. I found that the dates of receipts did not correspond with the cash-book entries. The banking was most irregular, amounts having been on hand for one, two, and three months. This branch of Mr. Bourne’s work shows gross carelessness. The examination of his collections, which were received and paid over by the committee’s collector, discloses that he (Mr. Bourne) has not accounted for several items, amounting to £23 2s. 6d., as shown on statement attached hereto. Two further sums which were received, but could not be traced by me, require explanation.

Report of the Auditor General

The new Secretary, Mr Payne, was instructed to write to Mr Bourne.

Mr Bourne’s response

Mr Bourne gave his input in no uncertain terms. First to the Committee by letter and then to the press. Part of his defence sounds doubtful – a diabolically cunning office boy – but beyond that, he was probably just a careless man who felt overwhelmed by his duties. He was certainly distressed by the imputation of dishonesty, and left the Colony, auctioning his des res and all of his goods and chattels.

“I take exception to the charge of carelessness preferred against me in the said report, either as to the manner of keeping the accounts, which is the same that has been in vogue throughout my term of office, or in the matter of the deficiency of the money, the boy’s method being so subtle, that without previous knowledge of his failing, detection by me was almost impossible. It was his duty to read out the subscribers’ names and amounts from the ticket-book, while I entered them in the cash book. In doing so he would pass over the amount he intended to appropriate, and in my temporary absence from the office take the keys from my pocket and abstract the money from the safe.”

The treasurer resigns

The audit ended another committee member’s association with the Hospital- Mr Webster resigned as Treasurer, admitting that the new post-audit requirements were beyond him.

The hellish year actually served to make the Hospital a better institution. Being forced to examine its practices from admission to audit, and severing ties with certain staff who could no longer manage their duties meant a better-run institution. Dr Jackson won praise for creating and managing a nurse training program that improved patient care and no doubt discouraged any friskiness or tendency to burst into song.

The typhoid outbreaks would continue in the years to come, but the Hospital, in association a concerted public works program, was able to manage them.