Thomas Ellison Brown was better off when people left him alone. The trouble was, they wouldn’t. People hounded him all his life, and it always went badly when they did.

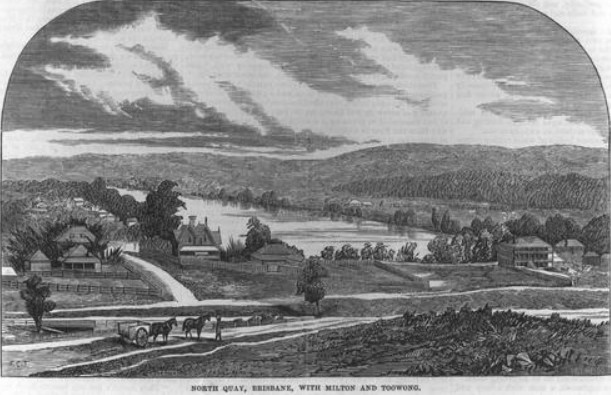

Born in Hull, Yorkshire in 1845 to Samuel and Hannah Brown, Thomas emigrated to Australia in 1862. He wanted to make his way in the new world, but failure dogged him at every step. He settled in Wharf Street in Brisbane town as a gardener, only to find himself insolvent in 1876.

Later on, Brown would have cause to shake his head at the idea of high and mighty Miskin, of all people, taking over his money. Mr Miskin, the prominent solicitor, the Mayor of Toowong, the great entomologist. The man who ran away with his bloody governess!

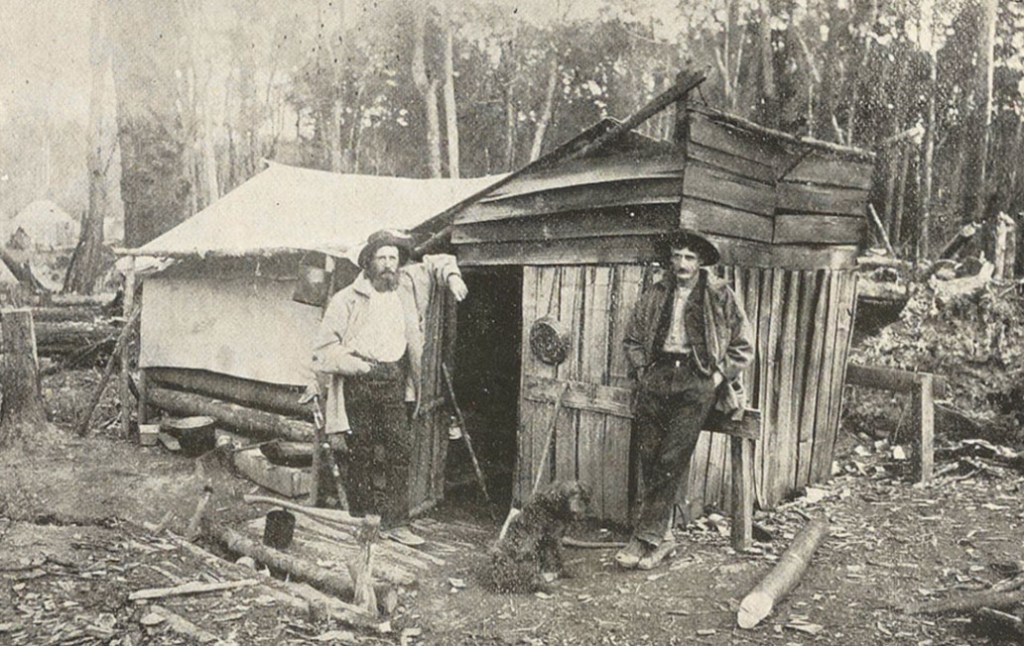

But Miskin’s fall from grace would be a long way in the future. Thomas Ellison Brown took himself out of town, and continued working as a gardener, whilst living in a hut in Herbert’s paddock, Milton. His neighbours generally kept their distance, regarding Brown as a sort of half-witted hermit, but the local lads teased and tormented him, throwing stones at his humpy and calling him “Jack the Sponger.” They wouldn’t leave him alone.

On Sunday 25 March 1883, matters came to a head. A group of locals in their early 20s – John Murphy, his brother Patrick, Joseph Bryant, Arthur Ebenston, Arthur Bound and Thomas Connelly -were larking around Herbert’s Paddock and throwing stones at Brown’s humpy. A Cingalese man was bathing in a waterhole in the paddock and might have drawn their attention more had Thomas Brown not tired of their racket and stone-throwing and decided to do something about it.

Brown emerged from his humpy with a revolver, ran towards them, and fired in the direction of Patrick Murphy, shouting “I saw you throw a stone. Get out of the paddock.” “What will I get out of the paddock for?” drawled Murphy. “I will shoot you,” replied Brown. “You need not frighten me with that,” said Murphy, indicating the revolver.

Thomas Brown lunged at Murphy and the pair exchanged blows. In the struggle, Patrick Murphy tried to take the gun from Brown, who dodged him and fired. “Has he shot you?” asked John Murphy, and his brother replied, “Yes, I did not think the man would do it.”

Patrick Murphy did not seem badly injured, and walked home, assisted by Arthur Ebenston. On the way, Murphy clutched at his side and came up with a small bullet, which he handed to Ebenston.

At dinner with his family later that day, Murphy dismissed the injury, telling his mother he would get over it. He was more seriously wounded than he realized, the bullet had pierced his bowel, and he died in agony within 24 hours of the shooting.

Thomas Ellison Brown was charged with Patrick Murphy’s murder.

On Brown’s first appearance in Court, the evidence was read over, and witnesses were called. Brown gave spectators the impression of a well-educated and thoughtful man, if a little odd. He was remanded in custody for his trial in the Supreme Court later that year.

The matter came before the Supreme Court in May. In the two months since the shooting, Thomas Ellison Brown had been bothered by strangers again. The solicitor and counsel he had been provided with were strangers to him. They thought he should plead insanity, which irritated him no end. Doctors were brought to the goal to examine him. Such a parade of doctors. Eight or nine of them, all trying to prove him insane. Pestering him.

After reviewing all the evidence, the jury found Brown guilty of manslaughter rather than murder, and the learned judge called upon the defendant to make any statements he wished prior to sentencing.

Thomas Ellison Brown, allowed to speak for himself at last, rose to the occasion. He was not insane he averred, and he thanked the jury for determining that he was capable of understanding the charges and the proceedings. He felt that this alone was enough to counter all of those doctors. Insanity, said Brown, was struggling with a man with a loaded gun. He had been under constant attack from those youths – days of it – and the tragic events of that Sunday was the culmination of the terror. The provocation had been great.

The Judge sentenced Thomas Ellison Brown to imprisonment for life, noting the duty of the law to discourage “un-English” crimes involving firearms and knives. (What an English crime was His Honour didn’t specify.)

The Queensland Times opined that Brown would spend his life sentence in Woogaroo Asylum because “The doctors say that he is decidedly crazy.”

Brown did not spend his sentence at Woogaroo, because the Figaro found him at St Helena the following year. The paper had commissioned a series of investigative articles on the Island prison, using released informants and case studies to draw attention to conditions at the prison, and also the vast disparity in sentencing that led men there. After comparing the sentences handed out to a poor cattle thief (three years), a wealthy squatter cattle thief (a fine), and a patricide (four years), he turned to Brown.

“Thomas E. Brown, convicted on the 28th May, 1883, of manslaughter, and on whom a life sentence was inflicted, is a victim of the Milton larrikins, who irritated him until he sent one of their number to his death, and himself into perpetual imprisonment. He works in the tailor’s shop refusing to accept the usual indulgence granted to working prisoners, as he thinks that by so doing he would be acquiescing in his sentence. His particular hallucination is that if he were allowed to communicate with Mr. Gladstone, or the Queen, he would be at once liberated, and he has petitioned the Government to allow him to do so. His last petition was returned endorsed by the Under-Colonial Secretary as follows: —‘This man must not be allowed to petition or address the office in any way.—(Signed) Gray.’”

Brown did a decent stretch of time, presumably still under the impression that freedom was just a well-directed petition away, and settled in Zillmere, in a place picturesquely named Zillman’s Waterholes. He was getting on in years, and still preferred his own company in rustic surrounds. In fact, his dwelling was so rustic, it didn’t have running water, meaning that Brown had to bathe in one of Zillman’s waterholes. Isolation didn’t mean that people weren’t bothering him. His lifestyle was not deemed picturesque by the decent folk of Zillmere. They wanted him, his hut and his outdoor bathroom gone.

On the morning of Sunday February 2, 1902, a 15-year-old girl named Elizabeth Prichard was walking home from Sunday School with her sisters at Zillmere. As they passed a scrubby area, a naked man with a bag (or something similar) on his head, ran out of the bush and grabbed Elizabeth. An attempted indecent assault ensued, interrupted mercifully by two passing men, who chased the man away.

The Police were called and directed to Brown by a number of locals. Brown was agitated when questioned, and claimed to have been bathing recently, which was why he was half-dressed. The Police seemed satisfied at first with Brown’s explanation but were pressed by locals to make an arrest.

While something terrible happened to young Elizabeth and her companions, it was very difficult to prove that Brown was responsible for it. He faced two trials, both of which resulted in deadlocked juries. On both occasions, the inclination of the majority of jurors was to acquit. Brown’s defense case included evidence of a physical infirmity that would make chasing a young girl impossible, and markings on his body due to a chronic skin condition that would be easily noticed by anyone (the girls and the pursuers) if they saw him naked. Brown was, the judge observed in summing up, a person that the victim’s father and other Crown witnesses, wanted to leave the district.

In the end, the Crown offered a nolle prosequi in lieu of a third trial, and Thomas Ellison Brown was left alone again to bathe al fresco and avoid human contact as much as possible.

In February 1905, 69-year-old Thomas Ellison Brown passed away in the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum (a palliative care facility for the poor and aged). He was not the kind of man who would seek out assistance, even in infirmity, but at least he found a place to die with proper beds and shelter. I hope that people didn’t bother him.

SOURCES:

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Thursday 29 March 1883– Page 2

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Friday 30 March 1883– Page 3

Article– The Week (Brisbane, Qld. : 1876 – 1934): Saturday 31 March 1883– Page 15

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Thursday 31 May 1883– Page 2

Article– Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld. : 1861 – 1908): Thursday 31 May 1883– Page 2

Article– Queensland Figaro (Brisbane, Qld. : 1883 – 1885): Saturday 2 August 1884– Page 23

Article– Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1878 – 1954): Friday 7 February 1902– Page 5

Article– The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, Qld. : 1874 – 1954): Friday 7 February 1902– Page 5

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Friday 7 February 1902– Page 2

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Thursday 13 February 1902– Page 2

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Friday 14 February 1902– Page 2

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Thursday 20 February 1902– Page 5

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Monday 24 February 1902– Page 2

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Thursday 20 March 1902– Page 2

Article– The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933): Saturday 22 March 1902– Page 11

Article– The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933): Wednesday 26 March 1902– Page 11

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Friday 28 March 1902– Page 3

Article– The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933): Friday 28 March 1902– Page 2

Article– The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947): Tuesday 14 February 1905– Page 4