Thomas John Augustus Griffin was a worried man. His past was catching up with him, and he needed money – fast – so that he could satisfy his debts, get away and possibly fake his death. Again.

He could access some fast money, arrange an inside job, but it would be risky. He may have to kill to get the money.

Griffin was born in County Antrim, Ireland in 1832, and joined the Royal Constabulary before volunteering for service in the Crimean War. He was a successful soldier, decorated twice and commissioned in the Turkish contingent.

Quite the up and coming (but impecunious) chap, he turned his attentions to the Colonies and the fortune that would surely come to an ambitious man.

Fortune appeared in the shape of a widow, Mrs Harriet Klisser, a fellow-passenger on the ship from Europe to Melbourne. Mrs Klisser was in possession of a generous sum from her late husband, and Griffin decided that starting his new life with a spot of financial backing would be just the ticket. He wooed her ardently, and a marriage took place on arrival.

Thomas Griffin’s Irish charm wore off quite quickly as far as Harriet was concerned, and when they parted, she also parted with half of her fortune.

Thomas decided to head north to Sydney and arranged for news of his untimely passing to reach Harriet in Melbourne.

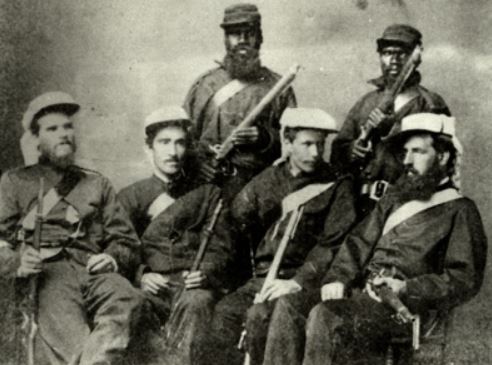

and sword. Of course. SLQ.

Venturing even further north, Thomas Griffin saw opportunity in the new Colony of Queensland. He joined the Police and rose through the ranks with breathtaking speed, going from humble plod to Clerk of Petty Sessions to Police Magistrate to Gold Commissioner in less than ten years.

Those witnessing his ascension noticed that he was romantically attached to a woman who was the sister of a prominent politician. Promoted far above his ability, he unwisely assumed an imperious air and quickly alienated those below him.

Meanwhile, the widow Griffin noticed an official announcement of the appointment of one Thomas John Augustus Griffin as a Police Magistrate in Queensland and smelled a rat. Enquiries through her solicitor, Mr Reed, reached Griffin, who made an unexpected visit to Melbourne. For his health. Fearful of discovery, Griffin agreed to pay his “widow” £25 per quarter for her silence.

The pressure of his financial obligations led him to gambling. The fear of exposure was overwhelming. But he didn’t change his arrogant behaviour – in fact, he became worse.

The Clermont Chief Magistrate, Oscar de Satgė, was made aware of an official complaint about Griffin that had not reached him. Griffin had stolen the letter before it could reach its intended audience. De Satgė was furious and demanded an inquiry into Griffin’s conduct.

Griffin cleverly avoided any official findings of guilt because the inquiry was held in Brisbane, hundreds of miles from any witnesses who could speak out about him. Sudden transfers to ever-higher positions ensured that Griffin kept one step ahead of his critics.

Griffin took to gambling with the Chinese at mining camps, losing heavily, and foolishly stopped paying his wife. Harriet was anxious that his payments resume immediately. That society engagement was in jeopardy, and Griffin needed cover his debts.

Necessity overtook good judgement, so in October 1868, Griffin conceived a plan to rob the Gold Escort, which was in his charge. Against procedure, he insisted on accompanying the troopers of the escort, having quickly paid off the Chinese with part of the money. He decided to stage a robbery of the rest of the money while the escort was encamped at the Mackenzie River.

The escort had noticed something “off” about their tea earlier in the journey, and Griffin may have tried to drug Constables Power and Cahill on the fateful night. Whether the troopers failed to fall asleep as planned, or fought back, is unknown. Griffin shot both men in the middle of the night and took the remaining cash.

Not guilty in this instance. (QSA)

After innocently enquiring (in front of witnesses) if anyone had seen the two troopers, Griffin went on his way the next day, giving those witnesses a story of having been lost in the bush during the night and hearing a gunshot. He had made a show of looking for Edward Hartigan (a bushranger nicknamed “the Snob”) before the killings in what he probably thought was a clever misdirection.

The bodies of Cahill and Power were found in the remains of the camp. Both men had been shot in the head. The evidence at the scene pointed to Griffin, and when located, he went quietly. He maintained a series of conflicting alibis, and an aggressively innocent demeanour.

But there was too much of the money from the robbery with him. His secrets were out or would be very soon. He was charged with two murders, tried in front of a fascinated public and finally executed at Rockhampton Gaol on 01 June, 1868. He was all of 36 years old.

In death, there was still scandal clinging to Thomas Griffin. His corpse was illegally dug up and the head removed. An inquiry was held but could find no culprit. The head, according to legend, reposed for many years in private hands.

Constables John Francis Power and Patrick William Cahill are considered to be the first two Police Officers to be murdered in Queensland. Two young Irishmen making their way in a new country who were heartlessly killed so that another Irishman could avoid a public disgrace.