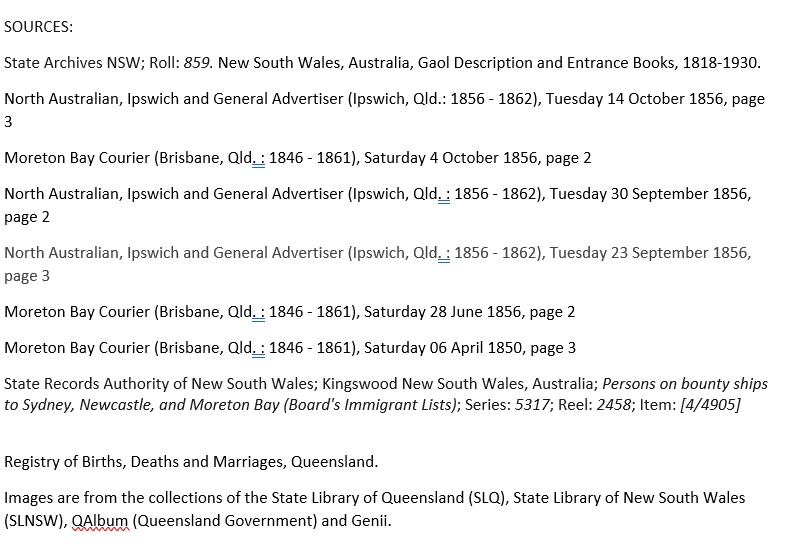

Murdered by her husband and blamed by society.

Around 10:30 on the night of 23 June 1856, residents of Brisbane Town heard screams from a cottage near George Street. It was a working-class neighbourhood, and raised voices were common, but this time it was the voice of a woman crying out “Murder!”

It turned out to be 26-year-old Annie “Nancy” McCoy, wife of a labouring man named Robert McCoy. She was begging him not to kill her.

Early life.

Nancy’s life had always been hard – she was born Anne McGee in Belfast about 1830, and was orphaned by the death of her parents, John and Jane McGee. At 18, she travelled to Australia on the Earl Grey in 1848, as part of the Assisted Immigration program. She was in good health, her usefulness was assessed as good, she had no relations in the Colony, was suited to work as a house servant, and assigned to Moreton Bay.

In September 1849, Nancy married Robert McCoy in Brisbane and they had their first child, George in January 1850 and Mary Jane in 1854.

Robert was a sawyer, quite tall for the time at 5 feet 10, and possessed of a temper. In 1850, he barely escaped conviction for what was literally a dog fight. McCoy had been walking is dog past a Mr Walker’s house, when Walker’s dogs barked and ran at McCoy’s dog. McCoy’s dog responded in kind, Walker intervened and the two men came to blows.

23 June 1856, 10:30 pm

After being beaten and kicked by her husband, a dying Nancy McCoy staggered to the home of Mr Orr, where her kindly neighbours tried to assist her, but she was beyond help.

The evidence given at the inquest was harrowing. It painted a picture of a woman who lived in fear of her drunken husband’s rages, the careless brutality of his treatment of her, and the final horror revealed by the post-mortem. There will be a lot of quotes in this post – the words of those involved telling a compelling story.

The Inquest, 24 June 1856.

The witnesses

“I have heard frequent quarrels between prisoner and his wife. I have also seen Mrs. McCoy on previous occasions leave the house and walk down by the fence as if waiting till he was quiet, or go to sleep, till she could go back with safety. When I got on my hat and went into the verandah again, the noise had ceased. May not have heard the commencement. I then returned to the house and in a few minutes, I went into the verandah again; I noticed a woman, whom I supposed to have been McCoy’s wife, standing against the post at the corner of the next allotment. I thought that the prisoner perhaps had come home with a glass, and as formerly, I thought that she was waiting till her husband would go to sleep I did not take any further notice, quarrels being frequent in that neighbourhood.” William Anthony Brown, of Mary Street, Brisbane.

“I was standing on the verandah, and I went into the yard at the back of the house and saw the deceased lying on the ground. She was crying murder! Her husband came and dragged her indoors. She told him she could walk; but he kept his hold and dragged her indoors. He set her on the steps in the house and she implored him to have mercy on her. She told him to think of her poor inside; but he struck her twice and knocked her down.” Charlotte Gower, of George Street, Brisbane.

“She asked him to have mercy on her, and he kept on ordering her to get out of the house. He kicked her while lying there – he kicked her twice. She was lying quiet, as if insensible. He ordered her to get out of the house, and she told him to have the feelings of a father and think about her poor inside. He said what h–l about her inside. She got up, fastened up her hair and sat up. He told her to go out; she asked him to be kind to the children, and he told her: never mind the children; and that if she didn’t get out by J—s he would make a corpse of her.” Jane Dunlop, of George Street, Brisbane.

On the verandah of Mr. Orr’s house, Nancy was tended to by Dr Cannan, the Orr family, Thomas Walley and William Brown. She asked for a glass of water, but was unable to drink it. Samuel Sneyd, the Chief Constable, came and oversaw Mrs McCoy’s removal to the hospital. She had blood over one side of her face from bleeding from the right ear and eye. No pulse had been detected for some time, and she was pronounced dead when she arrived at the hospital.

While Samuel Sneyd went to the McCoy house, arresting a very drunk and disbelieving Robert McCoy and ensuring a constable stayed with the children overnight, Dr Frederick Barton conducted a post-mortem on Nancy McCoy at the Brisbane Hospital.

He found that, as well as suffering a number of contusions to her head and torso, she had haemorrhaged from the uterus, and that she was six months pregnant. The baby died with her.

The Coroner -In the evidence it is stated that she was kicked and knocked down: I apprehend that the question of the juror is, as to whether, in your opinion, that would be likely to produce the hemorrhage? Dr. Barton :-I have no doubt that it would.

Inquest.

Sneyd examined the house and yard in the morning light, as the children were taken into the care of the hospital, now effectively orphans. There was blood in the house and yard, and a trail leading to the Orr’s house, where Nancy McCoy died. In the yard, he detected marks on the ground, as if someone had used their hands to struggle to get up.

“I have nothing to say; I have no recollection of what I done.”

Robert McCoy.

The Trial

The evidence led at the trial was the same as given at the inquest. Mr Milford appeared for Robert McCoy, who did not give or call evidence.

After cross-examining all of the Crown witnesses, largely with a view to depicting the victim as someone who drank too much, “Mr. Milford then addressed the jury on behalf of the prisoner, and laid great stress on the fact of the parties being addicted to intemperate habits, and suggested that a fall might have occasioned deceased’s death.”

This was all too much for the Crown Prosecutor, who had already summed up for the jury. He exercised his right to reply to the closing argument Mr Milford had just given.

This is the last time someone spoke up for Nancy McCoy:

“The Crown Prosecutor … commented severely on the conduct of the prisoner, which he characterised as that of a brute, and stated that he felt bound to remark that the doctrines broached in the speech of the prisoner’s counsel were calculated to do a great deal of harm, if allowed to go uncontroverted. He then gave a different version of the law as laid down by Mr. Milford, and contended that the case amounted to one of murder, as violent blows and kicks were proved to have been inflicted without any justifiable cause and while the deceased was in a state of pregnancy, which any man in his ordinary senses must have known would terminate fatally.”

The Judge stated, “However the Court might lean to the side of mercy, there was no evidence whatever to prove that there had been such provocation, and they (the jury) were bound to decide only according to the evidence that had been adduced before them.”

Robert McCoy was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death.

The Petition.

Before long, a petition was started in Brisbane, seeking clemency against the death sentence, which was quite reasonable. However, the petition, and the public debate around it, centred on the behaviour of the victim, rather than the idea of extending mercy to the murderer.

“We learn from that evidence he threatened, in case his wife did not immediately leave the house, that he would make her a corpse. These words certainly imply malice aforethought and a murderous intent, but how many persons are there under the influence of partial intoxication, who frequently use similar threats without the slightest intention of ever fulfilling them?”

Moreton Bay Courier

Indeed, how many people haven’t threatened their pregnant wife with imminent death after a couple of beverages?

“For every effect there is a cause, and doubtless there was a cause, a starting point from which arose McCoy’s fatal quarrel with his wife. But is it right to assume that all the wrong was committed by him? Shall we shut our eyes to the fact that the deceased was an habitual drunkard, daily and hourly giving her husband provocation, and that she was in a state of liquor the very afternoon preceding her death? Shall we make no allowance for the exasperation naturally felt by a man, who, tired and hungry after a hard day’s work, finds his wife on his return away from home and on enquiry discovers her at some public house, or worse still, in the lock-up? This is no fanciful picture of the imagination, but a stern and dismal reality in McCoy’s case, as could be proved if occasion required it. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your most obedient servant, ONE WHO SIGNED THE PETITION.”

The inquest and trial do not disclose that Nancy had a history of arrests for drunkenness. Her name does not appear in the list of “inebriates” or “worshippers of Bacchus” that the Moreton Bay Courier entertained its readers with. Chief Constable Sneyd did give evidence that he had seen her drunk before, but that she had called on him to assist with her husband’s violence more than once. None of the witnesses who attended her in her last moments believed that she had been drinking.

The Governor General has been pleased.

“REPRIEVE .–We understand that intelligence has arrived by the ‘Yarra Yarra’ to the effect that his Excellency the Governor-General has been pleased to exercise the prerogative of mercy in the case of the condemned criminal Robert McCoy, and has commuted the sentence of death passed against him, to transportation for fifteen years, with hard labour, the three first years in irons.”

This mercy was not extended to Chinese and indigenous people, who were often convicted of murder on much less evidence, and executed. It was right to reprieve the death sentence, but not to blame the pregnant young woman for her own death, and exercise mercy in the name of pestered husbands. Robert McCoy was sent to Sydney to serve his sentence.

I am still haunted by the image of a young woman, standing by her fence in the moonlight, waiting until it was safe to go home.