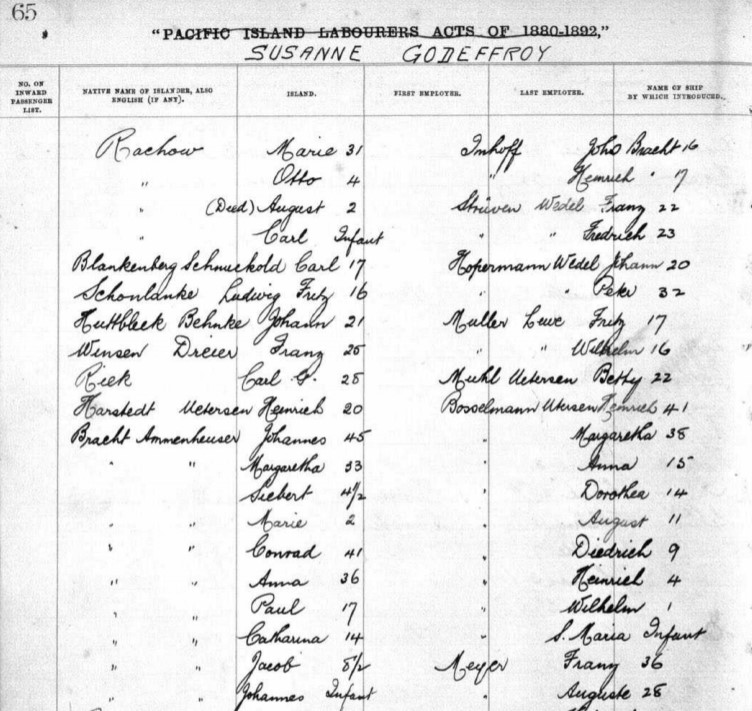

The immigrant ship the Susanne Godeffroy departed Hamburg on 06 May and arrived in Queensland on 06 September 1865, carrying a cargo of hard-working and hopeful immigrant German families ready to try their luck in the New World. Among them was the Ammenhauser family – brothers Johannes and Conrad and their respective wives and children.

Johannes and his wife Margretha settled in the Maryborough district and raised three little ones. Their son Seibert was the eldest child, and he was rather a naughty boy.

In 1872, when Seibert was 11 years old, Johannes felt he had lost control of his son. The boy did not want to go to school, and Johannes’ tactic of paying him a shilling a week to attend failed. Seibert happily took the money but did not darken the door of any classroom. The boy told fibs – Johannes remarked that “if he says ten words, I would not believe one.” Lately, the lad had been borrowing money from their neighbours, claiming the money was for his parents.

In July that year, Seibert’s luck, and Johannes’ patience, ran out. Neighbour Thomas Edwards had £12 stolen from him, and Patrick Kelly lost £5. Both men had used the hitherto infallible method of hiding cash under the mattress.

Patrick Kelly suspected young Seibert, who had been hanging around his property. Seibert, who might have been a prolific liar, was not a very good liar. He told Kelly that he had planted the money in the scrub. Kelly accompanied the scamp to the area in question, but the money could not be found.

Kelly then took Siebert home to Margretha and announced to her that he was arresting her son for larceny. Margretha was sure her son wouldn’t do that. Kelly stood firm and Constable Malachi Cahill was put on the case.

Cahill set out to investigate Patrick Kelly’s lost £5 and took the lad and Kelly back to the scrub to see if the money was where Seibert said it was. Thomas Edwards was passing by and noticed the boy with the constable looking about. Edwards recalled the lost £12 from under his mattress, but had not said anything about it yet. He availed himself of this opportunity.

Constable Cahill took Seibert back to the Ammenhauser’s home, and the story the boy told got stranger. Again, the lad claimed to have planted the money in the scrub, and again it was not found. On approaching the house, Seibert said that he had given the money to his mother, and that she would have put it in the safe with the eggbox or planted it under a shingle.

Margretha Ammenhauser, nursing a new baby, denied any knowledge of the stolen money. As far as she knew, the family had a couple of shillings in the house and that was it.

Seibert decided to bargain. “Mother, you give him a few pounds, and I’ll pay the remainder weekly.” And to the constable, “I would have told you about the money at first, but my mother and father would beat me, they would have taken an axe to me.” Charming.

Margretha was distressed and offered her few shillings to Constable Cahill if he would not take her in charge, but she was arrested on suspicion of receiving Seibert’s stolen money.

The following day, the Police withdrew the charge against Margaret, telling the Court that it was clear that she had only offered the few shillings she had because she had a newborn baby and feared being taken into custody.

Seibert was not so lucky. His parents gave the Court a picture of trying to raise an uncontrollable child. The Police Magistrate decided that 3 months in Brisbane Gaol, followed by 2 years at the Reformatory Hulk Proserpine would be the solution to their problem.

To spare the 11-year-old the terrors of Petrie Terrace Gaol, Seibert was deposited on board the Proserpine on 05 August 1872, and this was his home for 2 years, give or take a couple of weeks on dry land in March 1872. On arrival, he was 4 feet, 6 ¾ inches tall, 78 pounds with red hair and grey eyes.

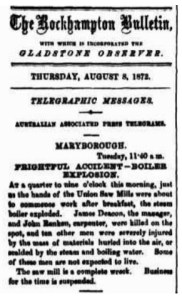

Three days later, as Johannes Ammenhauser and his mates at the Union Saw Mill sat smoking and yarning, waiting for the start-work whistle, the mill’s massive boiler exploded, sending boiling hot steam and chunks of iron, wood and brick all over them. The chimney at the mill collapsed immediately, with the sound of the explosion and collapse heard all over town. A pall of scalding steam obscured what little remained of the Union Mill.

The manager, James Deacon, was killed instantly. The man who had been nearest him, John Rankin, died moments later.

Dozens of volunteers from the wharves and surrounding areas rushed to the scene to shift rubble and try and find survivors. Distressed wives and families of Union Mill workers started to arrive, just as the gravely ill survivors were being carried off to hospital. The workers, including Johannes, had suffered devastating scalds and shrapnel injuries.

Another four men died in the hospital – including Johannes Ammenhauser, who had sustained a severe neck wound. The Relief Fund estimated that they had provided for 11 wives (6 of whom were widows), one man convalescing at home, and 32 children. Margretha’s life was suddenly much harder, and she no longer had her oldest child to help her.

On 28 July 1874, Seibert was finally released from the Proserpine, aged nearly 14. He returned to his home in Maryborough, to his widowed mother and young siblings. He worked as a labourer about the district, and, perhaps tired of spelling his name out to his workmates, insisted that they call him Jack.

On 14 August 1882, “Jack” Ammenhauser was working for Edward Lowry, part of a crew felling trees and loading log timber onto a punt. He seemed alright at first, keeping pace with the other men.

Later in the day, he mentioned feeling awful. He had a heavy cold, pain in his back, and a terrible pain in his abdomen. He worked on the following day until about 11:30 am, when he felt “awful bad”, and said that there was pain and swelling in the groin. He said he’d had the pain before, as a boy in Brisbane (on board the Proserpine), and had gone to hospital.

His employer, Mr Lowry, came down to the site and saw Jack Ammenhauser lying on a bunk in agony. He took Jack by boat to town and implored him to see a Doctor or a chemist. Jack preferred to go home to his mother’s farm, so Mr Lowry, worried and unusually kindly for a 19th century boss, put the man in a cab and directed the driver to take Jack home.

Seibert Ammenhauser passed away at his mother’s farm at Salt Water Creek on 17 August 1882. A Coroner’s Inquest found that he had died of “strain or other internal injury” incurred when loading log timber. He was 22 years old.