It all began with a handkerchief.

“On the 28th of September, between twelve and one o’clock in the day, I was in Wardour-street, Soho, something drew my attention to my pocket, and I missed my handkerchief. I saw the prisoner and another boy in front, and saw the prisoner tucking my handkerchief under his jacket. I collared him and took it from him. I gave him in charge.” James Cadwallader Parker.

The prisoner was a 15-year-old boy named Henry Drummond, and it was his first offence. The hanky in question was worth 2 shillings, and Parker was not deprived of it for more than a few seconds.

On 26 October 1821 Henry Drummond was sentenced by Lord Chief Justice Abbot to transportation to New South Wales for fourteen years.

Henry’s journey to the other side of the world was delayed by a Home Office Petition made by Charles Hawkins, who had known him since childhood. Hawkins pleaded for the lad to be released into his care, due to Henry’s youth and previous good character. The crime had been committed “through sheer want and hunger,” and Henry, an apprentice, had been driven out into the streets by a master that treated him cruelly. A position in the Merchant Navy could be secured for the boy, if only the Home Office would grant the petition.

The Home Office would not.

So began Henry’s life of crime, one that escalated from pocket-picking to piracy to mutiny and to the gallows in only thirteen years.

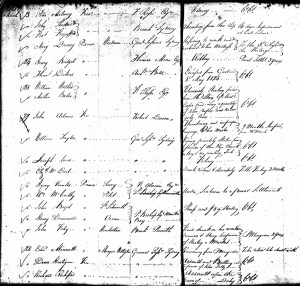

Henry boarded the Hulk Leviathan, in company with offenders ranging from children of ten years of age to hardened criminals of forty-six , and awaited his transportation to New South Wales, which took place on board the “Ocean” in 1823. Henry Drummond rounded out his teens as a working prisoner of the crown in New South Wales.

In June 1825, Henry decided to steal a piece of corded dimity from a dray in George Street, Sydney, and managed to be seen doing it. This new piece of fabric earned him a ticket to Moreton Bay for three years. His record at Moreton Bay shows that when he arrived there at age seventeen, he stood at five feet, five inches and had a fair complexion, with dark hair and grey eyes.

A Brief Stay at the Bay

The Moreton Bay penal Colony was in the process of being moved from the bayside to its present location at Brisbane. Convicts were engaged in clearing the land and constructing buildings, as well as trying to grow crops. Stores were scarce, buildings were ramshackle, and morale was low. The Sydney papers reported smugly that the progress of the settlement was being delayed by the disinclination of convicts to work hard and recommended harsher treatment.

Many of the first convicts were volunteers, prepared to work at building the settlement, hoping to receive remissions on their original sentences. Others, like young Henry, had reoffended. The only solution to the years of hard work and misery lay in escape, but this was dangerous. The convicts did not know the countryside, and were not sure of the Moreton Bay aboriginals. Would they be helped in their escape, or returned to the Commandant for a reward?

In October 1825, William Smith, John Welch and John Longbottom absconded together, there being a little more safety in numbers. They appeared to have succeeded, as they were not brought in staving and exhausted. Impressed, Henry Drummond and John Boyd followed suit on November 13 1825, taking some sheep with them in order to have a guaranteed food supply. Commandant Captain Bishop, backed up by soldiers and constables, chased the fugitives for some time, but eventually lost track of them.

By January 1826, news reached Moreton Bay that Smith, Welch and Longbottom had appeared at Port Macquarie. His Excellency the Governor was pleased to return Smith and Longbottom to the tropics, while Welch found himself on other charges in Sydney.

Drummond’s first death sentence.

In the same month, Henry Drummond and John Boyd were caught trying refresh their food supplies by stealing a few more sheep from the settlement. The two men appeared before the Commandant at Moreton Bay and pleaded not guilty in order to escape the lash and get to Sydney for a fair trial. What they probably did not expect was the severity of the sentence the Sydney Bench imposed. Death.

Fortunately for the two men, they received a reprieve a month later. Unfortunately, the reprieve meant that they would be sent to Norfolk Island for life.

Norfolk Island and the Brig Wellington

Norfolk Island was intended as a penal settlement of last resort. A prisoner could be returned from Port Macquarie or Moreton Bay, but could not expect to re-join society once he or she had been sentenced to that place.

Norfolk Island is located some 1400 kilometers from the eastern coast of Australia, and roughly in between New Caledonia and New Zealand. It was a remote and unforgiving location, uninhabited at the time of its discovery. A penal settlement had run there from 1788 to 1814 but was abandoned due largely to the impractical location for shipping and supplies.

In 1825, the convict settlement was reopened, its remoteness now recommended it as a suitable place for twice-convicted felons. Good luck absconding from there. The reprieved men from the Sydney assizes were taken off the hulk in December 1826 and were due to arrive at Norfolk in January 1827.

The prospect of Norfolk Island terrified the prisoners ordered to board the brig Wellington, to the extent that a group of them seized control of the brig on the day it was due to arrive, and sailed it towards New Zealand. Henry Drummond, not yet twenty, was one of the pirates. It was a long way from nicking a hanky in Soho.

Unfortunately for the convict pirates and their dreams of freedom, a whaler under the command of the heroic-sounding Captain Duke was at anchor off the Bay of Islands. A skirmish ensued, lasting about six hours, and two convict pirates were killed.

Duke had several hundred Maori men at his disposal and issued the threat that if the outlaws did not surrender, he and his crew would “bear down on them” and “hunt them all to death.” Naturally, no-one wanted to be disposed of in such a manner, and a hasty surrender was effected.

In the aftermath, as Duke was flogging the captured pirates, Henry Drummond and his running-mate John Boyd, broke down and confessed the whole dastardly plan. The contrite pair had to be kept separate from the other captives on their way back to Sydney, for fear of being slaughtered by their fellow pirates for snitching.

[There is a wonderful contemporary account of the skirmish that ended the pirates’ run to freedom on the Wellington, borrowing heavily from a ship’s log. I will publish it verbatim as a separate post.]

In February 1827, the Supreme Court of New South Wales, duly vested in the Vice Admiralty jurisdiction, and chock full of fascinated spectators, dealt with the Wellington Pirates. I imagine the spectators became rather less fascinated as the arguments before the Court moved to the vexed subject of jurisdiction and procedure. A lengthy ruling was at last made, and the trial spread over several days.

Henry Drummond was found guilty and sentenced to death for the second time in twelve months. He must have regretted the flit from Moreton Bay that turned him from a youth who purloined small quantities of fabric to a twice-condemned felon.

Norfolk Island Rebellion

Fortune smiled on Drummond once more, inasmuch as his life was again spared. He would spend the rest of it on Norfolk Island.

Little was heard from that settlement, beyond official notifications about the comings and goings of felons and Commandants, so it came as a shock to mainlanders to read the news of a mutiny at the Settlement on 15 January 1834.

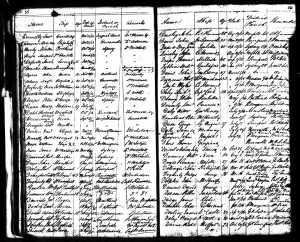

Captain Foster Fyans, Commandant of Norfolk Island, and future Commandant of Moreton Bay, sent a dispatch to His Excellency, reporting a convict mutiny that resulted in five convict deaths, and ten wounded. One of the wounded was Henry Drummond, who was later charged with aiding and abetting the ringleader convict, Robert Douglass.

The Supreme Court convened on Norfolk Island to try the mutineers, with Judge Burton presiding. A jury of seven military men was empaneled, and the trial, with extensive eye-witness evidence lasted over several days. Any convict who entertained hopes of a “fair trial,” not to mention escape opportunities, in Sydney was disappointed.

For information about the trial, I recommend the report of R. v. Walton et al. [1827] NSW Sup C 7; which can be found at the Macquarie University website, Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788-1899. http://law.mq.edu.au/research/colonial_case_law/nsw/cases/case_index/1827/r_v_walton_et_al/

The mutineers were found guilty and sentenced to death. On this third occasion, Henry Drummond did not escape his fate. He was executed by hanging at Norfolk Island on 22 September 1834, and is buried in the cemetery at the settlement.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported:

Henry Drummond.

“Thirteen desperate men have been executed, pursuant to the sentence of the court lately held on the island; and, as we are informed, died penitent. Their names were Robert Douglas, Henry Drummond, James Bell, Joseph Buller, Robert Glennie, Walter Burke, Joseph Snell, Michael Andrews, William Groves, Henry Knowles, Thomas Freshwater, Robert Ryan, and William McCullock They received the spiritual attendance of the Rev. Mr. STYLES and the Rev. Mr. Ullathorne, according to their respective religious persuasions.

“Thus have thirteen more human lives been sacrificed to the Moloch-Vengeance, which dooms men to scenes of horror like that of Norfolk Island. True, these wretched men were, as all others similarly circumstanced on the island are, degraded as low as human beings can be degraded-they well deserved to be cut off from all chances of association with their kind-but are there not modes of punishment to be adopted which will not lead to the commission of still greater crimes than those for which they have been doomed to banishment? If men are thought worthy to live, why reduce them to a state to avoid which they court death, and in order to ensure the last dread punishment which man can indict, commit new and still more fearful crimes? This is the natural consequence of the unnatural system pursued at Norfolk Island-a system which, so long as it is persevered in, will tend only to multiply crime, and to provide occupation for the executioner. Even in the present instance, the authorities have been obliged to take measures to prevent new murders. Six men belonging to the gaol-gang at Norfolk Island, who were chiefly instrumental in preventing the intended revolt of all the prisoners there, by giving timely information of the conspiracy, have been brought up to Sydney, for safety; and such is the deadly hatred entertained against the whole of the gang to which these men belonged, that we shall not be surprised if, in a very short time, there is a necessity for another special commission and more hanging. It is, we understand, the intention of the government to break up the penal establishment at Moreton Bay, should the measure receive the sanction of the Secretary of State; we hope it will be followed by an alteration in the inhuman system upon which Norfolk Island is maintained.”

Thirteen years earlier a starving fifteen-year-old boy took a handkerchief from a man’s pocket. For that, he was imprisoned with hardened criminals, and sent to the other side of the world, where he gradually increased his offending, which was mostly motivated by desperation. At the age of twenty-eight, he was executed.

The headstone incorrectly states his age as 26.

It is tempting to wonder what kind of life the teenager might have had if he had not nicked the handkerchief or had at least been dealt with by a sane legal system for a trivial first offence. The petition of Charles Hawkins makes for wistful reading. Henry would have had a home, food, care and a good job. The Home Office said no.

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thank you However I’m experiencing difficulty with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting similar rss problem? Anyone who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

LikeLike