A Piratical seizure, a journey to the south seas, a court martial and a decades-long international manhunt.

In December 1853, the last of the Norfolk Island Pirates, already under sentence for their misdeeds in Moreton Bay, faced the Court at Hobart Town and pleaded guilty to stealing the launch at Norfolk Island. Property of Her Majesty the Queen, and valued at £50, if you don’t mind.

The sentences imposed were suitably heavy, and all nine of the original Norfolk Island runaways were promised the distinct pleasure of a return cruise to Norfolk Island, along with an assortment of Tasmania’s most colourful recidivists of 1853.

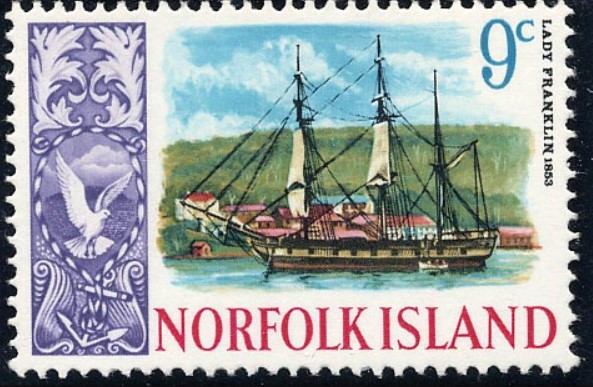

Their transport to that place was the barque Lady Franklin, named in honour of the beloved and philanthropic wife of the former Lieutenant-Governor of Tasmania, Sir John Franklin.[1]

Under the command of Captain Willetts, the Lady Franklin left Hobart on 10 December 1853. Her crew included soldiers of the 99th Regiment, and the prisoners were locked in cells within in the hold, where they would be safe and secure for the voyage.

The Prisoners on the Lady Franklin

The prisoners included James Quinn, a 30-year-old shoemaker from Newcastle, transported in July 1844, and sentenced in October 1853 at Hobart for highway robbery, along with his co-accused, Charles Brewer, a Londoner who’d been in Van Diemen’s Land for over 15 years, and John Twitty, a heavily tattooed blacksmith from Birmingham. Quinn and Brewer had their death sentences commuted, largely due to Quinn’s almost courtly politeness towards the man they robbed.

Thomas Williams, Andrew Duff and Patrick Hickey were also co-accused, and had just escaped the noose in Hobart for cutting and wounding, an incident that the Launceston Examiner said, “appears to have originated in one of those disgraceful drinking rows which have become so prevalent here.”

James Neal, relatively new to the Colonies and still under his original sentence, mixed with an old desperado from Glasgow, Robert McKinley, who had been transported before Neal was born. Then there were the convicts who couldn’t blend in easily if they tried to go on the run – Richard Walton, with his speech impediment, Thomas Brown with his distinctive tiny grey eyes, Edward Dowdall with his pointed nose and scar over his eye, James Ford who had cupping marks all over his torso, and Joseph McKenzie with his heavily scarred hands.

And of course, the Moreton Bay Nine. Robert Mitchell, Dennis Griffith and James Clegg, who were captured early in the crime spree on Stradbroke Island after the theft of Fernando Gonzales’s boat and returned to Van Diemen’s Land, were on board.

They were joined by the six men who had captured the Harbour Master’s boat, nicked the crew’s uniforms, and robbed the Pilot of all of his portable possessions, before finally shooting at one of his children for good measure. They were John Meek (or Mick), Thomas Clayton (or Claydon), John Sillifant (or Edward Sullivan), Joseph Davies, Joseph Cooper, and James Merry.

Bound for Norfolk Island

None of these men wanted to go to Norfolk Island, particularly those who were about to sample its bracing airs for a second time. Some were “desperate characters,” all for a mutiny, as bloody and disruptive as possible. The ringleaders of the mutiny and the desperate characters group were James Quinn, Charles Brewer, James Neal and John Twitty.

Some were not interested in plotting and thus were not made aware of the exact plans to take the vessel. James Merry and Joseph Davis were in this group. The idea of liberty was appealing, but not the death part.

The ringleaders came up with an audacious plan. They would cut a hole in the decking of their cell to create a passage that would lead to the upper deck. At this point they would liberate the prisoners from the other cells. From there, the mutineers would take weapons from the hold and use them to overpower the Captain, crew and guards. They would take the vessel to a place that was presently known as the Feejee Islands, and from there – freedom and mischief.

Powerhouse Museum.

Due to a bizarre set of coincidences, the plan worked beautifully. The deck between the cells and the aft was only two inches thick. The pirates even had a tool at hand for cutting the thin gumwood deck – the handle had broken off a pannikin. There were unsecured firearms in the hold and up for grabs, but they were old and useless. Nobody on board knew that they didn’t work.

At 2 am on 28 December 1853, the prisoners took control of the vessel, precisely as planned. The attendant scuffle woke Captain Willetts, who found himself under physical attack and no longer in command.

The ringleaders of the mutineers wanted to murder the entire crew of the Lady Franklin, starting with the Captain. One of their number, possibly James Neal, famously offered to “be butcher.” Two members of the Moreton Bay Nine, James Merry and Joseph Davis, called for calm heads. In so doing, they saved Captain Willett’s life and averted a massacre. Willetts was quite badly hurt, suffering a broken collarbone, broken teeth and cuts to the head from a cutlass. Davies dressed the Captain’s wounds, and was tasked with guarding him, which he did with kindness.

An old-fashioned piratical parley took place between the pirates and the men of the 99th Regiment after some initial rough and tumble. The soldiers agreed to hand over their own firearms and take to the lower hold, in return for no further rough and tumble. And no shooting please. The coup was so convincingly executed that no-one had discovered that the weapons from the hold didn’t fire.

Ahoy there?

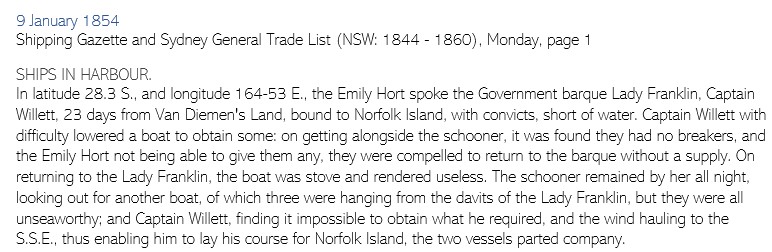

Well, that was odd. Buried deep in the shipping reports from early January 1854 was a report of an awkward marine rendezvous between the Lady Franklin and the Emily Hort on 06 January 1854. The Lady Franklin had been well-provisioned on departure, and now she was out of water and all of her boats were suddenly unseaworthy?

Unbeknownst to the crew of the Emily Hort, the prisoners had taken over the prison ship, and Captain Willetts was acting under duress. In fact, the approach to the other vessel had been made with a view to seizing her and butchering her crew.

The pirate ringleaders asked Captain Willetts to assess their chances of taking the Emily Hort; he refused to provide advice that would lead to the injury of others. Once again, Davies intervened for the safety of the Captain, who had committed the grave error of not telling armed pirates what they wanted to hear.

Two days later, on 08 January 1854, the mutineers decided to load the Lady Franklin’s longboat and cutter with provisions, and take to the seas. Two convicts were left on board the Lady Franklin, James Neal and Edward Dowdall. Rejected by their fellow convicts, they could only hope to be treated mercifully by the Courts.

Before quitting the Lady Franklin, the convict pirates thoughtfully damaged her rigging and sails, just enough to slow her, and to ensure that she could not chase them about the South Seas. Those still on the loose were: James Quinn, Charles Brewer, John Twitty, Thomas Williams, Patrick Hickey, Andrew Duff, James Ford, Joseph McKenzie, Robert McKinlay, Richard Walton, Thomas Brown, Robert Mitchell, Denis Griffiths, John Meek/Mick, James Clegg, Joseph Davis, Thomas Clayton/Claydon, Joseph Cooper, Edward Sullivan/Sillifant and James Merry.

A Trial and a Court-Martial

There was a non-commissioned officer’s guard on board, who from the circumstances do not appear to have behaved very gallantly upon the occasion.

Hobart Courier, 27 January 1854.

Having decided that it was too difficult to continue to Norfolk Island with the damaged rigging, Captain Willetts turned towards Van Diemen’s Land, arriving at Spring Bay on 18 January 1854, then Hobart on the 28th with two prisoners and a suitably deflated crew. The first newspaper account of the seizure had been provided to an aghast Van Diemen’s Land public the day before.

Captain Willetts received medical treatment and was hailed for his courage. James Neal and Edward Dowdall were put in heavy irons to await trial. The civilian crew disembarked, but the soldiers remained on board.

After months of adjournments to locate witnesses, James Neal and Edward Dowdall were found not guilty of cutting and wounding on board the Lady Franklin by the Supreme Court at Hobart on Thursday April 20 1854. They were returned to Gaol to continue serving their already lengthy sentences.

The soldiers of the 99th Regiment remained on the Lady Franklin, where an internal military investigation took place, which terminated on February 16 1854. Three soldiers were recommended for Court Martial. These men, Sergeant Allen, Private Michael Durr and Private O’Keefe had been on guard duty on the night that the prisoners took over the ship.

We are quite aware that the Board sat with closed doors but as the question is one of very great importance, the public, in our opinion, are entitled to the fullest information on the subject.

The Tasmanian Colonist on the protracted military investigation.

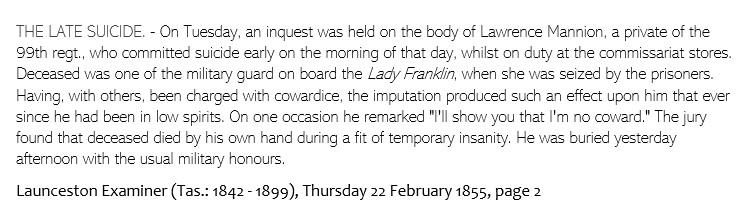

The Court Martial of the three soldiers who had been on duty on the barque finally came to an end with sentencing in April 1854. Sergeant Allen was reduced to the rank of private soldier (with a strong recommendation to be released immediately from arrest and restored to his previous station), Private Michael Durr was found guilty and transported for life, and Private O’Keefe was honourably exonerated. Although only three of their number were tried, all of the soldiers who had been on board the Lady Franklin felt their reputations had been tainted by accusations of cowardice.

The Pursuit Through the Islands

Nothing was heard about the convict pirates from the Lady Franklin for some time. Perhaps they had perished in their stolen longboat and cutter in the rough seas. Perhaps they were pillaging some remote islands. They seemed long lost.

In July of 1854, the steamer Torch was reported to be heading for the Fiji Islands to seek out the convict pirates. The commander of that vessel had heard rumours that the villains were committing depredations on one of the islands, and was determined to bring the blackguards to justice. Back in Hobart, the public shivered as it steeled itself for a tale of bloodshed to ensue. Fortunately, it didn’t ensue.

After months of silence, a report suddenly appeared in the Australian papers at the end of December 1854 that three of the convict pirates had been captured and were being forwarded to Sydney aboard the survey ship HMS Herald.

By January 3 1855, it became clear who the convicts were, and what they had been up to all year. The pirates on board the HMS Herald were James Merry, Denis Griffiths and Joseph Davies.

There followed dramatic reports in some newspapers of the convict pirates seizing a Dutch schooner and murdering everyone on board, and of depredations about the Islands of Fiji. Once the two captured convicts were back in Australia and the officers of the Herald were able to give evidence in Court, a clearer picture emerged.

On 16 October 1854, James Merry had gone to John Hutchinson, Lieutenant of HMS Herald at Ovalau, Fiji, identified himself as an escaped convict and surrendered. He gave Hutchinson his entire story, starting at Newgate, and ending with his piratical activities:

After taking the boats from the Lady Franklin, the convicts made land on the Fiji Islands and the large group gradually split up. James Merry, Joseph Davies and Denis Griffiths, stayed together on Viti Levu, the big island. They seem to have taken Fijian women as their partners, and did odd jobs about the place.

Once Merry had given himself up, Lt Hutchinson was able to locate and capture Davies and Griffiths. On board the Herald, Denis Griffiths had loosened his chains and escaped again. Davies and Merry were watched closely on the return journey to Sydney.

On hearing the evidence of Lt. Hutchinson, the Sydney Bench ordered Merry and Davis to be transported back to Van Diemen’s Land for trial.

Van Diemen’s Land – misery, redemption and blame

In the year following the seizure of the Lady Franklin, the fortunes of those involved varied wildly. Private Mannion saw no way out of the shame of the military inquiry, Sergeant Allen was restored to his prior station, two convicts faced death, and the Government faced the cost of the hijack.

In June 1855, the Supreme Court at Hobart heard the trial of Joseph Davies and James Merry. If the public gallery, and indeed the Court, had been expecting to hear a lot of evidence about brutal piracy and depredations and slaughter in the South Pacific, they were disappointed.

They heard the evidence of Sergeant Allen and Captain Willetts, that following the audacious act of piracy by the prisoner group, Davies and Merry acted with remarkable kindness to their hostages. The two men seemed to act as a human shield between the more violent pirates and their captives. Captain Willetts quoted Joseph Davies as saying, “Don’t be at all alarmed at anything you shall hear, for I am determined that the promise made to you shall be kept, and I think I am strong enough to keep them to it.”

Eventually, the jury found the two men guilty, which meant the death sentence, but recommended them to mercy. The Judge assured them that their pleas would be brought to the attention of the correct people.

“Merry and Davis who, it will be in the recollection of our readers, were the only prisoners captured for the piracy of the Lady Franklin, are now in the service of the Puisne Judge, Mr. Horne. Sentence of death had been passed on them, but through this gentleman’s intercession, it was commuted to six months’ imprisonment with hard labor at Port Arthur. It was through their determined character and power over the other pirates that the lives of Captain Willett and the crew of the Franklin, as also of the officers and soldiers, on board were saved. Merry and Davis behaved themselves in an exemplary manner at Port Arthur, and on their discharge to Judge Horne’s service from the Penitentiary, expressed their determination to amend their lives; and we doubt not but in a short period they will have recovered much of their lost characters. They have the good example of Martin Cash before their eyes.“

Hobarton Mercury (Tas.: 1854 – 1857), Wednesday, 19 December 1855 page 2

LIABILITY OF THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT. A dispatch has been received from the Secretary of State, complying with the recommendation of governor Sir W. T. Denison, that the parties who had suffered by the plunder and piracy of the Lady Franklin at Norfolk Island in December 1853 by Griffiths, Davies and others, should be indemnified for the loss, they had sustained. In consequence of this compliance, orders are now payable at the Commissariat in Hobart Town for the full amount of the respective claims.

Hobarton Mercury, 25 June 1856.

The Search for the Others

The search for the remaining eighteen runaway convict pirates continued over the years, the enthusiasm of the authorities gradually decreasing as the years passed.

On 30 April 1855, the Sydney Morning Herald announced that two of the Lady Franklin pirates had been apprehended and brought into Sydney by Inspector Singleton to be charged. Their names were James Hamilton and Jesse Show.

On 09 May 1855, the Sydney Morning Herald announced that James Hamilton and Jesse Show had been released without charge, after Inspector Singleton consulted a copy of the Hobart Town Gazette that contained the names and descriptions of the pirates.

In August 1859, a man named David Haydon was apprehended in New Zealand and transported to Hobart to face charges of piracy relating to the Lady Franklin. Private Dennis O’Keefe of the 99th Regiment swore to Haydon’s identity as one of the pirates.

David Haydon was able to prove that he was not involved in the piratical acts, because he was in custody at the penitentiary at Hobart at the time of the Lady Franklin affair. Haydon had served his sentence and gone on to live and work in New Zealand, where he had land and a family.

O’Keefe was upbraided for at the very least holding on to a misidentification, if not actually perjuring himself. Members of the Police and public took up an urgent collection to return David Haydon back to New Zealand and his family.

For Haydon, the worst part of being wrongly accused was the sea journey to Van Diemen’s Land. The crew of the ship that took him there had treated him with contempt and hostility, believing him to be a mutineer.

Sullivan the Murderer

In March 1875, newspaper reports claimed that Joseph Thomas Sullivan, notorious for his involvement in a mass murder in New Zealand in 1866[2], was one of the Lady Franklin convicts. Sullivan had served a term of imprisonment in New Zealand and had travelled to England and Australia in the 1870s. The story quoted a witness as being “morally certain” that the Sullivan and Kelly on board the Lady Franklin were the same as those involved in the Maungatapu murders a decade later.

There was no Kelly on board the Lady Franklin and the Sullivan on that ship was John Sillifant alias Edward Sullivan, who sported a distinctive facial scar that was not present in the description of Joseph Thomas Sullivan. Joseph Thomas Sullivan had established a family in Melbourne prior to the murders, at the time when Sillifant/Sullivan was at large in the Islands.

Au Revoir

In the ensuing decades, there would be rumblings and rumours, but nothing definitive on the rest of the pirates. A rambling, entertaining article on the Lady Franklin by “the Vet” – for Veteran I presume – in 1895 mixes dates, personnel and stories with promiscuous glee, and the link below can save you the search. If you’re game.

17 Aug 1895 – AU REVOIR. – Trove (nla.gov.au)

[1] (At the time, Lady Franklin herself was almost a decade into her gallant, life-long search for her husband, who had disappeared on an expedition to the North-West Passage in 1845.)

[2] The Maungatapu murders, in 1866. Joseph Thomas Sullivan was granted immunity from the death penalty for his involvement in the killing of five people on Maungatapu track. His three co-accused were convicted and subsequently executed.

SOURCES: