In the late 1840s, colony of Moreton Bay and its surrounding districts had been open to free settlers for several years, but was struggling with the need for labour, institutions and infrastructure. The convict buildings left about the place had deteriorated, and there was little economic stimulus to create new facilities for the town.

The rural settlers who were determined to make the most of the vast and fertile land they had filched from indigenous people needed workers to manage crops, flocks and herds. Needless to say, they wanted them to be cheap.

Grey’s Convict Exiles

At the same time, the United Kingdom had more convicts than it knew what to do with (again!), and this gave a chap named Earl Grey a rather splendid idea. Rather than address the causes of crime, sentencing or prison reform, he decided on a convict exile scheme. Prisoners who had served a portion of their sentence would be transported to Australia and given a ticket of leave on arrival, permitting them to work for wages.

The overcrowding in prisons and hulks would decrease, and the United Kingdom would be shot of a few thousand felons permanently. Free settlers – particularly those in rural areas – could employ ticket of leave convicts at a knockdown rate.

In Australia, this news was greeted with dismay from those who had hoped that the convict years were over, resignation from the authorities who would be tasked with dealing with the new system, and unfettered delight from those seeking to hire labourers.

After this we should not be astonished to hear that the colonists had chartered ships for the purpose of emptying the gaols of the United Kingdom.

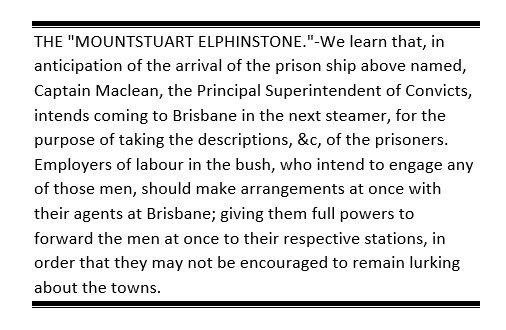

The Moreton Bay Courier, 03 November 1849

Lang’s Cooksland

Coincidentally, another public figure had a splendid idea to deal with the Moreton Bay labour shortage, and it would be greatly at odds with the plans of Earl Grey, the British and Colonial Governments.

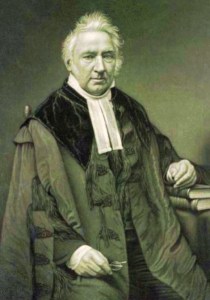

The Reverend John Dunmore Lang was an old Colonist, who, when not disapproving of things like fancy dress balls, Sabbath picnicking and alcohol, advocated for skilled British immigration to Australia. He had a particular vision for the vast area of New South Wales that lay to the north of Moreton Bay. He would call it Cooksland, and populate it with skilled, morally sound, hardworking protestants from the old country.

The indefatigable Doctor set about recruiting – personally – potential immigrants of this persuasion, and encouraged them to think of themselves as pioneers of a new Australia. People whose industry and sobriety would cleanse the new country of its convict taint.

Unfortunately, Dr Lang had a combative relationship with those actually in charge of the colony and its immigration (the Colonial Secretary in particular), and as a result, the authorities had no interest in sanctioning whatever the dashed fellow was up to.

Already one official British emigrant ship, Artemisia, had arrived in Moreton Bay in December 1848, bringing 89 females and 120 males to Brisbane. One of the females was the future Anna Maria Powell, a woman of boisterous and intemperate habits, who styled herself the Queen of the Artemisia. She may not have contributed much to the Colony, but she kept court reporters entertained for nearly 20 years.

The first of the Cooksland ships was the Fortitude, a barque constructed in 1842, which housed the 252 immigrants intent on bettering their own lives and the Colony while they were at it. She arrived at Moreton Bay on 21 January 1849. Dr Lang had already given the Moreton Bay Courier a warning that the immigrants would be relying on the, er, assistance of other settlers because of the whole awkwardness with the British Government thing. After some official dithering, the immigrants were permitted to form a temporary village near York’s Hollow, which in time became known as Fortitude Valley.

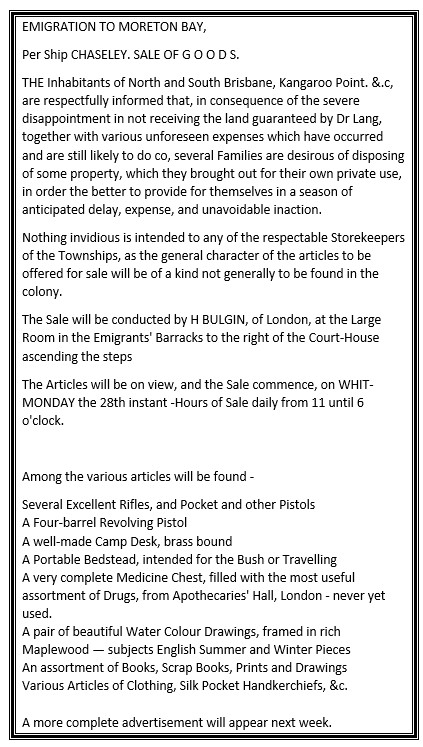

When the Chasely arrived in the first week of May 1849, the Brisbane authorities were better prepared for the second lot of Lang’s Immigrants. The old Barracks Building had been withdrawn from sale and was pressed into service housing the fresh wave of nation-builders. There were no private dwellings to be had in Brisbane Town at that time. That would be the least of their problems.

Questions – posed in the most respectful manner – began to appear in the press about the organization of the Cooksland immigration, and the undertakings made by Lang. The colony’s Immigration Agent offered what assistance he could on both occasions, although the Cooksland immigrants were not strictly in his jurisdiction.

While hundreds of Lang’s immigrants were dealing with the hardships of starting life in a new country on somewhat different terms than expected, the Tamar brought 45 ticket of leave men from Sydney, where they had been disembarked from the Randolph and the Hashemy.

A Return to Transportation.

According to J.J. Knight in the Queenslander in 1892, residents of Brisbane Town noticed “incipient signs of rowdiness” following the arrival of the first convict exiles in June 1849. There isn’t much documentary evidence of a sudden lapse of public order, but then the groups of labourers were relatively small.

The main offender was one George Muir, late of the Hashemy, who decided that it was time to sample the local drinking establishments, and became combative when approached by Constable Beardmore. Forty-eight hours in the cells on bread and water sorted his hangover out.

Graziers and squatters pounced on the convict exiles and waited eagerly on news of the next shipment. No-one anticipated Earl Grey’s next move.

An Exclusive Penal Colony

Earl Grey is reported to have said that in order to put an end to all objections that might be made to the reception of convicts by the elder colonies, Moreton Bay would be declared a place to which transported offenders might be sent and would be severed from New South Wales for that purpose

Moreton Bay Courier, 01 September 1849

The capital idea of convict exiles had been canvassed throughout the Colonies of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. Unsurprisingly, those places that had played host to transportation in the past objected to its resumption. (Moreton Bay had been a place of secondary transportation when it was a penal colony, and had no experience of large convict transports arriving.)

Indeed, the objections from former convict settlements were so strong that Earl Grey had another idea. In September, the news reached the Moreton Bay Courier that the Home Secretary had decided to make Moreton Bay a penal colony again, and in fact the only penal colony in Australia for convict exiles. Brisbane Town and surrounds would be separated from the rest of New South Wales for the purpose of transportation. This news was unwelcome to most, except our old friends in the bush, who still needed labourers.

As this grim news was sinking in, the Mountstuart Elphinstone was on its way, and arrangements had to be made for the reception and dispersal of 230 ticket of leave exiles. The Lima was due at the same time, with more Lang immigrants.

There goes the neighbourhood!

The transport Mountstuart Elphinstone arrived at the Bay on 01 November 1849 to the usual rapturous reception from bush settlers and their town agents. Those prisoners not engaged immediately, or at least secured by their employers immediately, made quite an impression.

We wish we could speak as favourably of their conduct as of their health. During the time that they remained in Brisbane the place was completely in an uproar. It was impossible for our miserably slender police to keep them in order, and this day’s publication records a few of the consequences.

The Moreton Bay Courier, 10 November 1849.

The Anti-Transportation Movement

Well, that was frankly quite enough. It was bad enough to become a penal colony again, and be separated from the rest of New South Wales, but disorder on the streets? A meeting would have to be held.

That occurred on 13 November 1849 at the Immigration Office. Mr Coley was pressed into service to chair. The meeting was called, he said, to determine the best way of dealing with the exiles, now that that “such persons would be sent hither.” There was no longer any question of the Home Government’s intention, therefore Moreton Bay requested an increase in troops and Police in response. The chair’s resolution read:

“That, as it appears highly probable that the Home Government intend to send out huge bodies of exiles to this district, this meeting petition the Queen and both Houses of Parliament not to send them out unless accompanied by corresponding military and police establishments, and by an equal number of reputable emigrants.”

Just as the motion was put forward for the vote, Mr Richard Jones seized the moment. He spoke passionately of the evils of the convict system, compared the sacrifices that the Cooksland immigrants had made with welcome for the Mountstuart Elphinstone exiles, and declared that many who had travelled to the colony did so on the understanding that it would be a place for free settlers. (Every point was greeted with wild applause.) He proposed his own resolution:

“That, whilst we admit that there is a great want of labour in this part of the colony, there are no terms, however favourable, that the Imperial Government could offer us, that would induce us, with our own consent, to receive convicts to be transported from the mother country to this part of the colony.”

Jones’ proposal was met with cheers and promptly carried, and the Mr Coley vacated the chair for him. Petitions were requested, committees formed and meetings called. It was unusually business-like for sleepy little Brisbane Town.

The Bangalore and The Emigrant

After an exhausting 1849 spent dealing with poorly planned skilled immigration programs and convict exiles, Brisbane waited until May 1850 for the next direct shipment of ticket of leave convicts. The Bangalore was met by authorities who were by now practiced in organising the arrival of hundreds of newcomers. All of the men were engaged quickly, and sent to parts rural.

The announcement by Earl Grey of the immediate removal of troops from Brisbane in June 1850 was met with open hostility. And there would be no compensation in the form of further police officers to control unruly convicts. Perhaps coincidentally, the Bangalore was the last convict exile ship to be sent specifically to Moreton Bay.

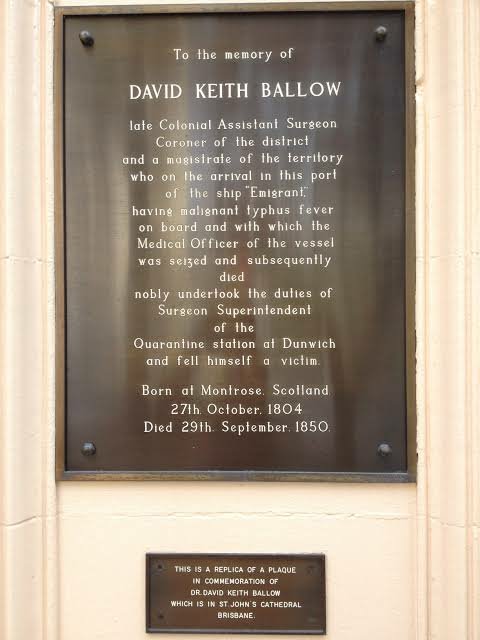

The Cooksland transports had ended with the Lima in November 1849, but Government sanctioned skilled immigration continued. In August 1850, Earl Grey’s Emigrant arrived in Moreton Bay. Tragically, her passengers had been were exposed to typhoid. In addition to the 18 who died at sea, 26 passed away at the Dunwich Quarantine Station. Dr David Ballow went out to the Quarantine Station to relieve Dr Mallon, who had become ill. Dr Ballow himself passed away from the disease himself shortly afterwards.

After the Emigrant, sadly, the health of the passengers, rather than their status or potential use to the colony, became the priority for officials.

Sources: