A survey of some early cases

Criminal sentencing is a polarising topic – it’s not harsh enough on some criminals, too harsh on others. The press and public periodically lament the judiciary’s lack of community awareness. Life means life etc.

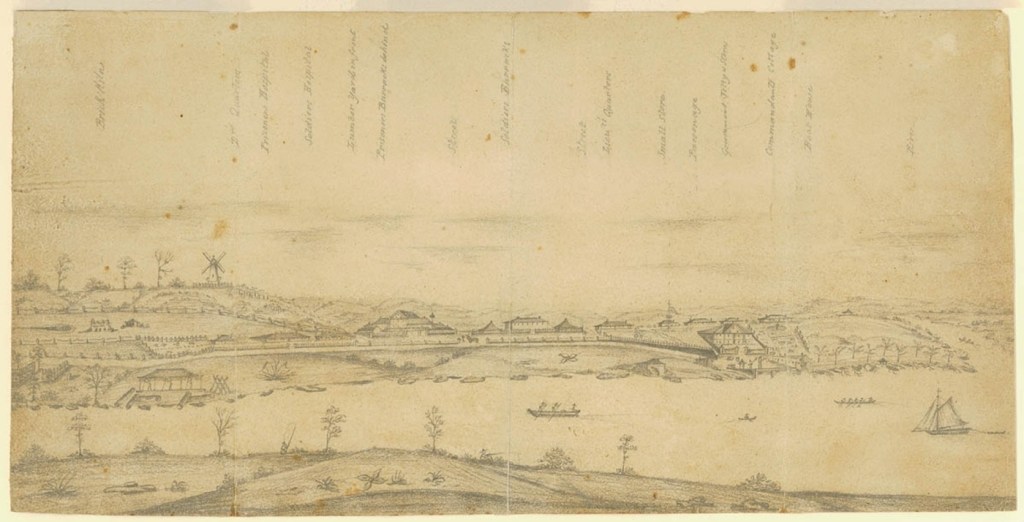

Modern Australia does not have the death penalty, but it was well and truly on the table during the turbulent 19th century. Our laws then were English laws categorised by Monarch and year, some dating back to the Middle Ages. It’s much more straightforward in Moreton Bay today.[1]

Naturally, in a society composed of serving felons, ticket of leave convicts and their settler overlords, the judiciary was dealing with a full caseload in lot of fairly peculiar circumstances. Even in this environment, some of the sentencing decisions are breathtaking.

Slight cases of murder

Hugh Mitchell was a free labourer in Sydney town, and had lived with Laura Murphy for years. Times were tough, and they argued frequently. One night Hugh got particularly violent, and Laura Murphy lost her life. Jealousy was reported to have spurred Hugh Murphy to strike Laura, and the blow was so vicious that she passed away.

“In one of their small quarrels the prisoner struck the deceased a fatal blow, which led to her death.” The Australian, 22 July 1826.

Small quarrels? Mitchell was initially charged with murder but was found guilty of manslaughter at his trial and given 3 years to Moreton Bay. Nothing about the sentence caused any unease or public comment. Man kills woman he lives with. Nothing to see here.

More outrage was expressed at the murder of Patrick McCooy by two Australian-born men. William Puckeridge and Edward Holmes were involved with two others in a late-night ambush of McCooy at the brick fields, following an assault on Puckeridge’s mother.[2]

McCooy was identified – correctly or otherwise – as the man who had ill-used his mother, so William Puckeridge knocked his victim down, and, at the vocal urging of a drunken Holmes, jumped on McCooy’s stomach several times, using his full weight. A crowd watched and cheered the attack.

“It is too much the habit of the lower orders of Natives of this Colony to revenge their own quarrels.” The Sydney Monitor, 23 March 1827.

The two men received the death sentence, then a hefty respite – 7 years at Moreton Bay. Holmes did his seven years’ hard labour, and sailed home to Sydney in 1834. Puckeridge absconded twice and found himself spending the rest of his sentence on Norfolk Island before reforming and becoming a respected community member, passing away in 1877.

You get less for murder.

You really do. Anthony Best was a well-known and successful businessman in Sydney in the early 1820s. It was wrong of him to accept stolen goods for resale, and he deserved to be punished. Unlike a person who had violently ended the life of another, he received 14 years at Norfolk Island, which was converted to 7 years at Moreton Bay when Best behaved honourably during the seizure by other convicts of the brig Wellington.

Best was 50 at the time he arrived in Moreton Bay in 1827, and this is how transportation had treated him a year later:

“One of the Crown witnesses brought up from Moreton Bay, to give evidence at the present Criminal Court Sittings, is Anthony Best, who, it will be recollected was sentenced, about eighteen months ago, to fourteen years transportation, for receiving stolen property. The appearance of Best in walking through the streets on Wednesday, on his way up to the Courthouse, was remarkably striking. Those who had seen him two years ago walking through Sydney in health and spirits, recognised the change. Best, during his “rustication,” has become so altered in appearance, that many to whom his person was not known on the above occasion, could scarcely identify him.” The Australian. 19 September 1828.

Best returned to Moreton Bay to finish his sentence and was released to Sydney in 1833, just a year before Edward Holmes (for murder). It is doubtful that the 5 further years at Moreton Bay improved his health and appearance so remarked on by his acquaintances in 1828.

It was also very wrong of Alexander William Hoyle, who was a free settler, to forge a cheque and defraud the Bank of Australia of £5, 10 shillings. It was a patently dishonest act, and £5 was a considerable sum of money for the time, over $600 in today’s money (if the various online comparison calculators I fumbled about with are to be believed).

Hoyle was sentenced to death in June 1827 for the forgery, which was commuted to 14 years at Moreton Bay. He would have been released in 1841, but his “extreme good and deserving conduct” won him a sincere recommendation to leniency by Commandant Captain Foster Fyans in 1836, and he was returned to Sydney that year.

At the same Supreme Court sittings as Hugh Mitchell, Charles Kable was found guilty of stealing one horse, and was sentenced to death. (And he might have been able to be acquitted on a technicality, had the Bench been minded to hear that argument.) Fortunately for Mr Kable, death was commuted to life at Moreton Bay. Even more fortunately, he was released in 1832.

Clearly money and property meant a great deal more than human life and safety.

Here’s a small section of comparative sentencing for prisoners sent to Moreton Bay in the late 1820s.

Admittedly, the Court calendar would beggar the belief of any modern judge. Judge Forbes was in constant poor health, and exhausted by his workload. Judge Dowling collapsed on the Bench, after years of presiding for ten and eleven hours per day, and died not long after.

The next time you shake your head at the modern judiciary, think of Laura Murphy, whose killer got 3 years at Moreton Bay. Or William Hoyle, the 5 quid forger, who was rescued from the gallows to be transported for 14 years.

[1] In modern Queensland, we have an encoded system of criminal law (rather than a mix of statutory and common law offences). The standard sentencing ranges for all offences are laid out in the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992, allowing Judges and Magistrates some discretion within its parameters. It’s a hefty read, stopping just short of 340 pages.

[2] Much gleeful copy was made of Puckeridge’s female relatives and their alleged behaviour: “The mother of Puckeridge is so drunken a woman, that she sometimes is seen lying about in the streets.” “Puckeridge’s sister, a loose woman” (Monitor). In contrast Edward Holmes’ refined and pretty young wife was stricken with grief at his sentence and occasioned much sympathy for him in The Australian.