In April 1840, a young convict servant to Mr Robert Dixon, a Surveyor at Moreton Bay, was sent to Sydney on the Cutter John. Unusually, her fare and rations were paid directly by Mr Dixon, rather than the Government. A year later, she would figure in a trial at Moreton Bay that arose from a bitter dispute between Owen Gorman, then Commandant of Moreton Bay, and Robert Dixon.

A convict named John Ford taunted Gorman about his “carryings-on” with “that infernal vagabond of a woman,” earning himself a summary trial adjudicated by Gorman himself, and 75 lashes. Within a year, Gorman would be stripped of his Magisterial powers, and Dixon would find himself removed from the public payroll.

The Woman

The infernal vagabond of a woman was Marcella Brown, who, at the time of the alleged carryings-on, twenty-four years old, 5 ft 3, with red hair, a fair complexion and grey eyes. Her arms were freckled from working in the sun, and she had a small diagonal scar over the inner corner of her left eyebrow. She could read and write, and just a couple of years earlier, she was a married woman with an infant daughter, living at King’s County.

Her life in Ireland ended when she was convicted at King’s County in 1837 for stealing money, and sentenced to be transported to Australia for 7 years. She sailed in the Diamond with 158 other convict Irish women, arriving in Sydney on the 29th of March 1838. It is unlikely that she ever saw her husband or daughter again. (1)

Just after Christmas 1838, still a prisoner of the Crown, she was found to be well and truly on the road to motherhood, and was put in the Female Factory at Parramatta, and demoted to “second class” prisoner status. Her infant son, named Henry, was born there on March 17, 1839 (2), with no father listed on the birth or christening records. Her first year in Australia had been a memorable one indeed.

Whether baby Henry was conceived of a consensual relationship or was the result of a Government official or fellow convict exercising what he perceived to be his right, is lost to time. Marcella’s time as an assigned servant at Moreton Bay was marked by such relationships, as she came to the attention of the enlisted men there and, apparently, the Commandant.

On 10 January 1840, Marcella Brown, servant to Mr Dixon, was charged before Commandant Gorman with “Dishonest Conduct in having a bottle of wine in her possession and which she gave to a Soldier of the 80th Regiment on the 5th inst., she being a Prisoner of the Crown at the time, and having no means of honestly obtaining the said bottle of wine.”

It appeared from the evidence that Marcella had the freedom to go about the town, and to the Military Barracks, and indeed into the soldiers’ rooms. On the 5th, she left the room that Private Joseph McLean was working in, returning with a bottle of wine, which she gave to Private James Ratcliffe to take in. Another convict, Mary Bolger, joined the gathering, and became boisterously drunk, resulting in a charge of her own.

The real question, according to Lt Gorman, was where Marcella had obtained the wine. Marcella gave conflicting accounts – taking it from Mr Dixon’s kitchen, or having got it off the last ship to berth at Moreton Bay. She declined to clarify, and even an overnight remand for more evidence to be gathered did not help matters. She was convicted and sentenced to fourteen days’ solitary confinement on bread and water.

Four months later, Marcella was sent to Sydney by Mr Dixon. She was about six months pregnant and probably starting to show. A son, Joseph, was born on 22 July 1840, (3) and christened without a father’s name, at St John’s Parramatta. Who the father might have been is intriguing – the name Joseph was mentioned at her dishonesty trial – she had been in Joseph McLean’s rooms on the night of the drinking session, and may have had a relationship with him during her brief but turbulent Brisbane stay. Or the father may have been someone else entirely.

She had been “carrying on” with Lieutenant Gorman, according to convict John Ford, who taunted Owen Gorman about it in 1841, and threatened to report him to the Governor. Surveyor Dixon, for whom Ford was working, became involved in the contretemps that ensued.

For the men involved, the fallout from the alleged carrying on, and the dispute afterwards, continued for years. Marcella herself was granted a Ticket of Leave in April 1842, on the condition that she remain in the District of Queanbeyan in Central New South Wales. More than twice shy, she stayed out of trouble, living quietly and eventually passing away at the age of 65 in Sydney.

The Surveyor

Surveyor Robert Dixon arrived at Moreton Bay in 1839, whilst in the middle of a dispute with the Surveyor General, over promotion and payment (4). A highly capable surveyor, Dixon, not unlike his colleague Granville Stapylton, had a quarrelsome nature, and did not suffer officialdom gladly.

Dixon’s letters about his dispute with his department head flew back and forth to the Office of the Colonial Secretary, to the point where the Surveyor-General had to explain to Governor Sir George Gipps that he had not preferred charges against Dixon, it was merely a dispute over payment and promotion.

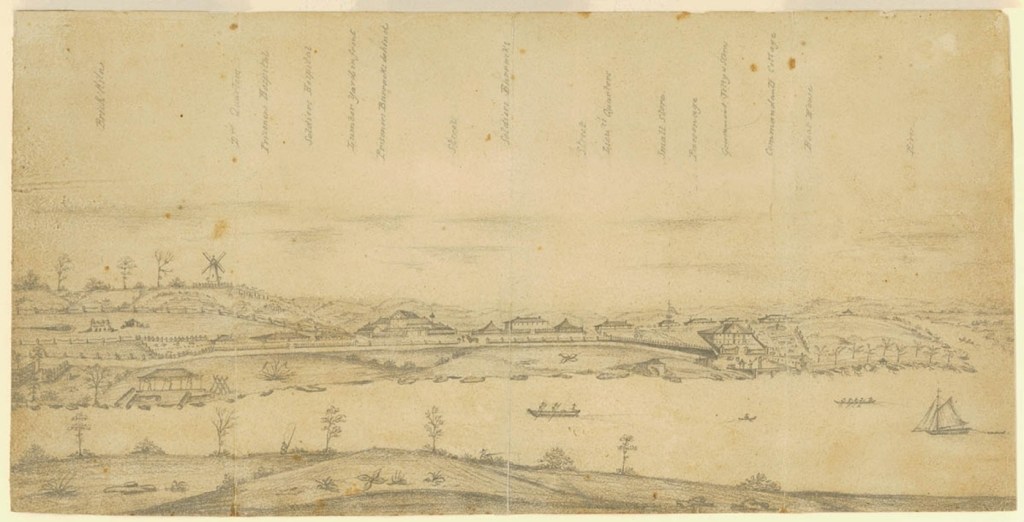

Relieved, Dixon turned his attention to the state of things at Moreton Bay. He did not like what he saw. The quality of articles supplied to him “shameful,” the forage and supplies “inadequate”, and the convicts assigned to the survey “untrained,” thus impeding the survey. There wasn’t enough tea, sugar or tobacco in the Commissariat, and one of his men, a certain George Clark, had “bad habits.” He needed awnings for his tent, another surveyor had lost a boat with provisions, he sought to hire private horses, and was upset by the “slop clothing, boots and duck clothing” supplied. (5)

Dixon married the suitably upper middle-class Margaret Silby at Moreton Bay in July 1839 (the happy event inspiring much official correspondence involving permissions, provisions and lodging), and employed a number of convicts as part of his surveying team, and domestically. One of his family’s servants was Marcella Brown. Another was John Ford.

Just as Dixon was settling in, Owen Gorman relieved Sydney Cotton as Commandant. For a brief time, the men seemed to cooperate, but it was not long before they decided that Moreton Bay wasn’t big for the both of them.

Gorman saw Dixon as a disruptive figure, Dixon saw Gorman as an obstructive figure. As the months went by, Dixon would have had the opportunity to observe, or at least hear gossip about, the activities of the military and male convicts around the convict and indigenous women at Moreton Bay (6). As relations with Gorman gradually broke down, letters again flew back and forth to the beleaguered Colonial Secretary throughout 1840 and early 1841.

Dixon travelled to Sydney without permission in February 1841, returning in time to be involved in the contretemps between John Ford and the Commandant. Gorman alleged that Dixon had obstructed his sentry. By May, Dixon had been removed from the Government payroll, having also annoyed the Surveyor-General by publishing his own map of Moreton Bay, compiled with Survey Department resources.

That seems to have been the last straw for Dixon, who declared war, at least in the epistolary sense. The Commandant was demanding that he be prevented from returning due to his “slanderous and insubordinate conduct.” Dixon decided to write to the Governor, telling His Excellency exactly what was going on at the Bay.

A lengthy investigation of his charges against Gorman struck difficulty with the issue of proof, and although it became clear to the Governor that some misconduct had occurred, it wasn’t enough to sack Gorman or get Dixon reinstated to the Survey Department.

When the convict settlement of Moreton Bay was closed, Dixon applied to lease some Government buildings, but his application was refused. Too many bridges had been burned. He went into various businesses, without any notable success, and died in Sydney in April 1858.

The Commandant

Owen Gorman was Commandant of Moreton Bay from July 1839 to May 1842. Born 1799 in King’s County Ireland, he enlisted as a private at the age of eighteen, and slowly rose through the ranks to Lieutenant of the 80th Leicestershire Regiment in 1833 – the only Commandant of Moreton Bay to do so entirely on merit. He did not see active combat.

He married Margaret Flannagan in Spanish Town, Jamaica in 1818, and they had four sons. His family was with him during his tenure at Moreton Bay.

Gorman was always going to be the last Commandant. When he took over from Cotton in 1839, the Convict Settlement was being prepared to transition to free settlement, and Gorman hoped to use a successful handover as leverage to a lucrative Government position (7). The last thing he needed was a scandal.

Gorman handled a number of the aspects of his position with integrity and aplomb. He worked with the former convict runaway, John Sterry Baker, to chart a new pathway over the ranges to the Darling Downs. He showed genuine leadership when the news of the murders of Assistant Surveyor Granville Stapylton and William Tuck reached Brisbane, personally leading a search party to find the site of the murders, and in so doing, discovering a badly injured survivor of the attack. He conducted the inquest into the circumstances of the murders, which provided history with the most thorough account of the murders to survive.

But the dispute with Robert Dixon brought his other activities to light, and highlighted the almost institutional ill-treatment of women convicts and indigenous women and girls that had been allowed to happen in a remote penal settlement with only the official correspondence with Sydney providing any oversight of its activities.

At first, the accusations made by Robert Dixon were treated by the Governor’s Office as the ramblings of a discontented former employee. Gradually though, the information given by witnesses showed that while no provable charges could be laid against him, there was enough to the stories to make it clear that Gorman’s behaviour had been “unguarded.”

Gorman saw out his commission as Commandant, but was stripped of his Magisterial powers in 1842. Dr Stephen Simpson was sent to the Bay to take over that part of Gorman’s duties, discovering irregularities in the record of the trial of John Ford in the process.

Owen Gorman resigned his commission in the Army in 1845, and moved to Armidale. His marriage ended, and Mrs Gorman was succeeded in his affections by Mary Miliken, some thirty years his junior. Gorman ran a newspaper and with Mary founded a second family that became popular and much-admired in Armidale. He passed away in October 1862. Ironically, his son John became a noted surveyor.

The Colonial Secretary

The Correspondence from the Colonial Secretary’s Office shows the developing tensions between the Commandant and the Surveyor, and the gradual realization that some of the charges made by Dixon against Gorman were not unfounded.

1840

In a bundle of letters to Moreton Bay dated December 28 1840:

“… enclosing a letter from Asst Surveyor Dixon relative to his having applied for Rations on account of one of the men attached to his party … I am instructed by His Excellency the Governor to inform you that you acted very properly in respect to those Rations – and at the same time to request that you will express to Mr Dixon, His Excellency’s decided disapproval of the tone of two of his letters to you of the 30th of October.”

“Having submitted to the Governor your letter of the 14th ultimo, from which it appears that Mr Dixon the surveyor at Moreton Bay does not acknowledge the authority with which you are vested as Commandant. I am directed by His Excellency to request that on receipt of this letter, you will call for the attendance of Mr Dixon, and also of the other Principal Officers of the Settlement, and in their presence express to Mr Dixon the very great surprise with which His Excellency has received the accounts which you have transmitted of his conduct.”

That would have been a very interesting meeting indeed.

1841

In February, Dixon travelled to Sydney. Upon Gorman’s query about this, the Colonial Secretary advised that the Surveyor-General had not given Dixon permission to quit his post at Moreton Bay, and that the Surveyor-General was “by no means pleased at his doing so.”

By April, Dixon was back in Brisbane Town, and on the evening of the 12th was involved in the contretemps between John Ford and the Commandant. Dixon travelled back to Sydney in July, and in August Gorman made an official request that he not be permitted to return.

The storm broke in November 1841. The Colonial Secretary directed that a copy of a letter from Robert Dixon, making “certain charges” (8) be forwarded to the Commandant.

“In transmitting these papers to you the Governor directs me to say that he feels it necessary to call on you for some reply to the charges herein contained, for His Excellency has not failed to perceive that they are founded mostly on hearsay, since they relate to matters in which direct evidence is seldom to be obtained.” (9)

In December, His Excellency was still reassuring Gorman, “If your personal demeanour, and usual conduct have been such as to befit your Station, you can, His Excellency apprehends, have little difficulty in rendering harmless the attacks which are contained in the statements appended to Dixon’s letter.” (10)

1842

But a month later, things were bleak. While Gorman was not to be charged, His Excellency’s hitherto unwavering faith had been shaken. Officially.

“His Excellency considers you have exculpated yourself from the most serious charges and that no further investigation of them seems to him to be necessary. Although, however, His Excellency considers you to stand acquitted of these charges, he regrets to say, he cannot think you have altogether acquitted yourself in a manner to command the respect of the various persons residing at Moreton Bay; and although he feels bound to acquit you of any criminal intercourse with Convict or Aboriginal women, he cannot think that your conduct must at times in respect of them to have been very unguarded.” (11)

As Gorman digested this rebuke, Dixon continued to worry at his problems. In February, he wrote to the Colonial Secretary, explaining why he had kept certain items from the Survey Department, asking for a Court hearing to explore the injustices done to him by the Department, Lieutenant Gorman at Moreton Bay, and the vexed matter of the unsanctioned survey map. However, he would, for compensation, be willing to return the Government items and the “insulting letters” about Gorman.

His Excellency wasn’t impressed by that approach, and explored with the Crown Solicitor the possibility of laying charges. Happily for all concerned, Major Mitchell, the Surveyor-General, obtained permission to purchase Dixon’s map, and by May, was happy to report the return of the surveying equipment. Dixon did not obtain reinstatement, however.

The end of the Moreton Bay Convict Settlement was marked with a final communique from the Colonial Secretary, who advised that the detachment of the 80th Regiment would be recalled. And, with faith in Gorman’s stewardship of the handover decidedly shaky,

“His Excellency has desired me to request that previous to leaving Moreton Bay, you will deliver over to Dr Simpson the Crown Commissioner of the District, all the papers, books, documents of any description in your charge, relating either to the Civil business of this Government, or to Convict Services, and also, all Buildings, Stores &c., which may be in your charge or care.” (12)

The Incident at Brisbane Town

John Ford (born 1800) had been sentenced at Gloucester Quarter Sessions to seven years’ transportation to Australia while still a teenager. After an eight-month voyage on the Atlas, arrived in Sydney on 05 February 1820. Ford completed his sentence in January 1826, and had a Certificate of Freedom issued. It didn’t last. In September 1826, he was convicted of Robbery at the Criminal Court in Sydney and sentenced to death. This was commuted to life at Moreton Bay in double irons, and in 1836, mitigated to 7 years. He was an old Moreton Bay hand of fourteen years when he was assigned to work for Surveyor Dixon.

Ford had survived Logan, Clunie, Fyans and Cotton as Commandants at Moreton Bay. Gorman clearly was another matter. Ford was loyal to Robert Dixon, and was rewarded with approval to work on the Survey rather than return to Sydney.

However on 12th April 1841, with Dixon on the outs and Ford’s colonial sentence expired, a trip to Sydney Town loomed on the horizon. Ford decided to go out with a bang.

As the Commandant boarded the Cutter John from a ferry, Ford called out, “Gorman, I will report you as soon as I get to Sydney to the Governor.” In case Gorman was in any doubt that he was being taunted in front of his men and the various convicts present, Ford called out again. “Lieutenant Gorman! Gorman, I will report you as soon as I reach Sydney for the carryings on that you had at Mr Dixon’s house with that infernal vagabond woman.”

This was too much for the Commandant. He called out for a Constable, but there wasn’t one handy. Gorman had the ferry recalled to the Cutter, so that he could deal with this personally. His sentry at the wharf, Robert Whitmore, was tasked with scaring up a Constable. The first person Whitmore saw was William Crabb, another convict in the employ of Robert Dixon. He asked Crabb to go for a Constable, but Crabb refused.

At that moment, Robert Dixon and “about eight of his men rushed down the (ferry) steps with great force.” Dixon ordered his men to get his boat, something that Whitmore considered to be “quite contrary” to his orders. Whitmore stood his ground, and called out to Gorman to confirm whether Mr Dixon must send for his boat. The answer was a decided “no.”

According to Whitmore, Dixon asserted that the soldier (and by extension the Commandant) “had no command over him or his boat, that he should have his boat where he thought it proper and he still insisted that his man servant go for his boat, and that I might fire away as far as he liked.”

Whitmore made threats to run people through with a bayonet if they didn’t clear the wharf. Dixon asserted that the Commandant was a “cowardly scoundrel.” Things became, if not civilised, at least markedly calmer when the Commandant’s ferry, with another sentry and Ford in tow, drew in to the wharf.

Ford was taken to the Prisoners Barracks and given into custody. As the sentries, Whitmore and Turnbull, were taking the road back to the Soldiers Barracks, they met the Surveyor and two of his colleagues. Dixon wanted to know if Ford had seemed drunk, and was told that it wasn’t possible to tell from his appearance. He then asked the men if they knew what Ford said. They made no reply, and Dixon turned to leave, saying “It’s no use asking any of you soldiers.”

The following morning, Lieutenant Gorman tried Ford for “making threats and insolent language” to him, thus being the complainant and the adjudicator in the same matter. From evidence given at a later inquiry, it seems that the Commandant wrote the record of the hearing, rather than use his clerk, and did not read depositions to the hearing, or have the witnesses sign their evidence.

The two sentries gave their evidence of the events at the wharf, then Ford was given the opportunity to give his evidence. Ford stated that he had nothing to say, beyond what he would tell the Governor, and what he told Mr Dixon. He bravely called two witnesses in his defence.

The first witness was brief. It was Private Joseph McLean, 80th Regiment. “Did you ever see Lieutenant Gorman and Marcella Brown, who was servant to Mr Dixon in any private or concealed or criminal way together?” “No, I never did.”

The next witness was Mary Bolger, another female convict, who knew Marcella Brown, and had taken part in the January 1840 drinking session with her and the previous witness, Joseph McLean. She would go on to be Gorman’s servant.

Ford asked the same question to Mary Bolger, who replied, “Upon my oath, I never seen Lieutenant Gorman in any private or concealed or criminal way with Marcella Brown, nor I never heard a word of this kind from Marcella Brown.” Bolger added that she had seen Marcella on her last day at Moreton Bay, and that Brown had said in part, “Now, Mary, I am going. I may blame McLean and old Ford for the whole of it.” (The next sentence in the record is very faint and runs into the margin, unfortunately.)

Lieutenant Gorman found Ford guilty, and sentenced him to 100 lashes. (13)

Ford left Moreton Bay in chains in 1841. Dixon left Moreton Bay in 1841, unemployed and fighting for reinstatement. Gorman left Moreton Bay in 1842 with his Regiment, but a stain on his character. Mary Bolger left Moreton Bay in 1841, having lasted a only short time in the service of the Gorman family, who locked her in her room at night to stop her sneaking off to drink and misbehave. Mary found ways to get out. On Mary’s return to Sydney, she married a fellow-convict and together they ran a very interesting household, if a contemporary news report is to be believed. (14)

Marcella Brown had left Moreton Bay first, returning to the Female Factory to have the child conceived in Brisbane. Was she an infernal vagabond of a woman? It’s hard to know. Perhaps she was more attractive than some of her contemporaries, and received more attention as a result. Her description on the Convict Indents – red hair, fair, grey eyes – sounds quite comely. Poor Mary Bolger fared less well in the Indents. A few years older, she was described as freckled and ruddy-faced, with sandy hair, a front tooth missing, and with scars on her face and one arm.

Marcella was a young convict woman, and her life is recorded only in the documents retained by the Government. She had no biography, no discoveries to her name, not even a colourful newspaper article . She committed a crime back in Ireland, and forfeited her homeland and family. In a new country, aged only 22, she fell foul not of the law, but of men. She was probably no more an infernal vagabond than the men she encountered.

(1.) I suspect Marcella Brown is the Marcella Croghan who married Richard Brown at Meath on 15 February 1836.

(2.) Reg 645/1839 V 1839645 23A

(3.) Reference #993953

(4.) In London in 1838, Dixon published an unauthorised map of the Colony, and was denied reinstatement for a time.

(5.) After a bizarre Google search for “duck clothing,” I am indebted to Britannica for advising that duck clothing was made of “a plain, durable, woven material, lighter than canvas.” The earlier search led me to believe that the Commissariat might have kindly provided such garments in order that ducks should be spared the indignity of waddling about the settlement in a state of nudity.

(6.) The treatment of convict women and indigenous women during the convict era at Moreton Bay is distressing. The Book of Trials contains accounts of teenage indigenous girls being abducted by and considered the property of convicts (who gave several of the girls gonorrhea in the process), and skirmishes with the local indigenous groups over the treatment of their women.

(7.) 28 December 1840.

(8.) The allegations had to do with, among other things, one of Gorman’s visits to the Bay islands with his son, and their actions towards indigenous women whilst there.

(9.) 28 November 1841.

(10.) 04 December 1841.

(11.) 19 January 1842.

(12.) 03 May 1842.

(13.) The penalty was discounted to 75, and Ford was sent to Sydney, where he was imprisoned, then assigned to a road gang. He was granted clemency on the petition of Andrew Petrie, Rev Handt of the German Station, Robert Dixon, and Dr Stephen Simpson.

(14.) Mary Bulger, the wife of a man named Wilson, was introduced to the notice of the Bench, for conduct decidedly the reverse to that which Lord Chesterfield lays down as the concomitant of well bred Society. It appeared that Mr. Wilson was a resident of that locality near the Windsor Toll Bar, in this town, which has acquired the name of St. Giles from the character and habits of the majority of its inhabitants.

Over the various denizens therein resident — he had acquired, from the fact of his being a “thorough good man,” in his having suffered more crosses for declensions from the square than any half-dozen men in the Colony – the regal appellation of “The King”—and his domicile, from its having two whole chairs and an unbroken stool, was styled “The Palace.”

At this abode, nightly Levees were held, the privilege of Entree to which, was granted to such only who had (or ought to have) been at Norfolk Island, passed the ordeal of in Iron Gang, or were Runaways, and was purchasable on treating the company to glasses all round, an event which had, in all probability, occurred on Sunday evening, as the prisoner in an elated buoyancy of spirit, meeting with one of the constables, attacked by tongue with expressions which decency forbids the publication of, and then made her heels save the capture of her body, by running to “The Palace,” on arrival at which, the affronted Constable found her protected by such a numerous body of blackguards, ready to do any thing for their Queen, that it was dangerous to interfere, and therefore had to wait until the next day to apprehend her.

Such was the constable’s version of the affair — to which her husband King Wilson, brought forward two of his subjects to prove quite the reverse, two individuals, who swore to hearing his wife’s conversation, which was only language of the most playful character — at a no less distance than one hundred yards but as the loose garments—quivering voices— unwashed faces — blood-shot eyes, and rats-tailed hair of the witnesses did not give a prepossessing appearance to their testimony, the Court was rather wavering, when his Majesty begged an honest Constable named Murphy might be examined, which request was at once granted and settled the case.

It is seldom that the Police are accused of being “too modest,” but this functionary was of that character that he had to be requested several times by the Court to repeat what he heard, before he could twist his mouth into the proper, lisping form to give these expressions forth, and when blushing like a maiden they were uttered, they were found to be of a far more filthy character than the evidence had deposed to. On which Mary was sent ten days to the cells to impress the necessity of a future Molli-fication of language. Parramatta Chronicle and Cumberland General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 – 1845), Saturday 1 March 1845, page 2

Trial of Marcella Brown, 1840

Marcella Brown

Servant to Mr Dixon

Ship Diamond

Brisbane Town, 10th January 1840, charged with Dishonest Conduct in having a Bottle of Wine in her possession and which she gave to a Soldier of the 80th Regiment, on the 5th inst., she being a Prisoner of the Crown at the time, and having no means of honestly obtaining the said Bottle of Wine.

1st Evidence – Private James Ratcliffe, 80th Regiment, being duly sworn deposeth that on Sunday Evening last the 5th inst., e received a Bottle of Wine from the Prisoner, who requested him to bring it up to the Room which Private Joseph McLean, 80th Regiment, worked in.

2nd Evidence – Private Robert Whitmore of the 80th Regiment, being duly sworn deposeth that on Sunday Evening last the 5th inst., he was in the room in which Private McLean, 80th Regt., worked in the Barracks.

The Prisoner Marcella Brown now before the Court was there,; she went out and returned in a short time accompanied by Private Ratcliffe with a bottle of Wine, which she gave to them to drink, and which was drank accordingly.

Prisoner Marcella Brown is remanded until tomorrow morning for the purpose of obtaining further evidence as to the theft. Brisbane Town, 11th January 1840.

The Prisoner Marcella Brown being again before the Court, and no other Evidence appearing against hr, is called on to state anything she may have to urge in her defence.

She first states she got the Wine in her Master’s Kitchen, and secondly that she brought it there herself since she had a (indistinct) sine the last Ship was in when she obtained it with five Bottles of Wine more, and two Bottles of Run from the said Ship, but she declines calling on any Evidence to prove her statement.

Opinion – Guilty of Dishonest Conduct as set forth in the charge, and sentenced to be placed in Solitary confinement for a period of fourteen days in the Cells at Brisbane Town on bread and water. O Gorman.

Trials of Mary Bolger

Mary Bolger Brisbane Town, 11 January 1840

Prisoner of the Crown Charged with being drunk on Sunday 5th inst.

Ship: Whitby

Constable Francis Black being duly sworn deposeth that he saw Mary Bolger on Sunday evening last, drunk and tearing her clothes.

Defence – the Prisoner being called on to state anything she may have to urge in her defence, acknowledges the Crime, and states that she got a glass of Rum from Whitmore and had part of a bottle of Wine that Marcella Brown brought to the Room where they were, but that she cannot tell where Marcella Brown got the Wine. She believes it to have been brought from Mr Dixon’s house.

Guilty of the charge brought against her and sentenced to fourteen days Solitary Confinement on bread and water in the Cells of Brisbane Town. O. Gorman.

Mary Bolger Brisbane Town, 29 July 1841

Prisoner of the Crown Charged by Mr Wm Whyte with Drunkenness and Improper Conduct

Ship: Whitby

Wm Whyte being duly sworn states that o the evening of the 27th instant, it was reported to him that this prisoner was drunk and conducting herself in a highly disreputable manner with Francis Black per Sussex in a room where she was said to be in and in which he found the prisoner very drunk, and the aforesaid Francis Black with her. (Defendant; nothing to say.)

The Prisoner having been found Guilty of the Charge preferred against her is sentenced to ten days solitary confinement in the Cells on bread and water. O Gorman.

Prisoner of the Crown Mary Bolger, Ship Whitby, now an assigned servant to Mrs Gorman at Moreton Bay. Charged with disobedience of orders and improper conduct at Brisbane Town on the night of 29th August 1841.

1st Evidence – Lieutenant Owen Gorman, 80th Regiment, duly sworn deposeth: The Prisoner now before the Court is an assigned servant of Mrs Gorman, who was usually locked up at night in her room to prevent her from going abroad and who on the night of the 29th August last, found means to escape through the connivance of other servants. About 10 o’clock I found the door of her room was locked but the prisoner had escaped. I sent immediately for the Constables and they went in pursuit of her but before they returned, I found her sitting under a tree and as soon as she saw me she came up to me. This was nearly 11 at night. I immediately sent her off to confinement. Prisoner found guilty of disobedience of orders an sentenced to two months’ imprisonment. Francis W. Forbes, JP.

Sources:

- Australian Death Index, 1787-1985

- Book of Trials Held at Moreton Bay, 1835-1842. Item ID 869682, Part 1. Queensland State Archives.

- Chronological register of prisoners at Moreton Bay, Queensland State Archives, Item Representation ID 3649135

- Cranfield, Louis R, ‘Dixon, Robert (1800-1858): Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, (MUP), 1966.

- Cranfield, Louis R, ‘Early Commandants of Moreton Bay’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Volume 7, Issue 2. Pp 385-398. Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 1964

- Fisher, Rod (ed) – ‘Brisbane: The Aboriginal presence 1824-1860’, Brisbane History Group, Papers No. 11, 1992. Kelvin Grove, Queensland.

- Fraser, Douglas Were, ‘Early Public Service in Queensland’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Volume 7, Issue 1: pp 48-71. Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 1963.

- Harrison, Dr Jennifer – ‘The Moreton Bay commandants and their families, 1824-1842. [Article presented to a History of Women in Queensland Seminar at the Commissariat Store on 13 August 2005],’ Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 2007-11, Volume 20 (4), pp 148-158.

- New South Wales, Australia, Certificates of Freedom, 1810-1814, 1827-1867.

- New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary – Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822-1860, State Library of Queensland.

- New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1856. Moreton Bay: Letters from Colonial Secretary to Commandant, 1832-1853.

- New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842.

- New South Wales, Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930.

- New South Wales, Australia, St John’s Parramatta, Baptisms, 1790-1916

- New South Wales, Australia, Tickets of Leave, 1810-1869.

2 Comments