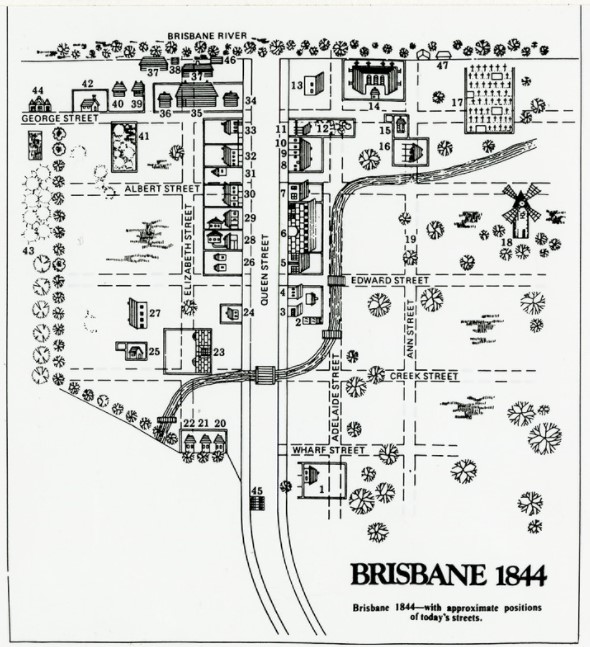

The Sketch Map of Brisbane Town in 1844, and the stories behind it.

16. Wright’s Hotel

At first, hotels were few in old Brisbane Town. The hospitable Scot, Alexander Wright, was the proprietor of one of the larger and more respectable ones, The Caledonian Hotel, between Queen and Ann Streets. Mr Wright boasted of the select nature of his establishment, but Thomas Roper recalled it as being out in the fields. Possibly surrounded by bullocks when Mr Mandell was not up-country.

“All around from this on every side was open Commanage. The camping ground of bullock teams, said teams would frequently monopolise Queen Street during the process of receiving loading for Up Country. Many of the bullocks would be lying down in their yokes chewing the cud of contentment perfectly indifferent to the requirements of traffic regulations.”

Thomas Roper, A Walk Through Old Brisbane

Many years later, the Caledonian Hotel became Caledonian House, home to a Seminary for Young Ladies, run by a formidable-sounding woman named Mrs Bulgin, who I’m sure made it remained both quiet and respectable.

17. General Cemetery

Gerler’s map shows a cemetery roughly in the area of North Quay and Herschel Streets. He places the site as close to the Brisbane Hospital, and near something called “The First Tombstone (two graves)” on the riverbank. In the modern interpretation of the map (end of post), that cemetery crosses modern-day George Street.

Official survey maps and plans locate the Burial Ground in the Saul and Skew Street location – Henry Wade in 1844 (the same year as Gerler’s sketched map) shows it highlighted in yellow at the centre left of the picture below. The same is true of Robert Dixon’s 1840 survey, in which they are so far away from the buildings of Brisbane that the words “Burial Ground” are cut off in the digital representation.

It would be understandable if Gerler had misplaced the burial ground slightly in his sketched map, putting it closer to the Hospital than it actually was.

However, some early Queenslanders had strong memories of a cemetery closer to town. Some spoke of soldiers’ graves by the riverbank at North Quay, others of a cemetery closer to Roma Street, other still of one at Herschel Street and North Quay (roughly where Gerler draws it).

It is possible that there was a very early burial place for convicts and soldiers, much closer to the settlement, before the Saul/Skew Street site was selected for the purpose. However, the soldiers’ graves described appear to have been confused with the graves of three children, which were placed on the riverbank at North Quay in the 1830s.

The children were:

William Henry Roberts, son of Charles Roberts Commissariat Department. Died November 15, 1831, aged 5 years and 2 months.

Peter Macauley, son of Pte Peter Macauley, 17th Regt. Drowned January 05, 1832, aged 5 years, 8 months.

Jane Pittard, daughter of John Pittard, Sgt, 57th Regt. Died January 29, 1833 aged 12 months, 13 days.

A painting of the river bend from North Quay that shows the three sad little graves overlooking the river. Over the years, progress threatened to obliterate them. In August 1881 a special license was obtained to exhume the children and reinter them at Toowong Cemetery. It’s rather touching that such care was taken, and is still taken today, with the graves of three youngsters who died nearly 200 years ago.

By 1844, burials had commenced at the Hale Street Cemetery, much further from town (at the time), and the Skew Street Cemetery fell into disrepair, a state lamented in the Moreton Bay Courier in 1846. “There is not even a fence to restrain pigs and other animals from rooting and roving over the dwellings of the dead.”

18. Tread and Windmill

The Windmill at Wickham Terrace was built with convict labour, for convict labour, between 1828 and 1829. On 10 September 1829, Michael Collins, a Lancastrian at the beginning of a 7-year Colonial sentence for stealing in a dwelling house, became entangled in the treadmill, and died of terrible injuries.

There were sails attached to the Windmill, but these did not function properly, due either to the placement of the building or a faulty mechanism (historians disagree on this point). In order to crush the grain, convicts had to be employed to move the treadmill by foot, taking care not to fall out of step after the horrible example of Collins. The men dreamed of windy weather, which would make the sails come to life, at least for a while.

In the years since the penal colony, the Windmill has been used as an observatory, signal station, gallows (once), television and radio broadcasting hub, and, fictionally, as the lurking place for the Morton Bay Courier’s Windmill Correspondent. The building survived its closest shave in the early 1850s, when a financially embarrassed Government thought of putting it up for private sale, or demolishing it for the bricks. Happily, that did not occur, although the prospect of this occurring led locals to scavenge the building for whatever useful metal or stone they could carry away.

19. Edmonstone’s Paddock

Edmonstone’s paddock was located, according to the modern version of Gerler’s map, right in the middle of Ann Street, but was more likely a little further west, nearer to Windmill Hill. George Edmonstone was Brisbane Town’s butcher, and his paddock was where his livestock resided prior to adorning the local tables.

20. Old R. Jones

Old R. Jones indeed. The man was Richard Jones, Esq., 1786-1852, to the likes of you Herr Gerler. At the time Gerler was sketching out his map, Richard Jones was residing at Petrie Bight, in what I imagine was a row of quite attractive cottages, given the status of the occupants; next door to Dr Simpson and “Old Major Prior”. Richard Jones lived in the house closest to Queen Street, across from Andrew Petrie.

Jones was educated in London, making a success of commerce, while dreaming of vast landholdings and flocks. He first lived and worked in New South Wales from 1809, starting the company Jones & Riley, which at the time had no competition in the Colony, something that peeved Lachlan Macquarie no end. Clearly, Jones was doing something right.

After a spell in China and then back in England, Jones decided that life as a pastoralist in New South Wales was just the thing – and brought the first Saxony sheep (Saxon Merino sheep) to Australia. He expanded his interests, and was soon one of the largest landholders in the Colony. He still took part in commercial activities with his old firm.

By the end of the 1820s Jones was among other things, a bank president, pastoralist, company director, whaling boat owner and political activist. His fortunes took a blow in the depression of the early 1840s, and he was forced to sell all of his estates, ships and assets. It was at this time that Richard Jones moved to Moreton Bay, and gradually recovered his standing, becoming a substantial landowner in the district, then entered politics, becoming the first Member for Stanley Boroughs.

It’s quite an exhausting curriculum vitae, and I suppose R. Jones was considered “old” (66) when he passed away at his home in New Farm, Brisbane in 1852.

21. Dr. Simpson (the first Commissioner)

Dr Stephen Simpson was another Victorian Englishman who had a life filled with adventure, high public office and general public esteem. After a military career, he studied medicine, and became interested in homeopathy, to the derision of his peers, who preferred bleeding and leeches.

In 1840, he travelled to Australia, and by 1841 found himself appointed to the Bench at Brisbane Town when Commandant Owen Gorman was stripped of the magistracy. Simpson eventually took over as Acting Superintendent of the town until Captain John Wickham arrived.

Dr Simpson’s various roles in Moreton Bay included Police Magistrate, Commissioner for Crown Lands, Acting Colonial Surgeon, Justice of the Peace, trustee of Brisbane Hospital, returning officer, and later, Member of the Legislative Council for the newly-separated Colony of Queensland.

Dr Simpson bought land in the Goodna and Redbank areas, establishing himself at Woogaroo, where he employed David Bracewell (Wandi) and James Davis (Duramboi).

Despite the slightly terrifying portrait (above) held by the State Library of Queensland, Simpson was a respected and well-liked man, by indigenous and European Australians alike. According to legend, when Henry Mort (not, I think, the Brisbane milkman) asked an Aboriginal gent, ‘Who is God?’ he received the reply ‘Carbon white fellow, like it Doctor Simpson, sit down here’.

22. Old Major Prior

“Old Major Prior” or Major Thomas Prior, lived and worked in Brisbane for a number of years, and was known as a quietly dignified man. He was an Irishman, from Rathdowney in King’s County, and fought at Waterloo as a lieutenant in18th Regiment of Light Dragoons (Hussars). The gentleman at the right is an 18th Regiment Light Dragoon from 1809. A whole regiment of them thus attired would surely have alarmed any approaching Frenchman.

In 1854, Major Prior was elevated to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and he remained in Brisbane until the late 1850s, when he returned to the United Kingdom, before passing away in July 1864.

23. The Gaol

The Brisbane Gaol in identified by Gerler in 1844 was the old convict era building called the Female Factory, which had fallen into disrepair after the female convicts were relocated to Eagle Farm, where they could get into less mischief (or in fact, where the soldiers and male convicts would make less mischief at their expense).

Scarcely fit for purpose when it was built, it was a largely roofless semi-ruin in 1844. Any persons sentenced to custodial terms or awaiting trial on serious offences were sent to Sydney, and local ruffians were housed for very brief periods in the town lock-up (9 on the map).

After much delay and more pleading with Sydney for funds, the Gaol at Queen Street was repaired and opened in 1850. Within a decade, the population and its criminal leanings had increased to the point where a more commodious prison had to be built at Petrie Terrace. Which then had to be augmented by St Helena Island, and then replaced by yet another, larger, Gaol at Boggo Road.

24. Skyring’s Beehives (soft goods shop)

Daniel Skyring was granted permission to travel to, and set up in, Moreton Bay in 1843, at the dawn of free settlement. He was the son of a builder, and arrived in Sydney in 1833 with his wife and children. He worked throughout the Colony until he decided to open a business in Brisbane as a trader, general storekeeper and for a while, dairyman.

The Beehive, also called the Ready Money Beehive Store, operated on a cash basis at a time when IOUs were pretty much the currency of the Colony, a system open for exploitation. By trading for cash, Skyring established an honest and respectable business in the town.

Despite being highly successful in quite a small town, Daniel Skyring kept a low public profile, involved himself in no local dramas, and lived on to a grand old age, dying in 1882.

25. Hayes, milkman

Thomas Hayes was one of Brisbane’s milkmen, along with the mysterious Mr Mort. He was evidently successful enough to purchase land from another Colonist, which Tom Dowse was instructed to sell in 1849. Mr Hayes had other ideas:

THE public are hereby cautioned from purchasing my piece of Ground, situate in North Brisbane, being part of Lot No. 2 of Section No. 2, containing 33 feet more or less; the which allotment I purchased from Michael Doyle, and hold his receipt for the same.

Thomas Hayes.

A few years later, Mr Hayes was summoned by a John Duggan for assault. The Bench and the Courier decided that the matter was “merely an ordinary quarrel” and a fine equal to an ordinary quarrel was issued.

Thomas Hayes died in 1879 at the age of 69.

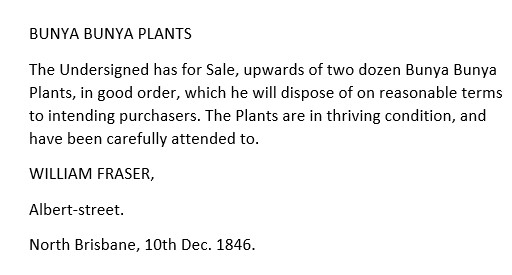

26. Brothers Fraser (first houses)

Who built the first house or houses in Brisbane Town is a subject of some debate. Gerler fixes this honour on Brothers Fraser. Their houses on Queen Street may have been the first built in the time of free settlement, but I expect that Andrew Petrie holds the honour for a private dwelling.

The brothers Fraser were William and Thomas Fraser (sometimes spelled Frazer). William first pops up offering Bunya Bunya plants (in thriving condition) for sale in 1846. In 1848,William Fraser was the man brought to Kangaroo Point by Chief Constable Fitzgerald to assist him in the removal of Robert Cox’s dead body from the riverbank.

In 1851, the brothers Fraser, both freeholders, were on the electoral list for North Brisbane, and at the end of the decade, Thomas was the owner and proprietor of the cutter Adventure.

After a court case involving the theft of Thomas’ watch, the brothers Fraser disappear from the records in the early 1860s.

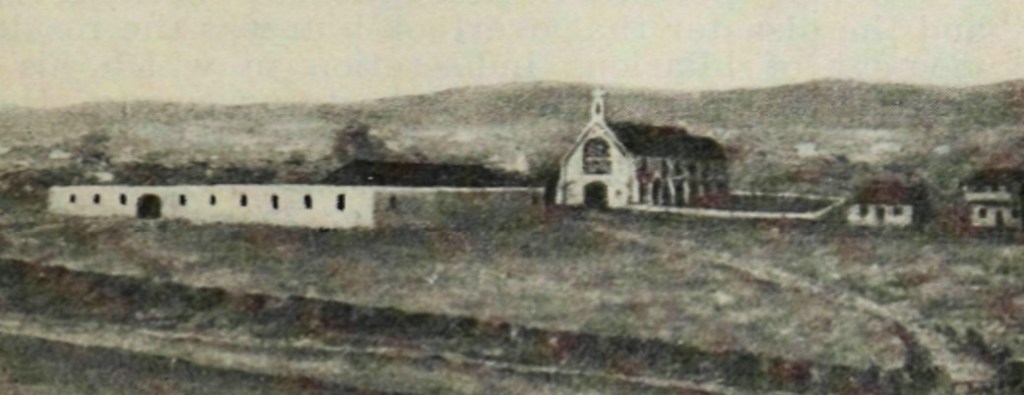

27. Catholic Church

St Stephens’ Church was built by Alexander Goold, and completed in 1849-50. The building is now known as Pugin’s Chapel, after the architect Augustus Welby Pugin, who went on to design such trifling edifices as the Palace of Westminster. Before it was opened, Father Hanly tended to his flock in a converted barn close by – the structure Gerler noted as the church in 1844.

Poor Rev. Gregor, and his successor, Rev. Glennie, struggling to have basic modifications made to a “ruinous building” in the lumber yard, must have looked upon the plans for the beautiful, purpose-built, Gothic church with despair.

Fortunately this building survives today in the grounds of the newer St Stephens’ Cathedral on Elizabeth Street, having somehow escaped the local mania for replacing sandstone with steel and glass.

28. McLean’s Blacksmith’s Shop

Lachlan McLean was Brisbane’s first Scottish blacksmith (the second was James Davis), and in the 1840s he ran a smithy directly opposite the Convict Barracks in Queen Street, moving to Albert Street by 1852. He arrived at Moreton Bay in 1843, with a young family that continued to grow in Brisbane.

McLean was a devout Presbyterian, and quite a conservative one. He was one of several prominent Brisbane Presbyterians in 1849 who objected to the adoption of a “broad Evangelical Alliance” by the Church.

His business was profitable, and he was responsive to the times – canny enough to offer drays and other items for the diggings when the Queensland gold rush began.

WANTED, a Stout Youth as an out-door APPRENTICE to the Blacksmith Trade. Apply to LACHLAN McLEAN, Albert Street.

Advertisement, 1858

I imagine that he wanted a sturdy, healthy youth, rather than a chubby one…

Life had its happy moments – when his eldest daughter Anne married in 1858, and some very sad moments. His 12 year old son James died in 1859.

Perhaps it was grief at the loss of his son James, or the fact that his older sons had gained majority and were experienced enough to take over at the blacksmith shop, that made up his mind, for at the end of 1859, Lachlan announced his retirement.

LACHLAN McLEAN, while grateful for the support he has received during the time he has been in business in Brisbane, begs to inform his numerous friends and the public that he has disposed of his Business to his SONS, W. and A. McLEAN, who will carry on the same in Albert and George Streets.

The following year, McLean ran for a seat on the municipal council, and although he polled respectably, he was not successful.

Lachlan McLean died aged 54 at his Albert Street home on Tuesday 04 March 1862.

29. Edmonstone’s butcher

George Edmonstone was a Scottish-born butcher, who rose from plying his trade in Queen Street to become a member of Parliament. He was another early Colonist who thrived in business, setting up shop at a time when the valuable trade with and through the Darling Downs was being established.

Edmonstone then entered local politics, becoming a member of Brisbane’s first municipal council in 1859. He also served in the Legislative Assembly, representing East Moreton in 1860-67, Brisbane in 1869-73 and Wickham in 1873-77. (He was not alone in mixing the butcher’s trade with a career in public office – another Queen Street butcher, Patrick Mayne, adored a good barney, found city council politics very much to his liking.)

George Edmonstone’s political career was long and distinguished not by rousing speeches, but quiet determination to see worthwhile projects through. Brisbane can thank his persistence for the Breakfast Creek and Victoria bridges, Brisbane Central School, the Toowong Cemetery and the Ann Street Presbyterian Church.

Ill-health in his later years brought on his retirement, and he died in March 1883. The 12 year old Scottish boy who started working to support his family when his father died, had become the Honourable Mr George Edmonstone.

30. Bow’s Hotel

David Bow was the licensee of the Victoria Hotel, which tended to attract the working man rather than the gentleman. His career in early Brisbane is typical of many at the time – he started with high hopes and success, became insolvent, suffered a family tragedy and then left after lengthy administration of his estate. Still, he made an impact on the town, and his name remained familiar to old Colonists, who recalled the early meetings to agitate for separation that took place in the Victoria.

In Brisbane in the 1840s, there was of course no system of street lighting, and publicans were required to keep a lamp burning all night to light the way for those who ventured out in the night. Even with a lamp or two burning, navigating the potholed, unpaved streets at night would have been quite a challenge. On May 12 1847, Mr Bow fell foul of a newly-sworn constable, Bartholomew Hore, who noticed that the lamp was out between two and three that morning. Constable Hore kept an eye on the premises, and took Bow to Court when he saw that the lamp was not re-lit until daybreak. Thankfully there was no actual crime occurring to distract the constable from this vital task. Bow called witnesses to rebut the Constable’s evidence, but the Bench found there was no evidence that the light was on, and decided to fine Mr Bow 20s. and costs.

In July 1847 one Thomas Hawkins, overseer, took Bow to court, claiming that he was refused service. One can only imagine how unruly Mr Hawkins had been on that occasion, given the boisterous nature of early Brisbane. Dr Lang recalled with horror witnessing an occasion when some shearers, drinking their wages, decided to settle a dispute by riding their horses into a pub and trying to use the tables for steeple-chasing. Unsurprisingly, this venture ended poorly for the rider (low ceilings). Mr Bow was able to cast doubt upon the case made by Mr Hawkins, and the bench dismissed the charge.

1848 was a desperate year for David Bow. In February, he entered into insolvency proceedings – his business no doubt affected at least in part by the IOU system of currency then in vogue. In June, his wife died suddenly. Mrs Bow was in her room with her young son one morning and suffered a seizure, falling down and hitting her head on an open box in the room. Her daughter gave evidence that Mrs Bow had suffered headaches in the days prior. By the time the doctor arrived, Mrs Bow (her first name was not mentioned in the reports) was lying on a couch, unable to speak, with the left side of her face swollen. She was having trouble breathing. Because it was 1848, the doctor bled her to see if that would relieve her condition, but she died after the procedure. Her death was, the doctor opined, due to sanguineous apoplexy (a stroke), and “A Sudden Visitation of God” was recorded.

By this unfortunate occurrence, a young family has been left to mourn the loss of an affectionate parent. The deceased was well respected by her neighbours and townsfolk, a large number of whom attended her remains on the following day to her final resting place.

Sydney Morning Herald, 14 June 1848.

In Part 3: a meddlesome priest, some landed gentry, a few tragic endings and the scion of a great financial house.

1 Comment