In 1848, the Brisbane and Ipswich newspapers were fascinated by the presence of The Flying Pieman, William King, who arrived in this part of the colony and proceeded to perform a lot of highly popular feats of pedestrian endurance and speed. We were rather starved of entertainment in those days, so seeing a ribbon-bedecked chap walking around rather quickly made for a good day out.

Here are the challenges he set for himself in his last run of performances in Brisbane.

– To run, wheeling a barrow, half a mile,

– To run backwards half a mile,

– To run forwards, half a mile,

-To pick up, separately, fifty stones, placed one yard apart, and place them in a basket or box,

– To walk a mile,

– To draw any lady, weighing from 10 to 14 stone, for one mile, in a gig or spring chaise-cart,

– And to take fifty flying leaps, 2 feet 6 inches in height, having ten yards to run between each leap.

It’s improbable that any lady weighing 10 to 14 stone would be willing to admit the fact in public, let alone make herself the object of amusement for the unwashed by being dragged around the town in a cart by a pastry vendor. Any well-upholstered lady worth her corsetry would prefer to tell the pieman to take a flying leap. In fact, take fifty.

William King returned to Sydney and became less active, and more eccentric as the years passed, and eventually died a pauper in the Liverpool Asylum in 1873.

The term “Flying Pieman” seems to have come from London in the 1700s. These piemen went about town on foot with their hot, fresh pies and rolls on trays and in baskets, hurrying to sell their wares in the streets before they could grow cold or stale. They were known for their energy and their ringing calls to the masses to partake of their goods.

There were some less reputable Flying Piemen who offered oddly-flavoured beef pies in neighbourhoods where cats and dogs went missing on a regular basis, particularly in the neighbourhood of Bartholomew Fair.

In Australia, the identity of the Flying Pieman seems to have passed from one public eccentric to another in succession, rather like the title of Dread Pirate Roberts. The Flying Pieman who directly preceded King was certainly one of the oddest public figures this nation has known.

Nathaniel McCulloch, alias the Flying Pieman

Nathaniel McCulloch (sometimes spelled McCullock), c.1801 -1839, was the first person In Australia to gain notoriety under the nickname Flying Pieman. Archival research based on the few clues about his early life suggests that he was an Irishman who was transported to Van Diemen’s Land for seven years in 1820. There were some incidents in the ensuing years in Hobart Town, and after a few lashings here and there, he obtained his freedom and travelled to Sydney to work for a respected crockery merchant in Sydney, around 1827.

McCulloch became proprietor of the Spode Warehouse by the end of the 1820s. He was well-known about town as a successful young businessman and husband, albeit an emancipist. If only he hadn’t such a taste for grog.

In January 1827, Nathaniel McCulloch, accused of a breach of the peace in Sydney, was so contrite and humble when placed at the bar that the complainant withdrew the charge. He didn’t come to the attention of the police for another four years, but when he did, it set off an eight-year binge of drunkenness and inexplicable behaviour that eventually killed him.

1831: ACTING IN A MOST OUTRAGEOUS MANNER

McCulloch was already known as the Flying Pieman, although he was more of a terrestrial crockery agent. The origin of the nickname is a mystery – perhaps it was his noisy conduct that made people think of a hawker of baked goods.

Charge: Breach of the peace following being discovered mounted on his pony, under the verandah of a house, acting in a most outrageous manner.

As much as one would love to know what on earth McCulloch was doing so outrageously on a horse under a verandah, it was his strident reaction to the remonstrances of the complainant Captain Lamb that caused the breach of the peace. McCulloch became fractious and threatened to prosecute his accuser instead.

The Magistrate hearing the case observed that he had seen McCulloch “throwing dollars about like a madman” earlier that day. McCulloch replied that he had made £50 before breakfast and had the right to distribute his good fortune as he jolly well wished.

Allowed two sureties to keep the peace, McCulloch left the court, making a lot of rather rash remarks about how much money he had at home, and how all that cash would soon be employed to gain satisfaction from all the scoundrels who had insulted him.

He was well-known around the pubs and racecourses of the Colony as a flash type, wearing outrageous fashions, and making rash bets. One day, fully kitted out and on horseback, and “as attractive as the most superb Botany Bay exquisite,” McCulloch famously laid a bet that he would be able to ride up to Governor Richard Bourke, salute him, and receive a handshake. A bewildered Sir Richard got his salute, and McCulloch got his handshake. And for once, the Flying Pieman made some money on the racecourse.

1832 – HOW DARE YOU FLOURISH A CONSTABLE’S STAFF OVER ME?

On the right side of the law on this occasion, but only just, McCulloch decided to swear out summonses against various Sydney identities for breaching the peace, i.e., McCulloch’s peace. In particular, he was peeved at a Captain Wright of the 39th Regiment, who had flourished a staff near his head. There is no record of these complaints reaching an actual court of law.

1833 – DEBTS, “THROWN OUT LIKE AN OLD SADDLE BAG”, AND SEEKING 100 CATS

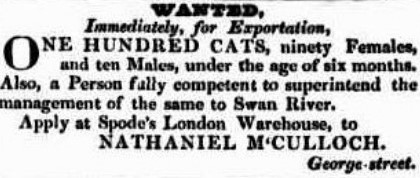

By 1833, his much-vaunted earning abilities had taken a bit of a hit. He advertised this reduction in status in a polite and respectable manner, offering liberal discounts for cash purchases. That was October 1832. In November 1832, things became very odd indeed.

How does one superintend or manage cats? What on earth was the man up to? Time would tell, but the following day, the Herald assumed that it had to do with McCulloch’s nickname.

Mr. McCulIoch has advertised in yesterday’s Herald, for ten Tom Cats and ninety Female Cuts, to meat the heavy demand of our brethren at Swan River. He will require besides, a good manager of the fraternity ; on assortment of FLYING foxes, we presume, to accompany them. Perhaps the Swan River colonists are epicures and mean to have a regular tuck-in of Cat PIE. Mr McCulloch had better advertise for these also. A MAN would, in all probability, dislike the superintendence. A monkey or a baboon would be a better overseer.

The capitals. FLYING PIE MAN. The papers mocked his debtor status with selective capitalisation, in order not to tempt his litigious nature.

One month later, in December 1833, Nathaniel McCulloch took three local identities to court for forcibly ejecting him from a dining saloon. McCulloch had been at an adjacent table in the Royal Hotel saloon and offended the Messrs Levy, Meredith and Berner. They decided to eject him from the establishment, and in McCulloch’s own words, “After throwing me down, Meredith and Levy kicked me, and Berner struck me a sly poke on the neck, they then picked me up, and chucked me holus bolus in the middle of George-street, like an old pair of saddle bags.”

It became clear during the defendants’ case that the men objected to having to sit down to dinner in the same room as the foul-mouthed and aggressive McCulloch. They were astonished at having been summoned to court by such a man. Berner asked, “Is it to be tolerated, I ask you, that we are to be thus dragged into a Court of Justice, by a fellow so notorious throughout the town, and who it is well known received fifty lashes for robbing his master’s house at Hobart Town?”

The Bench responded that they could not take notice of McCulloch’s alleged activities in Hobart. And that there were persons of “greater respectability” being taken to court all the time, thank you very much. Only one defendant – Meredith – was found guilty, and fined £5. He was told, to his evident horror, that there was no chance for an appeal. But, if any ulterior proceedings were adopted, a copy (of the depositions) might be had by summoning the presiding Magistrates.”

So ended Nathaniel McCulloch’s 1833 – debts, a plea for cats, and a small victory in court.

1834 – CROCKERY, A RUMPUS WITH A “SLAP-BANG MAN” AND INDECENT EXPOSURE

1834 began with McCulloch still (just) in charge of Spode’s, and apart from his attempted feline entrepreneurship the year before, still able to present himself as a respectable businessman. At least to those readers who had not had the pleasure of meeting him in person.

That all ended in July, when a neighbouring restaurateur, Mr Henry Farmer, tired of the effect of The Flying Pieman’s erratic behaviour was having on his trade, took out a summons to keep the peace. The effect was precisely the opposite to the one intended.

Charge: Flourishing a boiled ham, whilst making use of the most dreadful threats, imprecations and obscene expressions.

” So Mr. b_____y slap-bang man, you have obtained a summons, eh? and now I’m come to demolish the crib-I’ll summons you,” suiting the expression to the act of seizing by the shank, a boiled ham which stood near him and flourishing it about complainant’s head, made use of the most dreadful threats, imprecations and obscene expressions, which caused several persons to leave the shop. Defendant after committing a variety of excesses, seized a box of cigars which he threw about the floor and commenced dancing upon them to their absolute destruction; after which he amused himself by breaking the dishes, &c. until the arrival of conductor Price, to whom he was given into custody and finally lodged in the watch-house.

McCulloch pleaded for mercy from the Bench – he was, he promised, going to the coast of Peru, well, he would be, after he attended to his debts, and loaded some cargo for the Swan River (laughter in Court). He was placed on a good behaviour bond, but the story was all over town.

Charge: Going into the London Tavern in a state of intoxication, and while there, wantonly exposing himself to females.

The year ended with his committal for trial on a charge of indecent exposure, having erupted into the London Tavern in a state of intoxication and exposed himself to a female customer. He was released when he apologised, heartily, and the complainant withdrew the charge.

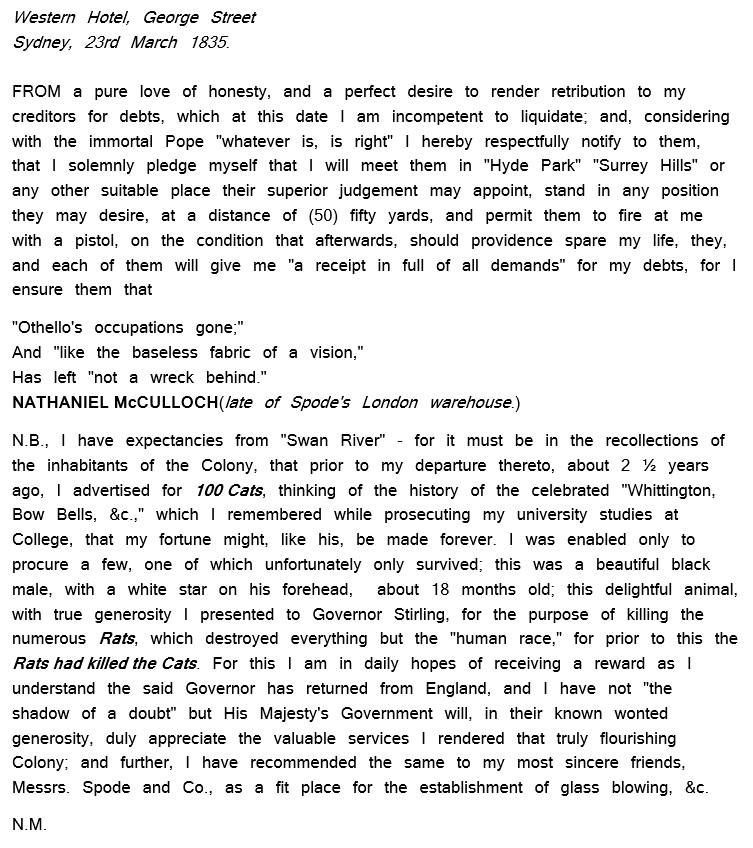

1835 – FEEL FREE TO SHOOT ME, AND IF I SURVIVE, I EXPECT A REWARD FOR MY CAT.

In February 1835, McCulloch apparently found himself in charge of an infant, which he was convinced was the child of a policeman. The mother had left it at Spode’s, and the only decent thing to do was to take it to the coppers, and demand that someone claim paternity. Of course.

THE “FLYING PIEMAN,”-An individual better known by the foregoing appellation than any other, and who has arrived at a pitch of peculiar notoriety by his eccentric conduct on a variety of occasions presented himself at the Police Office on Tuesday last, will, an infant in his arms, and loudly enquired if a certain functionary was at home, on whom the honour of paternity of the urchin had been conferred by a lady who had “chucked it” as he expressed it into his shop, and he had therefore taken it home to its papa.

The constables were directed to turn the fellow out of the office, and he went away muttering something to the effect that some people might for the future look after their own children, after such a return to his kindness and attention.

That must have been the last straw for Messrs. Spode & Co., London. McCulloch lost his business through debt and disgrace, and, in a classified advertisement, exhibited a truly strange state of mind (but explained the cats of 1833):

So, you’re offering yourself to be shot at in public, then claiming to be the Dick Whittington of Swan River. And that you will be rewarded handsomely by the Government for handing over one moggy to a no doubt perplexed local official. Clearly things were going well.

In June, McCulloch’s wife Sarah appeared in Court for drunkenness, sporting a black eye. She shared her husband’s alcoholism, and had made too many appearances in Court for her record to be ignored, and copped a three-week stay in prison. No-one thought to ask Mr McCulloch about the origin of Sarah’s black eye.

1836 – PICKING ON THE WRONG MAN AND THE EFFECTS OF DRINKING

In June, McCulloch was staggering around drunk, as appears to have been his custom since losing Spode’s agency, when he tried to detain a man named George Morris for a drunken diatribe. Morris was not amused, and at the time was carrying an iron wrench, which he used to knock McCulloch out cold. The Pieman recovered after being treated by a doctor. “We hope this will be a lesson to McCulloch and induce him to be more circumspect for the future,” remarked the Gazette.

However, it was not, and the Gazette reporter made a dire, and sadly accurate, prediction for the Flying Pieman:

Charge: collecting a mob in the streets by his riotous conduct and using obscene language.

EFFECTS OF DRINKING-On Thursday Nathaniel McCulloch, well known as the “Flying Pieman,” and who has long been a pest to Sydney from his drunken habits and filthy language in the streets, was placed at the bar of the Police Office in a most tattered garb, and trembling in every limb from the effects of inebriation and his head bound up to hide a ghastly wound received in a drunken row, charged with collecting a mob in the streets the overnight by his riotous conduct, and using obscene language. The Bench sent him to gaol for a month as he could find no one to become bail for him to keep the peace. A few years since this man was the proprietor of a good business and kept his horse and gig. Here then is a living witness (as there are but too many in this colony) of the destruction and ruin wrought by the baneful habit of intoxication; all moral principle is thrown aside, every social bond broken, and lost to himself, and a nuisance to his follow creatures, the habitual drunkard sinks down to his grave dissipated and alone.

1837 – ARE YOU MAD OR DRUNK?

Charge: Assault committed upon, and insult offered to, Colonel Wilson.

A month in gaol sobered McCulloch, but only temporarily. He returned to his use of ardent spirits, and found another passer-by to mock and harangue. This time it was one Colonel Wilson, who fortunately was not armed with a wrench.

Yesterday morning, as Colonel Wilson was walking through the Sydney Market place, the notorious McCulloch, alias the Flying Pieman, thought to amuse himself a little at the Colonel’s expense. In one hand he flourished a hunch of radishes, in the other a bundle of shallots, from each of which he occasionally took a mouthful; perceiving the Colonel, he made up and willfully pushed against him. “Are you mad or drunk,” enquired the Colonel; ” Mad, mad, by-_____,” said the Pieman. “Then take him to the watch house,” said the Colonel, and he was secured. Upon his being taken into custody, a number of what are termed flash notes, which he is in the habit of sporting, with a view of making himself appear a man of property, were found in his pockets.

Mad, mad, by God, indeed.

Colonel Wilson showed mercy when McCulloch appeared before him the following day. The Pieman received a lecture, a reduction in the charge and was only fined 5s. for being drunk.

1838-9 A DEFEATED MAN

McCulloch was a defeated man by this stage. Admitting to harassment was an acknowledgement he would not have been capable of in his prime. In August, he attempted to take his life by cutting his throat with a dinner knife, then running into the street, creating a sensation. It was a minor wound, and he was detained and hospitalised.

The following year, McCulloch succeeded in ending his life. He was again very drunk and stabbed himself in the throat. This time his wound looked serious.

His wife was so upset with him that she refused to put a blanket over or under him while he was being taken by cart to the Hyde Park Barrack prisoners’ hospital. She told bystanders that her husband had “used her dreadful.”

On his journey to the hospital, McCulloch cried “Oh! I am nearly gone, Constable; I was in liquor, or I wouldn’t have done it.”

Several hours later, he was dead. At the inquest, the doctor disclosed that his death was due to apoplexy (a stroke), brought on by drinking. The neck wound was serious, but by itself was not fatal. The Flying Pieman was barely forty.

In the following few days, journalists waxed pious about his drinking and riotous nature, although some recalled him in his prime. But time moves on, and almost immediately afterwards, William King became known as the Flying Pieman – he did, after all, sell pies – and the man who had progressed from convict chains to running a successful business, to ruin and drink, faded from history.