In January 1848, Captain Wickham, Government Resident for Moreton Bay, received a letter from the Colonial Secretary’s Office in Sydney, ordering the closure of the Convict Hospital at Brisbane. The result was that everyone and everything had to go – patients, paupers, medicines, furniture – the lot. What couldn’t be sold was to be shipped to Sydney, thank you very much.

Our humane and tender-hearted Government sent by the last steamer a peremptory order for the discharge of the patients lying in the General Hospital on the 31st ultimo. They were accordingly turned out of the building to seek refuge in the hour of their distress wherever they could on Monday last. Some of the poor creatures could scarcely crawl, and it was really pitiable to witness their sufferings on the occasion. Had it not been for the kindness and humanity of some of the inhabitants several might have perished in the streets.

Moreton Bay Courier, Saturday 5 February 1848

It was not the first time that the Convict Hospital had been ordered to close. It had been operating on sufferance since Moreton Bay had been opened to settlers in 1842. This particular act of bureaucratic cruelty, forcing invalids out into the street, led to the creation of the Brisbane General Hospital, as a group of enterprising early Brisbane citizens worked to find a solution that would allow the sick and injured free settlers of Brisbane to be treated.

The Convict Hospital

The Convict Hospital was built by convicts around 1826, part of the public works program run by Commandant Patrick Logan. It was staffed by the very young Dr Henry Cowper and a small team of convict workers. All materials and medicines were sent from Sydney – grudgingly and sparingly. Cowper, in addition to tending to hundreds of convicts, had to account for every item used, and beg the Colonial Secretary for replacements. Little wonder that he became profoundly anti-social – a heavy drinker, smoker and user of some fairly disgusting language.

After Commandant Logan’s murder in 1830, the health of the convict settlement improved. Food rations were increased, floggings were reduced, and running the hospital became less arduous. Stores and facilities were still painstakingly recorded for the Colonial Secretary, and the only patients were convicts, soldiers and their families. It was all highly ordered and everyone knew their role – until 1842, when free settlers arrived.

There were still convict servants, ticket of leave holders and soldiers about, and the hospital was reserved for their use. Apparently no-one in Sydney had considered what would happen when free people required hospital treatment, particularly if they couldn’t pay.

In March1843, Captain Wickham, newly installed in the tiny settlement, was informed for the first time that the hospital would be closing at the end of the month. The Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals had recommended it. Any convicts or soldiers still sick were to be sent to Sydney. Wickham and Colonial Assistant Surgeon Dr David Ballow wrote urgent missives to the Governor. There were convicts with fever being treated in the hospital – an epidemic had broken out – it was unsafe to send them to Sydney by sea, and what of the settlers who used the hospital?

Wickham, during the delays between official instructions, decided to instruct Ballow to keep the fever patients in the hospital and continue treating them. As March wore on, Wickham and Ballow waited for instructions.

By the end of the month, they had them. Governor Sir George Gipps ordered that the hospital could remain open for soldiers and convicts only for the time being. Patients not in Government employment were not to be admitted. Further, would Wickham please furnish returns of the number of persons admitted since January 1st, distinguishing between soldiers, convicts in Government service, convicts in private service and paupers? Immediately?

This was furnished quite promptly, setting off a further demand for an account of the fees extracted from those not in Government employment. Wickham and Ballow duly came up with the figures, and were given grudging permission to keep the hospital open at least until assigned convict workers could be removed from Government service at Moreton Bay.

In August 1843, Wickham and Ballow again wrote to the Colonial Secretary, setting forth the reasons for maintaining what they now referred to as the General Hospital at Moreton Bay. This time, they managed to convince His Excellency, using the best weapon available – money. The private contributions were deemed to be “considerable.”

Sir George authorised the continuation of the hospital, and permitted the treatment of free patients – by free patients, he meant non-convicts or free settlers. No persons were to be admitted without paying.

In the following months, Commissary stationery supplies in Brisbane and Sydney Towns were taxed to the limit as official correspondence steamed north and south – largely about the hospital, but also such vital administrative matters as whether the Pilot at the Bay should draw rations of tobacco and sugar, or whether he should just receive a payment in lieu.

The Colonial Secretary, instructed by Governor Gipps, was much occupied by the question of fees. Having discovered, to its great surprise, that a free settlement contained free settlers who might require medical attention, the Government set about demanding accounts.

When further apprised of the existence of people who could not pay for their medical treatment, a form of administrative panic set in. Who were these paupers, and how many of them had received treatment? Why had paupers been treated? How was the treasury to be recompensed? How were the fees being collected from non-paupers? Could this be happening at other Convict Hospitals? It was all very taxing.

Once statistics had been called for and collected, and forms created and distributed, the issue of paupers and reluctant fee payers remained. Respectable citizens entered into bonds for the treatment of pauper patients, and those were forwarded to Sydney. It was a time-consuming bureaucratic business, but Governor Gipps was absolutely unmoved. No free settlers without fees. By October 1843, he had even set rates – paying patients at 3 shillings a day (a little high, he admitted, but necessary to keep the numbers down), and paupers could cough up 1 shilling ninepence per day, and not a penny less.

Benevolence

Unsurprisingly, the Moreton Bay Benevolent Society was founded in 1844, as a citizen-run charity. Wickham and Ballow were prominent members of the committee. The Benevolent Society sought donations from those who could spare them, and channeled them to the paupers, elderly and bereft as best they could.

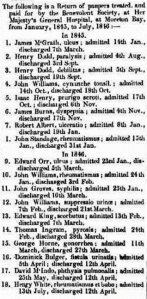

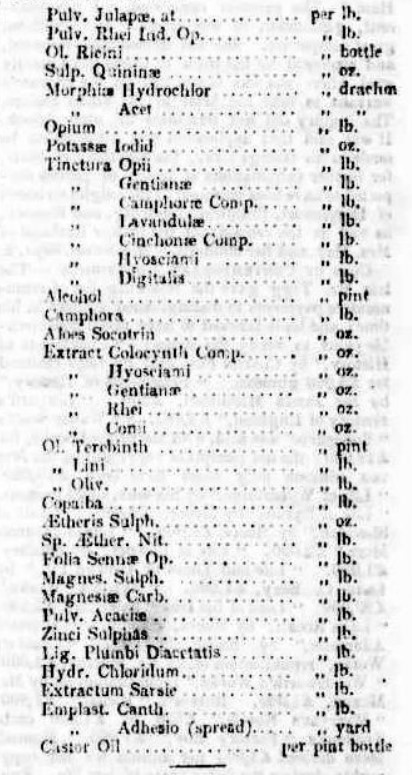

As a public charity, the Benevolent Society had to give public account of their endeavours, and the following list was duly published for all to read.

I suppose that having your medical treatment covered by the kind souls of the Benevolent Society was some consolation after having the exact nature of your medical condition published in the Courier. Good luck explaining a couple of those conditions to the missus.

Regime Change

While the Moreton Bay General Hospital and the Benevolent Society struggled on, Sir George Gipps became ill. He was replaced on 3 August 1846 by a very different figure of a man – Sir Charles Augustus FitzRoy. Governor FitzRoy owed his surname to his aristocratic and royal connections, as a descendant of Charles II and his mistress Barbara Villiers, a Lady of the Bedchamber, who took her duties very literally. Her children were acknowledged, and given the surname FitzRoy (Fils-Roi). Fitzroy adopted a more conciliatory approach with the local grandees, who were awed by the presence of someone who combined royal blood and good head for Government business.

Fitzroy’s presence did not deter the indefatigable Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals, who in late 1847 again recommended the Moreton Bay Hospital’s closure on the ground that convict transportation had ceased. The message was sent to Captain Wickham in Brisbane in January 1848, and the turn-out occurred. Fitzroy signed off on this – the correspondence was noted “C.A.F.” and “approved.”

Wickham and Ballow were aware that they were dealing with a different kind of Governor, as well as a different Moreton Bay. There were more inhabitants, roads were being opened up, and there was a local newspaper up and running. Having anticipated the closure order, they had a plan for the future. The closure was brief.

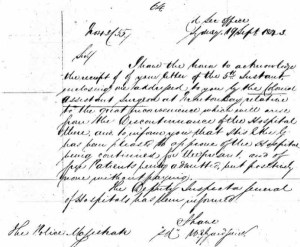

I am directed by His Excellency the Governor to inform you that here will be no objection to give the Building over to a Committee of Gentlemen for the benefit of the District in the event of it being proposed to establish a Hospital with the assistance of voluntary contributions – and to leave with the Committee the Surgical Instruments, stores etc now belonging to the Hospital. I have therefore the honour to request your further report.

Edward Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary’s Office, April 1848

Thus, the Hospital was allowed to remain open and kept its supplies, while a Committee of Gentlemen was formed, met, and began working towards the creation of a General Hospital for the public. The Gentlemen who assembled were:

Captain Wickham, Mr. E. B. Hawkins, Mr. C. Mackenzie, Mr. Lyon, Rev. B. Glennie, Mr. G. S. Tucker, Mr. J. Richardson, Mr. Haly, Mr. J. Kent, Dr. Cannan, Mr. Francis Bigge, Mr. G. Burgoyne, and Mr. Grenier.

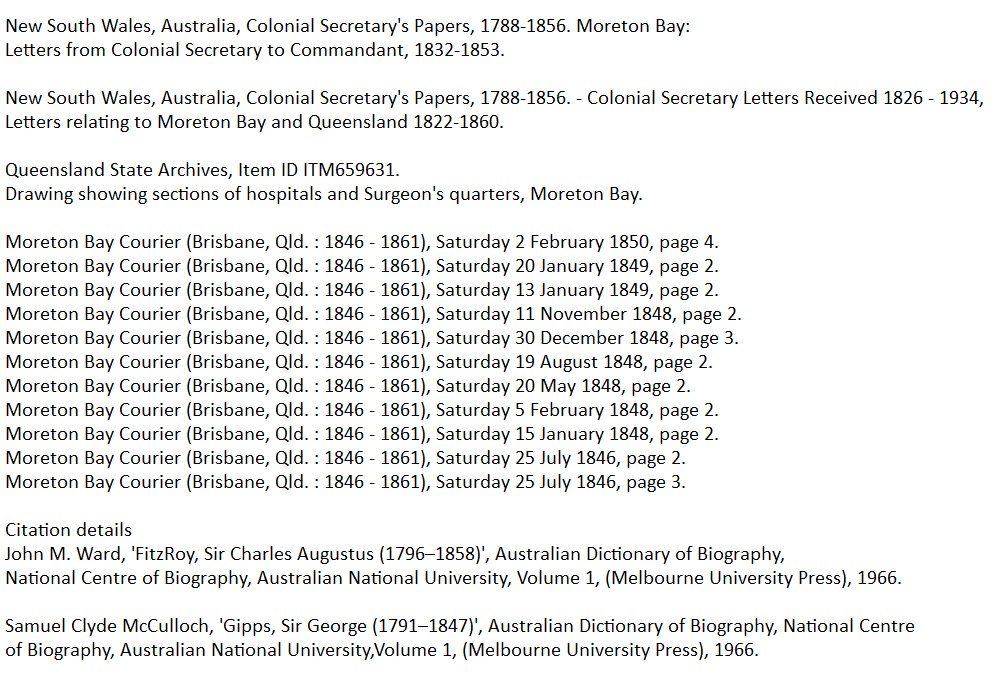

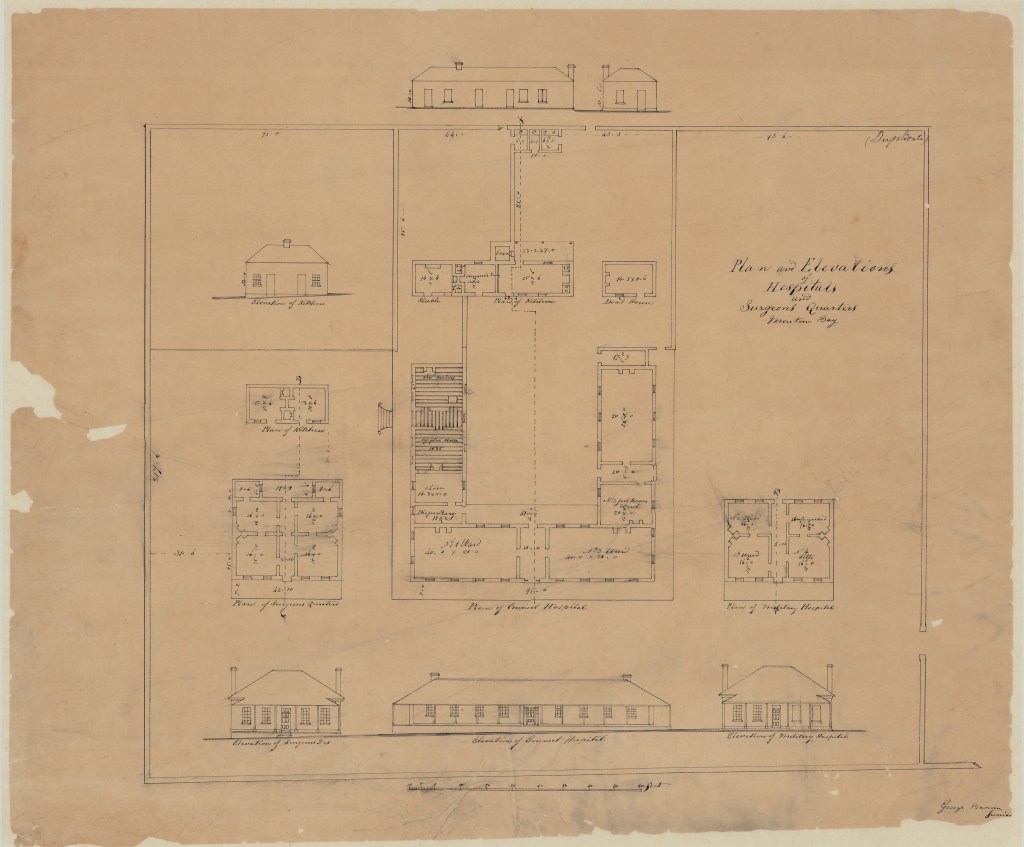

Convict Hospital Floor Plan

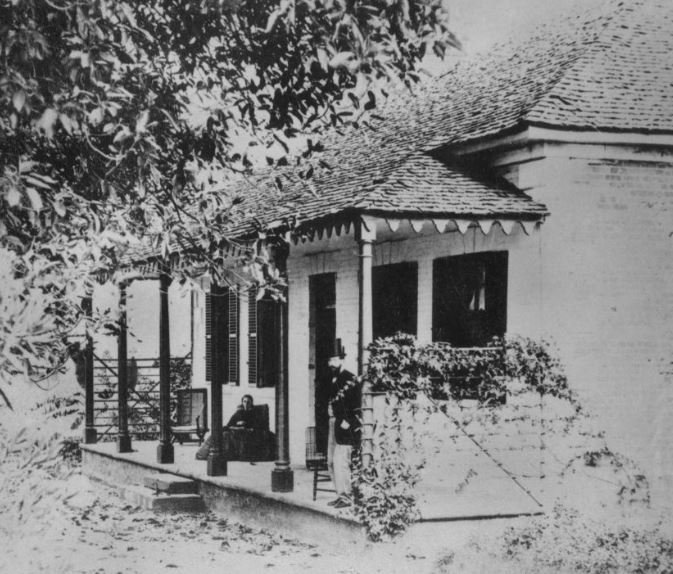

Surgeon’s Cottage, c.1860

Rare photo of old Brisbane General Hospital

As 1848 progressed, so did the preparations for the General Hospital. The Committee was given the Colonial Secretary’s permission to merge with the Benevolent Society, then to appropriate fines from the Brisbane Court of Petty Sessions for additional funding. The Government would match subscriptions, if they reached the total of 200 pounds per annum. Subscriptions were sought, and although a little slow in arriving, a blitz of passive-aggressive classified advertising managed to open the pockets of the reluctant.

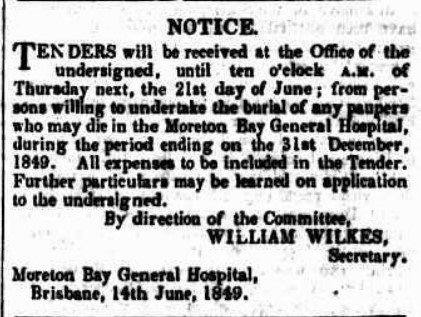

William Charles Wilkes, “Our Windmill Correspondent,” was elected Secretary of the institution, and set about calling for tenders for supplies and services as diverse as water tank construction and pauper funerals.

A MEETING of the contributors to the funds of the MORETON BAY DISTRICT HOSPITAL is hereby convened for twelve o’clock (noon), on FRIDAY, the twelfth day of January next, at the Court House, North Brisbane, for the purpose of electing Officers for the abovenamed institution, to serve during the year 1849, in accordance with the terms of the Act of the Governor and Council of New South Wales, 11th Victoria, No. 29.

By, order of the Committee, WILLIAM WILKES, Brisbane, Dec. 23,1848. Secretary pro. tem.

“The graves must not be less than five feet deep, and the bodies must be removed at such times, and under such directions, as may be named by the Surgeons.” Just in case anyone wondered.

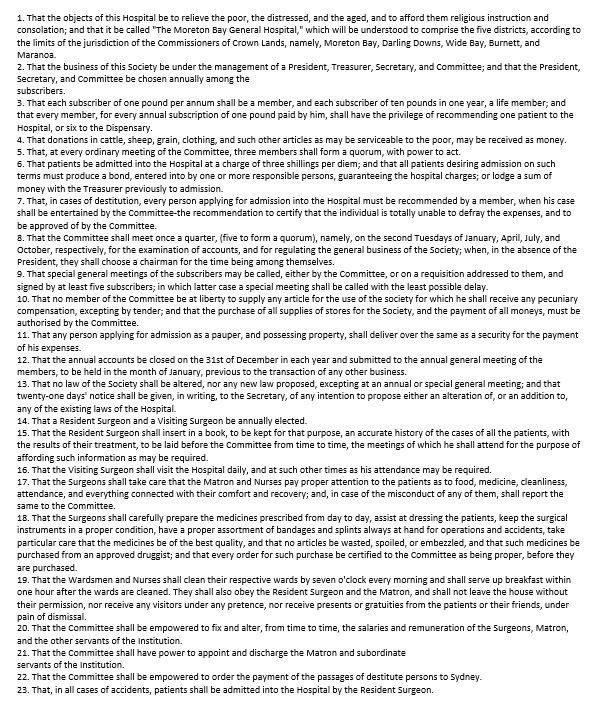

After a year of planning, negotiation, fundraising and tendering, the Brisbane General Hospital was proclaimed on 12 January 1849. Here are the original rules:

Sir Charles FitzRoy was quick to allow the handover of the hospital and stores to the clearly prepared local officials. Unlike his predecessor, he did not hector or obstruct Wickham and Ballow about the plan to replace the Convict Hospital.

Ironically, transportation to Moreton Bay resumed – mercifully briefly – in 1849, with the arrival of the Mountstuart Elphinstone. Once again, FitzRoy allowed himself to be swayed, this time by the authorities in England, only to rescind the policy and emerge looking like a very able administrator. Perhaps it was a strategy.