For a place with a lot of prisoners about, and a population fond of indulging in ardent spirits, Moreton Bay was sorely lacking in a place to house criminals. There was a small lock-up in the Police Station, which occupied a part of the former Convict Barracks. It was only suitable for very short stays, and did not hold more than a couple of people.

Free settlement began in 1842, ending the old system of prisoners being brought up before the Commandant and handed lashes (in the case of the men) and time in the cells on bread and water (for the gentler sex). The last entry in the Moreton Bay Trial Book is from February 1842, when Commandant Owen Gorman dealt with Jane Appleyard, a prisoner of the Crown in the assigned service of Andrew Petrie, for being drunk and disorderly at her place of work.

The same lack of foresight that informed the eight-year struggle to keep the hospital open kept Brisbane without any place to put convicted criminals until 1850. Captain Wickham, amongst his many other duties, furnished a return of persons who entered the lock-up at Brisbane from January to December 1843: 85 free persons, 109 prisoners of the Crown. Perhaps His Excellency and the Colonial Secretary were profoundly optimistic, and thought that crime might just decrease to practically nothing with lots of nice free settlers coming into the area. At any rate, the place wouldn’t need a gaol – surely?

Sadly, this was not the case. In December 1845, Captain Wickham wrote to the Governor, asking if perhaps His Excellency might consider repairing the Female Factory and converting it into a gaol, as the lock-up cells were not adequate to house convicted and remanded prisoners. The building existed, and repairing it would be the least expensive option.

No dice.

I am at the same time instructed to appraise you, with reference to your observation respecting the Female Factory, Post Office and House adjoining the Commissariat Officers Quarters, that the Governor has no funds applicable to the repair of these Buildings.

The Female Factory remained on the table in negotiations for the next few years, and it had an interesting history.

The old Female Factory.

The Female Factory in Queen Street was erected in 1829-30 and was used to house Brisbane’s female convicts until 1837, when all the women were moved to a more rural Factory in Eagle Farm to escape the avid attentions of the male convicts and soldiers.

The Female Factory had a structural quirk – it was rather easy to break into. (Few had tried to break out – it was probably safer for the women to be locked up.) Dr Cowper had ended his career in 1832 by gaining admission to the Factory and getting drunk with a few of the inmates. In August 1836, a Corporal McDonald was looking about the Factory for one of his own men, whom he suspected of being somewhat too interested in the contents of the structure, when he saw the inelegant figure of Chief Constable Bottington employing “an ingenious ladder” to clamber over the walls. He put Bottington in the cells, and notified an appalled Commandant Foster Fyans of the night’s events.

Fyans sent Bottington to the Pilot Station at the Bay to await the first transport back to Sydney, and ordered four bushels of broken glass from the Sydney Commissariat, with which to decorate the top of the walls of the Female Factory. It was the only way, he considered, to keep interlopers from breaking in. His Excellency the Governor regretted that he could see no means of punishing Bottington, but would make sure that the Sydney Police did not employ the man. In the meantime, could Fyans in future please order broken glass in the correct manner? “Your attention is more particularly drawn to the 1st and 2nd article of the Government Notice of the 4th October 1836 respecting requisitions.”

Fyans got his broken glass, despite his lack of proper Ordnance protocol, and removed all but the 14 oldest ladies from the Factory. That would be deterrent enough for the local lotharios, he thought. However the cost and inconvenience of two separate female establishments, one for 14 people, soon led to the abandonment of the Queen Street factory in favour of the newer Eagle Farm Agricultural Factory.

Apart from the few miserable months the Petrie family spent in the Queen Street Factory in 1837 while building their home, the Factory was left empty and successive administrators did not have any funds available for its upkeep.

“The Slow-Coaches of Sydney.”

Nearly a year went by after Captain Wickham’s submission, when a keen-eyed journalist noticed in the Estimates for 1847 that £820 had been set down “for the building of a gaol at Moreton Bay.” In the Estimates debate, Mr Lowe asked if the resulting gaol wouldn’t be rather small? Like the outlay? The Colonial Secretary replied smugly that there were several large public buildings in Moreton Bay, and the sum was to repair them. As if it had been his idea all along.

1847 also saw the beginning of Petty Sessions at Brisbane, and their Worships found themselves occupied largely with the Masters and Servants Act. Numerous masters found their convict servants to be insolent, drunk, lazy or missing in action. Said servants found themselves sent to Sydney for stays of 7-14 days in the gaol, because there was nowhere to imprison them in Brisbane. An all-expenses-paid steamer journey, a week or so in durance vile, and they would be unleashed, to their great delight, into the well-established city in the south. Convict insolence in Moreton Bay began to reach epidemic proportions.

And despite the fond hopes of His Excellency, serious crime occurred and increased in Moreton Bay as its population rose. Having established Petty Sessions, the need for Quarter Sessions and a gaol became pressing.

“Twelve months have now lapsed since the Council voted upwards of £800 for the repairs of the Factory Gaol in North Brisbane, and the work has been delayed in consequence, we understand, of Mr Lewis neglecting to send the plans and specifications for the alterations required.”

The Moreton Bay Courier, Saturday 31 July 1847.

Mr Lewis was the Clerk of Works in Sydney, and Mr Lewis was in a spot of bother as his under-staffed department struggled with the demands of the vast and growing Colony of New South Wales.

At length, a Mr Hill of North Brisbane won the tender to effect the repairs, and work began in November 1847. Slowly.

A full year after work began, it became a local sport to find a vantage point and see if anything was happening at the site.

From his lofty perch on Wickham Terrace, the Windmill Correspondent gazed down at the township and on October 28, 1848 was moved to both prose and verse when he spied some activity at the Factory.

I have lately amused myself by sitting on the semaphore and watching the progress of events in the distant capital. While so engaged this day, I noticed a circumstance so unusual, and of so exciting a character, that I thought it my duty to communicate the same to you immediately, by extraordinary telegraph. A man was at work at the new gaol! The event had such a powerful effect upon me that I immediately wrote the following lines on the crown of my hat, with a piece of chalk which I had previously abstracted from my landlord’s counter for private reasons:-

In January 1849, sections of the gaol wall were seen to be adorned with chevaux-de-frise, and disbelieving locals were told that the repairs were nearly complete. Mr Lewis and/or Mr Hill were not minded to put them on all the walls, though, and it was noticed that there were plenty of smooth shingled areas that would afford easy passage for an inmate seeking freedom.

And then, nothing happened. The gaol stood empty for months. The works had to be certified, and that involved getting the Colonial Architect to come from Sydney to inspect them, and then have the gaol officially proclaimed. In April 1849, a Mr Paton of the Colonial Architect’s office, arrived by steamer and pronounced himself satisfied with the job done. He was prepared to certify the Brisbane Gaol.

And then, more nothing happened. Insolent convicts were still getting a free 500 mile steamer trip to Sydney to spend a few days at Darlinghurst Gaol, although the local Magistrates were getting wise to the scheme. By mid-1849, convict servants were being given longer prison terms than their offences actually deserved, meaning that a fair stretch of time had to be served before they could get out and enjoy the bright gas-lights of Sydney Town.

A petition from Brisbane in August 1849 didn’t help matters – the gaol was not proclaimed, despite the information that Quarter Sessions were due to commence in Brisbane in early 1850. The Courthouse at Brisbane would require upgrades in order to receive His Honour the Chief Justice, but unsurprisingly, none appeared to be forthcoming.

But a few days remain of the present year, and the gaol is not yet proclaimed; the appointments of, the Sub-Sheriff, Judge’s Clerk, or the officers of the prison, are not notified; and nothing has apparently been done towards refitting the Courthouse, which will require extensive alterations before it can be used for an Assize Court. It is surely time that a little activity was displayed in these matters. The money has been voted for payment to the officers of the gaol from the first of next month, and we have reason to believe that repeated applications have been made to have the necessary alterations made in the Courthouse.

Moreton Bay Courier, 15 December 1849

New year, old gaol.

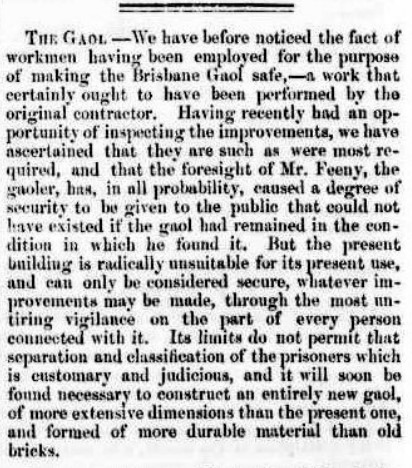

In January 1850, more activity occurred in the gaol precinct than had happened in the entire previous year. The Superintendent, Martin Feeney, arrived with two turnkeys (warders). Feeney and his men looked over the gaol, and found it was dangerously insecure. More repairs were required to make it secure – like, say, more bars on the windows. John Petrie’s opinion was sought, obtained, and money very reluctantly forwarded from Sydney after repeated resubmissions over a period of months.

On 13 May 1850, Justice Therry opened the Supreme Court at Moreton Bay. He gave a reasoned and stirring address to the locals, before setting about the business of putting quite a few of them in the renovated Brisbane Gaol building.

The case of Wagner and Fitzgerald was perhaps the most sensational of the first sitting. They were accused of the shooting and bludgeoning death of James Marsden (aka Charles Martin) on a station at Wide Bay. They were found guilty, and sentenced to be hanged at the Brisbane Gaol.

The inhabitants of Brisbane were horrified to learn that an execution would occur in the heart of their town. Public executions simply didn’t happen here. Well, not since free settlement. Very few locals would have been around when Mullan and Ningavil were hanged at the Windmill for the Stapylton murder a decade before, fewer still when Fagan and Bulbridge were hanged in December 1830. A petition was forwarded to the Executive Council, praying that the sentences not be carried out, but was refused.

The scaffold was built near the public road, to the further horror of residents. The condition of the gaol yard meant that the gallows had to be put up on what is now the footpath outside the General Post Office. When the men were executed on the morning of July 8, 1850, there were fewer witnesses than anticipated.

In all, eight men were hanged at the Queen Street Gaol – three were Europeans, one was Chinese and the other four were Indigenous men (including the warrior Dundalli).

Perhaps a new gaol would be a good idea?

The Gaol was open, staffed and receiving guests, but it was clear that the guests were in danger of leaving early, due to the crumbling old bricks of the walls, and the length of time it was taking to complete the repairs.

The first break-out attempt was in April 1851, when officers became suspicious of furtive activity in the wards, and found that one of the ceiling beams had been nearly sawn through. A crude saw, wrench and blanket ropes were discovered, and the prisoners suspected of doing this were put in heavy irons.

An investigation was held at the gaol before Captain Wickham and Mr Ferriter, JP, and it managed to also uncover ill-feeling between the Principal Turnkey Richard Allen and the Gaoler Martin Feeney. The Visiting Justice was briefed to investigate allegations that Feeney was drunk in the presence of turnkeys and abusive to the Matron of the Gaol. The Visiting Justice was unable to establish whether Feeney had been guilty of intemperance and abusive behaviour. Other witnesses on staff gave evidence that it was Allen’s attitude and drinking that had caused the breakdown of relations. So much ill-feeling was exposed in the course of the investigation that it was recommended that Allen be dismissed. The Sheriff was directed to inform Mr Feeney that if another instance of intoxication was brought to his attention, Feeney would also be dismissed.

His Excellency, Charles Augustus Fitzroy, read through the depositions and report relating to the attempted break-out with irritation. He decided that the fault lay with the gaol officers -they showed a “want of vigilance.” As for the never-ending requests for repairs to the establishment, he made a marginal note: “Captain Wickham to be reminded of his recommendations re converting the Factory into a Gaol.” Said reminder was duly administered.

Eventually, the Colonial Architect was ordered to send an officer to Brisbane to inspect the gaol and provide a report on the viability of repairing the gaol or building a new one, bringing the issue of the Brisbane Gaol full circle.

The Queen Street establishment struggled along for the rest of the 1850s, enduring disease, maladministration, escapes and escape attempts, until His Excellency was forced to consider a brand new gaol for Brisbane. Happily for the Government in Sydney, this process took so long that the new Gaol at Petrie Terrace was completed and opened by the newly-separated Colony of Queensland. Henceforth, any prison problems were entirely our own.