Part 1 of Tom Dowse’s Memories of Old Brisbane

(Originally published in the Queenslander on 24 July 1869.

IN those days—happily long since passed away—when the parent colony of the Australian group enjoyed the unenviable distinction of being the only penal settlement on the shores of New Holland, it was found from time to time necessary to push out from her midst other settlements on the eastern coast, for the purpose of getting rid of that portion of her criminal population, which the terrors of the lash, the chain gang, and the gallows had failed to restrain from committing fresh crimes. Thus, in reading the early history of New South Wales, we find that but a short time after Governor Phillip landed at the head of Sydney Cove, in the harbor of Port Jackson, it was found necessary for the peace of the new settlement to cast out from her midst the turbulent and irreformable portion of her felon population. Thus, we find various localities from time to time taken up, upon which settlements were established. The first on the list is the Coal River (Newcastle) ; the second, Port Macquarie; then, I believe, Norfolk Island; and, finally, in 1823, Moreton Bay. As it is with the latter settlement we have to do, I will refrain from dwelling upon this not very interesting subject, further then just stating that in 1824 a draft of convicts and a large military detachment was despatched from Sydney and located in the first instance at Redcliffe Point— a headland lying about six miles north-east of the present village of Sandgate.

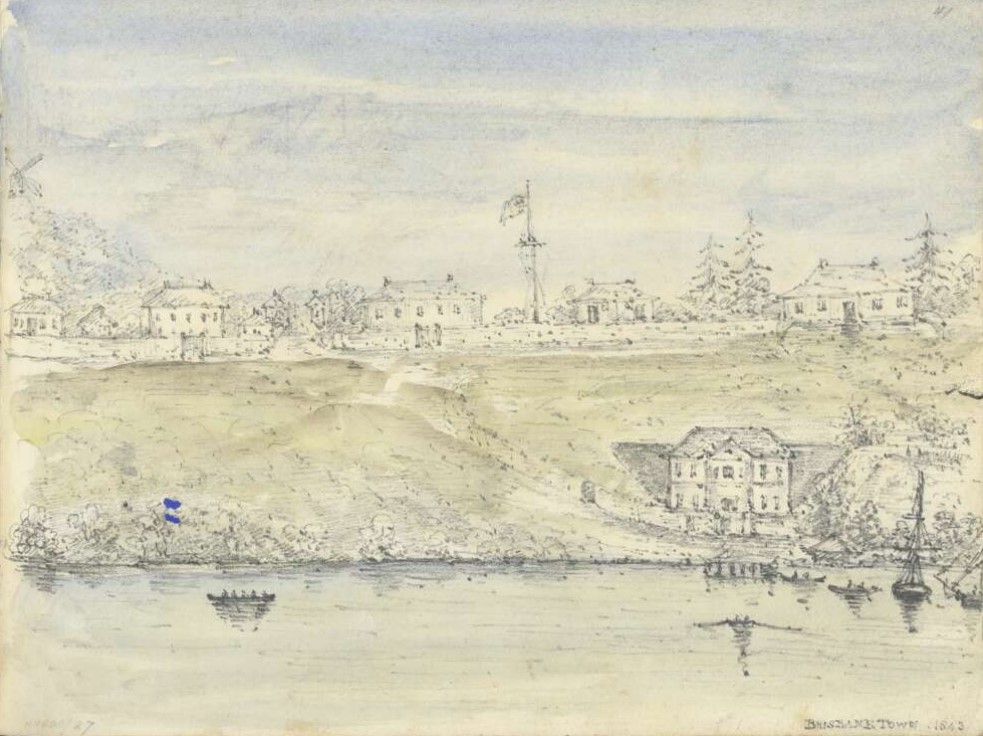

The unhealthiness and general unsuitableness of Redcliffe necessitated the authorities to look out for another clearing; and for that purpose, the adjoining country was surveyed, and finally the present site of Brisbane was fixed upon as the future settlement. Under the energetic supervision of the Commandant, Captain Logan, very important public works were undertaken. For instance, the old Commissariat Stores bears the date of erection, 1824, on its front; the convict barracks, military barracks, officers and official quarters, all appear to have been rapidly brought into existence under Captain Logan and his successor, Captain Clunie’s, government.

Thus, when the pioneer squatter began to follow up the discoveries of the lamented Allan Cunningham, and migrate with their flocks and herds to the Downs country and below the eastern slopes of the Main Range, the penal settlement established on the waters of the Brisbane River some fifteen or sixteen years previously, had began to assume the importance of a town—the roads leading through and above the settlement having evidently been laid out with that end in view.

Queen-street had been judiciously laid out a chain and a half wide—that is, taking the line of the old Post-office lumber yard, lock-up, and barracks, forming one side of the thoroughfare, and the various plots of ground opposite, used, I understand, as gardens for the non-commissioned officers, and others employed in the service of the Government. The road, also, running parallel to the river, and leading to the commandant’s quarters, now William-street, had been left, very judiciously, a good width; but, unfortunately for the future of the city, Governor Sir George Gipps, on his visit to these districts in the early part of 1842, directed the surveyor, in laying out the streets of Brisbane and Ipswich, to confine the width of the streets to one chain. The inadvisability of this step has been apparent ever since. Yet it is somewhat remarkable that in recent days our present Surveyor-General has committed, in too many instances, the same blunder.

But to go back : In 1842, the settlement of Moreton Bay was thrown open by proclamation to the occupation of the general public ; and a number of Sydney men availed themselves of the opportunity of viewing the promised land, and on their return the results of their investigation were such as to induce numbers of land sharks and speculators to attend the first sale of town lands in the town of Brisbane, and at the land office in Bent-street, Sydney, run up the allotments submitted to auction to rather burn-finger prices. The land sold at that auction, held in July, 1842, consisted of one section only in North Brisbane—namely, that section comprised in the area formed by Queen, George, Elizabeth, and Albert streets; and two or three sections on the south side of the river. But the disastrous effects of the commercial crisis of that and the previous year had so revolutionised business matters in Sydney that most, if not all, of the allotments sold on that occasion either became forfeited or changed owners subsequently at very reduced prices. As an instance of the uncertainty of land speculations in that day, the allotment at the corner of Queen and George streets, occupied by the New South Wales Banking Company, sold at the sale in July, 1842, for about £450. The purchaser failed to pay up the balance of the purchase-money within the month, and the land become forfeited, and reverted to the Government. That same allotment was again offered at public sale, and disposed of at the upset price of £26 (twenty-six pounds). It passed through various hands, who improved the property, and finally became the property of the present proprietors, at a value about the cost of the buildings at the time erected thereon.

With these preliminary remarks, as we say when on the stump, permit me to give my readers a short epitome of my first night in the “Settlement.” Cold and weary with long sitting, hungry from last fasting, behold me and my fellow voyagers in the little schooner Falcon, of and from Sydney, Captain Johnny Brown, master, landing from the pilot boat which had brought us all up from the Pilot Station at Amity Point, on a makeshift wharf nearly opposite the Commissariat Stores. The night had set in before we entered the river, having had to contend against a strong S.W. breeze across the bay. It may be, there-fore, set down as an established fact that when we shook ourselves together on the old wharf, about 8 o’clock in the evening, we were not exactly the parties competent to be called upon to express an opinion upon the beauties of the river, or the natural advantages of the Settlement.

Amity Point

The Wharf

Commissariat Store

On the contrary, my friend the skipper said something about his eyes and limbs that did not convey a blessing to himself or to his hearers. But it was cold; and one could hardly avoid being uncomplimentary when it is taken into consideration that we left the comfortable quarters of Jemmy Hexton, the old pilot at Amity Point, about 4 a.m. that morning without breaking one’s fast, and, with the exception of a slight feed on the voyage, had not been able to keep up the necessary carbon to keep the inner man comfortable. In fact, we had all been the victims of misplaced confidence. We had expected to land in Brisbane in about eight or ten hours—having a good boat and crew— instead of which we had nearly doubled that period of time. After all, my first night in the Settlement was a caution to croakers.

Let me describe scene the first:— A portion of the southern wing of the old Barracks, converted, by the ingenuity of the lessees, from a dirty, dreary kitchen or cook-house into a snug and comfortable stores and dwelling place, in which, on the night I made my first appearance therein, I found, with my brother-in-law the skipper, a hearty welcome from the worthy occupiers—namely, Messrs. John Harris and Richard Underwood, trading in the new Settlement under the style and title of Harris and Underwood, general storekeepers. The company at the supper table consisted of the firm and their ladies, an old gentleman named White, then acting as Postmaster and General Inspector and Superintendent of the Ticket-of-leave Constabulary Force stationed in Brisbane, the captain of the schooner Falcon— familiarly known amongst old colonials as Johnny Brown—and Old Tom, without the frosty pow.

The amusing anecdotes of passing events given with much zest and humour by our hosts,’ and their graphic particulars of life in the Settlement, coupled with those social appendages which, I believe, to this day are profusely placed on the hospitable boards of those gentlemen, kept us visitors in high good humour, and very much helped to thaw our stagnant blood, and make us have a better opinion as to the future of the young community. Before this scene passes away, let me for a few moments recall to memory some of the anecdotes relating to ” Old Times,” and in connection with one of those that sat with me round Messrs. Harris and Underwood’s mahogany.

Old Mr. White, the first man of letters in Brisbane—good old soul, who can forget his hospitable manner of receiving the jackaroo squatter—whose advent, perhaps for the first time to the Bay, was not only to receive and forward supplies to his station, but to obtain the much-prized letters from home. But the unique management of the postal service under the directory of old White was something to remember as an instance of the unsurpassing value of this old trump. I will repeat an anecdote related to me by a gentleman who had occasion to visit the Settlement just previous to the removal of the convicts.

This squatter had come down from the table-lands with his team, to obtain supplies for his establishment, and after unyoking his team on the south side of the river, came over to obtain his letters. Calling at the Post-office, then kept in the old brick house at the corner, and still forming a portion of our present postal department, he found the worthy distributer of letters busy discussing with two other gentlemen the relative merits of red and white tape —vulgarly known as rum and gin. Upon asking for his letters, he was politely requested to take a seat, and help himself from the black jacks standing on the table. Before availing himself of this kind invite, he again asked for his letters. The reply was, “Oh, stuff! sit down, and we will look for the letters by-and-bye.”

Towards 11 o’clock the other two visitors left, to proceed to the Commandant’s quarters, where they had been invited to lunch. Another attempt was then made to get the long-coveted letters; but no! the old gentleman seemed to consider the question of correspondence a matter of no moment and insisted upon my informant going with him to dinner, at Mr. Andrew Petrie’s. Finding that it was better to make a virtue of a necessity, the invitation was accepted, and at the hospitable residence of the Clerk of Works the disappointed letter seeker spent a very pleasant afternoon. In the meantime, the postmaster had hooked it, and on my informant going again to the Post-office, found it, although only 4 o’clock, closed for the day, and the man of letters not come-at-able. Going round to the rear of the premises, my friend enquired of the servant, one Peter Glynn, what he should do to get his letters. “Is that all you want?” says Peter. “Come in; I will manage that.” Going into the bedroom and bringing out a bunch of keys, he opened a large bureau, displayed a conglomerated heap of letters, and said, ” There you are; help yourself!” It may be considered somewhat remarkable that though the Post-office duties were conducted in this rather loose style, yet, I believe, no complaint was ever made that the letters or their contents had been tampered with.

The following (Sunday) morning found me and the worthy skipper all serene, after a comfortable night’s rest, and upon going outside to have a look round before breakfasting, the beautiful and varied scenery that presented itself to view was very encouraging, and induced one to believe there was a great future before the young settlement, could the Government be induced to throw open the fertile borders of the Brisbane and its tributaries to an agricultural population. The new arrival could observe, in making an inspection of the clearing around the settlement, that a large portion of the land in and about the new township had been under cultivation, and at the time I speak the roots of the corn-stalks still remained in the holes made around them, and the few gardens and cultivated spots about the settlement were teeming with wonders of the vegetable world.

The pineapple, the banana, the citron, the lemon, orange, and apple, with mulberries, grapes, and other fruit bearing trees, were of remarkable size and beauty; and gave satisfactory evidence that with proper means and appliances the land would support and well repay the industrial efforts of a large population. As I intend, as I proceed with my gossip about the settlement, to advert more particularly to these matters, I shall for the present content myself by stating that I ever afterwards considered it rank heresy for anyone to assert that Moreton Bay was only suitable for the rearing of stock. After having breakfasted it was arranged that we should amuse ourselves by taking a stroll round the settlement and take a bird’s-eye view of the surrounding country from the top of the old Windmill. What I saw and heard in our rambles about town, I must defer narrating until a future issue.

1 Comment