From Convict Settlement to Separation

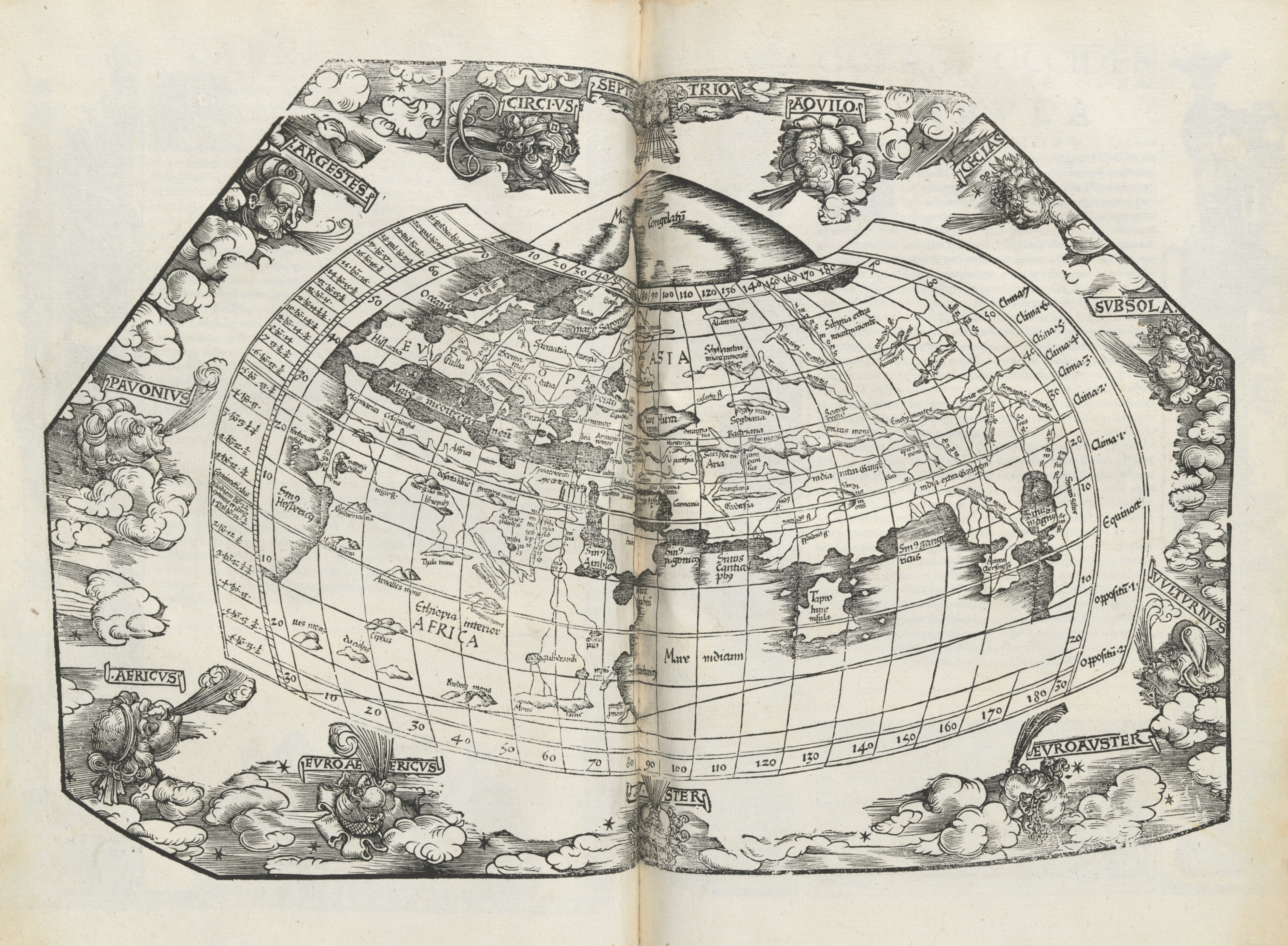

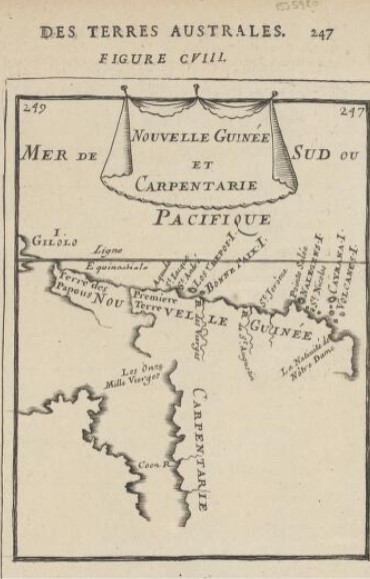

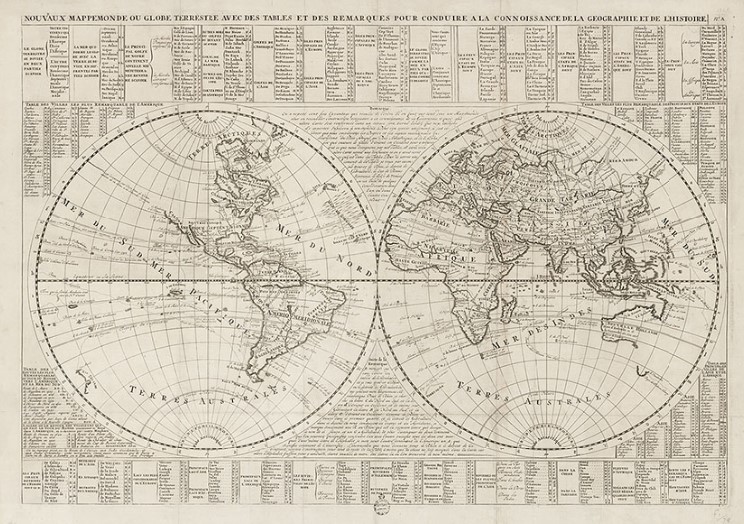

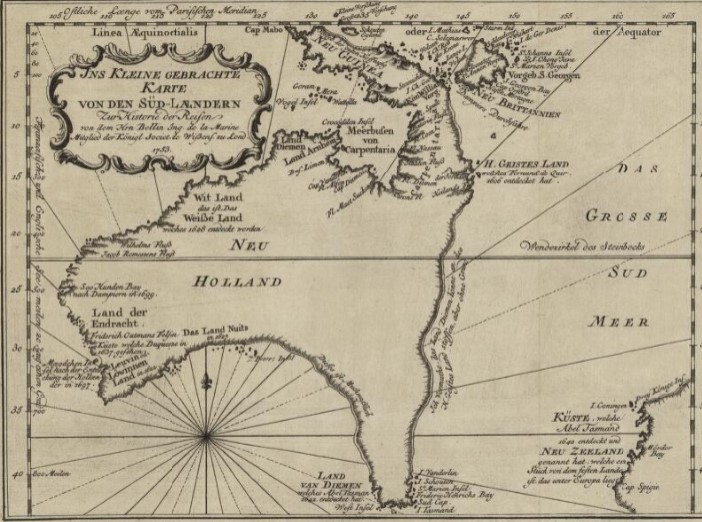

Map of the World (published 1500s, New Guinea 1600s, and globe 1720s. We’re in there somewhere.

Beyond Here Be Dragons

For centuries, New Holland existed as only a vague concept. The Dutch had been to the west and south, leaving – for reasons best known to themselves – plates nailed to things on land. They made a good survey of the western coast, and referred to the place as New Holland.

Captain Cook and Joseph Banks charted the eastern coast in 1770. Matthew Flinders was able to prove that Australia was an island continent in the years following. But what about that eastern coast? At least the upper part, halfway to Nouvelle Guinea? Once the British government had established roots in the new country (without any permission from its actual owners), it was decided to see what kind of place it was, and to what use it could be put. Enter the surveyors and explorers.

The Surveyors

1823-1824: John Oxley

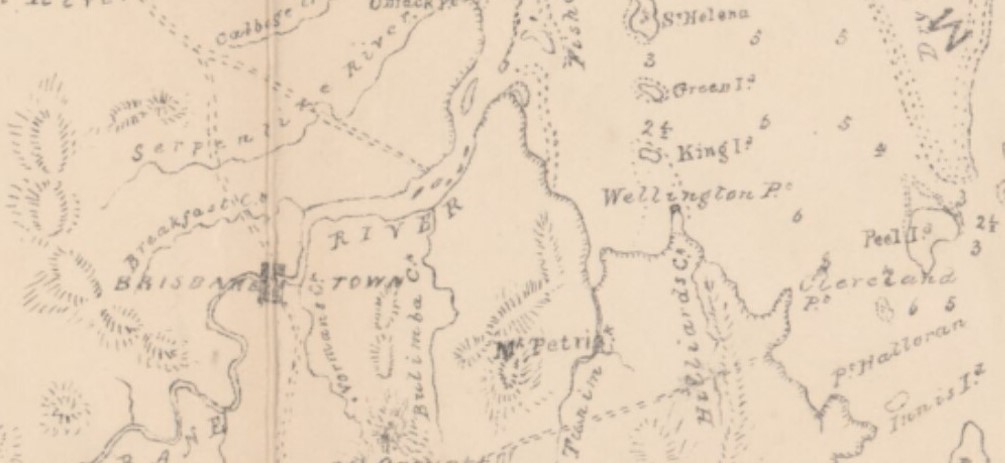

Notes from Oxley’s survey at Moreton Bay. “Fine open Country rising into Gentle Hills and Vallies. Rich Flats of Land. FINE Open Grazing COUNTRY. Rich Land and Fine Timber.”

John Joseph William Molesworth Oxley (1784-1828) was sailor, explorer and surveyor who lived a fascinating, but all too brief life. Born in Yorkshire, he joined the Navy at 14, arriving in Australia whilst still a teenager. After his naval career, he became Surveyor-General, exploring the Lachlan and Macquarie rivers (and if these names seem familiar, he was engaged to Elizabeth Macarthur in 1812).

Oxley surveyed with the botanist Allan Cunningham, another man to chart the area around Moreton Bay. In 1823 and 1824, Oxley explored the river Brisbane, coming across a place that eventually became the settlement.

His personal life was decidedly complicated. He had three daughters out of wedlock with two different women, and later married another, Emma Norton, and fathered a girl and a boy. His ventures in private enterprise in the late 1820s met with little success. He died after a long struggle with ill-health, caused, he believed, by the physical challenges of his treks through New South Wales.

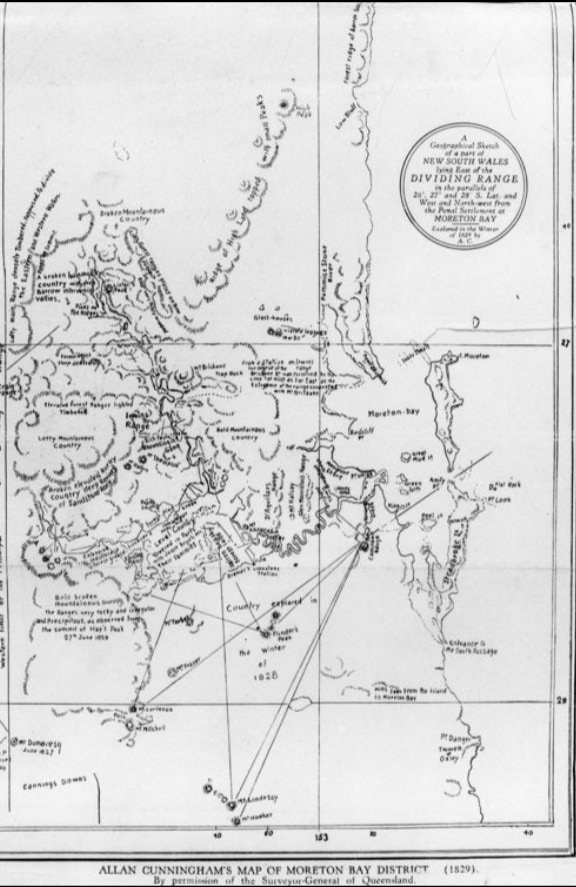

1829: Allan Cunningham’s Geographical Sketch

Allan Cunningham (1791-1839), was born in Wimbledon, apprenticed to the law, but found botany a much more rewarding career. On the advice of Sir Joseph Banks, Cunningham travelled to Australia, and explored with Phillip Parker King and John Oxley.

Cunningham’s greatest legacy has been his extraordinary botanical collections and writings as Collector for the Royal Garden at Kew. He returned to Australia in 1837 but found that his position in Sydney of Government Botanist involved growing vegetables for public servants. Understandably, the great botanist resigned in disgust. He passed away in 1839, of consumption.

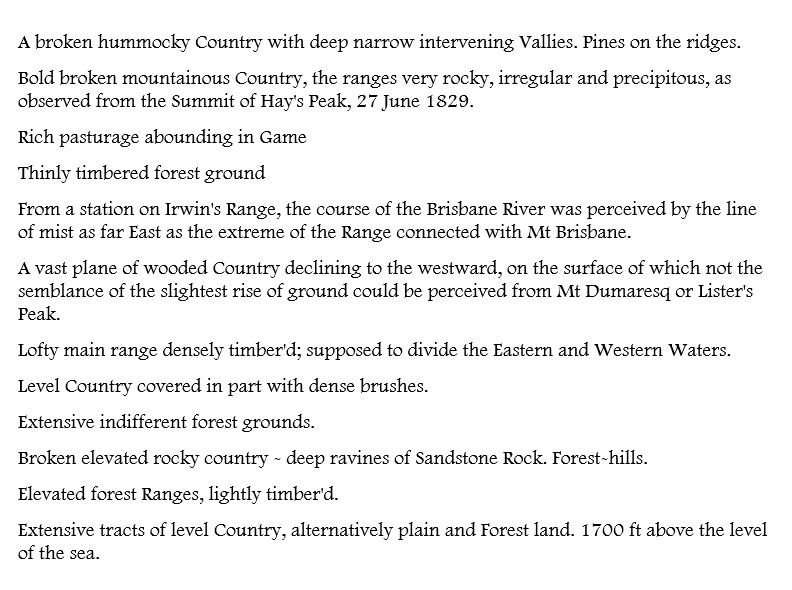

Allan Cunningham’s Geographical Sketch was not an official surveying document, rather a botanist and explorer’s fascinated account of the countryside he encountered. Very little of what he saw had been named by Europeans, and Cunningham was free to describe the country in his own terms. He took measurements, naturally, but also included in his sketch the semi-poetic description of tracing the river by a line of mist, and noticing pastural land “abounding in Game.”

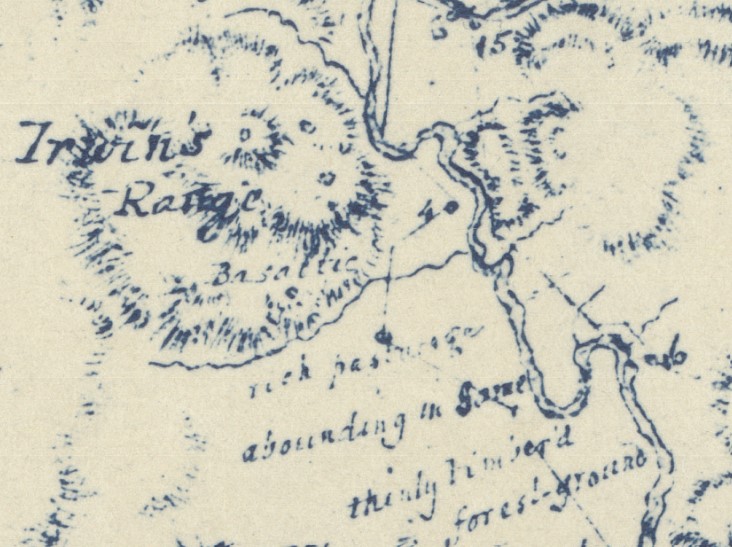

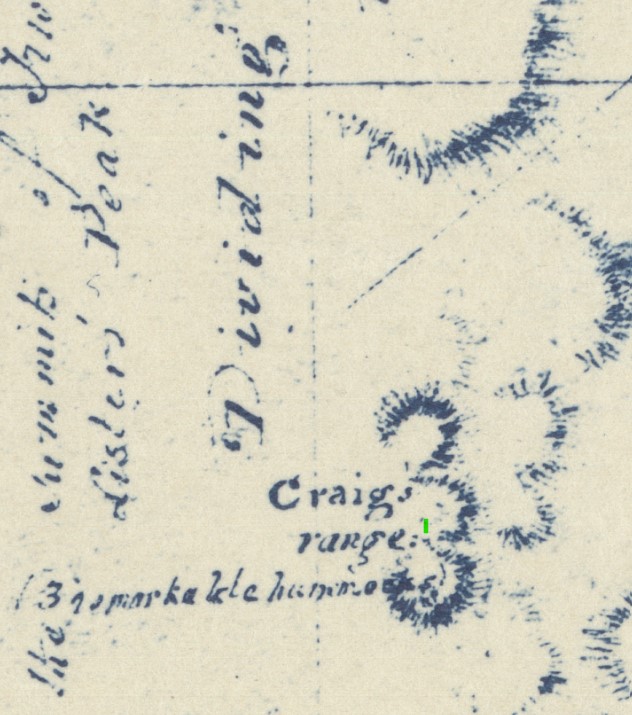

Details of Allan Cunningham’s map, together with his rapturous descriptions of the places he saw.

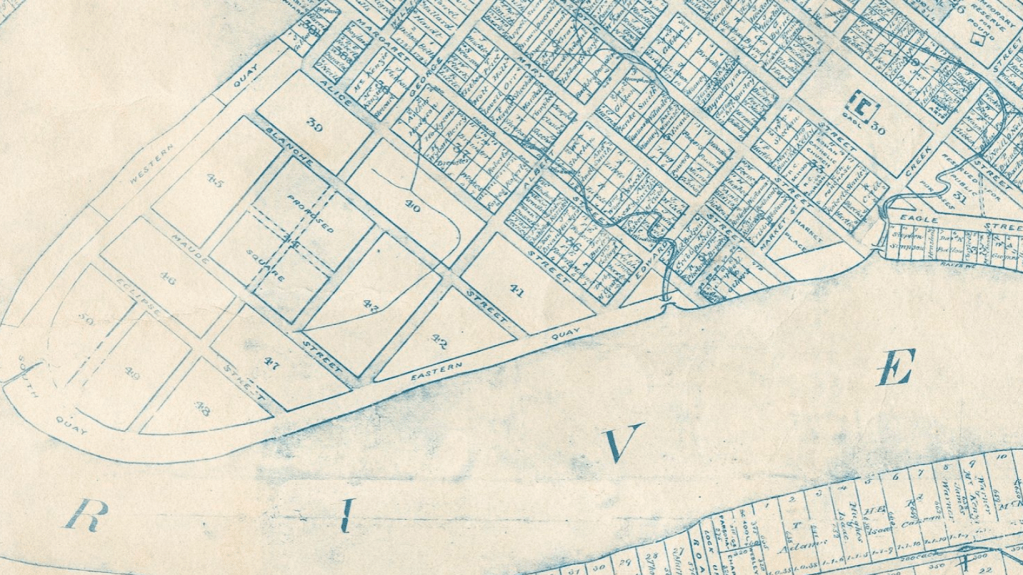

1839: Major Barney’s Plan of Brisbane Town

George Barney (1792-1862), joined the Corps of Royal Engineers at 16, and came to Australia after the Napoleonic Wars and a stint in the West Indies.

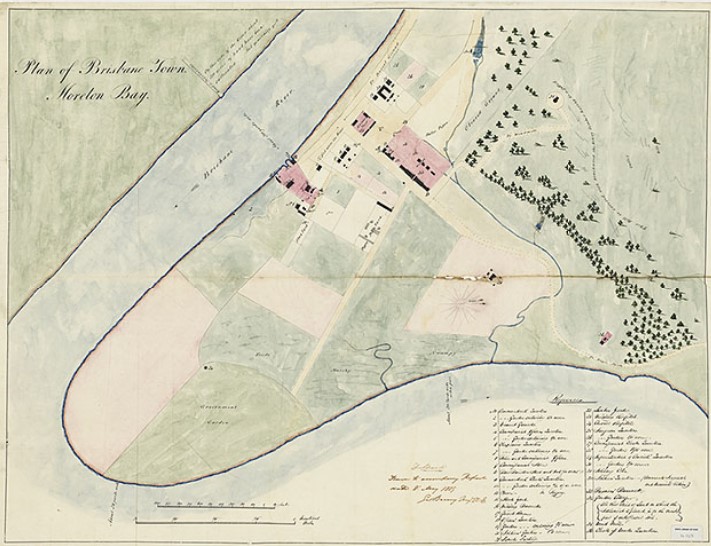

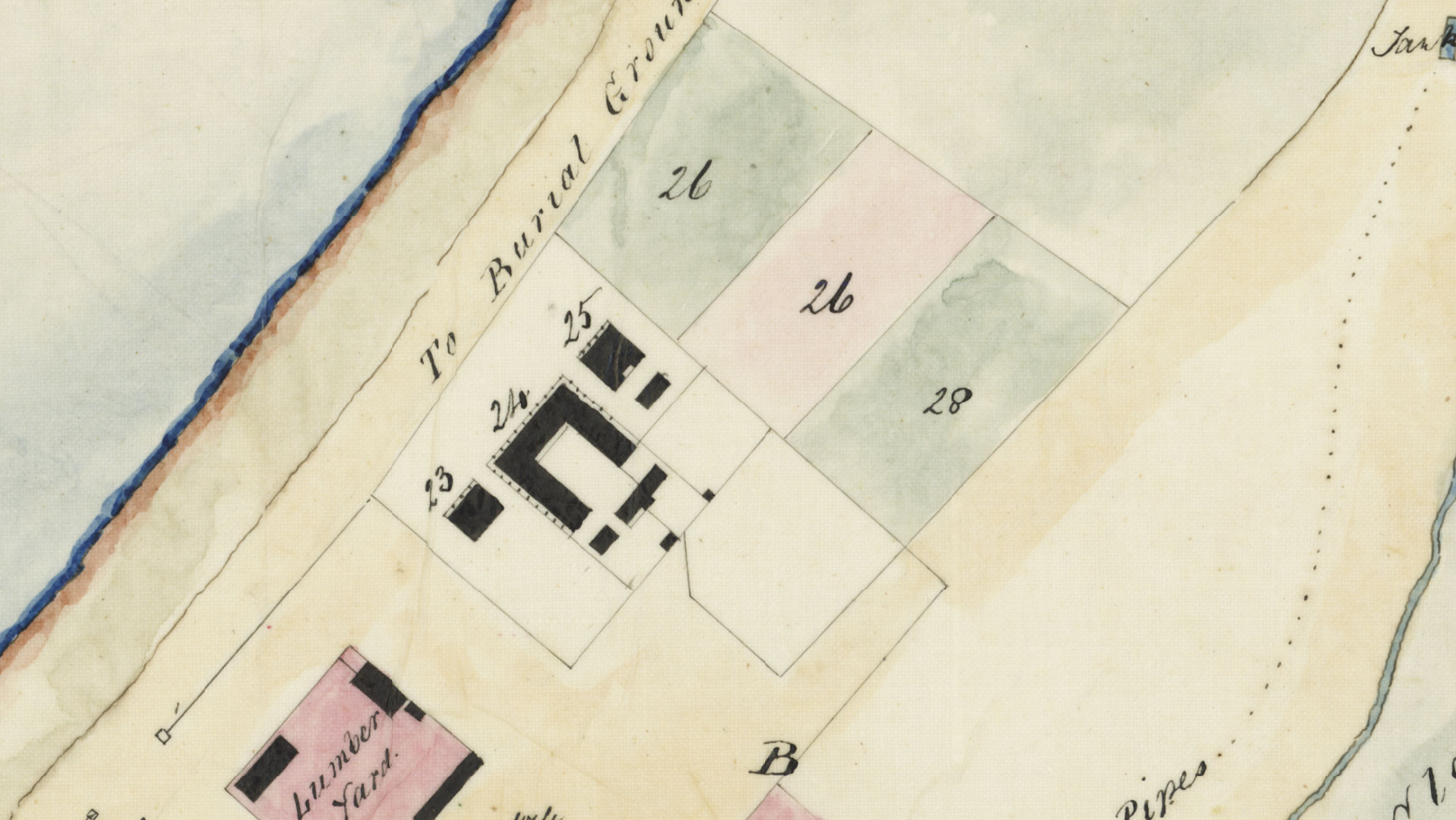

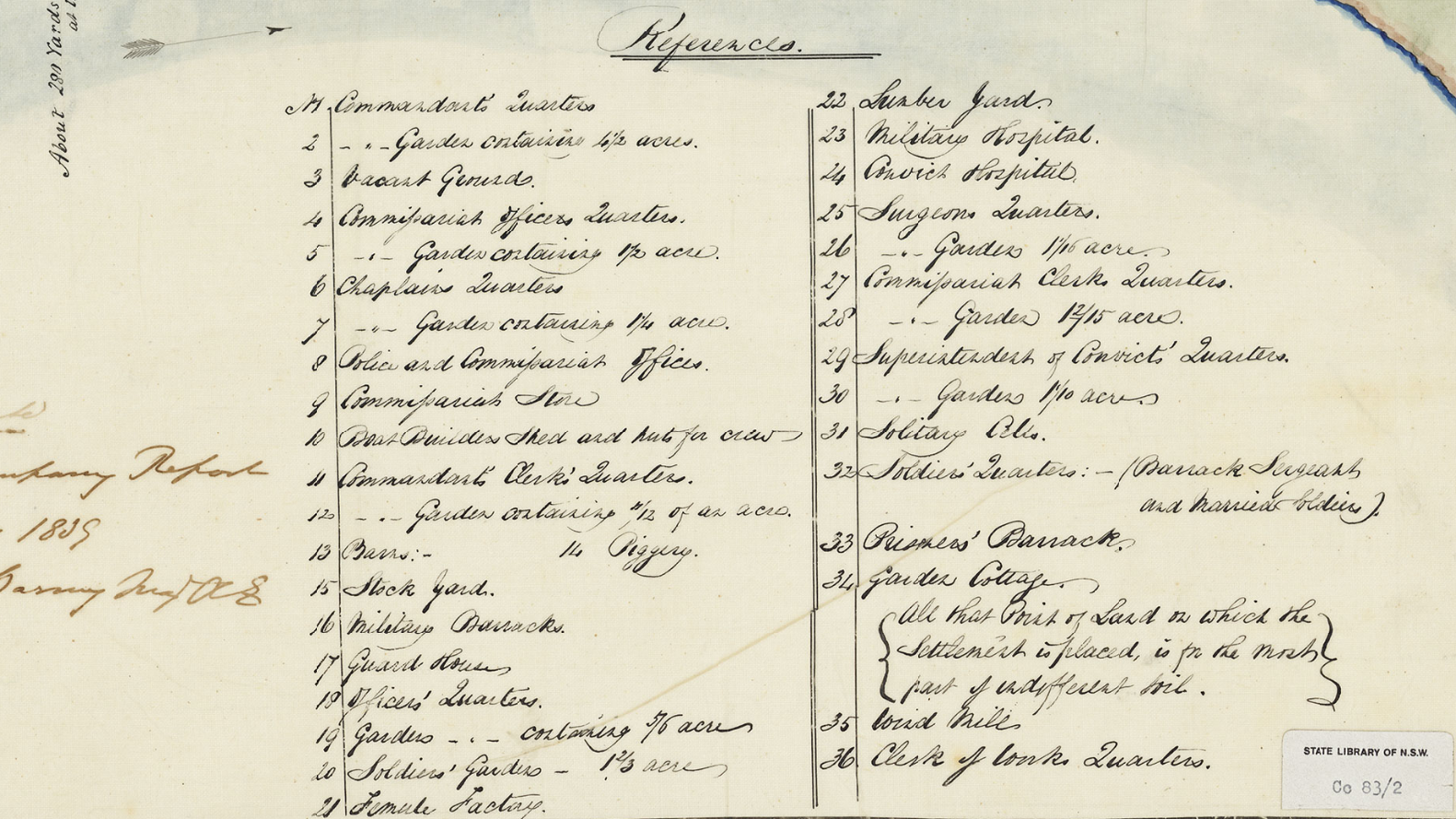

He made a plan of Brisbane in 1839, during his term as Colonial Engineer. This document shows the layout of the place, and the buildings that stood at the end of the convict settlement. There were 39 convicts left at the settlement, and no privately owned structures existed (Andrew Petrie had built a house, but it was considered to be the Clerk of Works’ dwelling until he successfully petitioned the Governor to remain there and call it his own).

Details from Barney’s map, including Gardens Point, Government Buildings and the Commissariat precincts.

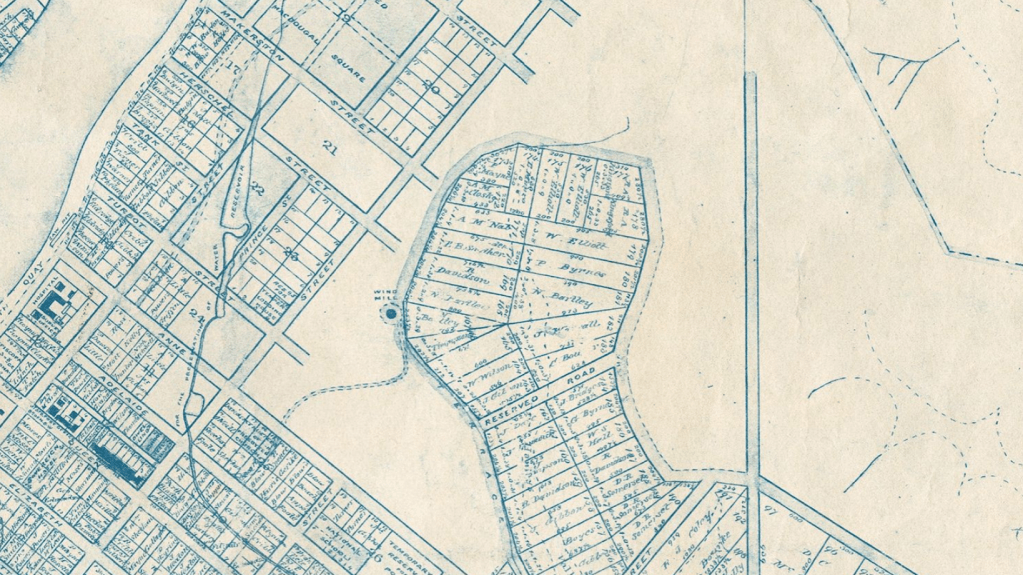

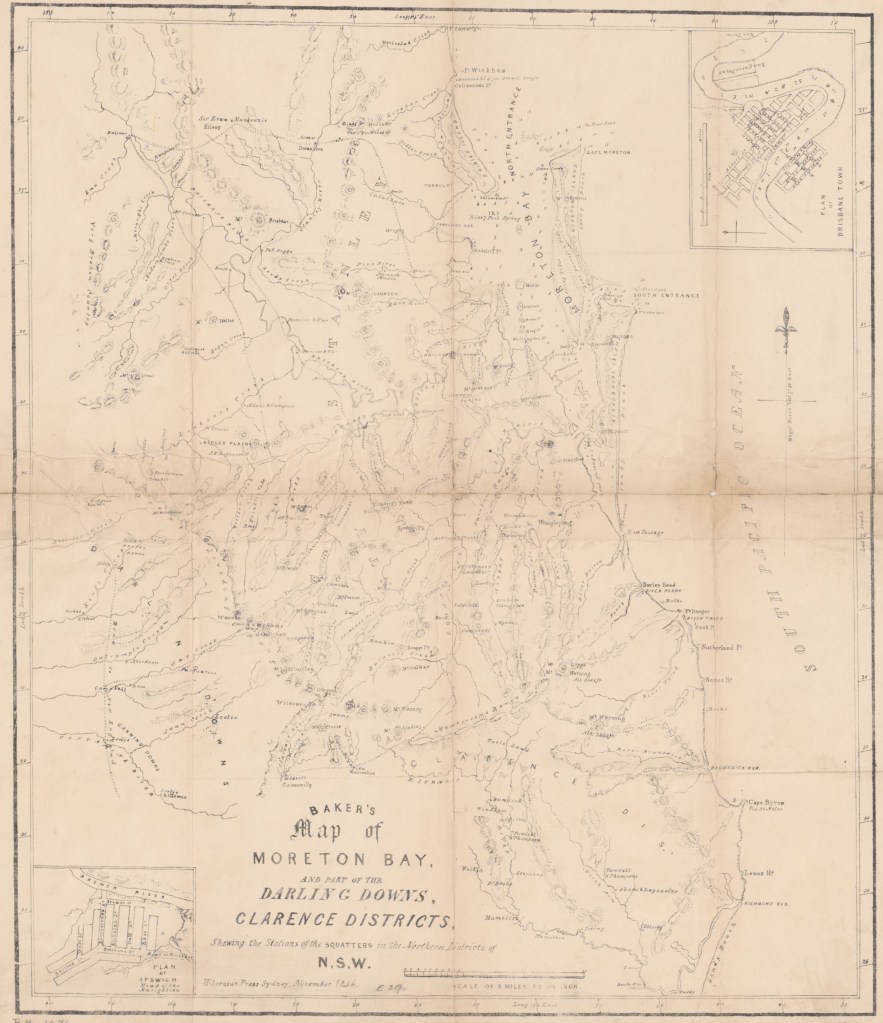

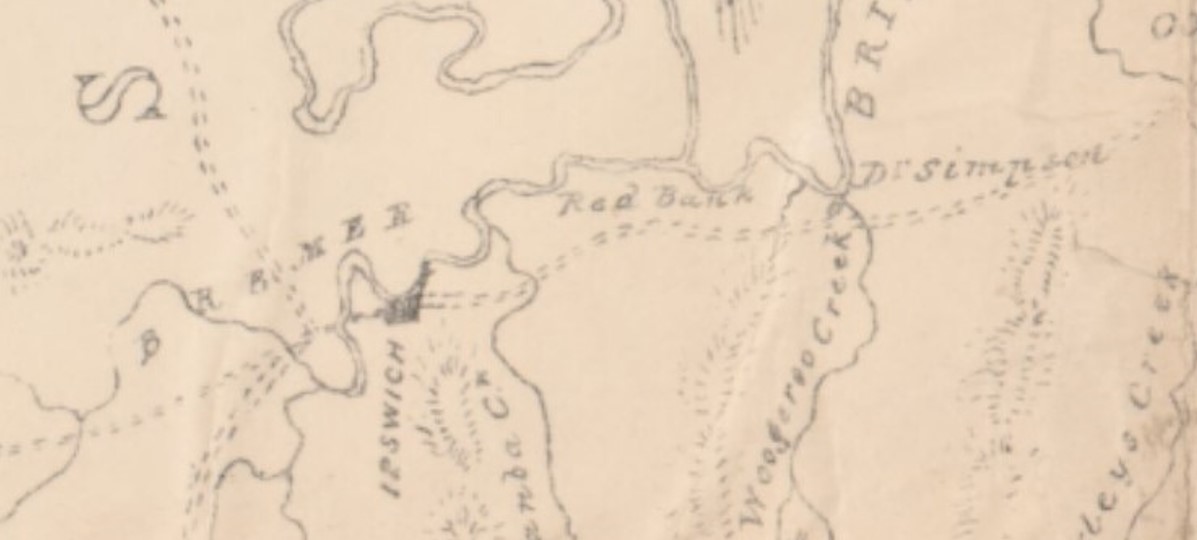

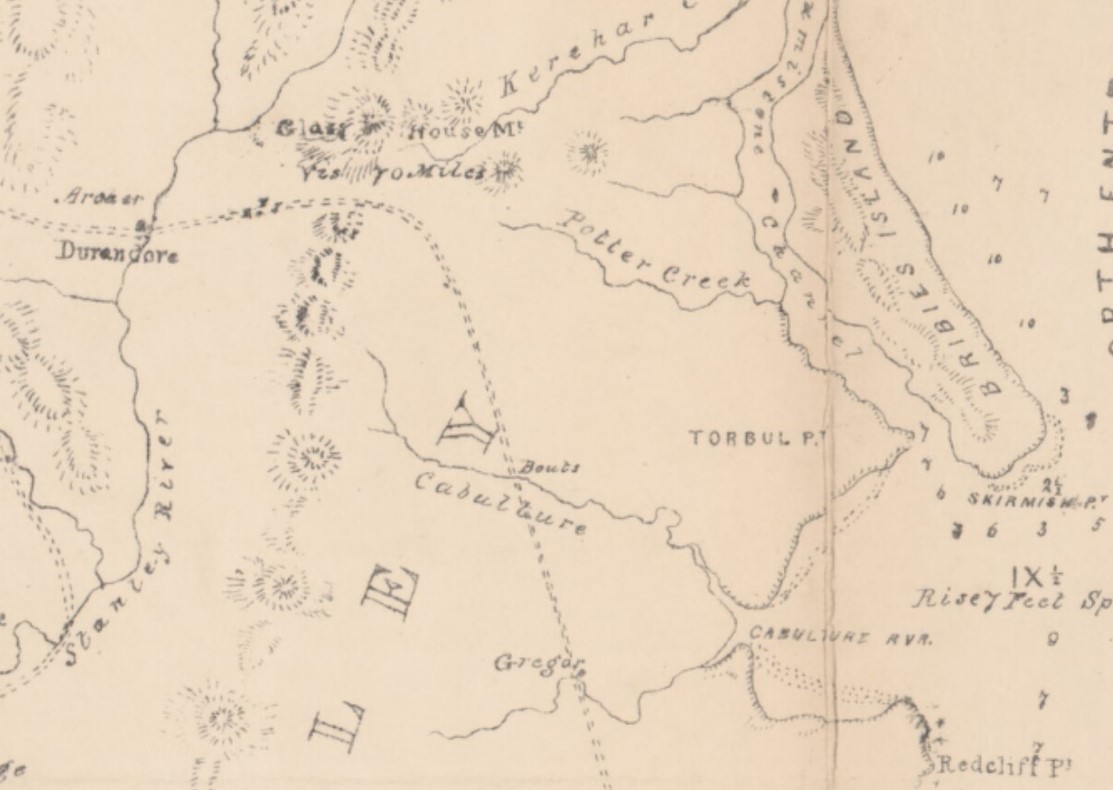

1846: Baker’s Map of Moreton Bay and Surrounds

William Kellett Baker, of the cartography firm Bakers, produced this map of Moreton Bay and surrounds, extending roughly from Point Cartwright to the Byron Bay area. He didn’t map Brisbane town, which was struggling along with fewer than 1000 inhabitants, but made a careful record of who owned (or squatted on) what piece of land. A lot had changed in seven years – the only inhabitants of the region north of the Tweed River had been in the convict settlement when Barney planned the area in 1839.

Familiar names appear on the map – Wickham, Ferriter & Uhr, Bigge, Campbell and Sir Ewan MccKenzie.

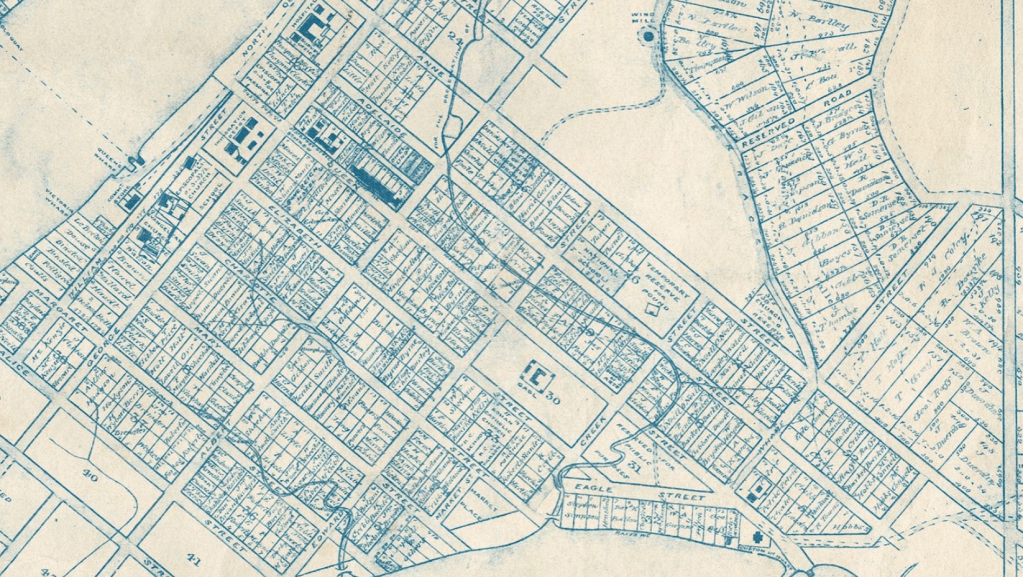

1855: Plan of Brisbane Town

Sixteen years after Major Barney made a plan of Brisbane Town with only 36 place references, including barns and a piggery, a Plan of Brisbane Town was produced. The Sovereign Hotel was listed for sale, and its appointments and features are set out at the bottom of the map. It seems that the plan was either sponsored by the hotel, or completed as part of the selling process. Although frustratingly small here, it can be enlarged on viewing at the State Library of Queensland.

It is another fascinating document, because it shows exactly who owned what and where in 1855. Another feature is the growth of South Brisbane, which extended four blocks deep. Spring Hill has begun to be populated beyond the Windmill. The site for the proposed new gaol, however, Petrie Terrace, is out in the wilderness by 1855 standards.

In Kangaroo Point, the establishment figures owned much of the property – the Petries, Henry Stuart Russell, the MacKenzies, RJ Coley and Captain Wickham. William Kent owned land there, as well as substantial holdings in South Brisbane. In town, familiar names appear – Patrick Mayne, G S Le Breton, George Edmondstone, Daniel Skyring, Stephen Simpson, Cribb and Sheehan.

The 1855 plan of Brisbane features streets that never came into existence, thankfully. They were Blanche Street, Maude Street and Eclipse Street, bounded by Western, Eastern and South Quay. The proposed streets were occupied by the remains of the Government Gardens, now the Botanical Gardens.

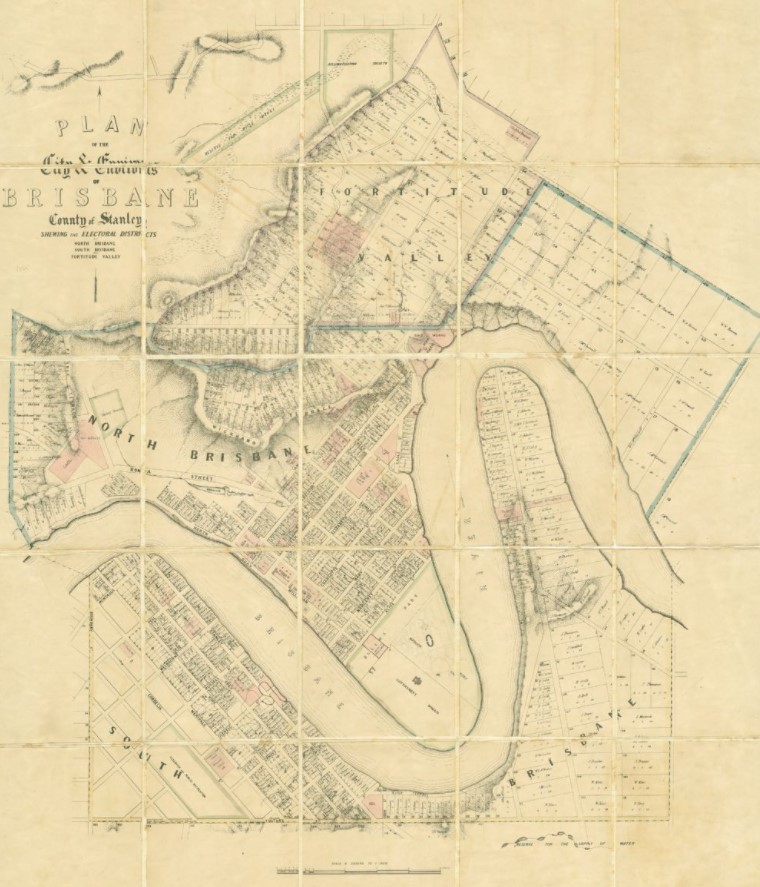

1860: A Plan of the City and Environs of Brisbane.

In 1860, just after Separation, a new map shows produced by the firm of G. Slater shows some small but important changes. The burial ground at Skew Street is gone. Blanche, Maude and Eclipse Streets have disappeared – the area they were to take up became the Botanical Gardens and Government Domain. The Gaol at Petrie Terrace is no longer in the bush – there is housing all around, a Military Barracks next door and a Cricket Ground not far away.

Fortitude Valley is expanding, although few homes have changed hands on Kangaroo Point (DK Ballow is still listed as a landowner there, some ten years after his demise).

A Police Court occupies the site of the old Gaol in Queen Street, and a large tract of land between Spring Hill and Fortitude Valley is reserved for the rifle range (the Hospital was still in George Street, meaning that the sick of Brisbane did not have their sleep disturbed by rifle shots).

All this had occurred within two decades of the Colonial Engineer drawing his 36-reference sketch of the Settlement.

Maps: National Library of Australia, New South Wales State Library, Queensland State Library.

Explorers: Australian Dictionary of Biography.