First published in the Brisbane Courier, Saturday 21 August 1869.

As I have before remarked, the settlement, as regards house accommodation, consisted entirely of the various buildings erected under the authority and inspection of the Government officials during the penal times. But it was naturally anticipated that the purchasers of the land sold at the first Government sale of town allotments would improve their properties. Several pairs of sawyers commenced falling and converting into boards and scantling the numerous pine trees then abounding in the scrub lands bordering the township, and a little cutter named the Nelson was busily employed procuring shells (to be converted into lime) from the shores of the bay.

Unfortunately for the owner of this little craft, the description of buildings erected in the early days of the settlement did not necessitate the use of a large quantity of either bricks or mortar, and the result of this shell speculation was anything but favourable to the worthy projector, and, like many subsequent schemes to open out now industries, was before the age, and necessarily unprofitable.

There is, however, many little recollections worthy of a passing remark connected with the Nelson. Who of us old hands forget the jolly good-humoured owner, little Hamilton, or the skipper of this the only colonial craft owned in the settlement, Long Tom; and when I add the name of O’Neil, what a budget of fun rises to recollection in connection with those names and the “corner”?

As very few of the present generation can have the slightest conception of the sayings and doings of the old residents in that rather remarkable corner, perhaps it may not be out of place to bring some of them prominently forward in this history of old times.

The “Corner” – the veritable corner that has so much to answer for in the dispensation of villainous drinks and questionable IOUs -comprised that portion of the old (Convict) barracks forming the corner of Queen and Albert streets, the extreme end being occupied by the great O’Neil and another, who, for prudence sake, I decline to name; but there is one name connected with old times who lived and moved and had his being thereabouts, who deserves passing mention – the pseudo philanthropist Little[i]; not Robert, recollect, but the very antithesis of our Crown Solicitor.

I won’t say Little made much money by selling bad grog or retailing questionable merchandise; but he and his partner made money, bought land, built a large (for the times) brick house, and finally, to crown his good works, built a chapel (by-the-bye, the first erected in Brisbane), and then, it is said, went off with another man’s wife, a sad Don Giovani.

The Brisbane poet of that day I fear had this “Little” humbug in his mind’s eye when he concluded the following satire, in that well-known song “The Merry Boys of Brisbane :”

Some shake at us their pious bonds,

Go home and solemn tears they shed,

Then gloriously get drunk in bed-

Merry boys of Brisbane.

However, that corner was a caution, and I venture to say, at this distance of time, that there are many old hands now remaining in our midst who could tell some queer and funny things said and done by the various men who have from time to time taken up their quarters at the “lucky corner.”

And that reminds Old Tom of one fact: Ben Cribb[ii] bought this corner, made money upon it, and although he has fooled it at another corner at the head of the navigation, yet I will venture to prophesy that the day is not far distant when the firm will havoc to come back to the lucky corner.

But Johnny Hamilton, long Tom O’Neil, and the Little Sham have passed away, and the corner, though now rather high in the world, will have to come down a few feet, and again take the attention of an admiring public-may Cribb[iii] with it.

Before, however, wo go back to the Windmill Hill to take another glance at the clearing, let me for a few moments recall another of the celebrities of the good old times, particularly as he comprised in his person the whole law of the settlement.

Gossip about old times and forget Tommy Adams – never! Talk about Bob Little, Dan Roberts, Garrick, and others learned in the law, and leave out the name of Thomas Adams, Esq[iv].

In those days of our happy simplicity, when the whole legal acumen of our settlement was concentrated in the person (or, rather, shining nob) of our friend and boon companion Tommy Adams, who ever had his digestive faculties upset, or his sleep disturbed by visions of taxed bills of costs, or his memory or pocket taxed for wrongs never contemplated? If such an one lives in our midst, I should recommend him to take Cobb’s coach and the train to Toowoomba, and spend a night with Ocock[v], at Tattersalls; and if he does not forget all but the sweet memories of the past, write me down as – a misguided man.

Everyone who has read and luxuriated in the Pickwick Papers[vi], must have reveled in the personification of Dick Swiveller, so those who have the faintest recollection of Adams, must recall to memory Tommy Adams’ factotum, Richard Stubbs[vii], that laughing, rollicksome young limb of the law, as full of mischief as a pet monkey, and as ready to negotiate a loan for himself or any other man, if the security was forthcoming, as the smartest of my uncles. The old saying of like master like man never was better verified than in this pair of Brisbane celebrities; prodigal to excess when in funds and sharing the last shilling with a friend.

If the world holds possession of the living form of old Tommy Adams, may his professional fees be as large as his heart, and when the closing scene in this world shall come to pass, I trust his faults will be buried with him, never more to be remembered by those who, knowing his good qualities in life, shall say at his death, Alas! Poor Tom!”

A few words for the old solicitor’s aide-de camp, R. B. Stubbs. It must be remembered in those days, when gentlemen learned in the law were scarce in Brisbane, that the true cause of such ever-to-be-thankful scarcity was not from the paucity of legal talent in the metropolis of the parent colony, but simply from the want of means, or rather no means at all, to fee a lawyer, that the scarcity existed.

It will, therefore, be naturally supposed that the plunder to be obtained by old Tommy Adams and his attendant was not more than sufficient to keep soul and body together, with an occasional “bust.” Nevertheless, the pair pulled well together; in fact, I can say with-regard to our Richard, that, whether in luck or sadly out at the elbows, his good temper never deserted him. One instance here recurs to memory that deserves a passing remark:

At the time of the wreck of the ill-fated steamer Sovereign, on the 11th March, 1817, Stubbs was a passenger by her, en route to Sydney; and when that vessel, by the breaking down of the engines, foundered on the dangerous bar at the southern entrance to the harbour, and out of fifty-four persons, comprising the crew and passengers, only ten reached the shores of Moreton Island alive. Dick behaved most heroically in that trying hour, using, it was said, his best exertions – being an excellent swimmer – to save the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Lyne and their little ones, both of whom, however, perished on that fatal morning. The Sovereign, at the time of the disaster, had on board ten cabin and twenty steerage passengers, and a crew of twenty-four souls. Out of this number, only three steerage passengers, two firemen, one seaman, two boys, the Captain, (Cape), and Mr. H. B. Stubbs, reached the shore alive.

The loss of this steamer and her valuable cargo was justly chargeable to the continued neglect of the Government of that day, who, for the previous six years had constantly ignored every just demand of the Brisbane people, one of which was the opening out the south passage to the bay by removing the pilot from Amity Point on Stradbroke Island to Cape Moreton on Moreton Island. The total loss of the Sovereign, with so many valuable lives, at last compelled the Government at Sydney to take those measures for the safe navigation of the harbour which should have been done years previously.

It will scarcely be believed in these latter days that for some six or eight years after these northern districts were thrown open for occupation, and numerous vessels, both steam and sailing, were arriving and departing with valuable cargoes, one old man had to perform the varied duties of harbor master, sea and river pilot, assisted by a boat’s crew of four or five men, composed of convicts and blackfellows. The harbor at the same time being without buoys to mark the dangerous shoals, and the river channel un-beaconed, except to a very limited extent. Can it, therefore, be wondered that a universal cry arose for separation throughout the most populous districts, and a determination arrived at never to cease to agitate for that boon until the desire of those at the head of the colonial affairs to keep these immense districts as one large sheep walk had been frustrated.

Thank God, after ten years unceasing effort, that great object was accomplished. But the battle of responsible government has not yet been fully realised. Still, as the colony progresses and goes ahead – it must, in spite of mismanagement and bad government, these and other grave matters will be attended to, when the colonists get the right men in the right place.

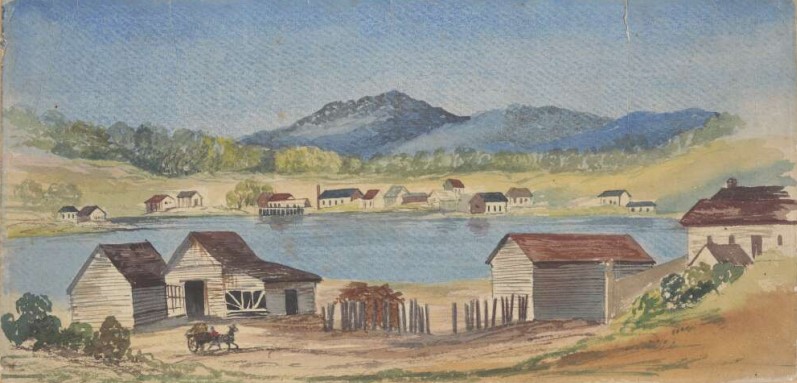

Once more we will go back to the old Windmill, and as we take a parting glance at the settlement, let us for a brief space observe a few of the leading characters who at that time occupied the very limited social circle of the premature settlement.

The first in my recollection shall be John Canning Pearce[viii], a plain, blunt-spoken, irrepressible Englishman, prone to a fault to join issues with his best friend upon the slightest provocation, yet, at the same time, overflowing with the milk of human kindness. As a storekeeper, J.C. Pearce was not successful; few, in fact, were in those days of damper and salt beef – an advantageous offer to take charge of a station below the range caused a revolution in the affairs of this well-remembered old colonist – and the vicissitudes appertaining to squatting pursuits were fully exemplified by Mr. Pearce during the many years he followed that avocation; and it is believed that, had he not, in a foolish moment, indulged in an experiment to introduce steam communication between the settlement and the head of the navigation, John Canning Pearce would not have been obliged to wear out the remnant of his days as clerk in the Brisbane gaol. Poor old fellow! Although ten years have passed away since he was placed in God’s acre, his memory and worth remains in the minds of old hands.

Next door to the store of J. C. Pearce, situated in the lower range of the old barracks, was the business-place of that old trump, William Pickering[ix] – trading under the style and title of Pickering and Loyse. It is only recently this old celebrity passed away from our midst, full of years and honoured as an upright man, and for years previously had worthily filled the office of Official Assignee.

Mr. Pickering’s early career in the settlement was not of a very bright and profitable nature, on to contrary, like many others who had embarked in trade on the opening out of the district, he felt how hard it was in a limited community to make a pile, or in fact, make tucker.

Yet the hope of good times coming led him and many others to live, or rather, vegetate through some of the best years of their lives, with the laudable endeavour to make and leave a place better than they found it; perhaps, however, in the day of old age and decrepitude to be rewarded by an ungrateful world with neglect calumny.

Taking this view of by-gone days, I do not think it would be out of place to lay before the readers of your journal some of the difficulties and disagreements which the early settlers in those districts had to encounter in their praise-worthy endeavour to found a home for their wives and little ones.

As an illustration, I will instance the hearty welcome accorded immigrants arriving in the young settlement during say the first and second years of our early history.

The coasting crafts employed in the inter-colonial trade of the colony consisted mostly of vessels of small tonnage and of an easy draught of water, suitable for bar harbors; the one or two employed between the ports of Sydney and Moreton Bay did not exceed some seventy tons burthen. It may, therefore, be imagined that the comfort of passengers on board vessels of that class was not altogether suitable for long voyages. Nevertheless, it frequently happened that, during the summer months and when sailing vessels had to contend daily for weeks together against the north-east winds, that the trip from Sydney to the bay occupied sometimes three weeks to one month, the result was that passengers in the lower walks of life landing at Brisbane felt somewhat anxious to get their heads under cover, so as to permit them and their little ones to get an overhaul and a fresh fit-out for the campaign before them.

Let me attempt to describe the state of things they found on landing for the first time at the settlement of Brisbane.

They came ashore wearied with sea sickness and the long and tedious voyage – half-starved from their provisions and water falling short owing to the protracted length of the trip, and revelling in the anticipation that, with the few shillings at their disposal, they would be enabled to get some nourishing food for their little ones.

Vain imaginings! No baker’s shop[x] with its goodly display of soft tommy greets the eye in the leading thoroughfare of the settlement; no butcher’s shop held out its tempting joints to the hungry long face; no “lodgings to let” were displayed in the windows of the few houses and public edifices that constituted the town; and when, at length, the weary feet of the newly-arrived found a resting-place, it would in all probability be under the shade of a gum-tree or in a space allotted in a dirty room in the dirty old barracks, tenanted a short time previously by doubly-convicted felons, and with every probability during his sojourn there, of witnessing the pleasurable sight of a public flagellation in the archway underneath his or their lodge-room.

On proceeding to an adjacent store for provisions, he would find some considerable difficulty in suiting his taste should it be any way fastidious after his voyage, the articles chiefly in stock at the provision depot of the settlement consisting of flour – not always of the first quality; salt beef, of the old horse tendency; tea, vulgarly called posts and rails; sugar of the blackest of the brown quality; milk, eggs, or butter not comestible at any price, the settlement not having sufficiently advanced to presume in the production of such luxuries, except amongst a favoured few whose length of purse enabled them to occupy (under rental) some of the late civil servants’ residences.

Well I remember my search about, the settlement, upon being joined by my wife and children, to obtain a place in which we would be sheltered from the night dews. And the comments – not loud, but deep – which disappointment wrung from me on finding my application to occupy, for a short time, a portion of an old boatshed near the old wharf was refused, necessitating our camping out on the south side exposed to the ribaldry and drunken orgies of dissolute bullock drivers, who, in those days, made that favoured locality their chief camping grounds.

[i] Confusingly, there were two Robert Littles in Old Brisbane. One left Brisbane in December 1846, having been in business at The Corner. This is the “pseudo philanthropist” of Old Tom’s tale. The other was a solicitor who arrived in Brisbane at the time the other left. The second Robert Little became the Crown Solicitor of the Colony of Queensland.

[ii] Benjamin Cribb (1807-1874) was the brother of Robert and was also a businessman and politician. He went into partnership with John Foote to form the major department store that bore their names. He served in the New South Wales and Queensland Legislative Assemblies.

[iii] This is probably a reference to Benjamin, but there was another Cribb – his brother Robert. Robert Cribb (1805-1893) was an immigrant by the Fortitude, who settled in what would become Auchenflower. After operating a bakery, he made numerous purchases of land. He became a member of the NSW Legislative Assembly and Queensland Legislative Assembly.

[iv] Thomas Adams was an early solicitor at Brisbane. He left in 1849 after his involvement (as a solicitor) in some litigation in Sydney. The parties took their dispute to the Classifieds of the Moreton Bay Courier, and in the process, Thomas Adams’ reputation was badly slighted by one of the litigants. Adams left the district soon after.

[v] John Ocock, Esq, was a solicitor who practiced in Brisbane, Ipswich and later Toowoomba. He was noted for his extensive practice, love of gardening, and his withdrawal from society in his later years.

[vi] Old Tom’s literary recollections are a touch misdirected – the character of Dick Swiveller appears in “The Old Curiosity Shop.”

[vii] Richard Stubbs emerged from the sinking of the Sovereign a hero but had a professional falling-out with Adams in 1848.

[viii] John Canning Pearce, in his station management days, had quite a dispute with a Magistrate, and it led to a sensational libel case. His subsequent business failures and working at the gaol made some enemies very happy. Pearce passed away in 1859.

[ix] William Pickering was a merchant, and another early settler. Pickering’s early business shortcomings we attributed, after his death, to an unwillingness to deal in IOUs. Old Tom thinks differently of Pickering, particularly in the light of the respect Pickering’s role as Official Assignee brought him. An official assignee is a court official who is made responsible for dealing with the disposal of a bankrupt’s assets, paying their debts and ensuring that the bankrupt does not engage in actions contrary to the bankruptcy laws.

[x] Henry Savary (the French baker) had yet to open his premises, shown on the 1844 Gerler map.

1 Comment