In early September 1889, wealthy publican and landowner William Goodwin Geddes discovered that his son, who had disappeared (presumed drowned) at Toorbul near Caboolture in 1877, was still alive. That was the good news. The bad news was that his son resided in a Lunatic Asylum in Adelaide. The worse news was that the AMP Society would like its life insurance money back, with interest, please and thank you.

The “Geddes Mystery,” as it became known, was irresistible to investigative journalists, who felt that something was amiss with the story as it had been told thus far. For two months, every publication in Queensland and South Australia presented analyses, points of view and carefully-worded speculation.

For the family, the Geddes Mystery brought up decades-old grief and pain, and surrounded them with scandal. That is, until a mystery witness came forward.

A head injury and a drowning

William Goodwin Geddes junior was born in 1856 in Charlotte Street, North Brisbane. The family relocated to Caboolture, and had another son, Henry Raymond, there in 1857. William Senior built a successful business over the years, and was able to provide excellent educations for his children. William Junior excelled at Brisbane Grammar school, became an excellent swimmer, and embarked upon a promising career as a surveyor. He was one of those golden young men who succeed early and make a tremendous impression on everyone they meet.

Young Goodwin Geddes’ career as a surveyor took him to distant parts of Queensland, and prior to his disappearance on 29 October 1877, he had a serious accident at Pikedale in the Southern Darling Downs. It seems to have been a fall from a horse, in which Goodwin sustained a bad head injury. He was recuperating at a beach house his father had bought near Caboolture, having been quite ill for some time. Goodwin and his brother Henry went for a swim in King John’s Creek, a tributary of the Caboolture River, when Goodwin disappeared and Henry could not find him. The family, locals and the police made a lengthy search, to no avail.

William Goodwin Geddes junior had made out a will, and taken out life insurance policies to the value of £2500, to be paid to his mother. The insurer was the Australian Mutual Provident Society (AMP). The company had some misgivings about paying it out when no body had been recovered, but the Geddes family were respectable people, and the claim was successful.

Life for the Geddes family was sadder, but they continued with their activities – which seemed to involve a lot of good works and even more horse racing.

The life of Louis Brennan

In 1883, a man named Louis Brennan, or Lewis Vincent Breenon, worked for the Survey Department in Western Australia. He went on 10 days’ leave, and did not return. On 14 March 1884, Breenon was found loitering near the Bank of New South Wales with a loaded revolver in his pocket and a mask on his face. Mr Breenon was not skilled at covert loitering, having elected to wear a smashing pair of blindingly white trousers to his stakeout. He was spotted and arrested before he could do anything too foolish.

At his Court hearing, Breenon’s lawyer told a tale of a talented young surveyor, who had testimonials from prominent surveyors in New South Wales, South Australia and New Zealand; and who had suffered a sun-stroke that affected his mental and physical health so badly that he was unable to work or pay his bills. He had been drinking heavily, and hiding out in the bush. In desperation, he took a revolver from the Survey Office (from which he had not been officially dismissed), and, in a “low, nervous and depressed state of mind,” found himself in the vicinity of the bank with his white trousers and a borrowed gun. He didn’t commit any robbery. Would putting him in gaol be the best solution asked his lawyer? The Magistrate thought so, and gave him six months. Poor Breenon fainted dead away.

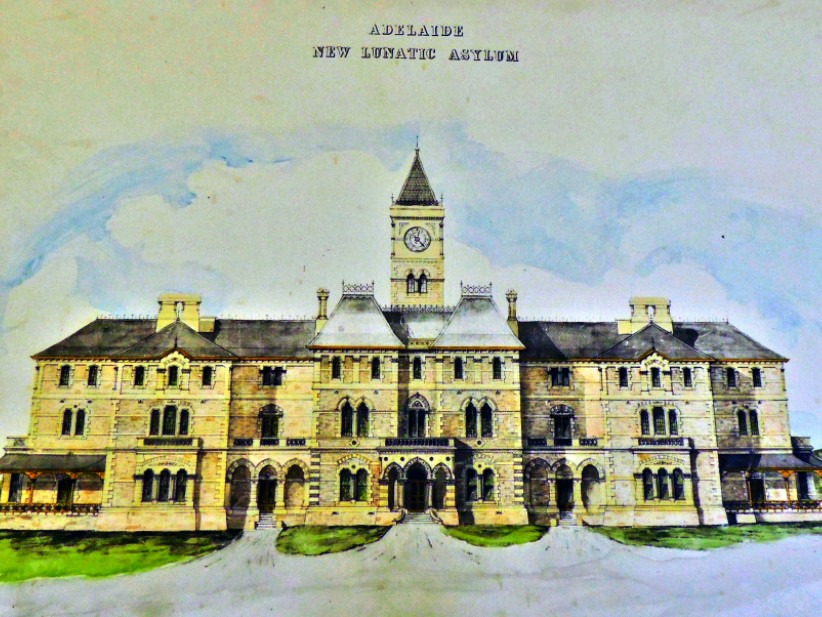

After serving his sentence, Lewis Vincent Breenon met and married a young lady named Alice Maude Rewell. They had two children, William and Edith. They moved to South Australia, where Louis (as he now was), was a loving husband and father until a sudden attack of insanity (as any mental illness was called at that time) caused him to be committed to the Lunatic Asylum as a pauper lunatic.

Poor Alice Brennan confided to the Asylum management that she was destitute without her husband, but that he had some relatives in Brisbane who were apparently well-off. Adelaide Police started enquiries with their Brisbane counterparts, and, prompted by Louis mentioning that he had once lived in Caboolture, they began to wonder if the shambolic Mr Brennan might be the long-lost Mr Geddes. The AMP society began to wonder too.

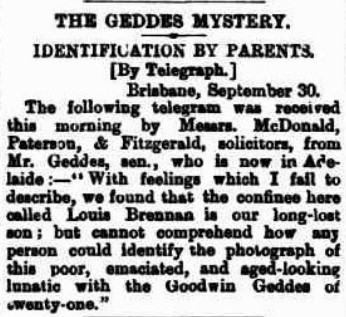

William Goodwin Geddes senior, having been shown a photograph of Louis Brennan, and not believing or wanting to believe that the gaunt, much older man in the photograph was his long-dead son, forwarded a photograph of William Junior in his prime to the Brisbane Telegraph. Armed with the Geddes photograph, the Telegraph reporter made rather a nuisance of himself to a firm of lawyers by demanding to see their Louis Brennan photograph in order to make a comparison. He was told to forward the photograph, and someone would get back to him in due course, a suggestion he did not take kindly.

John Goodwin Geddes identified

As the Brisbane and Adelaide newspapers became obsessed with the Geddes Mystery, Sergeant Atkinson – who had led the Geddes search – was sent to Adelaide to meet Mr Brennan. The policeman recognised Mr Brennan as Mr Geddes, and the inmate recognised Sergeant Atkinson.

No doubt with great trepidation, William Geddes senior travelled to Adelaide to see the man Brennan.

The press, having seized on the insurance policy and the will, were demanding Answers. Did Mr Geddes, his wife Susanna, and his son Henry Know Something? Could it have been a family embezzlement scheme? Would they pay the money back? Inquiring minds wanted to know. When journalists discovered that Henry Geddes had been admitted to Woogaroo Asylum very recently, his admission was viewed with great skepticism. Had he been put there to shut him up? Inquiring minds were getting very suspicious.

By the Sydney Bulletin we see that a gentleman lately Woogarooed will be an unwilling witness in the case, when some very racy reasons as to the cause of his sudden lunacy are likely to come out.

Warwick Examiner and Times, 20 November 1889.

As it turned out, the Geddes family paid the insurance money back immediately. They could afford to. After being pressed by AMP on the question of interest, they entered into a confidential settlement for £4900. The fact that the terms of the settlement were confidential, which is completely normal in Civil actions, caused the Brisbane Courier to lament that the secrecy would accrue more suspicion on the Geddes family. Surely a hearing in open Court would have exculpated them properly?

The Courier’s probing led to a quite explosive Letter to the Editor from WA Coudery, Geddes’ brother-in-law. In defending the Geddes family, which he did in robust terms, he dropped a bombshell of his own:

“I was astonished the other day by Mr. E. Barnes, of Gympie, telling me that when he was telegraph-master at Harrisville, at the time of the disappearance, Goodwin Geddes came to him. The poor fellow stated he wanted to get away from his family, that he had pretended to be drowned, that he had taken a good long dive, came up in the mangroves, and then climbed a tree, where he stayed until 11 o’clock at night, watching his brother and others searching for his body. His manner was so strange and excited that Mr. Barnes was told by persons who saw him that he was evidently “off his head,” and they would not have liked to sleep in the same room with him. He persuaded Mr. Barnes to say nothing of having seen him, and that gentleman knowing nothing of the insurance unfortunately gave a reluctant promise. The difficulty therefore, as you put it, of deciding peremptorily against the hypothesis of fraud on the part of the parents is removed by the undoubted testimony as to the mental state of the son, and his expressed desire that his parents should think him dead.“

After some jubilant headlines, including “Barnes knew all about it,” the Geddes Mystery had run its course. The family went back to their lives, and nothing more remained to be said.

William Goodwin Geddes junior died in Adelaide on 22 October 1894, aged only 38. His death was not publicised, and it was only when Geddes senior died in 1905, his will was published, revealing that Henry was his only surviving son. Alice Geddes, William’s widow, lived to 91, dying in 1954.

Presumably, William Goodwin Geddes – the medal-winning student and distinguished young surveyor – suffered an acquired brain injury in that catastrophic fall from his horse at Pikedale. His behaviour changed, and he entered into foolish ventures – faking his death, hanging around a bank with a loaded gun – without any thought for consequences. His family, who were remarkably well-off, did not need to diddle the insurance company, and it’s understandable that his brother Henry underwent a period of mental ill-health on finding his dead brother alive after a dozen years. Mental health treatment and diagnostics have mercifully improved out of all recognition in the last 130 years. Perhaps the Geddes Mystery might have had a better outcome if it happened today.