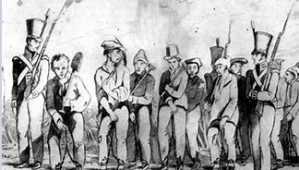

soldiers and the indigenous people

In October 1824, the New South Wales Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane and Chief Justice Sir Francis Forbes sailed from Sydney to Moreton Bay. The object of their journey was to assess the suitability of the Moreton Bay Penal Colony, which had just been set up at Redcliffe Point.

The Sydney Gazette’s brief mention of the expedition gives a remarkable historical background to that journey.

His EXCELLENCY the GOVERNOR in CHIEF, accompanied by His HONOUR the CHIEF JUSTICE, we are credibly informed, intends proceeding on a Tour of Inspection, in the course of the ensuing week, to the New Settlement at Moreton Bay. The Amity is said to convey His EXCELLENCY and SUITE. Our Gracious MONARCH was in the enjoyment of excellent health when the Mangles sailed. Louis the XVIIIth’s dissolution was hourly expected. Lord Byron, it appears, is dead.

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 28 October, 1824.

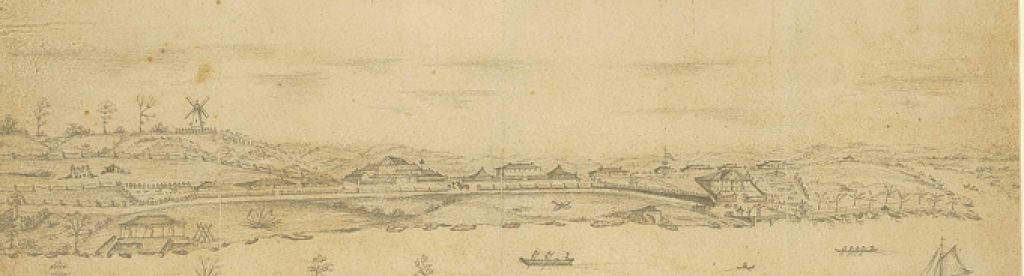

The result of the inspection was the decision to move the Moreton Bay settlement from Redcliffe to a spot further up the newly-charted river. Sir Thomas Brisbane was romantically inclined to called the new site “Edenglassie.” His Excellency did not get his wish – the future township was unromantically named Brisbane. Sir Francis Forbes must have also liked the name Edenglassie, appropriating it for his country seat some years later.

The scenery on each side was truly picturesque; on one side high open forest land would present itself, whilst on the other, a comparatively low country, covered with close vegetation, was to be seen; these views were alternate, and from the striking contrast, were of the most engaging description.

Australian, Thursday 9 December 1824

The Early Years of Moreton Bay Settlement

The removal from Redcliffe has been attributed to, variously, sandfly infestations, lack of fresh water, and hostility from the local indigenous people. The Australian hints at the reason:

“As the natives were particularly troublesome to the New Settlement at Red Cliff Point, by purloining the tools and other useful articles, at every opportunity the Commandant has been constrained to keep them at a respectful distance (from His Excellency), owing to which very few were to be seen by the Party.”

What took place at Redcliffe Point between the soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Henry Miller and the Ningi-Ningi people – possibly an armed over-response to “purloining the tools” – has not been recorded in any detail. There had been brief, violent skirmishes with white explorers in the past, but this was the first time Europeans were clearly moving in rather than passing through. Thus began the indigenous experience with armed soldiers in Queensland.

After the removal to Brisbane, the Commandant and his soldiers were careful to try and establish good, or at least peaceful, relations with the Brisbane aborigines. Bishop, and later Logan, wrote to their masters in glowing terms of their good relationship with “the natives,” who were adept at bringing back runaways, and were fond of the tomahawks and blankets they received in return.

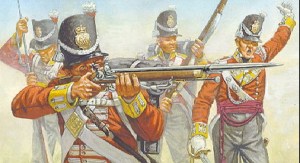

In May 1827, the peaceful settlement experienced the first “depredations” at the hands of the indigenous people. A carefully-guarded maize crop had been raided. Soldiers of the 57th had fired on two men – one was killed. It was reported to the Colonial Secretary and in the Sydney papers as an “affray with the natives,” and the soldiers were absolved of any blame.

The following January, two convicts were killed and another injured in a separate maize-field conflict. This time, the dead men had names that could be reported to the Colonial Secretary, and an indigenous man was apprehended and lodged in the cells.

The indigenous man was Bhinge Multo, who, after months in a cell at Brisbane, then a sea trip to Sydney, then more time in a cell, was found to be unable to be tried before a jury of his peers. He was eventually allowed to go free, far from his country and language. The dead men were Samuel Myers and Michael Malone, who were killed after trying to abscond from the scene of the conflict.

Meanwhile, Governor Darling was counselling Captain Logan against harsh measures of reprisal against the local tribes, and might he not consider moving the maize crop from the southern bank of the river to a place closer to the settlement? That suggestion didn’t sit too well with Captain Logan, who noted rather peevishly that the maize crops on the northern bank were now under attack.

Crop raids continued sporadically, but the main cause of discontent between the local indigenous people was cited by Logan and his successor Clunie was ill-treatment by Europeans. By ill-treatment, they meant violence against the men, and sexual violence against the women and girls. Several Europeans (including Logan) were murdered in 1830-1831, resulting in military action.

Military Raids on the Bay Islands

A soldier of the 57th regiment lately met his death at Moreton Day, by some of the native blacks, who, after decoying him from his hut, butchered the man in cold blood, and then severing head, arms, and legs from the lifeless trunk, plucked out the eyes.

Australian, Friday 2 April 1830

Outrages on both sides occurred, and on 1 July 1831, Commandant Clunie led his troops in a raid on Moreton Island, killing around 20 of the Ngugi. A warning of further retaliatory action was given, should the violence in the Bay islands continue.

Unfortunately, the violence only escalated. Convicts William Reardon, Charles Holdsworth and James O’Regan were killed by the indigenous people at Dunwich. Two soldiers, Corporal Robert Cain and Private William Wright, were injured. The murders were claimed to be in retaliation for Reardon’s brutal murder of an elder. Another raid by the 17th Regiment occurred after that, and six Nunukal lost their lives.

After the violence and reprisals of the early 1830s, an uneasy calm fell on the settlement. By 1836, Captain Foster Fyans reported happily to the Colonial Secretary that he was returning to the system of rewarding aborigines who brought in convict absconders, and felt that it was successful. The following year, Major Cotton suggested to the Colonial Secretary that bringing people from the various tribes in to Brisbane, treating them well, and letting them go home with gifts might be the solution. I don’t think that Major Cotton ever thought that this might be confused with kidnapping by the beneficiaries of his idea, which happily doesn’t seem to have come to fruition.

Free Settlement

As the convicts gradually returned to Sydney, no doubt to the relief of the indigenous women of Moreton Bay, the soldiers remained, and other settlers were coming in. One group comprised earnest German missionaries, who found a shocking state of affairs going on with the soldiers and the local tribal women.

“Saturday, 6. Mr. Rode having been in search of the Native’s Camp last week, to find a guide for Mr. Tillman to Toorbal, he was grieved to find three soldiers there for no good object. He spoke to them earnestly on the wickedness of their conduct, and though they were at first insolent, be seems to have found access to their hearts. Notwithstanding this, we thought it our duty to report this occurrence, that the commandant may devise measures to keep the soldiers at the settlement, as they have no business whatever in the bush, and as regulations exist to prevent their going farther than one mile from the settlement. Mr. E. went, therefore, on Saturday, 6th, to Brisbane Town, and on reporting what had occurred, he obtained a promise from the commandant, that a stop shall be put to their going out.” The Colonial Observer, Thursday 13 January, 1842.

The Commandant then in residence was none other than Lieutenant Owen Gorman, who was in the process of receiving a long-distance dressing-down from His Excellency The Governor for his “unguarded” treatment of female convicts and aboriginal women. I imagine that he did his best to look earnest as he gave the promise to keep his men away from going among the indigenous women “for no good object.”

York’s Hollow

In 1849, soldiers stationed at Brisbane were involved in a shooting at the indigenous camp at York’s Hollow. A rumour had been spread about the settlement that black youths had speared, or driven away, some of John Petrie’s cattle.

Lieutenant George Cameron, commanding a detachment of the 11th Regiment at Brisbane, was fishing on the evening of 28 November 1849, when advised that the aborigines were spearing cattle at Kangaroo Point.

Lt. Cameron went to the barracks, and organised a party of his men. They marched down Queen Street towards Mr Petrie’s house, intending to go on to Kangaroo Point. At Petrie’s house, they were told that John Petrie had gone to York’s Hollow to see what was happening with the local aborigines. The settlement was in a state of uproar, with rumours that an indigenous attack was imminent. The troops had already marched out, and the police, who were not armed beyond nightsticks, were barely involved.

Arriving at York’s Hollow, he separated the men into two flanks, and ordered the men not to fire without the word of command. At the approach of the soldiers, the dogs at the camp began barking, and the inhabitants began to flee. Lt. Cameron heard three or four shots fired from the left flank, and moved towards the soldiers calling them to cease fire. Another shot came from the right flank. He marched the soldiers back to barracks, where a confused preliminary investigation began. Some men seemed to be missing some ammunition, but no-one, initially, would say that they had fired. When Captain Wickham, the Police Magistrate, held an enquiry, Lt. Cameron was not willing to answer particular questions until he received orders from his Colonel.

Small wonder that His Excellency found the initial investigation to be rather lacking. The Attorney-General demanded a further enquiry, and that resulted in charges of shooting with intent to cause grievous bodily harm against three privates, William Cairns, William Bambrick and James Regennick. Cairns, the one soldier who admitted to firing his weapon, was the only one convicted, and received six months’ imprisonment. Their case was the final trial at the opening of the Moreton Bay Supreme Court in 1850.

No-one else involved was charged or court-martialed over York’s Hollow, although Brisbane’s Chief Constable was relieved of his position because he had not gone out with his constables to restore order. Samuel Sneyd was appointed to the job of Chief Constable, and set about establishing boundaries of civilian control.

Underlining the rule that the military were to have no part in policing, the Colonial Secretary that year admonished Captain Wickham for sending troops into Ipswich when there were not enough police in town. There would be no more organised military operations against the indigenous people of Moreton Bay.

.

1 Comment