Notable Brisbane Pioneers

Old Brisbane throws up some unusual characters, not least the distinguished Thomas Symes Warry. In his relatively short life, he was a prize-winning chemist, a Member of the Legislative Assembly, Magistrate and, briefly, the centre of a peculiar scandal involving the possession of a severed head.

Thomas S Warry was born in 1821 in Somerset, England, and established a career as a chemist prior to emigrating to the Colonies in the early 1850s with his family. The name Warry is an important one in Brisbane. His brother Richard was Mayor of Brisbane, and Warry Street in Spring Hill, between Water Street and St Paul’s Terrace, was named after the family.

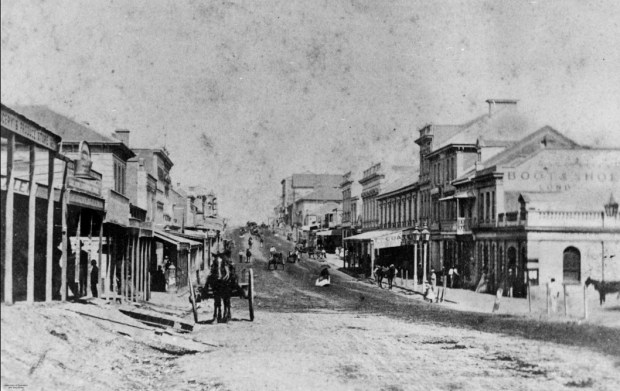

In 1854, Thomas Warry took over “the OLD ESTABLISHED business of the late MR G. F. POOLE” in Queen Street, between Albert and George Streets.[i] Brisbane Town was quite new, and old established business at that time would have been around eight years (Mr Poole’s establishment was not on the Gerler Map of 1844). Warry was in his early thirties, and boasted 15 years’ experience, meaning that he must have apprenticed and studied in adolescence.

Two years after taking over that business, he proved his expertise by winning an international exhibition medal for his preparation of groundnut or peanut oil (Yangon oil) and arrowroot. Arrowroot was used to treat bowel and stomach disorders, giving some clue as to the intended use of the preparation.[ii]

Despite his bachelor existence, and a rather outrageous sense of humour (of which much more later), Warry was well-respected and entered into politics at Separation in 1860. He was elected to the seat of East Moreton in a by-election in October 1860, and served until the election of 1863. That election, contested by Warry, Robert Cribb, George Edmondstone and William Brookes, was shambolic. The Returning Officer made an error, meaning that the Cleveland poll was not held on the same day. The initial poll’s result was published before Cleveland could vote, and Thomas Warry, at that point coming third, campaigned heavily in Cleveland and won. The result was overturned on the protest of William Brookes, and another poll was held, with Edmondstone and Brookes in the lead, Robert Cribb third, and Warry last. Robert Cribb challenged the result on the basis of apparently misleading printed ballot papers. The third election, on 26 September 1863, resulted in Edmondstone and Cribb winning. The voters were probably quite exhausted by this time. [iii]

Undeterred, Warry contested a by-election in 1864, which William Brookes won. Warry challenged the result, and a second election was held on 13 August 1864. William Brookes won, and Thomas Warry came in last. The man had campaigned in five elections in four years. The day after the vote, Warry became seriously ill, and died at his home on Friday 19 August 1864.

The news of Warry’s death shocked Brisbane. He was only 41 years old and had made his mark on the social and political life of the town. His funeral was widely attended, and the procession paused at the Hospital to allow the many aged and infirm there to pay their respects to the man who had quietly shown them so much help and charity.[iv]

His obituaries gave an insight into the complex character of the man. The Courier described him as possessing a “somewhat bluff and eccentric” demeanour. The North Australian went into more detail:

“With much in his character that was eccentric, and having a strong relish for the humorous and ridiculous, Mr. Warry possessed a disposition capable of true sympathy with all that was exalted and generous, and a delicate benevolence that was in marked contrast to the brasquerie which he frequently put on. Free from prejudice, and with a mind expanded by considerable reading, he could have taken a higher social stand; but an antipathy to shams and restraint, and a desire to mix with the pleasant and cheerful, overcame all considerations of reserve. Notwithstanding many estimable qualities as a citizen and a friend, and a general liberality of sentiment, Mr. Warry had few of the qualifications necessary for political life. The formalities and restraint of a deliberate assembly were irksome to him, and the repetition of arguments and mistakes inseparable from the debates, often caused him to interject jocular comments, which interrupted the propriety of the scene. With large powers of concentration, he made no allowance for its deficiency in others; and frequently attributed sayings and doings to motives different to those which actuated them. Self-reliant, he could not appreciate the value of party concert, and was never to be counted in a division. As a companion and dispenser of justice Mr. Warry’s merit lay in his kindness, his freedom from affectation, and his honesty of purpose. Amongst his large circle of friends, he will long be missed, and many of the commanders of vessels, who have visited the port, will on their return, regret that their old eccentric friend is no more.”

Between 1907 and 1908, the Truth published an old-timer’s recollections of the people buried in the old Paddington cemetery, under the banner “Bygone Brisbane.” Some of the stories were contested by readers, largely those relating to the capture of the indigenous warrior, Dundalli. Amongst the tales of Old Brisbane Town, were two tales of Thomas Warry’s eccentricity, both uncontested by correspondents, that lead to the severed head story.

Thomas Symes Warry was a chemist in Queen-street. He died, unmarried on August 19 1864, aged 42. The stone says. “Blessed is he that considereth the poor.” Also this remarkable verse : —

“’Tis strange that those we lean on most,

Those in whose laps our limbs are nursed,

Fall into shadow soonest lost.

Those we love first are first.

God gives us love, something to love

He lends us, but when love is grown

To ripeness, that on which it throve

Falls off, and love is left alone.”

This Warry was a humourist. On one occasion he induced Billy Brookes to climb a greasy pole in front of his shop in Queen-street. Those were days when Billy was not the severe good templar he became in after years. The pole, climbing scene was exhilarating. Billy, with the aid of sandpaper, on his hands, got up about halfway, and then slid down with great celerity. Then he and Warry went over to call on “Pretty Polly,” at the Treasury Hotel to drink confusion to greasy pole climbing.[v]

The Billy Brookes mentioned here is none other than William Brookes, against whom Thomas Warry stood in many electoral endeavours.

The second story involves a severed head, and muses that the dinner at which it was presented may have been “his best girl coming of age,” which invites speculation that Mr Warry, although he died a bachelor, liked his ladies on the young side.

Tom was a practical joker of unusual type, and a gruesome tale describes the most remarkable of all his performances. He invited the principal citizens to a special dinner, presumably in honour of his birthday, or his grandmother’s death, or his best girl coming of age, or an imaginary legacy left to him by an uncle in Spitzbergen. In the centre of the table was a large round dish under a cover, “I think,” said this peculiar joker, “that we better start on the principal dish.” and he raised the cover to reveal the fresh head of an aboriginal, who had been hanged that morning! It was garnished like a ham, with frilled pink paper, and the thick mass of black hair had a dozen rosebuds inserted here and there. The company first gasped for breath and then some of them fell over the backs of their chairs. Others fell over the doorstop rushing outside, and two fainted. A bombshell could not have scattered that dinner party more effectually. It was Tom Warry’s champion joke. He had induced the authorities to give him the head for scientific purposes, and he explained afterwards that this was in order to settle the great physiological problem of how fright affects various types of men! But Brisbane citizens were clean “off ” Tom’s dinner parties for evermore.[vi]

This was not the head that Thomas Warry was notorious for possessing. That was the skull of Kipper Billy, an indigenous man who was shot dead while climbing the wall of Brisbane Gaol, where he was awaiting execution.[vii] Kipper Billy died on 5 March 1862. Later that month, strange rumours about town caused the wardens of St John’s Cathedral, Henry Buckley and Shepherd Smith, to exhume Kipper Billy in order to see if the poor man’s body was intact. The head was missing. The wardens investigated, and found Lewis Adolphus Bernays, Clerk of the Queensland Legislative Assembly, ready to make a statement that he had been to Warry’s house and been shown a skull by Warry, claimed to be that of Kipper Billy.

Getting slightly ahead of the scandal, as far as published reports went, Thomas Warry took out a polite classified advertisement in the Courier:

My Lord Bishop and Gentlemen,

It having been considered that I was very wrong in obtaining the head of “Kipper Billy” for Surgical and Scientific purposes, I beg most respectfully to express my sincere regret. This apology is tendered with humble cheerfulness, inspired by a conviction that you will consistently follow up the course of Aborigine advocacy, thus auspiciously commenced, by insisting upon similar apologies from those numerous Members of both Houses of our Legislature who are amenable to the charge of having brought many blackfellows into the condition in which “Kipper Billy” was unfortunately found.

I have the honour to be,

My Lord and Gentlemen,

Your most obedient Servant,

T S. WARRY.

To the Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Brisbane, and Henry Buckley, and Shepherd Smith, Esquires.

Brisbane, 15th April, 1862.[viii]

It was an open admission that he had obtained the head, and a not very gracious tip of the hat to the Bishop of St John’s and his parliamentary colleagues. It didn’t have the desired effect. The correspondence that Buckley and Smith had been engaged in with the Colonial Secretary was published in a subsequent Courier[ix], naming Lewis Adolphus Bernays as the individual who had made a statement. The correspondence used the words “revolting” and “abhorrent,” and suggested that Warry should be removed from the register of Commissioners of the Peace pending a criminal investigation.

This was too much for Thomas Warry. He tore into his accusers in print.

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR.

“HEAD-SNATCHING.” Risum teneatis, amici?[x] — Horace. Ride, si sapis.[xi] — Martial.

Sir,– I have lately been brought into a notoriety which I certainly do not covet, but which, at the same time, I cannot consider as discreditable. The matter has been brought about, in both instances, by my having, in my simplicity, mistaken persons for gentlemen who had no claim to be considered as such; and, if I reap no other advantage from recent events than is involved in placing me more on my guard, I shall not have gone through the trifling ordeal in vain.

I notice that, in your issue of Monday last, and also in the Guardian of Tuesday, there appears a lengthy correspondence signed by two persons named Henry Buckley and Shepherd Smith, who style themselves “Wardens of St. John’s, Brisbane;” and also a letter signed by “A. W. Manning,” who would appear, from his communication, to be the Colonial Secretary of the colony, although I was always under the impression that the Hon. R. G. W. Herbert occupied that position.

This correspondence, when divested of all its mawkish sentimentality and absurd exaggeration, simply amounts to this :–That Messrs. Henry Buckley and Shepherd Smith, the humble servants of the Bishop of Brisbane, transformed themselves for the nonce into detectives; that they went out to a piece of ground devoted hitherto to the interment of felons, but which they allege to have been granted to the Church of England for burial purposes; that they there disinterred the body of the unfortunate “Kipper Billy;” that they found the corpse headless; and that, — to use language which ought to be familiar to them, — “from information they received,” (the informer being Mr. L. A. Bernays, a person whom I once remember to have been foolish enough to admit into my parlour on an equal footing with myself), they imagine a “Member of Parliament and a Justice of the Peace,” meaning your humble servant, to be the perpetrator of the so-called “enormity.” Not liking to act themselves in the matter, they call upon the Executive to initiate proceedings against me, but Mr. Manning, in his letter, throws the onus of action upon the “wardens,” and advises them to proceed. The “wardens” reply, — are evidently inclined to shirk the responsibility of taking action, — affirm that they have done their duty in calling the attention of the Executive to the subject, — and then coolly advise that I should be removed from the Commission of the Peace.

I have already said that the correspondence is characterised by much mawkish sentimentality, and I here repeat the observation.-Such a ludicrously stupendous effort at “piling the agony” I don’t remember to have read for many years past; and I can well imagine that, some years hence, when one of these heroes shall happen to meet the other at the Club, and spell over their wondrous composition together, the one will say to the other — nearly as Swift said when he read his own “Tale of a Tub” — “Good God, what a genius we must each have had when we wrote this.” But what does it all amount to? In my opinion, to a ridiculous exhibition of puerility, and nothing more. They (Messrs. Buckley and Smith) aver that the land in question has been granted to the Church of England, but I have good reason to believe that this was not actually the case at the time that the alleged offence was committed; and I presume that, if it had been publicly known, the gaol authorities would not have brought themselves within the reach of an episcopal denunciation by interring the body there. I wonder how often it entered the heads of the “wardens,” — who are both attached to the Hospital Committee, — to enquire into the history of various skulls which are ranged on the shelves in the committee room. I wonder how often “common informers” have afforded knowledge which has led to the prosecution of hospital surgeons in London. I wonder how much Mr. Smith would have moved in the matter if a particular friend of his had been the supposed delinquent.

I find the act with which I am charged alluded to as a “wanton outrage;” an action “revolting to the good feeling of the whole community;” a “repulsive misdeed;” a “disgraceful outrage upon every feeling of propriety.” In the exaggeration of this language, I think I can recognize the “fine Roman hand” of our venerable prelate. I have every respect for that gentleman; I believe him to be actuated by pure motives, as far as his own conception of things is concerned; but I cannot comply with his request that I should publish an apology in all the English papers, in order that people at home may see how ardently he is striving to effect the evangelization of the “poor blacks.” How this noble end can be attained by hounding his Churchwardens on to ferret out the alleged exhumer of a black’s remains, I am at a loss to know, — but, not professing to be acquainted with the ins and outs of episcopal theology, I must leave the Bishop to enlighten me on this point.

Once, and for all, I most distinctly refuse to acknowledge my accountability, either to the Bishop or the “wardens of St. John’s,” for whatever I may have done. I am prepared, when called upon, to defend myself in a legitimate way, but object most strenuously to be “called to the bar” by persons who are, without figure of speech, public servants. So long as I perform my duties as a magistrate and member of parliament to the satisfaction of the public in the one case, and of my constituents in the other, I consider that I fulfil all that is required of me, and I object to having my public capacities violently dragged into the assistance of my calumniators. I can understand the animus by which one of them, at least, is actuated; and I can understand, also, the influence which is at work behind the scenes. For each of these I care not. As an independent citizen, I claim to be judged in this matter, and I await with patience further action on the part of the “wardens.” Future correspondence in the public prints I shall leave to the consideration of my apprentice; and shall, in future, endeavour to observe more strictly the advice of a lamented parent, and only admit “respectable people” into my companionship.

I remain, Sir,

Yours, obediently,

T. S. WARRY. Brisbane, April 23rd, 1862

The indignant letter turned out, surprisingly, to be the last salvo in the war over the misappropriated skull. St John’s quietly fenced in and declared the burying ground. The news rippled across the pages of the weeklies, and then faded from view. Thomas Warry continued to serve in Parliament until losing the election of 1863, and dying a week later. One imagines that relations between the Member for East Moreton and the Clerk of the Legislative Assembly were decidedly chilly during the final sittings of 1862-3.

It was never suggested that Thomas Warry had actually dug up and mutilated the corpse of Kipper Billy, and it is not known where the skull went after being exhibited at the Warry house. This was another instance of the remains of an indigenous person being treated as a curiosity, or at best a museum exhibit in the name of “Science.” More sadly still, Kipper Billy need not have died. Billy Horton, his co-accused was pardoned and released from gaol shortly afterwards, and Kipper Billy, had he lived, would have received the same treatment. Nobody thought to deliver a posthumous pardon to Kipper Billy until very recently.

If the story of the freshly-executed head at the dinner table is true, who might it have been? Kipper Billy did not live to be executed, leaving five possible identities – indigenous men who were hung at Brisbane during Thomas Warry’s residence here. The men were:

Davy, executed 24 August 1854 at Queen Street Gaol,

Dundalli, executed 5 January 1866 at Queen Street Gaol,

Chamery, executed 4 August 1859 at Queen St Gaol,

Dick, executed 4 August 1859 at Queen St Gaol, and

Georgie, executed 5 December 1861 at Petrie Terrace Gaol.

It is unlikely to be Davy, because Mr Warry was quite young and new to town in 1854, and a person trying to make a good impression on his new townspeople might refrain from desecrating a corpse, at least at that early stage. It is also doubtful that it was Dundalli – the man was famous, and the story would have included mention of his name. That leaves the co-accused Dick and Chamery, and Georgie. I hope that the story is just the product of an old-timer’s colourful imagination – where a true story merges with a yarn.

There is another famous souvenired head story that it may have merged with in the author’s memory – that of Thomas John Griffin, former Gold Commissioner, whose grave was robbed of his skull after his execution in Rockhampton in June 1868. Another social notable, this time at Rockhampton, boasted of having the felon’s skull in his possession for years afterwards. Presumably also in the name of ‘Science’.

[i] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 8 April 1854

[ii] North Australian, Ipswich and General Advertiser (Ipswich, Qld. : 1856 – 1862), Tuesday 12 August 1856

[iii] Thomas Symes Warry – Wikipedia

[iv] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Saturday 20 August 1864, page 4

[v] Truth (Brisbane, Qld. : 1900 – 1954), Sunday 12 January 1908

[vi] Truth (Brisbane, Qld. : 1900 – 1954), Sunday 8 March 1908

[vii] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Thursday 6 March 1862

[viii] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Wednesday 16 April 1862

[ix] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Monday 21 April 1862, page 2

[x] “Can you help laughing, friends?”

[xi] “Laugh if you are wise.”