Maryborough, near the river. Sunday 06 April 1879.

THE NEIGHBOURS

By his estimation, it was around 4 am when Mr Holme was woken by the sound of raised voices on the other side of the river. It sounded like a scuffle, with a woman crying out, “Stop it! Oh, stop it!”

There was a loud splash in the water. Then, nothing. The commotion seemed to be coming from Ramsay’s Sawmills in Kent-Street, which had some workers’ cottages nearby and a shed close to the river.

Other neighbours on the Mill side of the river were convinced that the scuffle took place in Kent Street, about 160 metres from the riverbank. Other residents heard nothing at all that night.

THE NIGHT-WATCHMAN

The elderly night-watchman at Ramsay’s, Mr Buffey, heard some noises in the early hours, but they were muffled by the barking of a dog. He did notice a dark-skinned man run out of the Mill’s shed, who, when asked what he was doing, said “Me no fight, me been sleep,” before running out of sight.

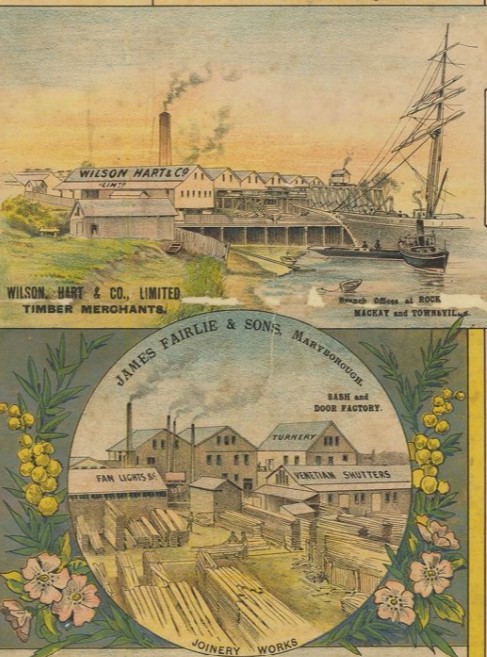

Businesses on the river, c 1879

Buffey had been reading at the time of the disturbance and decided to put out his light and get some rest. It was quiet. There was no-one about.

MR AND MRS AITKEN

The Aitkens resided in a workman’s cottage near the Mill, where Robert Aitken worked as a drayman. The couple had been married for over a decade and had lost three children in infancy and had four living children. Their youngest, Robina, was only a few weeks old. Elizabeth Aitken was still recovering from her confinement when, on the morning of Sunday 6 April, at about 2 am by her estimation, she was woken by cries of distress and rapid tramping of feet outside their cottage. Fearing that someone could be hurt, she woke her husband. Robert rose immediately without dressing, and ran to the front, then the rear, of the house and out of the back door. She never saw her husband again. There were no more noises outside.

At daybreak, the police were faced with a distraught mother of five who had not heard from her husband since he went outside to investigate the noises in the night. There was no trace of Robert Aitken anywhere on land, and the working theory formed was that Aitken had gone outside to stop a man mistreating a woman, and had either been killed in the process, or had fallen into the water and drowned.

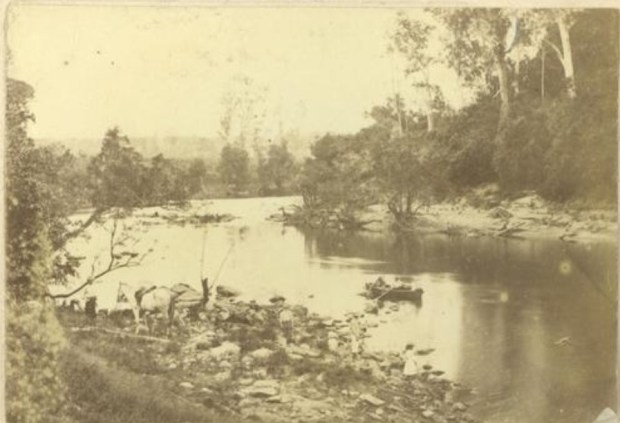

The river at Maryborough, c 1863

From the accounts of a woman crying out, the police also surmised that a woman may also have died, possibly at the hands of the dark-skinned man who ran from the shed. The man Mr Buffey saw was either Polynesian, Asian or Indigenous, he wasn’t sure.

The shed was examined and showed signs that someone had been sleeping there very roughly, with shingles arranged to form a pillow. There were the tracks of bare feet running through the dirt towards a fence, but the trail was lost on the other side of the fence where grass grew.

Inspector Lloyd ordered his men to drag the river, which they did repeatedly in the coming days. Indigenous divers were sent in when the presence of mud and tree roots made dragging impossible.

People in the neighbourhood were questioned. Who and where was the woman heard calling out, “Stop it! Oh, stop it?” There was no report of a missing woman, and as the Queenslander’s reporter put it, roguishly, “the researches made officially at a house of ill-fame which exists in the neighbourhood have led to the conclusion that none of the inmates are in any way compromised.”

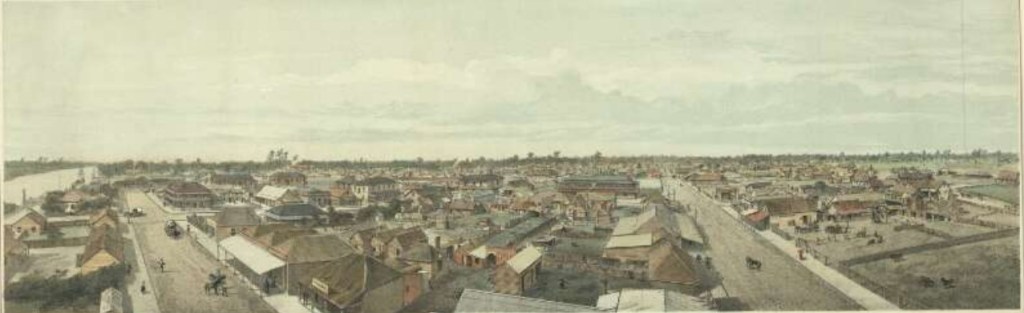

View of Maryborough, c 1879

Days dragged on with no leads. The river was searched over and over. They examined the life of Robert Aitken. He was a sober, industrious man of nearly 40 summers, who had been married to Elizabeth Reid since 1867. They had suffered the loss of three of their infant children, a boy named Arthur and two girls, both named Elizabeth after their mother. Their remaining children were their pride and joy. Robert had been an Oddfellow (a member of a fraternal guild of that name). Elizabeth Aitken was distressed and left almost destitute by her husband’s disappearance. She blamed herself for getting him out of bed to investigate the noises.

Then, people began to speculate, as they will inevitably do when a mystery presents itself. Was it murder? Was it an accidental fall into the river? Was it suicide? Was there any proof that Robert Aitken had been home at all that night?

The most popular theories were:

- Suicide: Robert Aitken might have been in financial trouble. “It has since transpired that Aitken was in a state of feverish excitement through monetary embarrassments, which, with certain facts gleaned from the children, lends colour to the above assumption,” reported the Queenslander. The cries heard may have been Elizabeth Aitken trying to stop her husband drowning himself.

- Murder by indigenous people: An early belief was that “the blacks” had killed Aitken and disposed of his body. This assumption was due to the presence of the dark-skinned man who ran from the shed that night. The police abandoned that theory early in their investigation due to a complete lack of any evidence.

- Murder by one or both of the people involved in the disturbance near the river. That question remained open, but there was no evidence to prove or disprove it.

- Accident: Robert Aitken had accidentally fallen in the river. That theory also remained possible.

- Staged disappearance: Again, from the Queenslander “The master of one of the timber vessels plying to and from Ramsay’s wharf asserts that he saw the missing man, Aitken, in Brisbane about ten days ago.” The Telegraph also reported that Robert Aitken’s father had disappeared “many years ago,” without leaving any clue as to his fate. This theory was dismissed by police, who investigated the claim of a sighting, and found that the person who had said it was only speculating on what might have happened and had no actual information to offer.

Answers were never found to any of the questions. The body of Robert Aitken was not recovered, and at the end of May, the Oddfellows Society paid Elizabeth Aitken the death benefits it held in Robert’s name. She was near destitution, and there was by this time, no doubt that Robert Aitken had died. No further evidence was ever found in the case.

Elizabeth Aitken raised her children well, with prizes being awarded in school to Robert junior. That can’t have been easy to achieve with home life dominated by the loss of his father. Elizabeth passed away in 1932 at the grand old age of 88.

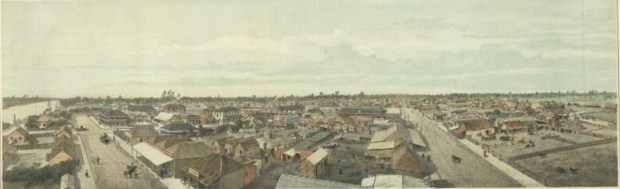

By the river at Maryborough, from the Customs House Hotel

The river gave up another victim some weeks after Robert Aitken’s disappearance, and that is another tragic story….

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947)Tuesday 8 April 1879 Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Saturday 19 April 1879 Week (Brisbane, Qld. : 1876 – 1934), Saturday 19 April 1879 Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 – 1939), Saturday 26 April 1879 Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 – 1939), Saturday 10 May 1879 Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 – 1939), Saturday 24 May 1879 Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1850 – 1932), Saturday 28 June 1879. Photographs and images from the collections of the State Library of Queensland and the National Library of Australia.