NOTABLE BRISBANE PIONEERS – ARTHUR BULGIN

“The emigrants per the Chaseley resemble in character and views those per the Fortitude. They consist, first, of respectable families, going out to settle on small farms, under the auspices of the Company, and to grow cotton and other tropical productions, in addition to those of Europe; second, of mechanics of various handicrafts, as bricklayers and plasterers, carpenters, blacksmiths, &c.; and third, of persons of the class of labourers, both married and single, including several young men, of a superior class in society, and of active and enterprising character and habits, who will be happy to take employment on the pastoral establishments of the district.” JOHN DUNMORE LANG

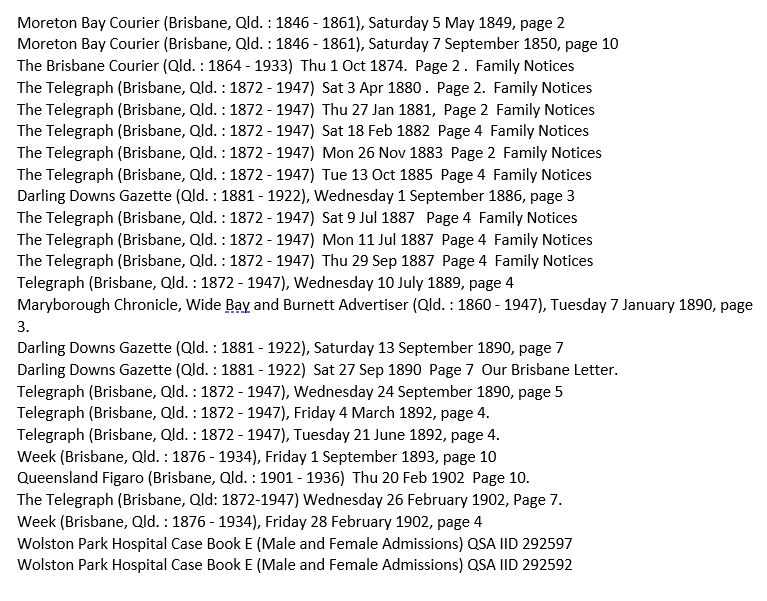

Arthur Bulgin (1843-1902) came to Brisbane as a boy in 1849 on board one of Dr Lang’s immigrant ships, the Chaseley. His father Henry became a successful auctioneer, before transitioning into public administration. His mother Jane ran a small, rather select school.

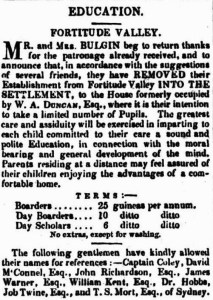

Mrs Bulgin’s school grew and prospered through to the mid-1850s, and was probably one of the better schools in Brisbane Town. Any number of respectable and pseudo-respectable ladies and gentlemen advertised their willingness to take pupils over the years, but most left town in haste and with unpaid fees and rents. (The earliest school in Brisbane had operated for the children of soldiers, convict children and servants’ children, and closed with the penal colony in 1842. A Catholic school was set up in 1845, and other denominations followed; all were fee-paying, and many children simply went without any schooling at all until the National School system was implemented after Separation in 1859.)

Arthur Bulgin and his five siblings no doubt received sound schooling and all of the life lessons of industry and decency that good Chaseley immigrants could provide.

As a young man, Arthur entered the public service, and performed creditably for a number of years. He wrote a fine hand, kept records well, attended church and was well-liked by all who knew him.

In 1865, he spent three months in Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum, suicidal and unwilling to eat. He improved out of all sight once he began eating regularly, and was discharged in good health, and returned to his work and home.

Ten years later, he had a relapse and was admitted for several months and discharged. This pattern was repeated each year until 1879. He was still experiencing trouble eating, but had added fervent religious beliefs and a conviction that he was the rightful claimant to the throne of England to his symptoms. Once able to commence eating properly, and coaxed away from his books, he would improve immeasurably.

“He asserts that he is superior to the Governor both in birth and education, and that he has more right to the throne of England than the Queen has.” Casebook.

Things looked up for Arthur Bulgin after 1879. His hospital admissions ceased, he met and married Mary Collum, and they started a large family. He still worked industriously as a civil servant in the Crown Lands Office, and he spent over a decade living as a harmless eccentric who had a few pretensions to nobility.

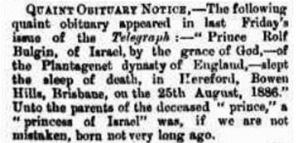

Their first three children (Jane 1881, John 1882 and Carl 1883) were announced to the world in normal terms (born to the wife of Arthur Bulgin in Hereford, Brisbane). The fourth baby, Rolf (born in 1885) was announced thus:

On the 12th October 1885 in Hereford, Brisbane, lady Bulgin, queen, of Israel, by the grace of God, of a son (prince Rolf).

Sadly, the child only lived a year, and the Darling Downs Gazette was struck by the wording of the death notice:

Son Frank arrived in 1887, and was announced by a quite ordinary birth notice in the Telegraph on Saturday 9 July 1887, then a more florid announcement the following Monday of the birth to “Lady Bulgin” of a son (Lord Frank).

Soon, Arthur was inserting memorials in the papers to his long-deceased parents, using the titles Lord and Lady before their names. It would seem that this idea of unrecognised nobility was not limited to Arthur Bulgin – his brother Henry, who resided in New South Wales, was popularly known as “Lord” Henry. Perhaps somewhere in the Bulgin ancestry there had been a high-born connection, or Henry and Jane had raised their children with the idea that they were a little bit higher and mightier than your average Lang immigrant. It’s quite unusual for two brothers in different colonies to insist that they were Lords. Another brother, Lewis Bulgin, had thrived in the north of Queensland, enjoying a number of civic appointments, but did not seem to have claimed a title at any point.

Two more sons were born to Arthur and Mary Bulgin: James in 1889, and Fritz, who was born in 1892 and died in 1893. 1890 would be the year that Arthur Bulgin came to the attention of Queensland, beyond his family and friends. In January, the Brisbane Letter of the Maryborough Chronicle announced with great glee:

We have here in Brisbane a splendid specimen of the genuine British religious ‘crank.’

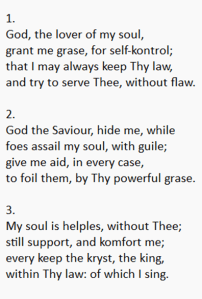

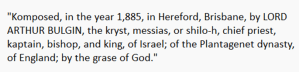

“Lord” Bulgin had drawn attention to himself by publishing some political “manifestos,” which included some miserably composed and bizarrely spelled poetry, which was shared by the Chronicle:

The man was clearly as fond of the letter K as the Kardashian family.

“The man’s chief idea is that he is a singular compound of the race of David, and of the Plantagenets. He sees in himself the fulfilment of all the old Testament prophesies of the Messia or Christ, while, if he had his rights, he would also at the present moment be upon the throne of England. This is not all. His wife is of illustrious descent, too. She is the sole surviving representative of the Virgin Mary, and from all accounts, she bears the obviously rather remarkable honour as unassumingly as can be expected.” (Maryborough Chronicle.)

At that stage, he was still a harmless, although increasingly well-known eccentric, but in September 1890, the Lands Department suspended him because his work had started to suffer, and they couldn’t ignore his behaviour any longer. This had a disastrous effect on Bulgin.

Less than a week later, Arthur Bulgin appeared in Court, charge with abusing passers-by at Central Railway Station. In those days, it seemed, highly prominent men about town frequented the platforms, and poor Arthur managed to harass Sir Thomas McIlwraith and John Heussler, as well as an entire smoking carriage.

Brisbane Central Station. Smokers and politicians were verbally harassed within its precincts.

“Don’t wave your arms about. That’s snobby. Carry your hands like a gentleman, Sir Thomas. Don’t be snobby,” which was greeted with a tolerant smile by the former Premier.

Mr Heussler had not enjoyed being called “Lord Theophilus” and upbraided Bulgin, who replied that he would “bear no insolence by a German Jew.”

The passengers in the smoking carriage were “making dirty stinking snobs of themselves and were pests to society.” He declared that he would try by the help of God to abolish the habit. (Mr Bulgin was a century ahead of his time with these sentiments.)

The Station-Master was called and Mr Bulgin was removed from the precincts. The Magistrate, Mr Pinnock, suggested that Bulgin hire a hall and give lectures, and fined him 10 shillings. Mr Bulgin considered it his duty to protest.

Still, the Lands Department was able to keep him in employment until a series of budget and staff cuts in 1893 gave them the excuse to dispense with his services permanently. To be fair, the Colonial Botanist, P.M. Bailey was retrenched, along with eight other clerks.

Arthur Bulgin’s eccentricities gradually descended into serious mental illness again, and he passed away in 1902. His death left Brisbane society bereft of a man who, when he was not suffering, was a slightly quaint but well-loved figure, who had managed to raise a large and happy family. He was another lost link to the era of Lang’s immigrants.

1 Comment