Education from the convict era to Separation

The Convict Era

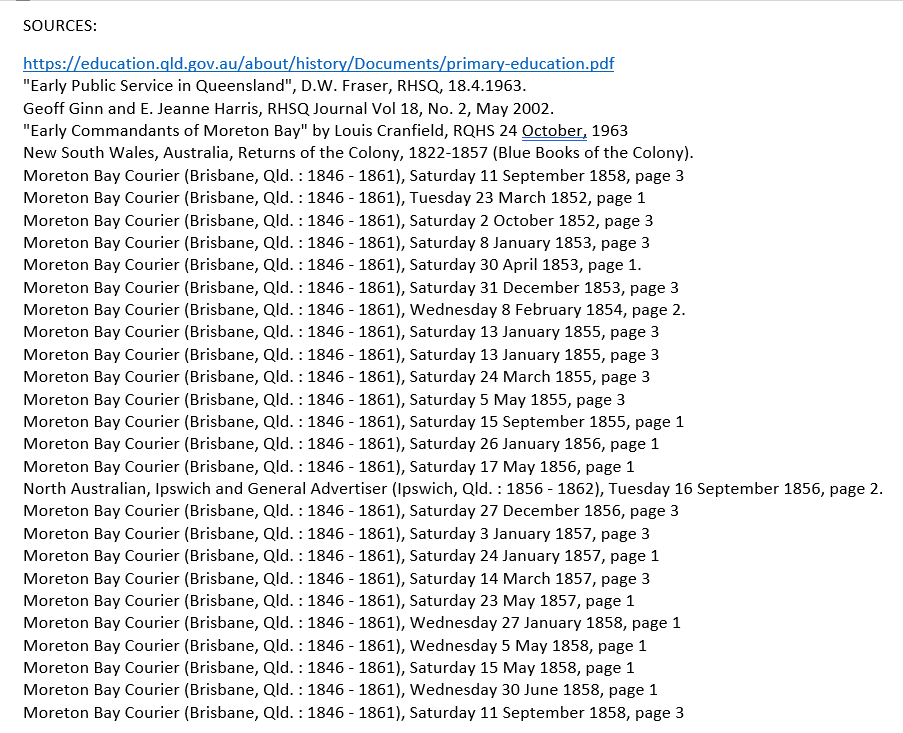

The first European school in Queensland was free, open to all, and had a very low student-to-teacher ratio – just what parents would hope for in a State School today. It was the Moreton Bay penal settlement free school, which opened in 1826. It catered for the children of the military and civil servants who ran the settlement, and inevitably, the children of the convicts confined there.

Mrs Esther Roberts had the distinction of being the first teacher in Queensland. No doubt, conditions were primitive for Mrs Roberts and her charges – during her tenure, the first buildings were erected, and resources were scarce. Not to mention the presence of men in leg-irons, cursing their way through their labours in the heat of the sub-tropics.

The number of students under the care of Mrs Roberts wasn’t recorded in the Blue Books, but it did mention that the “Madras” method of instruction was used. The “Madras” or Monitorial system of education evolved through – aptly – the colonial expansion of European cultures. The basis of the method was to devolve some of the teaching duties to the brighter children (monitors) in the group, who could then pass on information they had learned to the other students. It was referred to as “Madras” because the British army standardised the practice in the very British-sounding Military Male Orphan Asylum, which was located guess-where.

Mrs Roberts was followed by Mr MacGinnis, who saw his class sizes rise from 18 to 30 children, and in the 1830s the Blounts and Sergeant Cleary were handling classes of more than 30 children. (The Blue Book was anxious to point out that Sergeant Cleary was not paid a teaching wage, the man was a paid soldier after all.) The German Mission taught its own pupils, and Tom Petrie recalled being instructed by an educated convict known as “Peg-Leg Kelly.” Young Petrie became a learned adult, so Kelly must have imparted at the very least the basics of a sound education.

The decline and closure of the convict settlement can be seen in the late 1830s and early 1840s, with Mr Asbury teaching 6 children in 1842 – the year the settlement was closed, including the school.

Free Settlement

Brisbane Town and the surrounds were being opened up to free settlers, but had no organised system of education to offer their children. The military still had their children in town, and a teacher to cater for them, but the civilian population found many of the basic facilities (schoolroom and hospital) were not open to them.

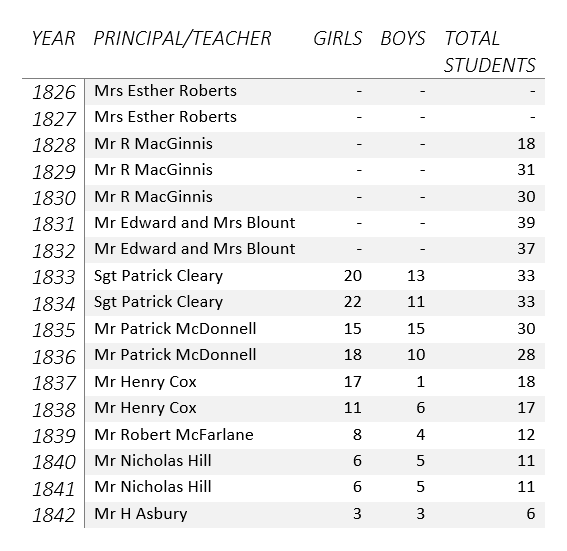

Corporal Lesbie of the 99th Regiment arrived in 1845, and was permitted to include civilian children in his classes. His reassignment in 1847 left a small community bereft, and a public testimonial was printed in the Moreton Bay Courier:

From 1846 to Separation in 1859, a parade of ex-clergymen, redoubtable spinsters and respectable wives operated schools in Brisbane and the surrounds. Some were almost painfully genteel, others vaguely paramilitary, and a few survived for several years. There had been two private schools in 1843, 1844 and 1845. In 1846, with the Courier up and running, competition for the parental shilling was heating up.

THE undersigned begs leave most respectfully…

The first to advertise his services was Mr D Scott, who decided to open a school in the room above Mr Zillman’s store in 1846. He advised that he “had but recently risen from a bed of sickness, and being unfitted for more laborious exertion, yet anxious to render himself useful to his fellow-creatures, trusts that in his endeavours to impart useful religious knowledge to the young, he will meet with the kind support of the public.” Hardly an introduction to inspire confidence.

In September 1846, Mr W.H. Kilner, who had been Second Master at Sydney Grammar in a previous life was prepared, if he met with sufficient interest, to offer “instruction to young persons and adults in the higher branches of Education.”

A Miss Eliza Newman at Kangaroo Point was anxious to offer the young ladies of that area instruction in “Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Grammar, Geography, History, plain and fancy Needlework.” Presumably, they would leave her care ready to create a replica Bayuex Tapestry whilst balancing the grocery accounts.

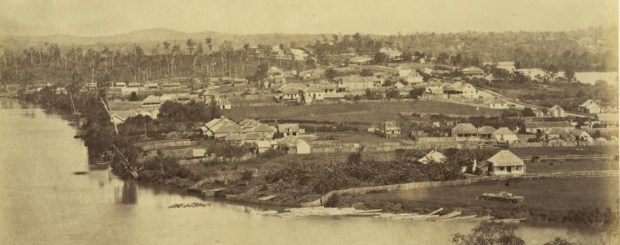

Kangaroo Point, 20 years after Miss Newman tried to instruct pupils in not one, but two, types of needlework.

The Blue Book of the Colony for 1846 showed that there was a Catholic School under the tuition of Mary Bourke (22 boys, 13 girls), and four private schools with 22 boys and 14 girls.

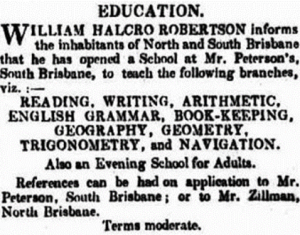

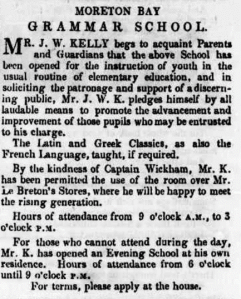

In 1847, the prospective educators were getting serious. Mr Kelly opened a Grammar School. Above a shop. At least it offered classical languages. Mr William Halcro Robertson offered trigonometry and navigation, as well as the three Rs. (Somehow I think that his school was targeted to the masculine corner of the market.)

None of these establishments lasted very long. Miss Newman’s educational style was too ornamental for the small, non-ornamental population of Kangaroo Point, and Messrs Kelly and Scott did not have to look for more suitable locations for their schoolrooms. Mr Robertson was the sole survivor.

Lang’s Immigrants, Mensuration and Use of the Globes

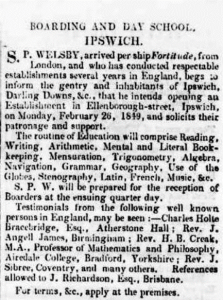

The arrival of Lang’s immigrants in 1848-9 created a market for decent schooling, as well as the means to provide it. Mr Welsby conquered Ipswich with his curriculum and his testimonials.

The ailing Rev. T.W. Bodenham and his good lady wife offered instruction for a few YOUNG LADIES at Kangaroo Point. When he recovered, he was summoned back to Sydney, but left a favourable impression on the population of Brisbane, based on the flowery Address published to mark his departure for the big smoke.

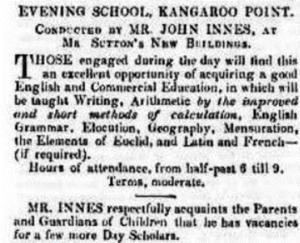

Mr John Innes decided to fill the void at Kangaroo Point with mensuration, Euclid and French (if required). Unlike Mr Welsby, he did not advertise instruction in “use of the globes.”

In Elizabeth Street, Mrs Bowrey was offering instruction to young ladies in the usual branches of “polite English Education,” to day students and a limited number of boarders.

In 1850, a Mr W Shaw at Ipswich offered a quite alarming-sounding curriculum (mercifully for six months only). I am leaving his capitals intact:

“Young Ladies who attend the Day School are taught MARCHING DRILL and are SET UP.” Set up for what, he does not specify. For the Young Gentlemen, there were the outdoor pleasures of “RIFLE EXERCISES and Cavalry and Infantry Sword EXERCISES.” The Charge of the Light Brigade was four years away, but by God, Mr Shaw would see to it that the children of Ipswich, Queensland would be ready to take part. He also taught writing and arithmetic.

At the same time, a few powerhouses of respectable private education emerged. Mrs Jane Bulgin, Mrs J Cooling, Mr H Stowell, Mrs Storey and Miss Lester set up their shingles and were prepared to instruct pupils (including limited boarders) in various branches of a genteel English education.

Mrs J Cooling added drawing, watercolours and calisthenics to her curriculum. Mrs Bulgin had a Professor of the Pianoforte at her disposal. Mr Stowell actually conducted examinations and gave academic prizes. Miss Lester was prepared to instruct in music, dancing, singing, drawing, French, and use of the globes. Mrs Storey offered “Careful, Moral and Religious training”. Mrs Storey and Miss Lester joined forces towards the middle of the 1850s, moving to larger accommodations, and offering to instruct in “the usual branches of literature and the current accomplishments of the age.” They powered through to Separation in this manner.

Quite a few private schools still tried to attract the public and failed quickly. The Rev. James Carter (late Curate of St. James, Sydney, mind) suggested that he could cure Brisbane Town of all its heathen propensities, starting with the children. “The leading object of the undertaking is to promote sound and enlightened education upon Christian principles, in Brisbane and the surrounding country, where, at present, a want is felt of the higher branches of instruction.” Didn’t work.

The (to modern eyes) unfortunately-named Miss Wookey could not attract pupils to her premises in South Brisbane, despite having attended the Diocesan Training College in Salisbury. Mr Keane couldn’t attract enough patrons to his Select Boarding School, located in the glamourous-sounding Cleveland Paddocks, despite its being “one of the most eligible localities in the Colony for studious retirement and healthful recreation.”

The National School and Separation

There was in existence a National Board of Education, set up by Governor Fitzroy in 1848, when New South Wales pretty much was the nation. They were secular, fee-paying establishments, but had a standardised curriculum and were based on the model of the Irish National Schools. National School textbooks were available at all stationers for parents who wished to instruct their little ones at home, or who were forced to do so by distance from settlements.

A salary and subsidy scrap with the Lord Bishop of Newcastle led Mr James Gray to resign from St John’s Church of England school, and set up his very own version of the National School in Brisbane. In no time, he had over 100 students, and was able to offer accommodation for another 30 in 1858. (There had been National Schools in Warwick and Drayton for nearly a decade.)

In December 1859, Queensland became a separate Colony, and was able to legislate for its own educational needs. Fee-paying National Schools were incorporated from New South Wales, and the administration of non-secular education was supervised. A decade later, fees were scrapped for National Schools. In 1875, the breakthrough came – primary education was made compulsory, secular and free, and was administered by an educational department. Mrs Roberts and her successors at Moreton Bay, who offered free education to all children, would surely have approved.