Judge Innes, Rockhampton District Court, 17 June 1867, sentencing a bigamist.

Bigamy in Colonial Queensland – PART ONE

Moreton Bay Courier, 1859

Whoever W.H.G. of Nanango was, he or she would have done well to take note of Brown’s Billy’s warning in the Courier’s classifieds in October,1859. Bigamy attracted stiff sentences of penal servitude, not to mention public disgrace.

Until the 1860s, Queensland had few bigamy cases. The population was small, communication between places was slow, and paperwork was scant. The twin population-builders of transportation and immigration also served to strand spouses on opposite hemispheres, often with no idea whether their lawfully wedded ones were alive or dead. Doubtless, quite a few took advantage of the tyranny of distance. One could disappear into one of the new townships and continue a new life with the partner of one’s choice, perhaps even hoodwinking a colonial parson to make things look good.

“If this should meet the eye of JAMES DUNWILL (or any person acquainted with him), who came to Port Adelaide in 1838 or 1839, his Wife is now living on the Darling Downs Moreton Bay District married to a man named FAIRCLOTH or MURPHY. She is married in her maiden name, ANN DAVID.” Moreton Bay Courier, 1851

Scandalous reports came from the English and American papers of low behaviour in high places. Sir Eardley Gideon Culling Eardley, bart., famously married ladies on both sides of the Atlantic, and was convicted and imprisoned for of bigamy. In America, the activities of one Brigham Young horrified the newspaper-reading public, at the same time providing copy for pun-makers. Imagine that many mothers-in-law.

Bigamy: A generous way of making two women happy instead of one.

Toowoomba Chronicle and Queensland Advertiser, 1863

By the early 1860s, the courts of the new colony of Queensland found themselves confronted with an increase in crimes against matrimony. Population growth, telegraphic communication and the greater mobility afforded by opened roads and railways increased the chances of bigamous unions being discovered. The consequences were almost always painful.

The MacDonald Case

On 10 June 1862, a man named William James MacDonald married a publican’s widow – Emily Sarah Ann Wakefield – at Rockhampton, in a ceremony presided over by the Rev. Samuel Savage. Local worthies noted with disdain that Mrs. Wakefield had not even spent three months deploring her loss before remarrying, and they were equal parts horrified and delighted when another Mrs. William James MacDonald arrived in town per the aptly-named Boomerang to see her errant husband.

What followed caused mirth, then horror, followed by public outrage. Kate Theresa MacDonald, the original wife, was seen trailing miserably behind her husband, who paraded openly with Emily MacDonald in the Rockhampton streets. Kate, it was observed, was an attractive woman, albeit somewhat the worse for misery and drink. Emily was “rotund and rubicund” (fat and red-faced I imagine), and it was felt that she had her eye on William’s property holdings at Barandoon. William had been tippling himself for some time prior to his second marriage, and was caught between his two angry wives.

The Bigamy Case Extraordinary

Emily MacDonald charged William with bigamy, and he was arrested with punishing sureties to bail, which he could not meet. At the first hearing of his case, the Rev. Savage gave evidence about declining to hold an earlier marriage ceremony because William was so drunk that he could not answer basic questions. By 10 June, William was in sufficiently good repair to go through with the ceremony, and the deed was done. The case was remanded for evidence from Sydney about William’s marriage to Kate.

On August 8 1862, Kate MacDonald, in a state of great distress, broke a tumbler in her hotel room and cut her throat. Despite medical attention, she died hours later.

At the inquest, witnesses at the Freemason’s Arms Hotel described the dying Kate begging that “the big woman Mother Wakefield” not be allowed to have anything to do with her two children, and complained of threats and beatings at the hands of Emily and her (Emily’s) family.

William MacDonald was produced as a witness to identity, and swore that he could not identify the remains. He knew of a barmaid named Kate Theresa Green at Maitland, where he had resided previously, but didn’t think she had any family, and didn’t think that the dead body was that of Kate Theresa Green. He didn’t know who the woman was.

James Smith, late of Maitland, was able to identify the deceased woman as Kate Theresa MacDonald, nee Green. When he attended at the hotel, he heard Kate’s dying declarations about marrying MacDonald in 1841, and promised to give Kate’s children a treasured photograph.

The verdict of the jury spoke for the town of Rockhampton:

“That the said Kate Green, alias McDonald, died from a cut in the throat made with glass while in a state of insanity.” A difference of opinion existed amongst the jury-men with reference to the following rider, which was appended to the verdict, nine of them being for it, the other three wishing it to be put in a milder form—” We believe that it was through the disgraceful conduct of Mrs. Wakefield and Mr. McDonald that the late Mrs. McDonald committed the rash act of cutting her throat.” Rockhampton Bulletin, 9 August 1862.

“The mob behaved in the most praiseworthy manner.”

The excitement of a major scandal hitting town, then the horror of the suicide of the wronged wife turned to disgust in the feelings of Rockhampton’s citizens. Some of the noisier and more excitable ones decided that it was time to mete out some summary justice to the sinners.

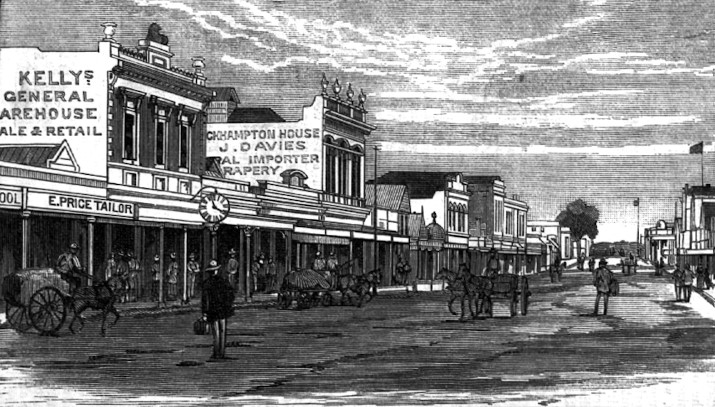

East Street Rockhampton (sketch 1885).

The Maryborough Chronicle‘s reporter estimated the mob that surrounded the second Mrs. MacDonald’s house at between 300 and 400 people. The Courier made no estimate of the size of the crowd, but reported that “stones, brickbats and bones” were used to smash the windows of her house, and that she took refuge in the police lockup. The couple were burned in effigy outside the Fitzroy Hotel, which had been the Wakefield’s premises in happier times.

“Special constables were sworn in to protect life and property, but their services were not required, the mob behaving in a most praiseworthy manner.”

The Courier, Brisbane, Friday 15 August 1862

Four months later, William MacDonald was still in custody in the Rockhampton lock-up, unable to raise the sums for his sureties, and the police still did not have the paperwork from Sydney that would prove his first marriage. An application was made on his behalf for a rule nisi to release him from custody. Emily MacDonald had withdrawn her bigamy complaint. There were no further protests, and MacDonald was released.

The next time Mr MacDonald was mentioned in the press was the final time – William James MacDonald, Esq. of Barandoon Station (second son of John MacDonald, Esq.) died at his residence in Rockhampton on 22 March 1863.

And the first marriage? He had most certainly married Kate Theresa Green (aged 19, born in Roscommon, Ireland) in Sydney in 1841. A Reverend Allwood had conducted the service. They had two children together. Had the contact between the police in two colonies been more efficient, that proof would have been available to convict him. Perhaps that was what William MacDonald feared would happen when he claimed that he didn’t recognise the woman lying in the morgue at Rockhampton.

1 Comment