Bigamy in Colonial Queensland – PART TWO

Annie Clarke must have been quite a gal. She scandalised three colonies, underwent at least six marriage ceremonies, and created news wherever she went. Who she actually was is hard to pin down, probably because of the number of husbands and surnames she racked up in a hectic quarter of a century.

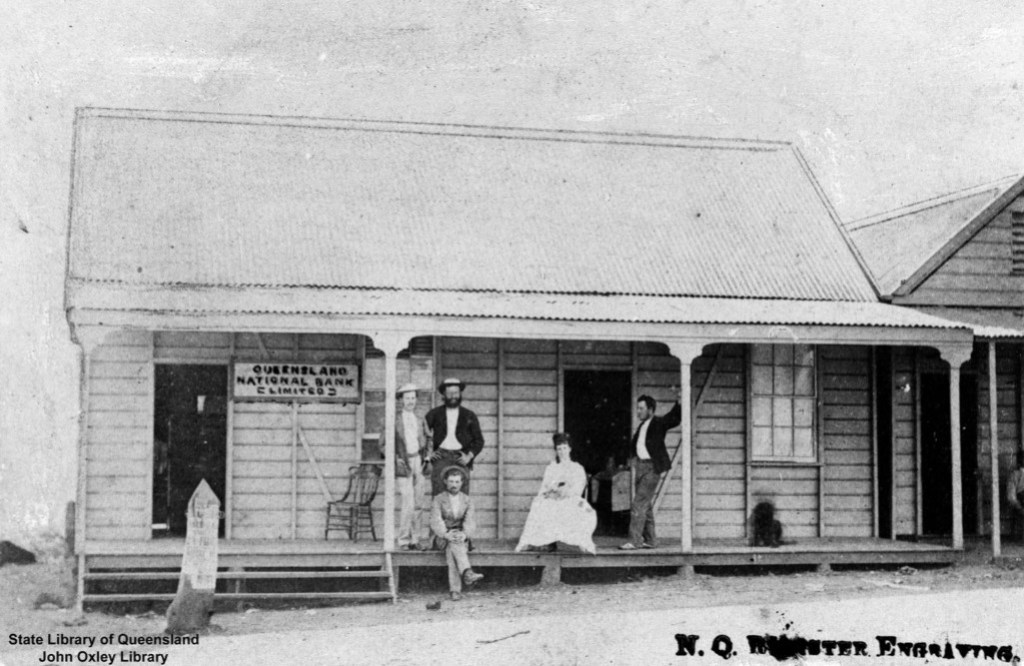

Annie first encountered notoriety in the mining town of Millchester, near Charters Towers, in the early 1870s. Gold had just been discovered in the area, and it attracted the usual suspects – diggers, fortune-seekers, profiteers and ladies with an eye to the main chance.

In May 1874, one such lady, Annie Clarke, applied for and was granted the publican’s license to the Tattersall’s Hotel in Millchester. In her public notice, she stated that she was not married, and had never held a license before. Soon, she was the toast of the goldfields. She had some competition from a formidable-sounding rival, Miss M. Hayes, who offered “none but the best brands of Spirits, Wines, Ales, and Liquors”. Annie’s establishment offered a billiards room and rather a lot of interesting nocturnal activity.

Get out of town!

The first sign of trouble came on Sunday 26 September 1875, when Annie Clarke came back to the Tattersall’s Hotel after a night away and found her living quarters had been broken into, and money and personal items stolen.

Jonathan F. Labatt and William Charles Ross (nephew of the man who ‘kept’ Annie) were charged with the offence of breaking into a dwelling in the night with intent to commit a felony and were brought up before the Police Court. They were young men of reasonable reputation about the town and had retained a solicitor who set about making the case more about Annie’s morality and marital status, than refuting the facts of an indictable offence.

Annie obliged by stating that she had married a George Hansen in Dr Lang’s Church in Sydney some six years earlier, but left her husband after hearing he was already married. She did not know if he was still alive. She was open about her relationship with W.A. Ross.

Several fairly colourful Millchester residents who had been about at the time of the offence gave evidence on the activities of the defendants. Their characters and habits were easily picked apart by the defence. The prosecutor had asked if a person of imperfect morals could still be the victim of a crime. Silly question – even the judge spent the better part of the summing up decrying immorality than pointing out the facts for the jury. The defendants were found not guilty, although the judge told them they had a very close brush with the law.

A civil court case shortly afterwards taken out in the name of her absent husband had her testifying to having married one Hans George Hansen in Newtown about six years earlier. She rather cleverly excused the change in her story by saying that she never swore she married in Sydney, she swore that she thought she married in Sydney. No Mr Hans George Hansen could be located, and Annie could not win the civil case without producing a marriage certificate. She was dismissed.

Annie left town less than ten days after the Northern Miner suggested that it it would be the best course of action for a baggage like her.

“We think it is high time that Annie Clarke, or Annie Hansen, or the “Canary” should “pipe” down. She has been knocked off her perch as a married woman, and that role is played out. If she continues on the field, she had better sail under bare poles and fly a “pirate” flag without any more D nonsense about it. She has been taking in innocent and confiding storekeepers all round, pretty well smashed up and demoralised one firm, and is laying herself out for fresh captures. In fact the field is too small for her soaring talent. We would recommend her to take flight, or her pinions may be clipped shorter. Cart(h)er out softly her race here is run.” The Northern Miner, 20 October 1875.

“Cart(h)er out softly” referred to Mr Carter, who represented the judgment plaintiff in the civil case.

Mrs Creane

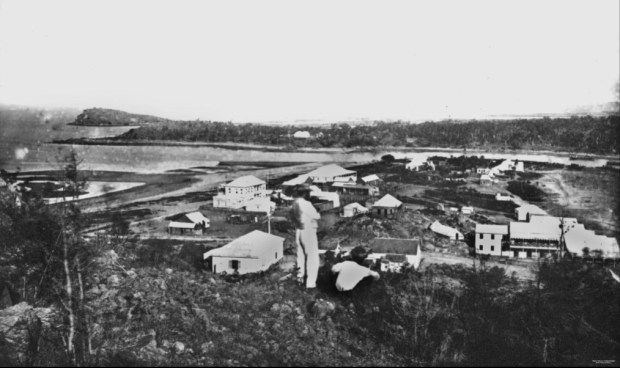

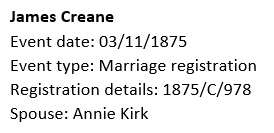

Where had Annie gone? Oh, to Townsville, to get married to a man named James Creane on November 3, 1875. This was while she was still apparently married to the apparently absent or non-existent Hans George Hansen, or George Hansen. James Creane was probably the same person as the James Craine who had gallantly helped Annie from her carriage back in September, when she found her hotel ransacked. Annie entered the marriage register as Annie Kirk, a widow.

Mr Creane was usually a resident of Sydney, and all we know of him is that he had lost an eye around the time of his marriage to Annie, and that he “followed the occupation of a billiard-maker at Major’s.” The marriage was performed just before 8 pm, the cut-off time for legal marriage in the 1870s.

The wedding sounded partly charming and partly raucous. Annie’s little dog came to watch the proceedings at Father Connolly’s Catholic Church, and Father Connolly joked that it was there to see fair play. The raucous part took place at John and Jane Hudson’s hotel in Townsville before and after the ceremony. There had been a fair bit of day-drinking before the wedding, and Creane had caused a ruckus at one point by knocking on the windows to find his bride, who may have been passed out on the cook’s bed at the time. No-one saw Creane with her in the evenings, and no-one knew if the marriage had been consummated. Annie was seen at the steamer terminal with another man shortly afterwards.

Less than three months after her wedding to Creane, Annie Clarke or Kirk found herself before the Rev. Mr Sutton at St John’s Church at Brisbane, going though the Anglican rites of marriage with one Charles Collins, a grazier from Spring’s Creek. The blushing bride gave her name as Maude Elizabeth Henderson.

Mrs Collins

Charles and Annie met in Townsville in January 1876, and, despite warnings from their friends, and his family (especially his family), they headed straight to Brisbane to marry.

A family makes music on the verandah of Spring Creek Station, c.1900

Annie Collins, as she now was, joined her husband at the family station in Spring Creek, where her presence “caused much annoyance to respectable people.” Such annoyance that Mr Ezra Firth, founding father of Mount Surprise and a relative by marriage to Collins, no doubt egged on by the appalled Collins family, swore out a complaint before Fitz-Roy Somerset, one of Her Majesty’s Justices of the Peace for the colony. To be sure he prosecuted the correct person, he named the defendant as Annie Clarke, alias Annie Kirk, alias Annie Anderson alias Maude Elizabeth Henderson.

Everyone was against the marriage in general, and Annie in particular. Everyone except her besotted husband, who approached Ezra Firth to ask him to withdraw the complaint, then asked his wife not come to Townsville for the hearing. He gave evidence that “my brother also asked me if I intended to take you back to the station after this disgrace, and I said ‘yes.’”

For reasons not made public, the bigamy case that made headlines in November 1876 when it was first mentioned, never proceeded. Probably because the Collins family could not bear the scandal and had Mr Firth withdraw the complaint. Annie and Charles decided to make New South Wales their home from then on. They married again, just to be on the safe side.

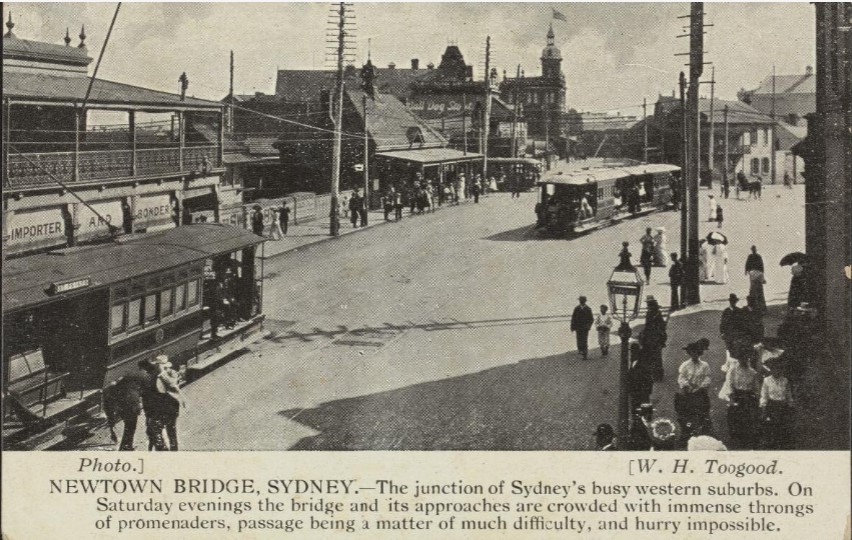

Life in Enfield and Newtown

Charles Collins took a house at Enfield for Annie and lived with her when not on his station in the New England district. Enfield was hardly interesting enough for Annie, even with a generous allowance, so Charles sold up, and moved the marital home to Newtown. He was obliged to spend a lot of time at his station, named “Bolivia” for reasons best known to himself.

Annie remained Annie, and there was quite a bit of drama involving men and money in the remaining decade of her union with Charles.

In 1885, she took a former police officer named George Smith to court to recover a £7 loan, tendering a lot of embarrassingly florid correspondence from the respondent to the court. She was still a wolf among lambs when it came to the opposite sex.

In November 1888, a new man entered Annie’s story. A cabman and former police officer named Caleb Basson was arrested for using threatening language towards Annie Collins. He was bound over to keep the peace. He kept the peace with Annie, but figured in her next two, yes two, divorces.

Divorce from Charles Collins, 1889

Despite her early history of hurtling up the aisle with Mr Right Now, Mr Convenient and Mr Possibly Fictional, Annie had remained married to Charles Collins for twelve years. Or thirteen, depending on which marriage to Charles Collins you counted from. During the hearing of Collins -v- Collins, Lansdowne and Basson, the story of her early marriages became both clearer and more confusing, depending on the husband.

Charles Collins came to Newtown from his Bolivia Station in New England in May 1888, and found Annie cool to him. They slept apart while he was in town. His sister-in-law, Mrs Frederick Collins, lost no opportunity to inform a bewildered Charles of Annie’s behaviour in Newtown and during a visit she paid with Annie to Melbourne three months earlier.

The day before the two women departed for Melbourne in February 1888, Annie had a row with Caleb Basson over money she said she had lent him, and about the trip to Melbourne. That evening Annie Collins retired to bed, and her sister-in-law opened the door to Basson, who went up to Annie’s room, telling the scandalised Mrs Frederick Collins that he intended to stay the night.

The following day, Annie and her sister-in-law were met at the station in Melbourne by a Mr Lansdowne, who appeared rather annoyed at Mrs Frederick Collins’s presence. Annie stayed one night in the room she was supposed to share with the other Mrs Collins at the Royal Arcade Hotel, and then decamped to lodgings in St Kilda, where she styled herself Mrs Lansdowne, and remained until it was time to go back to Sydney.

Attempts by Mrs Frederick Collins to remonstrate with Annie about her behaviour were met with open hostility. On hearing the tale, Mr Collins met with his lawyers.

In the process of explaining to the Court how and when he had married Annie, Charles Collins admitted to marrying her twice – in January 1876 and then in May 1877. The first wedding, he told the court, was conducted before Annie’s decree nisi to her husband was absolute. The second wedding was to make things right and proper.

Annie’s previous husband, James Creane, did not make an appearance in Charles Collins’ testimony. The husband she had failed to divorce in time in 1876 was described as Hans Anderson (Telegraph, Brisbane), Hans Hansen (Sydney Daily Telegraph), and Neil Anderson (Australian Town and Country).

After Charles Collins divorced Annie, she wasted no time marrying a seaman named Charles Peterson in December 1891. How Caleb Basson, her co-respondent in the Collins divorce, initially felt about her new status as a sailor’s wife can only be guessed at. Apparently he didn’t hold a grudge for too long, because they reunited for some more easily detected adultery between May and July 1894, prompting Charles Peterson to obtain a divorce.

Annie appears not to have married again, in New South Wales, at least. And, given the extraordinary number of names at her disposal, she proved impossible to track after the Peterson divorce.

So Many Husbands

Who were Annie’s husbands? How many men was she married to at once? The best guesses I can come up with after weeks of research on all of the names brought up in her cases, I have come up with the following people:-

Mr Anderson

One Hans Anderson married a Mary Ann Kirk in Sydney in 1866. I think that he is the best candidate for the Mr Anderson mentioned in the Collins trial. Mary Ann Kirk was a name that Annie frequently used at the altar and is most likely her real name. Hans Anderson was alive at the time of the subsequent weddings – all of them – but died in 1897.

There is a record in Queensland of Neils Peter Anderson marrying an Annie Anderson on 26 December 1873.

Best candidate: Hans Anderson of Sydney. Although Annie may have bigamously married Neils Anderson in Queensland as well. She was quite entitled to use the surname Anderson after all. She may well have married both.

Mr Hansen

In New South Wales, one Hans Hansen married a Mary Noonan at Albury in 1871. There is no record that this Mrs Hansen left either her husband or Albury for a career in far North Queensland.

There is no record of George Hansen or Hans George Hansen marrying in Sydney circa 1866-1873. (Dr Lang married a Henry Hansen to a Susan Matthews in 1862 in Sydney. Anne must have known about that wedding, because she called up the groom’s name and Dr Lang at her first criminal hearing, but later denied that recollection.)

Three Hans Hansens married in Queensland between 1868 and 1874. Two married Nordic-sounding woman, the third married a lady named Margaret Parsons.

Best candidate: None of the above.

Mr Creane

James Creane or Crane is mentioned briefly (as James Craine) in the Labatt-Ross trial in 1875, for helping Annie down from her carriage when she arrived back at the hotel. No doubt he assisted her flight from Millchester in early November 1875 and was rewarded by her hand in marriage in Townsville.

Annie’s bigamy trial heard that Creane was away a great deal, and the couple were not close even at the time of the wedding. When Creane returned to Townsville to find it scandalised by the Collins marriage, he showed some interest in talking to the wealthy grazier about his new wife, thought better of it, then disappeared from public view.

Mr Collins

Charles Collins was quite a catch for a former hotelkeeper who had led “a very abandoned life” in the goldfields. After her wedding, “she proceeded to the station where she became as it were a wolf among lambs and caused much annoyance to respectable people leading to the present prosecution.”

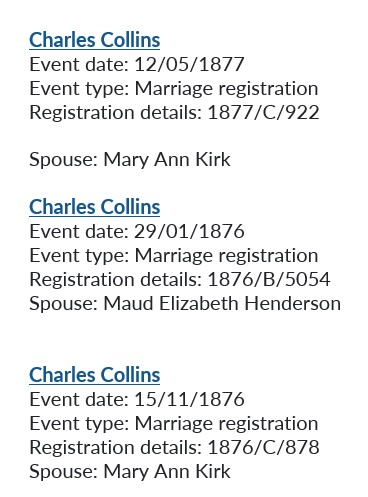

Charles Collins married Annie three times in all. Initially, on 29 January 1876, when she called herself Maud Elizabeth Henderson, then on 15 November 1876, and then finally on 12 May 1877. She called herself Mary Ann Kirk on the final two marriage registers. Charles Collins must have loved her to marry her three times, and under two names.

So nice, he married her thrice. BDM Qld.

The Australian Town and Country article suggested that Collins was about 55, and Annie approaching 40 at the time of their hitching. That would have made Annie in her mid-late 50s at the time of the Smith, Lansdowne and Basson affairs, which seems a little unlikely. I suspect that she was in her late 20s or early 30s in the Millchester period, and she must have been quite attractive, or she would not have been proposed to so much and so often from 1866 to 1894.

Mr Peterson

The decree nisi from Charles Collins must have been made absolute (one hopes) by Christmas Eve 1889, because Annie had found a new man to marry – one Charles August Victor Peterson. Charles Peterson was a seaman and spent a lot of time on voyages. This did not bode well for a man married to Annie Clarke. Caleb Basson came between the Petersons in 1894, and Annie found herself a divorcee again.

Perhaps Mary Ann (Annie) Kirk (Clarke) didn’t like to be alone. Perhaps she felt protected at law and financially by being married. Perhaps she could achieve respectability. Perhaps she just really loved orange blossom. We will never know.

I have included accounts of Annie’s legal adventures in far North Queensland in the accompanying post “The Trials of Annie Clarke.”

2 Comments