Annie Clarke saw a great deal of courtrooms during her colourful career in Northern Queensland. Some extracts from the reports of her hearings at Millchester gathered here show the times she lived in – times when women who had sex with men they were not married to were not entitled to be believed as witnesses. Her character comes through clearly – she was bold as well as crafty with her admissions and omissions. She knew her way around a cross-examination.

By way of background: Annie Clarke moved to the goldfields area of Charters Towers and Millchester in 1874, at the invitation of an older man, Mr W.A. Ross. Ross “kept” her, while she took up the license of the Tattersall’s Hotel as a single woman. The Millchester community, which didn’t have spectacularly high standards of behaviour itself, was uncomfortable with the arrangement being so open.

The break-in case

On Sunday 26 September 1875, Annie Clarke came back to the Tattersall’s Hotel after a night away doing heaven knows what with heaven knows who, and found her living quarters had been broken into, and money and personal items stolen. It appeared that the break-in had occurred early on Sunday morning, and there were quite a few witnesses up and about who could identify the culprits.

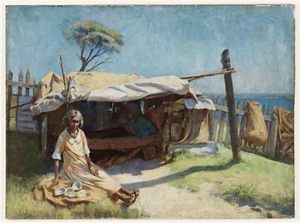

Millchester Road, towards Charters Towers, c. 1890.

Jonathan F. Labatt and William Charles Ross (nephew of the Mr Ross who ‘kept’ Annie) were charged with the offence of breaking into a dwelling in the night with intent to commit a felony and were brought up before the Police Court. They were young men of reasonable reputation about the town and had retained a solicitor named Mr Bowker for their defence.

At the first hearing before the Magistrates, Annie’s identity and marital status seemed to matter more than establishing the facts of an indictable offence. Mr Bowker was planning on using Annie’s morals against her to excuse his client’s behaviour.

She was named Annie Clarke, she said, her surname was her stepfather’s. She was a married woman – “was married in Sydney in the Rev. Dr. Lang’s Church, she thought.” No, she couldn’t remember which exact church it was. She didn’t think she had ever sworn to whom she was married. She had been “in no business” lately, she resided in the Tattersall’s Hotel. She knew a Mr ________ and had been on intimate terms with him.

The Bench gently prodded the case back to the facts surrounding the security of the hotel, and the sequence of events, which hardly interested anyone present, except Annie.

There was still one prosecution witness due to be called, a Mr Scott, but he was found lying in the street with his hat off just before the hearing was due to commence. Case adjourned.

The following day, the identity of Mr _______ was revealed when another case involving Annie came before the Bench. Mr W.A. Ross had been charged with assaulting Constable Waldron earlier that week. Annie had called for the constable during a domestic dispute, and he arrested Mr Ross after a tussle on the verandah. Constable Waldron alleged that Annie had told him that Ross had threatened to burn down the house, but Annie (appearing for the defence) gave evidence that she feared that Mr Ross would burn her clothes. It was Ross’s house – he would not want to burn that down. The assault was proven when she deposed that Ross had pushed Waldron off the verandah.

Trial – October 6, 1875

Millchester was still a small town, and jurors who could be relied upon to be impartial about Annie, the Ross family, or the main witnesses, were hard to find. After a long morning trying to fill the jury box, the Crown Prosecutor opened the case against Jonathan Labatt and William Charles Ross with a series of bombshells. It “appeared,” as he carefully put it, that Annie was married to a man named George Hansen and was the keeper of the Tattersalls Hotel. She was also an immoral woman “a canary,” who was kept by a man named Ross. However, the jury was told to decide on the facts of the break and enter, not on the character of the complainant.

Annie Clarke gave evidence that her establishment had been broken into and her belongings tossed around. £37 was missing. She lived alone. She was married to a man named George Hansen and had “never been divorced by any competent court.” (Clever.) She did not know if her husband was still alive.

A parade of Millchester’s most colourful residents then proceeded to give evidence of their whereabouts and observations between 5 am and 7 am on Sunday morning.

James Scott, an accountant who lived in a humpy, gave evidence that identified both defendants and placed them at the scene of the crime around 5 am. He denied that he had been offered £5 to say so by Annie Clarke, or that he was a drunk. He claimed that his one drink had been tampered with, and that was why he was lying in the street with his hat half off on the last court date.

Mary Ann Budgen, a servant at Murray’s, also gave eyewitness evidence about the identity of the thieves and the time. She also denied being a drunkard, and denied having been bribed by Annie Clarke to give evidence against the defendants. She was now, conveniently, in the employ of Miss Clarke.

Thomas Stannard, publican, gave evidence of seeing the prisoners at his establishment. He was an early riser, apparently serving drinks to customers between 4 and 5 am. These were the gold fields after all, people got thirsty at all hours.

Matthew Murray, publican, gave evidence that Mary Ann Budgen had been very drunk that morning; she was ordered off the streets by Sergeant Beggan. He, however, was never drunk – he was just sometimes the worse for liquor.

Patrick Murray, a servant, recalled seeing Mary Ann Budgen at the same time; she was not drunk, but she looked like she could use a drink, she “looked a bit tore.”

Stanley Wolferston, bailiff, recalled seeing Budgen at 7 in the morning, drunk and with two pieces of bacon in her hand. She had not said anything to him about seeing the accused in the commission of a crime.

Mrs Lavery, Queensland Hotel, gave evidence that Budgen was drunk that morning, and had been purchasing bacon on her behalf, although Budgen was not in her employ. She claimed that Clarke and Budgen had been meddling with witnesses. In cross-examination Mrs Lavery stoutly denied that she herself was a lush, also claiming that her black eye was from her husband hitting her accidentally, not beating her for habitual drunkenness.

William Mathew Mobray, Clerk of Petty Sessions, gave evidence that Annie Clarke had previously sworn in a court hearing that she was married to a Henry (not George, as Annie had stated) Hansen at Newtown Sydney.

John Rutherford, chemist, saw Annie Clarke with a lot of money on Tuesday 28 September, the day after she claimed to have been robbed of a lot of money.

James Pyle, miner, gave evidence that Mary Ann Budgen had been quite sober when they stopped in the street for a neighbourly chat between 5 and 6 am on the day of the offence.

It seemed that most of the town was up and about between 5 and 7 that Sunday morning, encountering each other in various states of inebriation.

The defence went to town in the closing address – “the witness Annie Clarke was a common prostitute, Budgen and Scott notorious drunkards and their evidence was untrustworthy, one of the prisoners Ross was a nephew of W. A. Ross and this woman had ruined him and his nephew; young Ross had tried in vain to break the old man from the wretched connection.”

In reply, the Crown Prosecutor asked the jury whether it was necessary for a victim of a robbery to be a pillar of society. Silly question. Everyone, including the judge, thought that kept women and drinkers ought not to be believed.

His Honour summed up for the jury, leading them through the characters of the prosecution witnesses in particular. He felt it necessary to deliver a moral lesson on what befell women who did not live with their husbands:

“The evidence went to show than the character of Annie Clarke and Budgen, was of such a nature that they were not entitled to be believed. It was an unfortunate thing and a deep disgrace to the community that women should live separated from their husbands with other men, great immorality of that kind had existed here, and it should be put down with a strong arm and men should rise to a proper sense of what they owed to themselves and society. The men did not suffer from those immoral connections, but the women became debased and reduced to absolute wretchedness, lost body and soul for the gratification of the animal passions of men. Annie Clarke, he thought answered very fairly, she admitted being kept as a mistress by one Ross. There was Mrs. Budgen who was always in liquor and never got drunk, then Murray who appeared no better in that respect, and Mary Lavery who explained how she got her black eye in a manner it was for the jury to consider.”

The defendants were found not guilty, unsurprisingly, although the judge told them they had a very close brush with the law. If the complainant and witnesses had been Carmelites, perhaps Ross and Labatt might have spent a long time in gaol.

Civil matters

On 19 October 1875, the Millchester Bench heard an interpleader summons taken out in the name of George Hansen, over goods seized from Annie Clarke after a Small Debts hearing. George Hansen, in the application signed by his wife Annie Hansen, claimed to be the rightful owner of the goods, and sought an order that they not be sold.

The bailiff, Stanley Wolferston, described seizing several boxes of Annie Clarke’s property to satisfy a judgment, and cast an eye over the premises. “It was difficult to say what business Annie Clarke was now carrying on; he supposed a refreshment saloon,” if one could count brandy as a refreshment. Mr Wolferston didn’t seem to. The main part of the premises appeared to Wolferston to be a glorified billiards room, but he observed that Miss Clarke was not living in that room.

Annie’s claim to the goods depended on her marital status. No-one knew a Mr George Hansen, and Annie, ever adaptable, gave a version of her marital history that included marrying one Hans George Hansen about seven years earlier, in Newtown. Besides, she never swore she was married in Sydney – she swore that she thought she was married in Sydney.

As for Hans or George, “I do not know where that darling of a husband is.” She had been separated from him about eighteen months, because she suspected him of bigamy. She was unable to produce a certificate of marriage, and thereby lost the case. She could not show that she was married to the applicant, and to return the goods to her would mean that she was trying to obtain them under false pretences.

Three days later, Annie was convicted of assaulting Jonathan F. Labbatt – one of the defendants in the robbery case from September – and fined £1 plus costs. No doubt she took out her frustrations on the man involved in the case that ruined her relationship with Ross and signaled the end of her stay in Millchester.

By the end of October1875, Annie had left town. She did leave behind one last dust-up. James Pyle, a miner who’d been a witness for Annie in the break-in case, “gave” a gold ring with his initials monogrammed on it, to Annie at an hotel in Millchester. Or, more accurately, Annie “took the ring off his finger.” He next heard of the ring when Annie told him that a local horse dealer named Robert Bedford had the ring, and that Pyle ought to get it back. Pyle had been waiting 4 or 5 months for Annie to have “manners enough” to return it. Meanwhile Miss Clarke skipped town.

Robert Bedford, when approached, refused to give up the ring, because Annie had given it to him as security for the loan of a horse one day, having failed to come up with the £1 requested. He had kept the ring because Annie refused to give him the £1 after the horse threw her. The Bench, no doubt rolling its collective eyes, told Mr Pyle to give Mr Bedford a quid, and Mr Bedford to give Mr Pyle the ring.

The bigamy hearing – 1876

Shortly after leaving Millchester for Townsville, Annie Clarke married a billiard-maker named James Creane or Crane. Within three months of that marriage, she presented at the altar in Brisbane with a grazier named Charles Collins. At the Collins wedding, she called herself Maud Henderson.

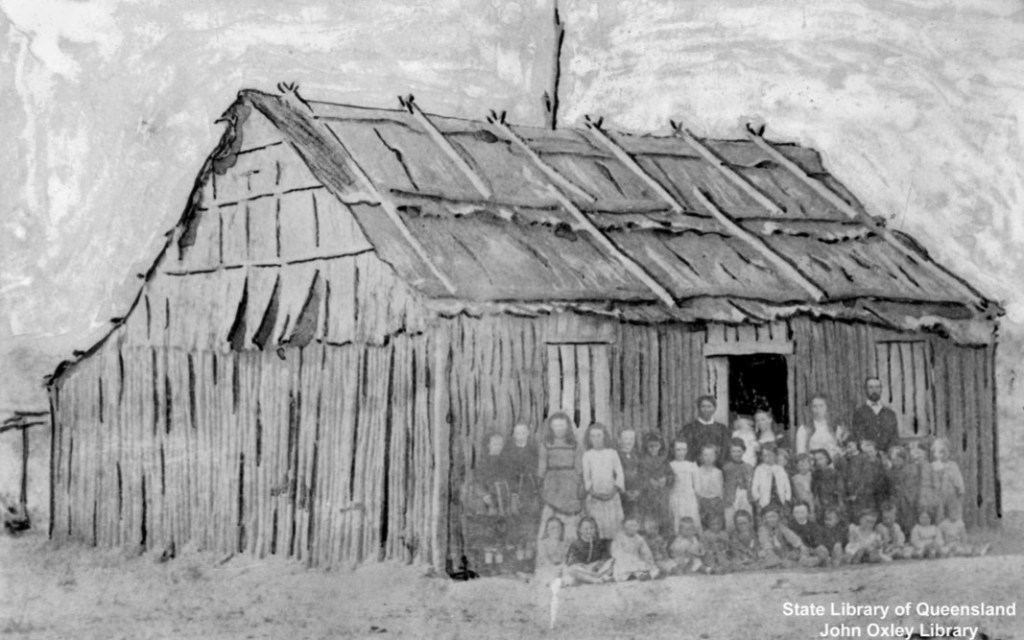

Not the Mount Surprise Station that Ezra Firth owned, but it is the Mount Surprise Station, in a manner of speaking. Ezra Firth founded Mount Surprise as a settlement.

The Collins family, and the community of Spring Creek, did not enjoy having a Woman With A Past in their midst, and this led Ezra Firth, founder of Mount Surprise and a relative of the Collins family by marriage, to take out the following summons:

The information and complaint of Ezra Firth, of Mount Surprise Station, in the colony of Queensland; grazier, and made on oath before me, the undersigned, Fitz-Roy Somerset, one of Her Majesty’s Justices of the Peace acting in and for the said colony, this 15th day of November in the year of our Lord 1876, who saith that Annie Clarke, alias Annie Kirk, alias Annie Anderson, on the 3rd day of November, 1875, at Townsville. in the colony of Queensland, did marry one James Crane, bachelor, and him the said James Crane then and there had for her husband, and the said Annie Clarke, alias Annie Kirk, alias Anderson, alias Annie Crane, afterwards and while she was so married to the said James Crane as aforesaid, to wit, about the 29th January 1876, at Brisbane, in the said colony, feloniously and unlawfully did marry and take for her husband one Charles Collins, and to him the said Charles Collins was then and there married, the said James Crane, her former husband, being then alive, against the form of the statute in such case made and provided, whereupon the said Ezra Firth prays that the said Justice will proceed in the premises according to law.

That’s putting it as confusingly as possible.

A preliminary hearing was conducted, in which various witnesses to the Creane marriage testified to the events of November 1875. Although Annie did not give direct evidence, she was allowed to cross-examine the Crown witnesses.

Mrs Jane Hudson, a witness to the wedding, deposed to a hasty ceremony on the 3rd of November 1875. Annie tried to nudge Mrs Hudson into stating that there had been a lot of drinking that day, and the Creanes saw little of each other.

The Police Magistrate produced the register, and found that a Mr James Creane, bachelor, was married to Annie Kirk, widow on 3rd November 1875 at the Roman Catholic Church at Townsville.

Ezra Firth, a grazier, residing at Mount Surprise, gave evidence that Charles Collins had asked him to withdraw the complaint. Under cross-examination by Annie, he admitted that his daughter was married to Collins’ brother, and that the two ladies did not get along, to put it mildly.

Charles Collins, who had given evidence about his marriage in Brisbane, was cross-examined by Annie, and the results were interesting:

“I did telegraph to you at Bowen not to come, and you did telegraph back to ask what was the matter; you said you would come back. I did say that Firth and my brother Tom Collins were talking with me over this case. I did tell you that Firth in the presence of my brother asked me to come over to Mr Somerset to get the case settled without bringing it into court. Firth said I should get a clearance from you, and the case would not be brought into Court. My brother asked me if I would prosecute, and I said I would not; my brother also asked me if I intended to take you back to the station after this disgrace, and I said “yes.” Firth said he did not wish to injure me in any way; he said nothing about your meddling with his family or scandalising them.”

Charles Collins proved to be a devoted husband, willing to endure the disapproval of his family and community in order to be with Annie. At this point, the case was adjourned for further evidence, and Annie was bailed. It never proceeded from there. Despite the scandalous headlines, when the matter should have gone to trial, the case was simply dismissed without explanation. Annie and Charles had re-married, and were planning a new life in New South Wales. Mr Firth quietly withdrew his complaint in the light of this happy prospect.

Charles and Annie left for Enfield, New South Wales. Annie was given an allowance and installed in a comfortable home. From this happy situation, she could look back on the years spent marrying too often and not well. Because she escaped a bigamy conviction in Townsville didn’t mean that she was not guilty of bigamy. A lot of bigamy. (See “The Marrying Kind.”)

1 Comment