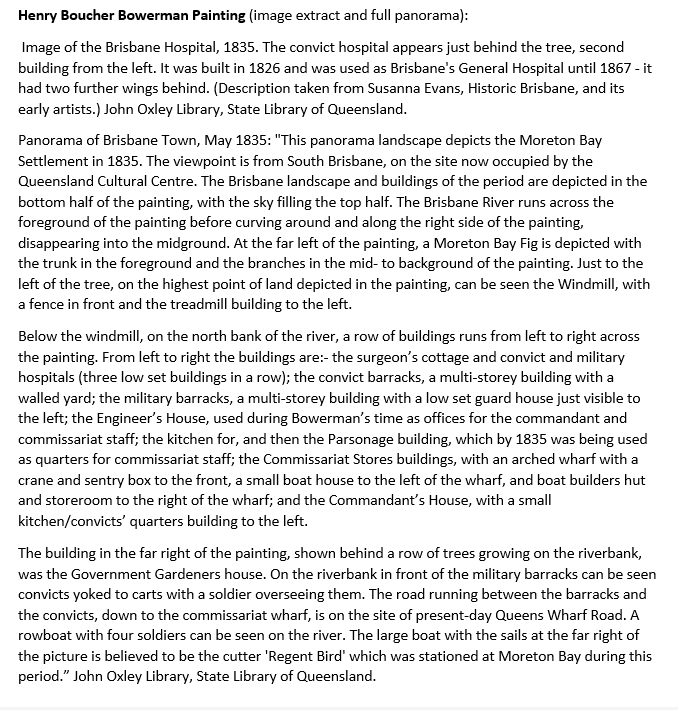

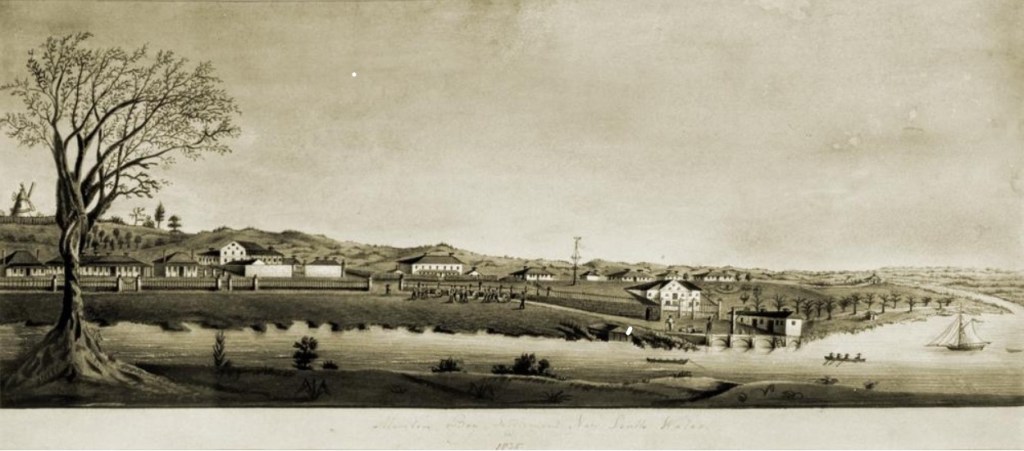

The Convict Hospital

When the Moreton Bay penal colony closed for business in 1842 and became a town, the official records dispersed, mainly to Sydney. Many were lost, some fetched up in unusual places, but a remarkable number of documents survived the ensuing 200 years. The records of the Moreton Bay Hospital have largely survived through the work of the John Oxley Library and the Queensland State Archives.

The situation of the Brisbane Hospital was quite unique. It was established as a treatment facility for repeat offenders and their military masters, some 450 miles from the authorities in Sydney. The nearest European settlement was Port Macquarie, 275 miles to the south. The exclusion zone around Moreton Bay, in place for nearly 20 years, meant that only a handful of civilians passed through there. The only changes were in prisoner numbers and military units.

From 1826 to 1832, Colonial Assistant-Surgeon Dr Henry Cowper attended to all of the patients and out-patients at Moreton Bay, read Divine Service on Sundays, blessed and buried the dead, and made do with inadequate supplies and little assistance.

The convict numbers grew from just under 146 in 1826 to 947 in 1831. Food rations were meagre, particularly under Commandant Logan, and the water supply was drawn from brackish lagoons. Conditions were ideal for outbreaks of disease.

After a devastating dysentery outbreak in 1828-9, Assistant Colonial Surgeon Henry Cowper was sent assistance from Dr Fitzgerald Murray. Murray did not enjoy Cowper’s company one bit.

He is a most uncouth original, an excessive grog-drinker and smoker, and the most ill-tempered and quarrelsome man I ever saw, of which I witnessed repeated proof already though I am not a week at the settlement.

Fitzgerald Murray, letter to Mrs Anna Bunn, 10 May 1830.

Understandable, perhaps, given the conditions Cowper had to put up with.

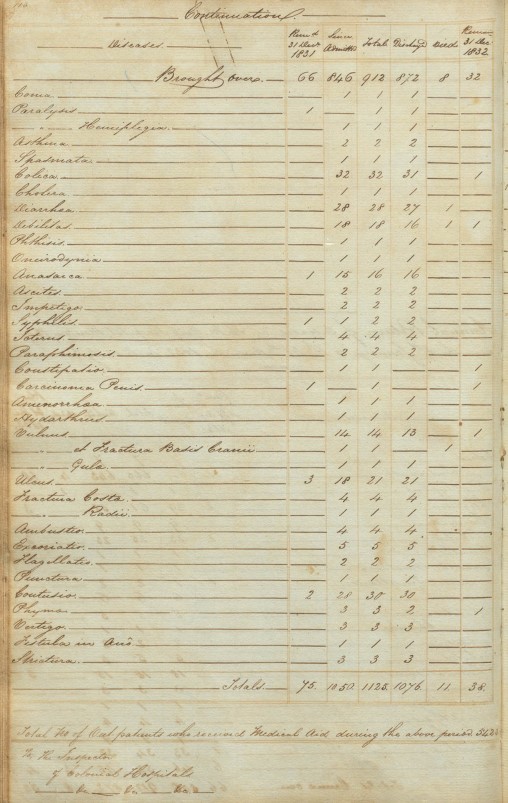

Annual Return of Diseases at Moreton Bay Hospital, 1832.

The patients treated in Moreton Bay Hospital between 1831 and 1833 suffered from three main conditions – intermittent fever, ophthalmia and dysentery. The intermittent fever has been ascribed to malaria, possibly from infected soldiers who’d served in the subcontinent, spread by mosquitos. Dysentery and ophthalmia were more likely a result of poor hygiene and the miserable conditions. Some problems were addressed – rations were increased and flogging was decreased after the death of Commandant Logan in late 1830, but supplies were still largely brought from Sydney, and there were still too many convicts and not enough clean water.

The work of the early medical officers at Moreton Bay, in the days before antibiotics, anesthetic and x-rays, was extraordinary. There were deaths, particularly from dysentery and intermittent fever, but the survival rate was remarkable. Dr Cowper, for all his brusqueness, made careful directions on discharging patients. For example, a teenaged prisoner named John Inman had spent over a month in hospital with intermittent fever, and was noted as “Discharged to have light works in the barn for a fortnight.” Dr Cowper double-underlined it, just to be sure.

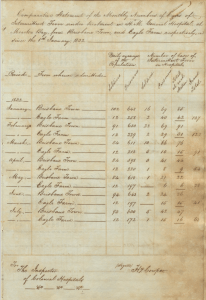

Intermittent fever would remain a problem through to free settlement. Dr Cowper submitted a report to the Inspector of Colonial Hospitals to show how bad the situation had become. The Eagle Farm establishment for female convicts had a particularly bad infection rate, considering its much smaller population.

The Colonial Secretary wrote to Commandant Clunie in 1832:

“The Inspector of Hospitals having represented that the unhealthy situation of Eagle Farm has caused numerous cases of intermittent fever, and suggested that the Establishment should be broken up.

“I have the honour to request your opinion on the subject, and that if you conceive the cultivation of this farm to be injurious to the health of those employed upon it, you will report some other place to which you consider it advisable to remove, specifying the situation selected, the distance from the Settlement, and what Buildings will be required to accommodate the Military and Barracks to be stationed there, and whether the materials of the present Buildings of Eagle Farm can be removed thither, and be rendered available.”

One hopes that Clunie did not expend too much effort in the choosing of the possible new location, because only a few months later, the Colonial Secretary was feeling the urge to pinch pennies:

“His Excellency commands me to renew particularly his desire that No New Building Work be commenced without previous reference to him, and that you will be as sparing of expense as possible even in necessary repairs to those now existing.”

Spending cutbacks grew into a proposal to break up the penal settlement, an idea put into action towards the end of the decade. Prisoner numbers decreased markedly, and the health trends reflected this.

Meanwhile, Dr Cowper had been dismissed from his post for unprofessional conduct, having (with a pal) gotten into the Queen Street Female Factory, and plied some of the prisoners with alcohol. Shenanigans ensued. His Excellency decided to strip Cowper of his post, despite testimonials from Cowper’s friends and colleagues. Historians from Clem Lack to Raphael Cilento have dismissed Cowper’s actions as a sort of undergraduate prank, but to modern eyes, the Governor made the right move. Dr Fitzgerald Murray continued on alone until Dr. Kinnear Robertson took over in 1835.

By 1837, everything had changed. The convict population had been reduced by two-thirds from 1831, and now stood at a more manageable 320. Admissions to the hospital had fallen to just 101 for the whole year. The highest admission rates were for contusions (15), ophthalmia (14) and rheumatism (9). Intermittent fever was down to 2 cases, and there were 3 cases of dysentery.

1838 and 1839 brought a new Colonial Assistant Surgeon, Dr David Ballow, and new illnesses were troubling the shrinking settlement. The entire place seemed to suffer from catarrh and skin irritations, rather than the serious conditions of previous years. In 1840 and 1841, the settlement was in transition. Only the military and a few prisoners employed in the service of the Crown remained. Perhaps coincidentally, or perhaps not, the main illnesses were syphilis (19) and headaches (6).

The convict settlement closed, and health care in Moreton Bay was about to enter a complicated new era.

From the Case Books

Edward Robinson, a soldier aged 32, was admitted on 28 August 1837. “Leg dreadfully lacerated from a log falling on him.” He was discharged on 29 December 1837, only to be readmitted in January. He spent most of 1838 in hospital with ulceration in the wound area, until Dr Ballow thought he needed to be sent to Sydney as an invalid. He remained at Moreton Bay Hospital, however, discharged again on 27 December 1838. A course of antibiotics, had they been available, would have saved the man nearly 18 months in the hospital.

James Scott, aged 37, was admitted on 12 July 1838. “Complains of great pain in the Head from the effects of a blow from an axe given by one of the Natives.” I’ll bet he did. Scott was luckier than Robinson, and only spent a month in hospital.

Mary Dogherty, aged 25, spent two – no doubt miserable – years in the convict hospital, suffering from a fistula. Surgery would have been unlikely, given the lack of anesthetic and the delicate operation that would have been required. She was eventually sent to Sydney to recover as an invalid.

John Norman spent a long time in the convict hospital in 1830-31, suffering from the effects of four blows to his head and face inflicted by Charles McManus, who used a garden hoe to try and kill his fellow inmate. Norman had been at Moreton Bay a mere three days when this occurred, and had not provoked McManus in any way. His injuries were so severe that Dr Cowper didn’t believe that he would survive.

Charles McManus had openly stated his intention to commit an act that would have him sent to Sydney – to the gallows. This, in his mind, was better than languishing at Moreton Bay. Charles McManus got his wish, and Norman, hideously scarred and suffering bouts of paralysis, was sent to the Invalid Asylum in Sydney.

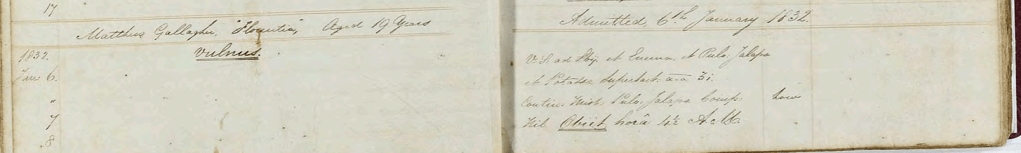

Matthew Gallagher was also attacked by a fellow prisoner wielding a garden hoe. He lasted just two days and died at the age of 19. Patrick McGuire was the attacker, and he too sought a reprieve from Moreton Bay via the gallows. An account of the sentencing read:

“There was, His Honour observed, something so horrid, so entirely at variance with human nature, for a man to deprive his fellow creature of life without the least provocation, and merely (as the prisoner had observed) ‘because he was weary of life,’ that he (the learned Judge) could not comprehend the feeling.”

Next Post: The Health of the Colony: Free Settlement to Separation.