FROM CONVICT HOSPITAL TO GENERAL HOSPITAL

Sick people – please advise

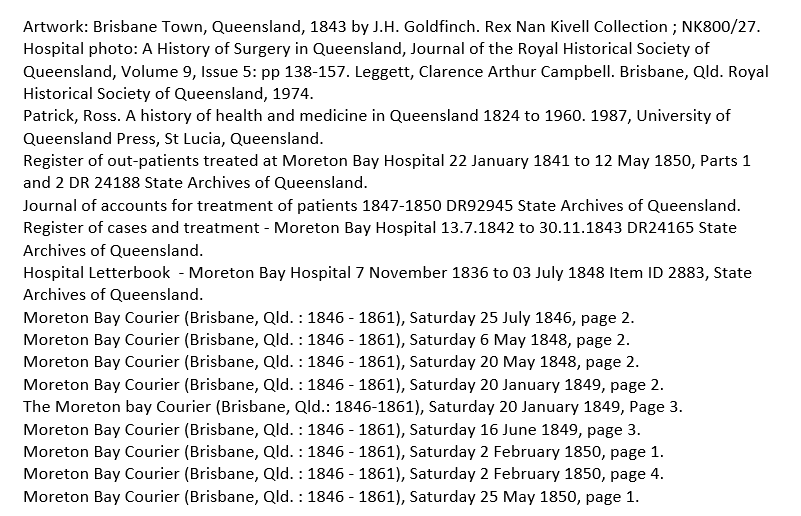

The years 1841and 1842 saw settlers, servants, merchants and labourers moving into or through the township. It seems to have escaped the notice of the Government that these people might need services and infrastructure in order to carve out their existence in Moreton Bay. The Brisbane Town they arrived in was basically Queen and George Streets, which contained some badly-neglected convict settlement buildings and a few private homes.

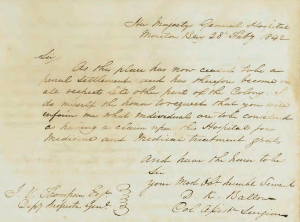

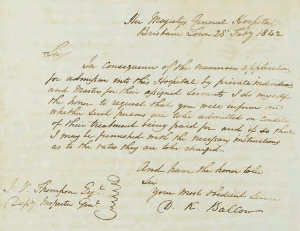

There were still British soldiers in the barracks and a few convicts on bond, and the hospital was theirs to use as required. Initially there were no private doctors, and anyone who needed medical assistance naturally went to Dr Ballow at the hospital. This presented Commandant Owen Gorman and Dr Ballow with such ethical and administrative problems that recourse to the Colonial Secretary, 500 miles away, was sought.

The response was to allow free persons to be admitted on a paying basis, initially three shillings per day, later reduced to one shilling. Cases of accident or severe illness could be admitted, but payment must be extracted. Hospital and outpatient numbers increased with the population.

The arrival of Dr Kearsey Cannan via the Sovereign in 1842 gave Dr Ballow some relief. The 26 year-old set up private practice in the house of Slade, the postmaster, eventually succeeding Dr Ballow in 1850, on the latter’s tragic death.

The use of the hospital became the subject of a decade-long war of incredibly polite attrition between Captain Wickham and Dr Ballow in Brisbane, and the Colonial Secretary in Sydney. The CS was anxious to avoid spending any money on such trifles as public works and health in Brisbane, and Wickham and Ballow were anxious to find a way for the new townsfolk to receive hospital care.

Benevolent Society

The free settlers coming to Moreton Bay were not necessarily well-off. Former convicts, labourers and servants did not earn enough to afford private medical care and the hospital had been instructed to admit free persons on a fee-paying basis.

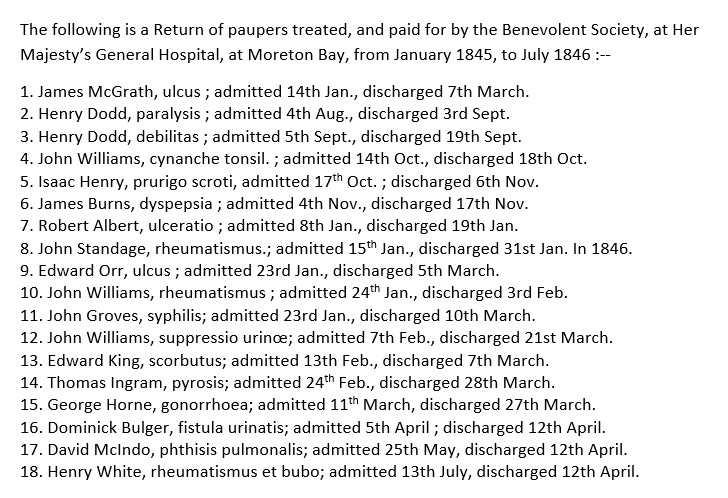

In October1844, a group of public-spirited settlers formed the Moreton Bay Benevolent Society with the purpose of providing relief to “the poor, the distressed and the aged.” The idea of a government providing welfare was unheard-of, meaning that churches and associations were tasked with ensuring that the poor did not die untreated in the streets. Subscription was £1 per annum, and subscribers were not able to access the services of the Society for themselves. They could recommend a person for relief, or contribute generally to community relief.

In return for charitable relief, privacy was lost. The report of the Benevolent Society’s operations in 1845 appeared in the Courier. The patients, their diseases and the length of their treatment sponsored by the Society was laid out for all to see.

The Moreton Bay Courier approved of the charitable work of the Society and its contributors, but felt moved to deplore the spendthrift ways of the lower orders:

“It is the most deplorable feature in the condition of the working classes of this colony that they make no provision, either for themselves or their families, against failure of employment, sickness, or death. The result of such a state of things is, that they have never more than a thin partition between the state of poverty and plenty. When afflicted with disease, many amongst them are quite helpless, and they then are compelled to seek gratuitous medicine as well as medical attendance.”

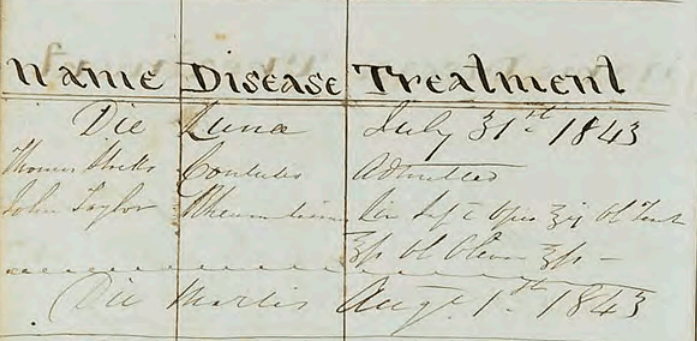

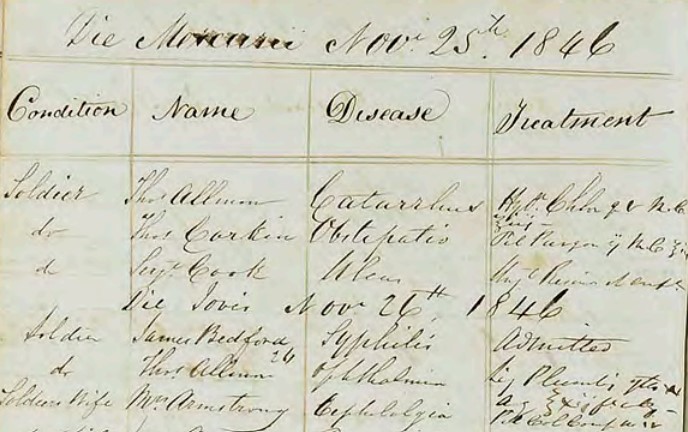

The hospital and the Benevolent Society kept painstaking records to justify how the patients were accepted, but relations with Sydney became strained as the work of the hospital increased, and it became obvious that medicines and facilities provided for convicts and soldiers were being used on free persons and paupers.

Correspondence back and forth to Moreton Bay began to stress the use of the hospital for convicts and the military only, thank you very much. The Admission Books show the change over three years:

Something had to give.

Brisbane Town 1843, showing the convict buildings, including the hospital.

Closure and the emergence of the Moreton Bay General Hospital

As 1848 dawned, the Governor was pleased to inform the Colonial Secretary, who had the honour to inform Captain Wickham and Dr Ballow, that the hospital would close. Its bedding and medicines were to be returned to Sydney, and the building was to be closed.

Our humane and tender-hearted Government sent by the last steamer a peremptory order for the discharge of the patients lying in the General Hospital on the 31st ultimo. They were accordingly turned out of the building to seek refuge in the hour of their distress wherever they could on Monday last. Some of the poor creatures could scarcely crawl, and it was really pitiable to witness their sufferings on the occasion. Had it not been for the kindness and humanity of some of the inhabitants several might have perished in the streets.

The ouster order couldn’t, and didn’t, last. After some swift negotiations per various steamers between the Sydney and Brisbane, permission was granted to allow the townsfolk to create an independent Moreton Bay General Hospital, open to all. Fees were still charged to those who could afford it, and the Benevolent Society merged with the Hospital Committee to oversee patients who couldn’t afford their treatment. The Committee was, however, prepared to accept livestock, produce and furniture etc in lieu of cash payment.

William Wilkes, the Courier’s Windmill Correspondent, was secretary of the Hospital Committee, and set about securing contracts for supplies and services. In advertising for tenders, he provides an insight into the workings of a colonial hospital.

Hospital food has earned a poor reputation, at least in my limited experience, and the horrors the Moreton Bay General Hospital served up can make anyone facing a plate of neon-coloured rubbery jelly grateful for the modern world:

- Full Diet consisted of 1 pound of fresh beef or mutton, 1 pound of bread (first quality), 1 pound of potatoes, 1 ounce of rice, half an ounce of salt, one quarter of an ounce of tea, 1.5 ounces of sugar and a quarter of a pint of milk.

- Half Diet was half a pound of fresh beef or mutton, 1 pound of bread (first quality), half a pound of potatoes, one ounce of rice, one quarter of an ounce of salt, one quarter of an ounce of tea, 1.5 ounces of sugar and a quarter of a pint of milk.

- Spoon Diet was 8 ounces of bread (first quality), one quarter of an ounce of tea, 2.5 ounces of sugar, 2 ounces of rice and a quarter of a pint of milk.

Tenders were sought for the supply of:

“Fresh Beef, Fresh Mutton, Wheat, Bread, 1st quality, Wheat, Bread, 2nd quality, Wheat, Bread, 3rd quality, Maize Meal, Arrowroot, Rice , Sago, Pearl Barley, Tea, Sugar, Salt, Tin Dippers (one gallon), Hair Brooms, Whitewash Brushes, Yellow Soap, Vegetables, Oatmeal, Milk, Bottled Port Wine, Vinegar, Lime, Straw, for bedding, Bottled Porter, Eggs, Rum (W.I.), Fresh Butter, Water Casks, Hoes and Spades.

“All the articles shall be of the best quality of their several kinds; the most rigid adherence to this rule will be observed. The Bread shall be baked twenty-four hours, and no longer, before delivery, unless a special order to the contrary be given. The Vegetables shall be supplied in reasonable proportions of Potatoes, Greens, Pumpkins, Carrots, Turnips, &c., unless a special order from the officer making the requisition shall restrict the supply to one or more descriptions of vegetables.”

Ah, lying on straw matting, consuming mutton and turnips. Enough to make a person recover quickly in order to get out of there.

Mr Wilkes and the committee were also realists. They also tendered for services to pauper patients who did not leave in the pink of health.

TENDERS will be received at the Office of the undersigned, until ten o’clock a.m. of Thursday next, the 21st day of June; from persons willing to undertake the burial of any paupers who may die in the Moreton Bay General Hospital, during the period ending on the 31st of December 1849. All expenses to be included in the Tender. Further particulars may be learned on application to the undersigned. By direction of the Committee, WILLIAM WILKES.

There were stipulations, though:

The graves must not be less than five feet deep, and the bodies must be removed at such times, and under such directions, as may be named by the Surgeons.

The tenders for medicines contained descriptions of the medicines required in Latin, and relied heavily on Quinine, Castor Oil, Iodine, Digitalis, Camphor, Ether, Opium and Morphine.

How anyone survived poverty, illness, hospital food and 19th century medicine is a thing to be wondered at.

Patients

The Case Books for inpatients and outpatients show a significant outbreak of intermittent fever, commencing suddenly at the beginning of 1843, and continuing for the following years. Admissions for febris intermittens were five times higher than the nearest ailment, syphilis. Outpatients presented with febris, but also constipation, rheumatism and syphilis. Hopefully not all at once.

A 30 year old man recently arrived from Sydney, a Thomas Dowse, spent suffered greatly from intermittent fever, and spent a couple of weeks in the hospital recovering. Chief Constable Fitzpatrick suffered a hernia in August 1843, but recovered quickly. Captain Grant was a martyr to dyspepsia, as was D.A.G.C. Kent to impetigo.

Hannah Rigby, a now-famous former convict who had been discharged to Sydney, returned to Brisbane Town when free settlement began, and suffered from debilitas for quite a long time. She shared this condition with Mrs. D.A.G.C. Kent. I doubt that the two ladies had much else in common.

Minor outbreaks of disease were clustered. If one soldier suffered from catarrh, the entire barrack-room was being treated for it by the end of the week. March 22, 1845 saw ten men turn up to the outpatient clinic with diarrhea (considering the population was still very small, that’s an outbreak).

The Moreton Bay General Hospital was up and running, and ready for the 1850s, a decade that would bring a surge in population, and the eventual separation from New South Wales. The hospital began to battle outbreaks of typhoid, tuberculosis, and a problem new to Moreton Bay – old age and debility.