It started out as a bank hold-up in a small western Queensland town. There was a shot fired, and an injury sustained. The robber’s getaway attempt descended into farce as a racehorse and a sheepdog became involved in a chase that ended up with the fugitive surrendering in a tree. In just two months, the law took its course, and the hold-up man was controversially hanged in Brisbane Gaol.

A stick-up on a summer morning

At 10 am on 16 January 1880, a young man named Joseph Wells rode into Cunnamulla on a fine black horse, entered the Queensland National Bank, pointed a loaded revolver at the manager, and demanded the contents of the safe. Mr Berry, the manager, politely refused. Wells had to repeat the request twice, bringing his weapon closer to the manager before the cash drawer was opened.

A Mrs Glanville happened to overhear Wells’ stick-up demand, and raised the alarm with a neighbouring shopkeeper, Mr Murphy of Murphy and Warner’s bonded store. Mr Murphy decided to intervene personally and caught Wells as he was leaving with nearly £200. Murphy and Wells fought, and in the process, Wells’ gun discharged, with a single shot glancing off Murphy’s head and entering his shoulder.

Warner’s Bonded Store (formerly Murphy and Warner), c. 1890 (SLQ)

Wells ran for his magnificent black horse, which took fright and was “sailing majestically around the people with dilated nostrils and head and tail high up in the air,”[1] and galloped off without him. The bank robber decamped on foot, followed by an assortment of townspeople, two of whom had unloaded guns. The robber threatened to shoot his pursuers, which had the desired effect on the amateur posse.

Sergeant Byrne and his constables were now in pursuit of Wells. A local gentleman named Herbert Gwynne, who happened to be passing on his racehorse, Vanity, offered its services to a grateful Sergeant Byrne.

The chase was on, and an excited sheepdog joined in, following Wells’ tracks. The barking attracted the police, who found Wells hiding in a tree with a dog yelping furiously on the ground below. A brief stand-off ended with Wells, complaining that he would rather be shot than hanged, surrendering.

On the ride back into town, Wells “assumed a somewhat jaunty and important air,”[2] which no doubt subsided as he spent the night in the local lock-up, waiting for his first court appearance.

Cunnamulla Courthouse, the scene of Wells’ first appearance. (SLQ)

Mr Murphy, who had been shot in the robbery, received medical attention in Charleville and Brisbane, and made a full recovery.

The trial and aftermath

A month later, Joseph Wells was tried at the criminal sittings of the Circuit Court at Toowoomba. He pleaded not guilty and was not represented by counsel. The Crown had counsel, as did the Queensland National Bank, which had a keen interest in prosecuting someone who had tried to relieve it of a lot of money. The witnesses for the prosecution filed in, giving damning eyewitness evidence. Wells clearly had little idea of how to conduct his defence and was only able to offer up the accidental discharge of his revolver by way of exculpation. He was very quickly found guilty and sentenced to death.[3]

The month between Wells’ conviction and execution saw public agitation at the severity of the sentence and the conduct of the trial. Letters for and against flew in to the Editors of various newspapers, and a plea for clemency was made to the Executive Council and rejected.

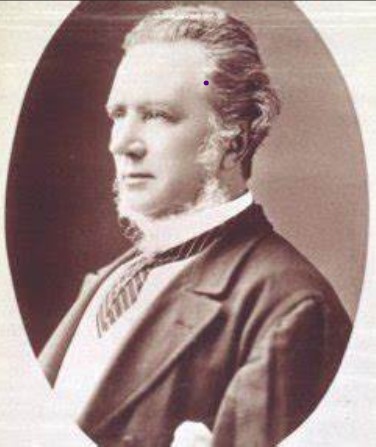

Dr Kevin O’Doherty, a prominent Queenslander with a storied career in Irish nationalism, medicine, and politics, had been a medical witness in the Wells trial and had been an impartial observer for the rest of the trial. What he observed horrified him.

Wells, the good doctor felt, was a young man of limited intelligence, who had no understanding of the plea he had entered, or the consequences of his trial. Dr O’Doherty noticed two of Queensland’s best legal minds, Frederick Swanwick and Charles Chubb, sitting in the courtroom with nothing to do. Dr O’Doherty approached the men, who said that they would have willingly undertaken Wells’ defence, even pro bono, but they felt it was “not their duty to volunteer.” [4]

Then there was the matter of the statute under which Wells had been charged and condemned. It had never been tested in court before and was “badly worded and a disgrace to the statute book.”[5] O’Doherty canvassed the Brisbane legal community, and almost to a man (we’re in 1880 here, there were no women), they felt that the Act was so faulty that a writ of error should be brought to overturn the conviction and sentence.

Dr O’Doherty called a public meeting at Brisbane Town Hall to urge the Governor to reconsider and intervene in Wells’ case. A who’s who of old Brisbane attended in support, including Arthur Rutledge, James Francis Garrick MLA, Frederick Swanwick, Charles Chubb, Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior, the Hon. Dudley Oliphant Murray and William Brookes.

The meeting was full of 1880s opinions. No-one was willing to advocate an end to capital punishment. Mr Rutledge expressed his bewilderment that a ‘common blackfellow’ could be assigned counsel by the Government, but a white man with no money was left to fend for himself. Those assembled carried the motion that a deputation of gentlemen should call on His Excellency immediately, and appeal to him to intervene on behalf of the condemned man. A group of hansom cabs had been stationed outside for the convenience of those gentlemen who wished to visit Government House.

The Governor, Sir Arthur Kennedy, received the deputation with grace and listened to the impassioned pleas of Dr O’Doherty and Mr Brookes with great consideration. And then promptly told them where to go. Not in those terms of course – Sir Arthur was a career colonial administrator and knew how to dismiss people with suitable grace and tact.

“His Excellency said they must be perfectly aware that he could not with any degree of propriety discuss the matter with them. He differed very widely from both the gentlemen who had addressed him. He had thought deeply over this matter, and he hoped and believed that he had as strong feelings of humanity as any one of them. He had exercised those feelings all his life in whatever position he had been placed and had never been found fault with on that score. But he did not think he should be called upon to exercise his feelings of humanity irrespective of his reason; it would be highly improper and unconstitutional to do so.”[6]

With direct intervention out of the question, the petitioners put an application to the Chief Justice in chambers and Wells’ execution was postponed until the case could be heard. The application was unsuccessful, and Joseph Wells went to the gallows on Monday 22 March 1880.[7]

After Wells’ death, some of his antecedents were reported. He had a criminal record, and was a horse-breaker, and probably, a horse-stealer. [8] How much of the tale is accurate is open to question, but it remains the only contemporary account of a man who died very young and, unlike the rich and powerful, did not have much of his life recorded.

[1] Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld. : 1858 – 1880), Monday 26 January 1880, page 3.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld. : 1858 – 1880), Wednesday 18 February 1880, page 3.

[4] Week (Brisbane, Qld. : 1876 – 1934), Saturday 20 March 1880, page 9.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Joseph Wells was not the only man condemned to hang for a robbery with violence that did not result in death. The other bushranger executed for this type of offence was William Brown or Bertram, who was convicted of robbery under arms in 1870 and hanged at Toowoomba Gaol. Brown, living under an alias, was a German immigrant with a long criminal history, and was aged only 20 when he robbed Baker’s Hotel at Mangalor in December 1869. He discharged his weapon in the course of the robbery, injuring William Baker, who made a full recovery. While awaiting execution, Brown boasted to his captors that his friends and family would never know that he had been hanged, because he was not known to them as Brown or Bertram.

[8] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Thursday 25 March 1880, page 3