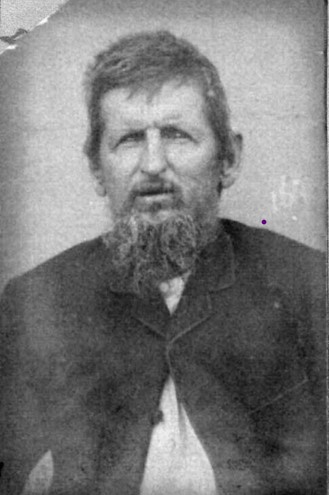

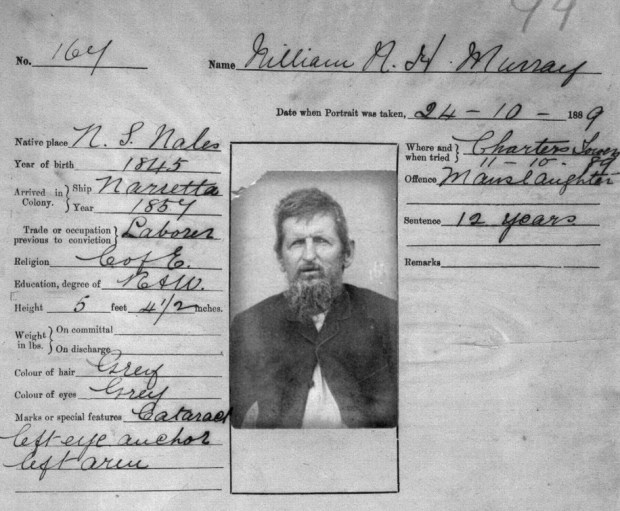

An unkempt and hopeless-looking man stares warily at the Brisbane Gaol photographer. His jacket doesn’t quite fit, and his hair and beard seem to have been barbered using a kitchen knife. His eyes, set deep under faded brows, are pale. His mouth is slightly open, as if the photographer caught him just as he was about to speak.

A look at the Record Sheet shows that this man is William N.H. Murray, aged 44. He looks much older. He had been convicted of manslaughter earlier that month – October 1889 – at Charters Towers.

How did this man end up taking another man’s life?

No-one Here Knew Him

William Nicholas Hollis Murray was born in New South Wales in 1844, and moved to Queensland with his family at the age of 13. He worked in the country as an itinerant labourer, travelling between stations on shanks’ pony or on whatever nag he could afford.

In March 1870, Murray was walking to a station near Theodore, hoping for some work, when a miraculous vision appeared before him. A fine chestnut horse, complete with saddle, bridle and swag, but no rider, galloped into view. Thanking his lucky stars, Murray saddled up and returned to Camboon, where he had been doing some work for the local publican at Arthur’s Telegraph Hotel.

Not far away, a bushman named Christophe Taffe had parted company with his chestnut horse rather abruptly when he tried to avoid a branch that the beast seemed determined to gallop into. Picking himself off the ground, he saw his horse, saddle and swag heading into the bush at high speed.

To Murray’s credit, he told Mr Arthur that he had found the horse on the road, and if anyone enquired after it, they could have it. The contents of the swag were another matter. There was a coat and a pair of trousers, which Murray promptly donned. He was still in the purloined strides when Constable O’Leary from the Banana Police dropped by to ask some questions.

“Well, I’m beggard, that’s good,” remarked Murray when the proposed charges were read out to him. Murray, at the time around 26 years old, received two years’ hard labour in Brisbane Gaol. His replies to the Judge about his antecedents paint a picture of a solitary, hard life.

“In answer to his Honour’s enquiries, prisoner said no one here knew him; he had been 16 years in Queensland in the bush, eight or nine years on the Burnett, also on the Burdekin, and on the Peak Downs. The police knew nothing about him.”

After prison, Murray returned to the wallaby track. He married one Caroline Horan when he was 38 – rather a late age for a first marriage in the 1880s, but at least he had a companion in life. Until 1889.

On the Wallaby Track, by Frederick McCubbin (NSW State Government)

“You old B., you needn’t think you’re going to have her anymore.”

May 1889 saw William Murray, his wife and a travelling companion on the dirt road towards Mackinlay, in the far north-west of Queensland. Mr Murray was piloting a dray with a miserable old horse. Mrs Murray had chosen to join their travelling companion, Daniel Roberts, in his spring cart, which boasted two horses. Roberts, who also went by the surname Rogers, was a tall man for that time– nearly six feet – and powerfully built[i]. He had a huge jar of overproof rum in his cart, and often partook in a nobbler or two with Caroline Murray.

Charles Johnson, another labouring man, was on the road looking for work, when William Murray kindly pulled up and told him to put his swag in the dray – he could have a lift into town with him. Johnson remembered Murray as a quiet fellow, who was clearly suffering the effects of a fever, and whose eyes were badly irritated by the blight.

By the time the travelers got into Mackinlay, it was getting dark. They stopped at the local hotel for refreshments, then set up camp a few hundred yards away. (Unfortunately for those inclined to the picturesque, this was not the hotel for which Mackinlay became famous – Crocodile Dundee’s Walkabout Creek Hotel – that watering hole wasn’t erected until 1900.) Charles Johnson remained at the hotel for a while, and when he returned to the camp, he heard William Murray and Daniel Roberts having words.

Johnson heard Roberts say, “Murray, I give you half the money and half the rations,” before driving away in the spring cart with Mrs Murray, in the direction of Eulolo Station. Another witness heard Roberts taunt Murray with, “You old B., you needn’t think you’re going to have her anymore.”

William Murray, having been decisively rejected by his wife, went over to another camper, Walter Tucker, and asked if he had a revolver, saddle and bridle. Tucker did not have a gun, but Murray could borrow his bridle – he could not supply him with a saddle. Sorry, mate.

Murray went back to the hotel, and had a yarn with the publican, Albert George Rice. By pretending to Rice that he and his mate were to have a shooting contest, Murray secured the loan of a revolver and some ammunition. Rice would later tell the Court that he did check to see if Murray was either mad or drunk but gave over the gun as the man seemed to be clear-headed enough.

On Murray’s return to the camp, he told Charles Johnson, “If I fall tonight the horse and cart belong to you.” Johnson asked what Murray meant, and Murray said he would “stop them or bring them back.” Murray then caught his tired old horse, bridled it, and rode off into the night with no saddle and Rice’s loaded revolver.

“I have shot a man.”

A man named Daniel Rogers was shot through the brain yesterday by William Murray, at Eulolo Station, and killed. Murray has surrendered himself to Mr. Higginson, the manager of Eulolo.[ii]

Sheep being mustered for shearing at Eulolo Station (undated).

The following afternoon, Charles Thompson, a labourer at Eulolo Station, was taking his tea when a sickly-looking middle-aged man approached him and asked what the place was. When informed that it was Eulolo Station, the man told Thompson bluntly, “I have shot a man, and you had better see about burying him.”

Thompson followed the general directions Murray had given him, and located the spring cart, Mrs Murray (alive), and the body of Daniel Roberts, which was lying half on a mattress on the ground and covered by a red blanket. Roberts had suffered a gunshot to the head.

Mr Higginson, manager of Eulolo Station, received Murray in his office, and asked him what was going on. Murray said, “I have shot a man and suppose I shall have to suffer for it, take charge of me.”

Higginson observed that Murray was “as nearly mad as a man could be, he had been wandering all day without water, had thrown his boots away, and was altogether in a disordered state.”

Higginson put Murray into a locked room and went with Thompson to see about the body. He knew Daniel Roberts well by sight – the dead man had worked around the stations for a few years. Roberts had been a big, strapping powerful man, much taller and stronger than Murray. The men found a spot to bury Roberts, and took charge of Mrs Murray, who was incoherent with shock, as well as the effects of drinking overproof rum and having had no water for 24 hours.

When Higginson was taking Murray into Mackinlay, he asked the prisoner what had happened. Murray said that he knew things were “going crooked” between Roberts and his wife, and that he had tried to part ways with Roberts, the man had refused to leave Mrs Murray. There had been a struggle, and the gun went off. Murray said something about Roberts having been concerned in a murder, but Higginson knew nothing further about that.

Charters Towers Courthouse, 1888 – the year before Murray was tried there. (State Library of Queensland)

William Murray was charged with Roberts’ murder and tried in Charters Towers in October 1889. The jury rejected the murder charge, finding Murray guilty of manslaughter under extreme provocation. The judge sentenced Murray to twelve years in gaol, most of which he spent at St Helena Island in Moreton Bay.

William Murray’s Charge Sheet and Photo, 1889

[i] Daniel Roberts may be the man described in a Victoria Police Gazette as “a colonial native, miner and splitter, nearly 6 feet high, flash manner.” The height and approximate age seem right. Roberts was aged around 41 on his cemetery headstone at Mackinlay. (Victoria, Australia Police Gazettes, 1864-1924. June 1, 1869.)

[ii] Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1878 – 1954), Thursday 16 May 1889, page 5.