Domestic and family violence in the 19th century was tried and punished in a society that took a dim view of wives leaving their husbands, and of children who misbehaved. Divorce was only an option for the well-to-do, and women were seen as the property of their husbands.

There were no dedicated laws preventing stalking and harassment. If a woman attended court and gave evidence against her husband, she faced the possibility that he would not be found guilty. This would free her husband to return home and inflict more violence. If he was imprisoned, she would be forced to keep herself and her children for months or years, and there was the unappealing prospect of her husband’s return. Many women failed to appear and prosecute the cases, perhaps reasoning that it was easier just to let the matter go.

**TRIGGER WARNING: The following stories, particularly the first, contain descriptions of violent acts on women and children.**

“The child had received more than an ordinary beating for a child.”

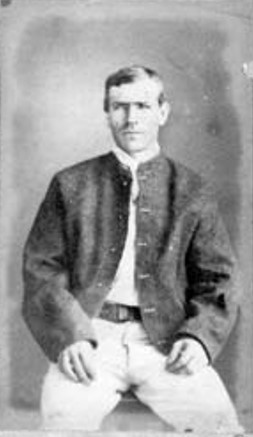

Dr John Scharffenberg.

James David Robinson was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for beating his two-year-old daughter at Millchester, near Charters Towers on 22 September 1875.

On the 22nd, the attention of neighbours was drawn to the sound of a woman screaming. William Bray came out of his house and saw James Robinson use a stick to “thrash his wife… to the hut,” and then turn his attention to his daughter, beating her with a stick as thick as the back of a chair and about a yard long. After receiving 20 or 30 blows, the little girl picked herself up and went inside the hut.

Dr Scharffenberg, called in by the police to examine the girl, found her back, chest and legs “covered with discoloured streaks of blue-brown and blackish appearance.”

Every witness examined stated that the amount of punishment was much more than a parent should give a child. Just what level of violence they felt would be appropriate is not recorded.

“Mrs Robinson, wife of James David Robinson, sentenced last week to six months in Rockhampton gaol for beating his female child, has called on us to state that the case was not so bad as represented. Cela va sans dire (it goes without saying). Only one side was heard. She did not appear the first day at the court, because Mr Bowker told her it was not necessary. She has called our attention to one or two printers’ errors. Dr Scharffenberg swore that the child was not feverish, and Robinson did not “chase” the child with a stick – it should have been “thrashed.” The Northern Miner, 2 October 1875.

“Mrs McMahon, here’s your husband.”

Ellen Walker.

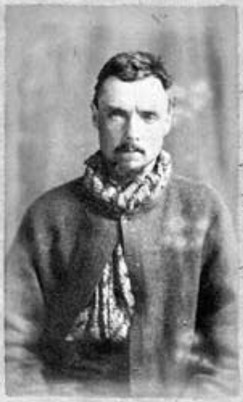

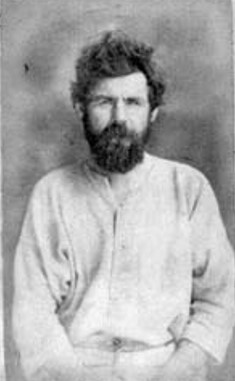

Patrick McMahon looks very sorry for himself in his prison photo. He is starting a 7-year term of imprisonment for unlawful wounding, his second conviction for this offence in two years.

His relationship with his estranged wife was at the heart of both cases. Mr McMahon liked a drink, to put it mildly, and Mrs McMahon left him, taking their children with her. She began a new relationship with John Cunningham, and they lived together in his house in George Street, Brisbane. This was 1875, and her behaviour was considered to be extremely scandalous.

The first unlawful wounding charge Patrick faced was in August 1875, when he entered John Cunningham’s house and stabbed the man in the neck. Mr Cunningham was lying on his bed with Bridget McMahon at the time of the attack, and the judge felt that her misconduct was such that Patrick McMahon should only receive three days’ imprisonment for the attack.

On 28 November 1875, Patrick was drunk again, and visited the house in George Street again. On this occasion, Bridget McMahon was entertaining guests in her sitting room – a solicitor named Robert Rankin Boag (who had defended Patrick previously), and a neighbour named Mrs Walker. John Cunningham was in another room.

Patrick McMahon had again armed himself with a knife, and told a passer-by, Edward Brennan, he would “commit a mutiny.” Brennan went for the police to have McMahon arrested for carrying a knife openly in public. McMahon entered the George Street house and headed straight to his estranged wife, stabbing her in the chest in full view of her horrified guests. He then attacked Boag with the knife, hitting him on the temple, saying “And you too, you _______.” Mrs Walker heard McMahon say of Bridget, “that she was his lawful wife, and had no business to pick up with a cobbler like Cunningham who could not maintain her.” McMahon was a blacksmith, a presumably more lucrative trade.

Bridget McMahon was severely wounded, and her evidence had to be taken from the hospital. Initially, it was thought that she would die.

At his trial in February 1876, McMahon was found guilty and given the seven-year sentence. His actions ruined his family. His children, Bridget and Michael, were admitted to the orphanage two months later, and his estranged wife died in November that year.

Peter McLaughlin was charged with assault, and it related to an attack on his wife in George Street, but the charge proceeded with was assaulting Constable White, who had been trying to stop him beating his wife.

On Tuesday December 7, 1875, Mrs McLaughlin was speaking to Constable White in George Street, about her husband beating her. Peter McLaughlin saw a crowd gathering, and his wife speaking to a policeman, and intervened, kicking her “with great violence.” He then turned his attention to Constable White, biting and kicking him. It took two officers to bring McLaughlin to the watch-house.

The following morning, Mrs McLaughlin did not attend court to prosecute her husband for the beatings. He was fined £5 or two months’ imprisonment with hard labour for assaulting the police. He took the gaol time.

In January 1876, William May was charged with a serious assault on his wife, but she also did not attend court to prosecute. When the matter was finally dealt with, May was given seven days’ imprisonment. Presumably Mrs May had not conducted herself as a Victorian wife should.