Oh, what a night!

Police uniforms certainly took a beating in the 1870s. They looked sturdy enough. Heavy-looking tunics, trousers and forage caps were the order of the day. Yet at least four of the men featured in this post managed to “destroy” a police uniform in the course of their arrests. Restitution was always awarded – heavy, uncomfortable police clothing didn’t grow on trees.

This post looks at the nights to forget – where alcohol (usually) and a bad attitude landed offenders in the Brisbane Gaol.

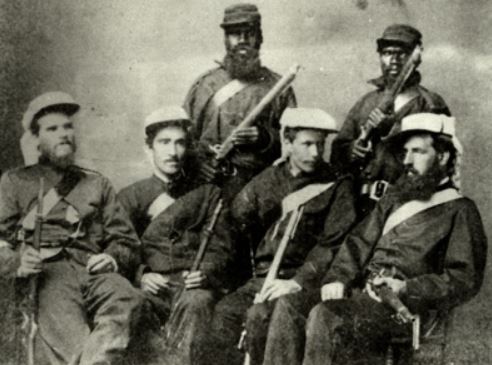

The Gold Escort – showing the uniforms of the era in detail.

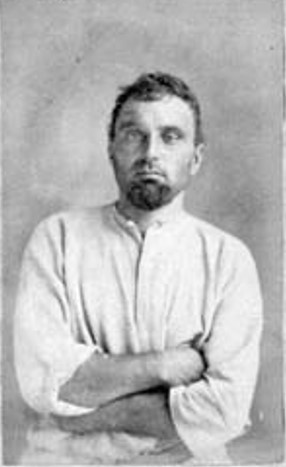

Joseph Hirst was a young labourer, newly arrived from England on the Gauntlet, and frankly not enjoying his time at the Immigration Depot. He was engaged in a fight there on a balmy February night, and Constable Smith was sent to remove him. Hirst didn’t take kindly to this, abusing and assaulting the constable, and “destroying his uniform.” He was sentenced to one month in Brisbane Gaol. In his entrance photo, he is clearly showing the results of his night of fisticuffs.

That same night, John Crawford, also a new arrival by the Gauntlet, was giving full vent to his feelings in George Street, Brisbane. Constable Fleming decided that the elegant atmosphere of Brisbane Town was being tainted by his language, and arrested him. Mr Crawford resisted arrest quite manfully and received fourteen days’ hard labour. His prison photo also shows a man somewhat the worse for his experiences with the law.

The immigrants per the Gauntlet were certainly having a torrid time in the colonies. Edward Roberts tried to intervene in John Crawford’s arrest, and attacked Constable Fleming in the process. He also received fourteen days’ hard labour. Here he is, looking slightly injured and deeply unimpressed.

Patrick Barry was a cook and steward on the Mary Peverly, and in March 1875, he went on a bender and assaulted just about everyone he encountered. The captain of the schooner gave him in charge to the police for being drunk, disorderly and assaulting the mate. Barry added violently assaulting police and destroying a police uniform to his rap sheet and spent 12 weeks performing hard labour at Brisbane Gaol.

In Maryborough, Henry Goodgame was a “notorious character,” and proved it in April 1875 by being charged with using obscene language, resisting and assaulting police and destroying a constable’s uniform. He was given three months to consider his uniform-destroying ways.

Charles Loder hailed from St John, New Brunswick and worked as a miner in the Maryborough region. In January 1876, Loder got very drunk and created a ruckus in McGill’s hairdressing salon. McGill tried to remove this drunken nuisance from his premises and was assaulted by said nuisance. Loder chose to serve the two months’ imprisonment rather than pay the £5 fine inflicted by the Bench.

John Keefe spent September 1875 in Brisbane Gaol after misbehaving in Albert Street (Frog’s Hollow) and punching a John Page in the face.

John McConnell, much like Patrick Barry, became very drunk on board the ship Harmodius, and then fought every person he saw. Literally. He started by incurring the wrath of the captain by being drunk and disorderly, then punched a fellow sailor (Thomas Lanargan) whilst Lanargan was asleep. Then, on being brought to the lock-up, he assaulted William Minogue, the watch-house keeper. Once subdued and placed in a cell, he assaulted a fellow-inmate, Donald Cameron by “striking him violently on the head.” The assaults on Lanargan and Cameron earned him one month each – to be served cumulatively. Here he is, a week after the violent spree, dishevelled and remorseful.

John Meeson (or, as the newspapers reported it, James Muson or Mason) was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for using obscene language in Cooktown, and a further three months for assault, to be served cumulatively. Regrettably, there are no reports of what he said or did, but it must have been quite flagrant to warrant such heavy terms. He was meant to serve them in Rockhampton Gaol but found himself in Brisbane Gaol instead. Hence, possibly, his surly expression.