The Proserpine was converted from a cattle ship to a prison hulk in 1863, and was repurposed again in 1871 to “to receive boys of the criminal class.”[i] The criminal class included children who had been brought before the Bench as neglected.

Neglected children are held, by the sixth clause of the Act, to mean those found begging in any street or public place; the homeless, without visible means of subsistence; children residing in any brothel, or known to associate with thieves, prostitutes, or drunkards; those who, having committed a punishable offence, might, in the opinion of the justices, be sufficiently dealt with by sending them to an industrial school; those whose parents might wish to have sent to such an establishment, undertaking to pay for their maintenance; any juvenile inmate of a benevolent asylum, supported wholly or in part by public or private charity; and lastly, “any child born of an aboriginal or half- caste mother.”[ii]

One little boy who was brought on board in June 1873 as a neglected child was William Henry Cleave, a fair-haired child of 10 years, weighing 49 pounds, and standing just four feet tall.

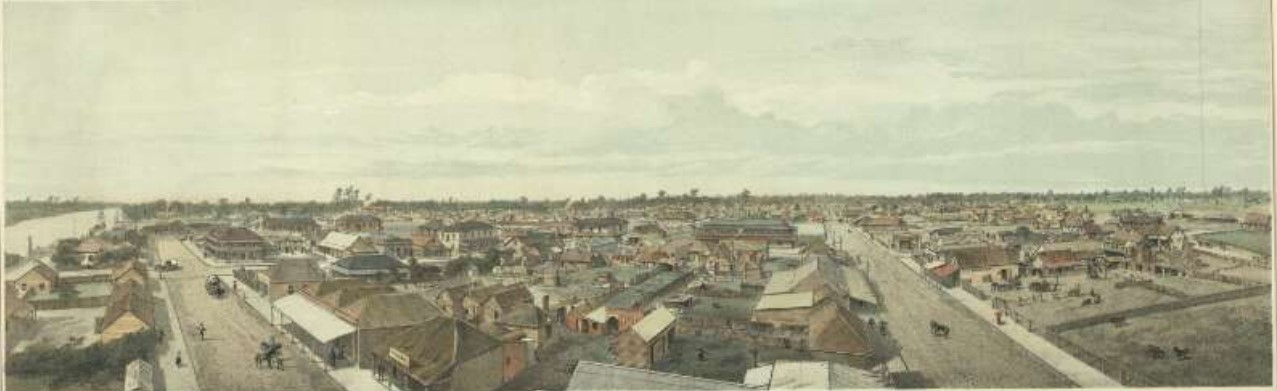

His family had started life in Queensland with so much hope. William had arrived in Brisbane, aged one, aboard the Queen of the South with his parents John and Charlotte. The family moved to Warwick, where brothers John (1867) and James (1869) were born. Charlotte was expecting her fourth child when her husband passed away on 28 July 1871. John Cleave’s death set off a terrible chain of events for the family.

Within two months, William and John were admitted to the Diamantina Orphanage at Brisbane, whose records noted rather coldly, “Father dead. Mother of weak mind.” Charlotte Cleave kept little James at home until after the baby – a little girl also named Charlotte – was born.

In May 1872, James and baby Charlotte joined their older brothers in the Orphanage. The register stated this time, a little more charitably, “Father dead. Mother unable to support them.” The new mother, recently widowed, clearly found getting work and parenting beyond her abilities at the time.

Life went from bad to hellish for the children when three-year-old James died at the Orphanage in July 1872, barely three months after admission.

The following year, 1873, saw William sent to the Proserpine for three years as a neglected child, meaning he was away when baby Charlotte died at the Orphanage on 11 December. On 22 December 1873, Charlotte Cleave reclaimed the one child left at Diamantina, ten-year-old John. After this, understandably, she kept him away from charitable institutions designed to help struggling families.

William spent eighteen months on board the Proserpine, during which time he grew several inches and gained a healthy amount of weight. His behaviour was noted in his record as “very good.” The Executive Council remitted his sentence and released him back to the Orphanage on 22 December 1874. He was the only Cleave child left there. The following month, William was released from the Orphanage into the service of Mr Downman on the Logan and set about advertising for news of his brother John, from whom he had been separated for many years. [iii]

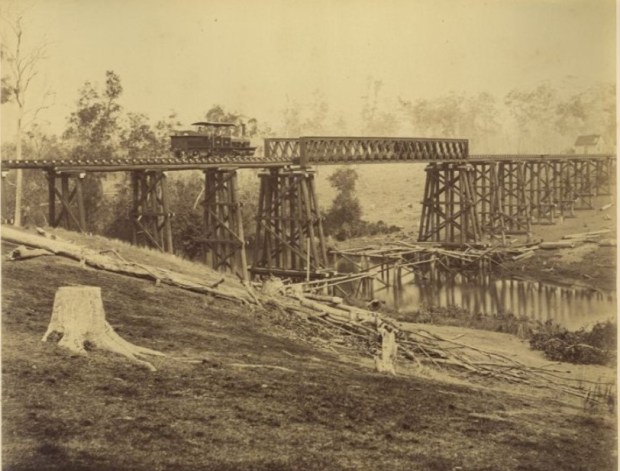

Scene from the Logan River at the time. (SLQ)

Mr Downman kept dairy cattle, and William found he had an aptitude for dairying. He remained on the Logan for years, where he demonstrated a talent for letter-writing for fun and profit that would serve him well in the future.

BACKACHE AND CONSTIPATION. Knapp’s Creek, via Beaudesert, Q., The Dr. McLaughlin Co. Dear Sir, — Just a few lines to let you know how I am getting on. I am pleased to state that there is a big improvement in the backache — it does not trouble me half as much as it did the last time I wrote, and I feel better in every way. I am very regular in my bowels, and I sleep like a top. I never remember being so regular in my bowels. I only hope that it will continue to keep getting better. I am yours very truly, WILLIAM H. CLEAVE. [iv]

By 1910, William and his miraculously regular bowels had relocated to Graham’s Creek in the Maryborough district. He set up his dairy farm and started his family. He also engaged in his other passions – letter writing, and being a thorn in the side of every bureaucracy he encountered.

“THAT OFFENSIVE LETTER. (To the Editor) Sir, – In your columns of the 17th inst, I see that the Antigua Shire Council had thought fit to call my letter to them most offensive, and it was consigned to the wastepaper basket. My letter has hit them in a very sore place, consequently it was called most offensive. I am sure that nine out of every ten ratepayers will agree with me when I state that the rates are altogether too high. Now, Mr Editor, I will try (writing from memory) to give you word for word that most offensive letter, and let you be the judge if the said letter was written in a most offensive tone or not. The letter:

“It seems to me that the Councilors are playing at the game of grab, for they are not satisfied with raising the valuations, but must raise the general rate as well, which is altogether beyond reason, considering the patched-up state of the roads. The Councilors ought to take a trip into some of the black soil country, when they would know how to make – or rather, would know what it costs to make – roads, yet the rates in the black soil country are not as high as here. Since I have been about this part, I have not seen a really good piece of the road in the district.” Thanking you, Mr Editor, in anticipation. I am, etc WILLIAM H. CLEAVE Graham’s Creek, January 27th, 1910.” [v]

Letter-writing for profit had supplemented his farm earnings on the Logan, so now William happily and publicly extolled the virtues of a brand of feed:

“Mr. William H. Cleave, of Graham’s Creek, writes us as follows, under date 28th May 1915. – Re Meggitt’s Linseed Meal, I give my cows a little more than you advertise as a sufficient feed, namely about 3 lbs (or a 7 lb. syrup tin full) for a feed, with a very liberal supply of Cornstalk Chaff viz, 2 kerosene tins at a feed, and I find that most of the cows that I am feeding (fresh cows) are giving just about double the quantity of milk that they were giving before I used the Linseed Meal. There is no doubt about it, it is good for Milk Cows, more especially fresh Cows.“[vi]

The Government put a stop to the good times in 1916 when it fixed the price of butter. William found himself unable to afford to feed Meggitt’s to his herd and fired off a letter to the Commissioner of Income Tax, which he also had published in the Courier under the by-no-means-inflammatory heading “HITTING THE FARMER.” Here is the final paragraph:

“Under the circumstances how is it possible for a dairyman to have any income when the Government come along and grind down the dairy industry, the only Industry where they fixed the prices below the market value? My wife and family have had to do without some of the common necessaries of life just through this upstart Government robbing myself and family of at least £8 to £10 per month. Butter at the present time is costing me about 2/6 per lb to produce, yet I have to sell it for 1/1 ½ per lb. If that is not robbery, I should like to know what is. Of course, might is right with the present Government.” [vii]

William, his farm, and his large family survived this setback – a fact which may have something to do with the resumption of his endorsement of Meggitt’s, who kept the ads running for a year.

In 1925, William applied to the Burrum Shire Council for the temporary closure of a road, and the Council agreed meekly, perhaps remembering the fallout after the 1910 letter in the waste-paper bin fiasco. [viii]

Two years later, his wife Jane took action against the Council for damages arising from her horse shying on the Kernovski bridge on Graham’s Creek Road and throwing her from her sulky. The bridge in question had a sizeable hole in it, which frightened the horse into a sudden stop. Otto Beikoff was contracted by the Burrum Shire Council to repair the structure, and he had put a large pile of stones near the bridge with a view to fixing the hole. Eventually. The Council decided to defend the action, and the judgment was reserved by the Magistrate after he heard all of the evidence. A good part of the evidence came from the plaintiff’s husband, one William Cleave. No doubt His Worship felt that discretion was the better part of valour.[ix]

In 1934, William’s eldest son John was united in holy matrimony with one Eva Jennett Murray. The Telegraph was pleased to note that the bride wore “a costume of crushed rose flat crepe and a fine straw hat to match. She carried a sheaf of blue delphiniums. On leaving for Southport, where the honeymoon is being spent, the bride added a mastic swagger coat to her costume.” (Mystified, I searched “mastic swagger coat,” and was hugely but pleasantly surprised when the Internet knew exactly what that was, and even supplied me with an image of same.) [x]

John was a hairdresser in Leichhardt Street, Spring Hill. He pled guilty to failing to keep his salon closed after the prescribed time of 5:30 pm, reasoning that busy city workers could not get to the hairdresser in time to comply with the regulations. He showed echoes of his father’s eloquence when he declared “There is no chance for people to get to a hairdresser,” which the Telegraph obligingly made their headline. [xi] No hairdresser could afford to turn away customers, he added. The Bench was unmoved. One quid, please. Plus costs.

Sadly, John passed away in 1938, just four years after he married Eve[xii]. John William was survived by both of his parents.

More than a decade later, William Cleave died at Maryborough, aged 86 years[xiii]. He was a well-known Maryborough identity and left behind a large and loving family when he passed away. Far from being crushed by the sorrow and misfortune in his early life, he seemed to use the experience as an impetus to build a farming business and create a devoted family. Any lingering anger he may have been dealing with from his childhood was quite sensibly directed at Shire Councils and Taxation officials.

[i] General Order No. 526 (Gazette 7 February 1872)

[ii] Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld.: 1866 – 1939), Saturday 2 March 1872, page 4

[iii] Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 – 1939), Saturday 2 September 1882, page 292

[iv] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Saturday 9 May 1903, page 9 (Advertisement)

[v] Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947), Saturday 29 January 1910, page 8

[vi] Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947), Tuesday 8 June 1915, page 5. Advertising

[vii] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Friday 11 February 1916, page 9

[viii] Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947), Friday 4 September 1925, page 2

[ix] Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947), Wednesday 10 August 1927, page 6

[x] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Friday 14 August 1896, page 4

[xi] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Wednesday 22 July 1936, page 6

[xii] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Wednesday 25 May 1938, page 16

[xiii] Maryborough Chronicle (Qld. : 1947 – 1954), Monday 29 August 1949, page 2