Dr. Frederick Cumming, M.D.

Ipswich

Dr. Frederick Cumming spent sixteen years in Queensland, living and working in Ipswich, Drayton, Brisbane and on the diggings near Gympie. Due to his somewhat combative nature, combined with a perhaps misguided desire to influence local politics, his time in the Colony was a turbulent one. In later years, he settled in New South Wales and enjoyed success, together with the respect of the public and his peers. But Queensland, the place after which he loyally named one of his sons (Victor Albert Queensland Cumming), did not respond well to his attentions.

Dr. Cumming arrived in Queensland in August 1854, as the Surgeon-Superintendent of the immigrant vessel, Monsoon. His wife and young family came with him, and he settled in Ipswich to practice medicine. There was at least one other doctor in town – Henry Challinor – and the two would irritate each other for years to come.

The Two Doctors

On October 27, 1854, Dr. Cumming won lavish praise from the Courier for his “strenuous and skillful efforts” [i] to revive two drowned children, and later that day attended on a young woman who had dropped dead. He arrived too late to do anything for her, and at a subsequent inquest Dr. Challinor gave evidence that he could not say what the cause of death had been[ii], because Dr. Cumming had not arrived until after the patient was already dead. A minor snipe, but it would be remembered.

On April 20, 1855, Mr. William Jubb, of Cunningham’s Gap, was driving a dray towards Ipswich, intending to go to Brisbane to seek treatment for his wife. Mrs. Jubb, who had been ill for quite some time, was resting in the dray. Nine miles outside Ipswich, one of the wheels of the dray struck against a tree, and it overturned, trapping Mrs. Jubb underneath. She was nearly dead when she was able to be freed from the vehicle. When Dr. Cumming arrived, she had passed away, and he waited in the rain with her husband until an inquest could be held. [iii]

The report in the Courier on Saturday 28 April 1855 sparked a spectacular war of letters and public advertisements between Doctors Cummings and Challinor. The report mentioned that Mr. Jubb’s brother had set out to Ipswich to get a doctor, “but nearly eight hours elapsed before a medical man arrived, when Dr. Cumming came up.”

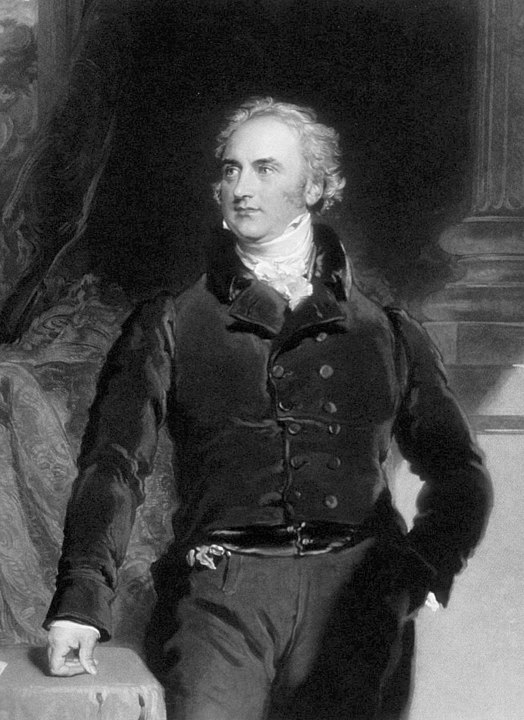

Henry Challinor in later years

Dr. Cumming detected “a tone of complaint” [iv] in the report and wrote to the Courier to explain the delay in a medical man attending Mrs. Jubb. He helpfully recalled the depositions of the inquest, showing that he had been out with a patient at the first time Mr. Jubb’s brother called, and Dr. Challinor had asked to take the call. Dr. Challinor initially agreed to go but thought better of it because of the rain and the state of the roads. He (Dr. Cumming) was then located, and agreed to go to the scene, but found that Mrs. Jubb had passed away.

“I sincerely sympathise with Mr Jubb in his loss, and can duly estimate the effects of the weather, having myself been exposed to it, and the risks of the road, during the night of the sad accident.” Dr. Frederick Cumming.

Just how ‘called-out’ Dr. Henry Challinor felt as he perused the Saturday papers over his breakfast would be borne out in the following edition of the Courier. Dr. Challinor wrote that he had indeed changed his mind about travelling in the rain to tend a woman who had, he said, already died. He didn’t mind Dr. Cumming exonerating himself for the perceived slight of tardiness, but,

”When he travels out of his way to inform them of what occurred before he was called upon to attend, a suspicion immediately arises that his object was not so much to justify himself as to criminate another.” Dr. Henry Challinor.

In other words, keep my name out of your mouth. Dr. Challinor went on to set out his history of providing medical care in the town of Ipswich, and darkly hinted that people in glass houses should not throw stones.

A week later, Dr. Cumming put his reply in an advertisement addressed to the Editor[v]. The space restrictions applying to the Letters to the Editor column would not hold him for this one. He addressed nine numbered paragraphs in self-defence (although when published, number six was missing). He taunted Challinor in verse, alluded to several Dickens characters, and then added:

“Physician, heal thyself, throw not insinuations at my glasshouse, thine may be smashed by hard facts. There is a fish which when pursued or alarmed emits a filthy inky fluid to discolour the water, so as to prevent its being seen, and to favour its escape.”

Naturally, that wasn’t going to stand. Dr. Challinor responded the following week, also in the classifieds.[vi] He brought up the case of a child with a broken thigh, who was not attended to by Dr. Cumming until the following morning. He mentioned a woman named Linsdsay, who had refused to do “Mrs. Cumming’s heaving washing” by way of payment for his treatment of her son’s bowels. Scandalous stuff.

“Having recovered from the wonderment occasioned at the thought of Dr. Cumming’s amazingly rich stores of Select Poetry, as manifested by the choice couplet he quoted, I carefully examined the contents of his rejoinder, (which neither in its spirit or style reflects much honour upon the medical profession).”

Dr. Cumming’s response was a nearly 1200-word letter[vii] in which he made extensive use of italics, and included use of the terms, “Sly, impertinent, whining hypocritical outcry, old woman’s twaddle, disgraceful, absurd, and ungentlemanly.” On the subject of the heaving washing story, he became incandescent, and invoked the names of Lord Palmerston and Sir Astley Cooper as referees.

Dr. Challinor decided not to reply, at least in public. That was probably for the best. Stethoscopes at dawn was not the best advertisement for Ipswich’s medical community. Afterwards, the two men met several times in a professional capacity, and one can only imagine the degree of frostiness between the two men.

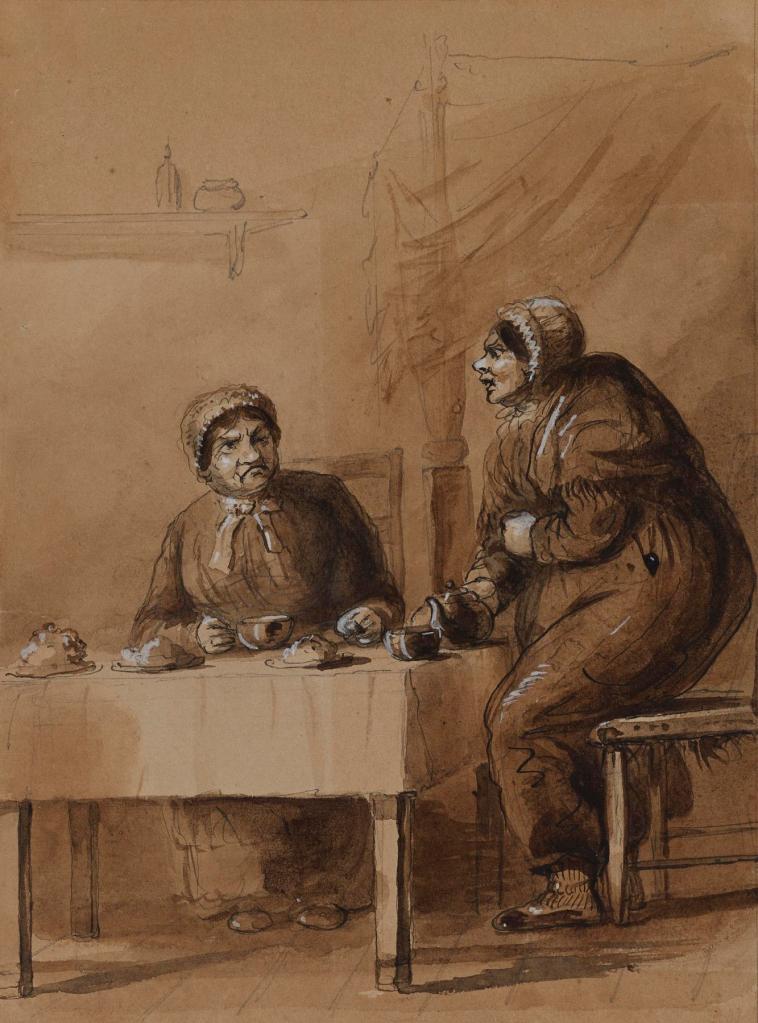

“Have you heard? Those doctors are at it again!” (Group of men, Ipswich, 1859.)

A Meeting Extraordinary

In April 1856, a meeting of residents was called to discuss the setting-up of an Ipswich Hospital. The gentlemen who spoke included various local worthies – Mr. Walter Gray, Colonel Gray, Arthur Macalister, Mr. Faircloth and Dr. Cummings.

It was argued, quite reasonably, that transporting the sick and injured of the district to Brisbane was dangerous to patients, and that a subscription service should be set up to assist the labouring classes. So far, so good.

From the Courier’s published account of the meeting, Mr. Walter Gray seemed to have turned up just to interrupt and torment Dr. Cumming. (I suspect that the good doctor may have possessed a somewhat haughty manner, which led the more raucous inhabitants of Ipswich to use his public appearances to taunt him.)

“Dr. CUMMING addressed the chairman and estimated, that before the motion should be put, he was desirous of offering a few observations to the meeting-and began by alluding to the shortness of the notice, when Mr. Walter Gray burst forth with “No, no, no—haw, haw, haw! You’ve got as much notice as I had, and I’m sure I’m of as much importance as you; I’m of more importance than you, haw, haw—you’re a fool, a fool, hi, haw, haw.” [viii]

When Cumming protested to the chair, the chairman (Colonel Gray) refused to do anything about it. The interruptions went on, climaxing with the following:

“Mr. Gray rose up, and with rolling eyes, and inflated visage, commenced roaring at Dr. Cumming, and bullying with violent gesticulations; and when the Doctor requested him to desist, as he did not come to the meeting to argue with the chairman, he roared out “Argue with you-I’ll argue with you anywhere. Come outside (threateningly) and I’ll argue with you;”-and so saying, he rushed out of the room, and the meeting broke up amid the merriment of the persons assembled.”

Dr. Cumming did not trouble himself further with arguments in the Hospital Committee. It was likely to be a bear-garden, as the Courier had observed. Soon, Dr. Cumming would remove to the loftier environs of the Darling Downs.

The Hospital Committee, no, sorry – an actual bear garden. (Cruikshank.)

The Challinor/Cumming Correspondence, 1855:

SIR-From the tone of complaint in your article under this title contained in your last number, and the circumstance of my name being mentioned as the medical man who proceeded to the scene of the accident, I feel bound to say that no unnecessary delay took place in my attendance. I was from home, visiting a patient when it was first desired, but when informed of the accident, about ten o’clock, I proceeded with as little delay as possible, and arrived at the place, which is about ten miles from Ipswich at about one o’clock A.M., the darkness of the night, and bad state of the roads impeding our progress. I cannot give an extract from the deposition, on the Magisterial inquiry, as the papers have been forwarded to Sydney; but I may say that the deposition of Constable Laidler explains the chief cause of delay. He deposed to the effect “That when Mr. Jubb’s brother arrived in Ipswich, about half past six o’clock P.M., he and the constable were proceeding to the residence of Dr. Cumming, when they were informed that he was out, visiting a patient; that they then went to Mr. Challinor, who agreed to go with them, and went out to the neighbourhood of the burial ground for his horse, and returned with it, but after some conversation, finally declared that the night was such and the roads so bad, that, in justice to himself and his friends he could not consent to go till the morning; that they went to Dr. Cumming, who immediately on procuring a horse set out with himself (Laidler,) for the place, where they arrived as he supposed between one and two o’clock on the 21st.

I sincerely sympathise with Mr Jubb in his loss, and can duly estimate the effects of the weather, having myself been exposed to it, and the risks of the road, during the night of the sad accident. I am, Sir, Your very obedient servant, FREDERICK CUMMING, M.D., Surgeon. Ipswich, 1st May, 1855.

Sirs,-In reply to a letter contained in your columns of the 12th inst., signed “Frederick Cumming, M.D., Surgeon,” I beg to state that it is quite true “that when Mr. Jubb’s brother called upon me I agreed to go with him,” it is also quite true “that I went to the neighbourhood of the burial ground for my horse and returned with it,” and further it is quite true “that after some conversation I finally declared that the night was such and the roads so bad, that in justice to myself and my friends I could not consent to go till the morning.” But then this is not the whole truth. There is an omission, an important omission, an omission which given a different colouring to the whole affair – namely the principal reason I assigned for not going – the only reason indeed which made the other reasons reasonable -I mean the circumstance of Mrs. Jubb being dead before the messenger was dispatched for medical aid -whether this omission is owing to a failing in Dr. Cumming’s memory or inadvertence in constable Laidler when giving his evidence, I cannot under-take to say, having neither heard nor read “the depositions,” but this I do know, that every individual who is more desirous to state a thing as it really is, than as he would like it to appear, will be very solicitous to declare the whole truth, as well as the truth and making but the truth. Doubtless it was very fit and proper that Dr. Cumming should reply to any published remarks of yours which he considered affected him injuriously, and if he had contented himself with saying “that he was not informed of the accident, till about ten o’clock, when he proceeded with as little delay as possible, and arrived at the place, which is about ten miles from Ipswich at about one o’clock, A.M., the darkness of the night, and bad state of the roads impeding his progress,” the public would certainly have exonerated him from all blame in the matter. But when he travels out of his way to inform them of what occurred before he was called upon to attend, a suspicion immediately arises that his object was not so much to justify himself as to criminate another. However, under the very deep distress of mind and almost insupportable confusion occasioned by his very disinterested and highly judicious, severe, yet well merited castigation of my want of humanity, it affords me some little consolation, it is some trifling mitigation of my well-nigh overwhelming sorrow and remorse, to think that my conduct on that occasion did not altogether unhumanise me in the opinion of either constable Laidier or Mr. Jubb for both have placed themselves under my professional care since the occurrence of that fatal event. A residence of more than six years amongst them has afforded the inhabitants of these districts abundant opportunity of judging whether I am the timorous and unfeeling practitioner Dr. Cumming would represent me to be, and it is my happiness also to add that of late years, (with very few exceptions) I have no cause to complain of their want of a due appreciation of my assiduous attention to my professional duties. Be this as it may, I have on several occasions of emergency travelled all night in the bush, and have done so since the death of Mrs. Jubb, and “can duly estimate the effects of the weather, having myself been exposed to it and the risks of the road,” for it was a very inclement “night.” But then, in each of those cases, I went to see a patient – not a corpse.

But to return to my refusal in question. What is Mr. Jubb’s view of it as he expressed it to me himself on Saturday last (many hours before the arrival of the Courier in this town)? “that he could not blame me, for now that his feeling allowed him to reason dispassionately, he saw I was right.” Could a sensible man come to any other conclusion? Surely it is enough that a medical man adventures his life and limbs when he has a prospect of benefitting the living; without being called upon to risk either for the sake of the dead who are utterly beyond the reach of the ” Healing Art.” At any rate, I think that a due consideration for “myself and friends,” and some anticipated calls, which induced me on that occasion to decline going on a perfectly useless and to some extent hazardous journey, was quite compatible with very “sincere sympathy for Mr. Jubb in his loss.”

In conclusion, I would recommend to the worthy Doctor’s attention the somewhat ancient perhaps, but nevertheless prudent maxim, “that persons who live in glass houses should not throw stones.” A little reflection, if his memory is not very bad, will point out to him the personal application. I am, Sir, Yours, Sinc., HENRY CHALLINOR .M.B.C.S. Eng., L.A.A. Lon, doc.

[Mr. Challinor has an undoubted right to be heard in his own defence, and might think him-self injured if we curtailed his communication, but he makes a most unmerciful demand on our space.-ED. M. B.C.]

” My Aunty Kate came down the gate, And sorely scolded me.”-Old Song.

SIR, In your last number, Mr. Challinor tries to wriggle out of his little difficulty by accusing me of travelling out of my way to attack him, &c., and seems sadly afraid that his glasshouse maybe smashed in the skirmish. Would you allow me to inform him

1st. That I did not write to criminate him, but to defend myself.

2nd. Constable Laidler did not and could not state that Mrs. Jubb was dead before the messenger was sent to Ipswich. The messenger (Mr. Jubb) was sent in post haste to bring a medical man as soon as possible, as Mrs. Jubb was lying insensible and might be dead before one could arrive -at the place-whatever he said to Mr. Challinor – he certainly urged my instant departure on these grounds. It is the whole truth that makes the galled jade wince, if I had suppressed the truth as to his refusal to go to the injured woman he would not have complained of the omission, the important omission.

3rd. I am sorry to pluck out any of the feathers in which Mr. Challinor bedecks himself before your readers, but I may also inform him that Constable Laidler appointed to meet me at my house on the morrow after the inquest, but did not come, I fear from an impression erroneously received from words of mine that I did not care to advise him, and, as to Mr. Jubb he has since told me that he was sorry he did not know my address on the night when he was assisted by a friend to Mr. Challinor’s house, and proposed putting himself under my care, which I declined.

4th. I did not represent Mr. Challinor to be timorous or unfeeling, he seems to think the facts do so represent him.

5th. My mention of the weather, my being out all night, &c, were to meet the supposed complaint in the notice of accident in the Courier and had no reference to Mr. Challinor.

6th. Mr. Challinor was not told and could not know that Mrs. Jubb was a corpse when his assistance was asked for her. He at first consented to go-was it to visit a person known by him to be a corpse.

(There was no 7th in the letter as published)

8th. He says Mr. Jubb has become so sensible that he does not blame Mr. Challinor now, consequently we are to infer that he did blame him at the time of the accident. Mr. Jubb informed me that Mr. Challinor was the person he pointed at in his advertised letter on the subject as the one exception to the general sympathy shown to him on the occasion. It was because some might suppose that it pointed at me that I did express my sympathy in my published letter.

9th. I wrote to you, Sir, in order to obviate from myself a supposed injurious tendency of your notice of the accident, and incidentally but necessarily related a fact deposed to at the inquest. Now, Mr. Challinor, because that fact bears against him, writes a long scolding letter against me, and tries to have his revenge by throwing out an insinuation. He may be a fair correspondent in one sense, but insinuations won’t do; let him speak out like a man; my memory is not good enough to recall on reflection anything to which his insinuation can refer. I may retort to your fair or unfair correspondent, Physician heal thyself, throw not insinuations at my glasshouse, thine may be smashed by hard facts. There is a fish which when pursued or alarmed emits a filthy inky fluid to discolour the water, so as to prevent its being seen, and to favour its escape. I recommend the personal application to Sairey Gamp, Mrs. Harris, Henry Challinor, or “to whom it may concern,” and if their memories are bad, advise them assiduously to study the Moreton Bay Courier, of date May 19th, page 2nd, column 5th. I am, Sir, Your obedient servant, FREDERICK CUMMING, M.D. Brisbane, May 22.

Sir-Having recovered from the wonderment occasioned at the thought of Dr. Cumming’s amazingly rich stores of Select Poetry, as manifested by the choice couplet he quoted, I carefully examined the contents of his rejoinder, (which neither in its spirit or style reflects much honour upon the medical profession) and as I did not find in it the slightest ground to justify him in introducing my name to the public in the manner he did, I still hold him guilty of a disreputable attempt to injure me in their good opinion; for if it were necessary for him to confirm his own statement of facts reflecting upon himself by a reference to the depositions, he could easily have culled out whatever bore upon that point, and left it to some other disinterested friend of humanity to shew up the delinquent by publishing what referred to myself.

Post haste is a very vague term to describe the period that elapsed between the overturning of the dray and the dispatch of the messenger, and the extent of his knowledge of the injury inflicted upon Mrs. Jubb, and by no means excludes the idea that he might have said in the hearing of constable Laidler, what he said to me in the presence and hearing of the Chief Constable, “that he was sure she was dead.” From his subsequent conflicting statements, I think it is more than probable that his previous want of success induced him to make a more favourable representation to Dr. Cumming, than in the first instance he did to me, but I do not see how that circumstance qualifies Dr. Cumming to make such an unqualified assertion as to the nature of the messenger’s communications to myself, which fortunately can be confirmed by an independent witness. But his whole epistle shows that his inductions are as illogical as his conduct is ungentlemanly.

I have no objection whatever to visit a corpse when it suits my purpose, and had the night been favourable would gladly have gone to examine Mrs. Jubb’s remains, knowing that, Mr. Jubb would have handsomely remunerated me for the service, and that by waiting till morning I could only claim a solitary guinea for a compulsory ride of nine miles, and attendance at a magisterial enquiry; but a little reflection while procuring mv horse, convinced me that in more senses than one I might be “penny wise and pound foolish” in yielding to the pleasure of that pecuniary motive, and therefore on my return declined going. I never for a moment doubted that Mr. Jubb alluded to this circumstance in his advertisement, but as my name was not specially mentioned, I did not feel that I was specially called upon to reply to it. I may observe in passing, that though Mr. Jubb said nothing which could in any way detract from Dr. Cumming, yet their versions concerning his consulting Dr. Cumming do not at all agree, and as I came honestly and honourably by my feathers, I may still wear thein without shame or fear.

I will now endeavour to “speak out like a man,” by refreshing the Doctor’s memory with the following facts-(I take them to be hard facts) -Late one night, several months ago, he was requested to go 40 or 50 miles into the bush to visit a boy who had broken his thigh, but he did not set out till early the following morning. Now, I do not blame Dr. Cumming for not going that night –I do not say he ought to have gone -perhaps he was not desired to do so-or he might have had no guide – or his horse might have been lame (I believe it was); – but then, according to his own statement, if he could only have got him 14 miles on the road, he could have procured a fresh one-probably a guide if requisite.-True, by starting at that time of night, he might have lost his way and got bushed-or his horse might have knocked up before he arrived there. But what of all that, or much more? Thoughts of a bereaved widow-or a parcel of helpless orphans or of a broken leg-or a fractured collar bone-or a phthisical cough-or a wasting sickness-or incurable pains-are not -supposed to form any part of the reflections of a model “M.D Surgeon.” But we fancy him exclaiming, with all the fervour of poor ” Nolan”,- “There is the patient -and such and such his claims upon my professional skill-to the rear ‘personal considerations’-advance ‘sympathy’ ‘post haste’ to the relief of the sufferer’ – and behold him galloping rapidly away to the scene of duty.

Again, a person of the name of “Lindsay,” a few months since, wished me to visit her child, which Dr. Cumming had refused to attend. This is her account of the matter. While on board the Monsoon, the child had a severe affection of the bowels, from which it recovered under Dr. Cumming’s treatment. On its being taken very ill in this town, she again had recourse to him, with the hope that his treatment of it on shore would prove equally successful-but he persisted in his refusal to go, because she had been equally persistent in refusing “to do Mrs. Cumming’s heavy washings.” This (if correct) is certainly only a quid pro quo argument in everyday use; and it is quite unnecessary for me even incidentally to discuss its merits or demerits in the present instance. I only introduce it as on additional illustration that personal and family considerations do occasionally enter into the Doctor’s calculations before decides whether he will or will not attend to an urgent professional call.

The persons referred to in italics (my acquaintance with whom is much more recent and imperfect than Dr. Cumming’s) can act as they think proper. For myself, I shall deem it worse than useless to waste either ink or paper upon his future communication, unless written in a manner more becoming the profession of which his former effusions prove him to be so little worthy. I am, yours, &c., HENRY CHALLINOR, Ipswich, May 31,1855. M.R.C SC. Eng, &c.

“My Auntie Kate came doon the gate, and sorely scolded me.”

SIR, – My opponent of the couplet, who professes to be a determined stickler for the whole truth, raises all this whining hypocritical outcry about my making an attack upon him with a view to injure him in the opinion of the public, and says it is ungentlemanly to state the truth when it reflects upon him, and brings his name into disrepute. Such truths should be called out. He is a Daniel come to judgement on that point certainly.

But the said attempt consists in a statement of the whole truth as to the manner in which eight hours had passed from the time at which a passenger arrived in Ipswich in search of medical assistance, to that at which the assistance as represented by myself did arrive at the requisite point in the bush, three or four of those hours having been wasted in an attempt to procure Mr. Challinor’s attendance. Again, Sir, notice the respect of Mr. Challinor for the whole truth. He says he was perfectly convinced from the first that Mr. Jubb’s complaint or denunciation of the one exception to the universal sympathy shown to him on the occasion of the accident referred to himself – yet he did not feel called upon to reply to it, as he was not specifically named. That is to say, that he would by sneaking in a corner, by concealing the truth, allow the denunciation to fall on the shoulders of some other person, mine, for instance, as I was specially mentioned in the Courier’s notice of the accident. The compliment was meant for him, let him wear it. The delay complained of by Mr. Jubb was his delay, let him answer for it. The person of the name of “Lindsay” and her child WHICH? – were patients of mine, when I had no alternative, I have handed them over to Mr. Challinor, let him also keep them. By the way, Sir, and talking of bereaved widows, some very sly or impertinent persons have given their opinion that one of the reflections which caused my opponent to decline to comfort the bereaved husband at the nine-mile waterholes was an excusable preference for comforting a bereaved widow.

Now for the squeak or attempt to speak out – if correct – aye, mark his words, – and write them in a book, if correct. They are not hard facts, even if correct. They are not facts at all in relation to Jubb’s case.

Squeak the first – Late one night, some months ago, I was requested to go on the following morning 50 or 60 miles into the bush to see a boy who was supposed to have broken his thigh. I went accordingly in the morning without a guide, found that there was a fracture, set the bone, applied the apparatus and returned home. The boy had a good recovery. There was neither refusal nor delay. The whole of Mr. Challinor’s paragraph on that case is mere old woman’s twaddle.

Squeak second – The person of the name “Lindsay,” her husband, and also the child, which were all dangerously ill, on board of the Monsoon, but recovered. The child, which was a robust boy when I saw him last. The person of the name of “Lindsay” urged me to visit the child, but that does not constitute an urgent case; for between her first and second calls there elapsed about twenty-four hours. I never assigned as a reason for my refusal anything connect with washing – either light or heavy, – I at first truly assigned indisposition, and on both occasions, I advised her to call in Mr. Challinor, or either of the two other medical men who were in Ipswich at that time. There was plenty of assistance at her service. When she came to reside in Ipswich, Mrs. Lindsay called at my house and asked to be employed in washing, &c., she received all she asked for her service, and much more, professed to be satisfied and thankful, and was exuberant in her declarations that I had saved her life – that she would never have seen Australia but for my persistence and care of her, and would do anything in the world for myself and family. When the person of the name of “Lindsay” is capable of telling her chum of the name of “Challinor,” such a heavy washing story as that contained in his letter – which, if spoken by her, is equally disgraceful to her whether true or false, your readers will be aware of my reasons for objecting to her being employed in my house, even under the urgent case of a want of servants at the time, and will not be surprised that I should decline to be installed as a family doctor to her establishment where she could plead that there was no other to be had. I sent her to the congenial person of the name of “Challinor,” who, I hope, will wear her as a bright feather in his cap, or bonnet.

That story, even if correct, as my opponent properly adds, which it is not, however, has no relation to or similarity to Jubb’s case; it is only a disreputable attempt to throw soap suds in the eye of the public. In the person of the name of “Lindsay,” the person named “Challinor” has acquired a chum worth Sairey Gamp – Betsy Prig – and Mrs. Harris, all put together. My present style certainly reflects no credit on the profession in the person of the name of “Challinor” – it is contemptuous – and such is likely to be my style to that “person,” except when thrown by chance into such contact professionally as the public necessity and safety may dictate.

I am afraid of killing my opponent outright, and so becoming guilty of Aunt-icide or at least of throwing my relative into hopeless wonderment, but he will have it so – and I must therefore beg him not to be alarmed as to the style and spirit of my effusions, as I can shew him a letter from a better judge than he is – to wit, a person named “Lord Palmerston,” who gives his opinion that some of them are very excellent, – and further, as to my worthiness of my profession, another letter from its brightest ornament – a person named “Sir Astley Cooper” – which he concludes with the following words: – “I am delighted to thus commence a correspondence with you.”

I rather imagine that my present correspondent will be as much delighted when I leave off this, as Sir Astley was to begin that correspondence. And indeed, he shows some signs of common sense when he says he won’t write any more letters in answer to mine. When he has descended to the child which and the washing tub, surely absurdity and twaddle can go no further. So, I shall conclude with but one parting couplet, a little altered from the original – “Fare the well, and if for ever, Still, my Aunty, fare the well.” I am, Sir, Your very obedt. servant, FREDERICK CUMMING, M.D. and Surgeon, Ipswich, June 12th 1855.

Part 2 – Toowoomba and Politics

[i] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 4 November 1854, page 2

[ii] The patient, “a young woman, who was somewhat full in figure, had been in the habit of tight lacing.” This was given as a contributing factor in her death. She was not publicly named, poor thing.

[iii] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 28 April 1855, page 2

[iv] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 12 May 1855, page 2

[v] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 26 May 1855, page 2

[vi] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 9 June 1855, page 3

[vii] Advertising – The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861)Saturday 16 June 1855 – Page 3

[viii]Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 26 April 1856, page 2.