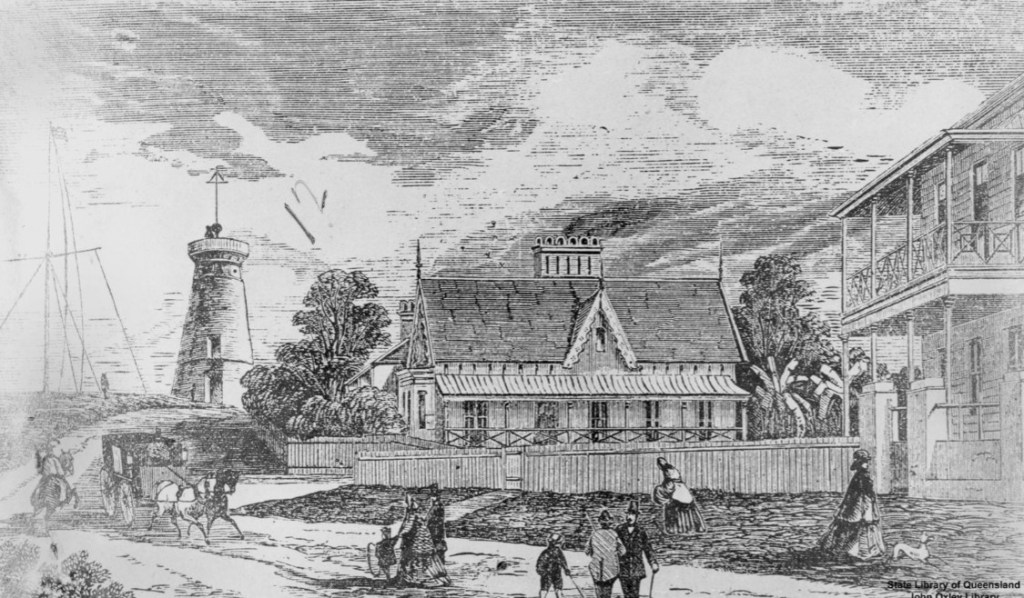

Dr. Frederick Cumming in the 1860s.

Henceforth, apart from one (disastrous, of course) toe-dip in the politics of West Moreton in 1867, Dr. Cumming would be known for his medical practice. There would be controversy, financial problems and some rather questionable verse. His experience of Brisbane in the 1860s would culminate in his return to England.

A few months after the Ipswich election debacle, Frederick Cumming Jr., who had survived an encounter with a snake a couple of years earlier, gave his father another scare. Frederick and his gloriously named friend Grosvenor Francis went out bird shooting in the bush near Bowen Bridge. Young Grosvenor shot at a bird erupting from some bushes, forgetting that behind them young Frederick was waiting to take a shot. Frederick was hit in the thigh and badly wounded. Luckily, some passers-by were able to get him to his father’s house, where Dr. Bell (another medico involved in political life) was called in to treat him. It was considered too dangerous to remove some of the shot, which was close to the bone. The boy mercifully recovered. [i]

The Beebee Case

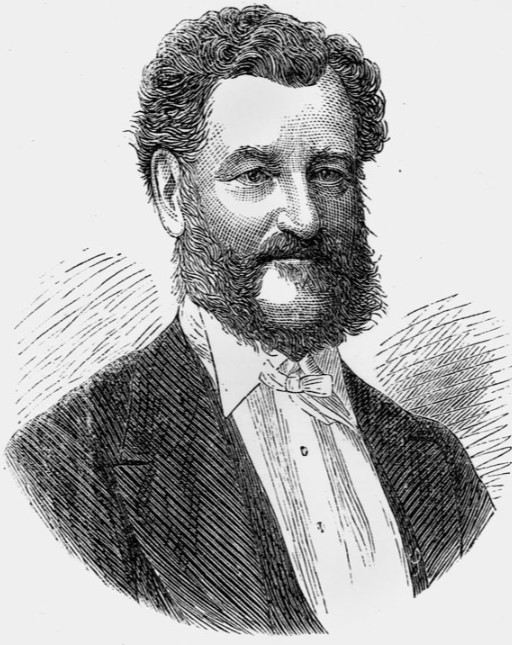

In February 1862, Dr. Cumming was called upon to go to Durundur Station to treat a woman named Beebee, who had allegedly been badly beaten by her husband. Durundur was 50 miles north of Fortitude Valley, and of the 22 gazetted medical practitioners for the colony of Queensland, there were none closer to the station, apparently.

Frederick Cumming set out by horse and cart on Sunday, when he heard of the assault, which had occurred on the Saturday night. When he arrived a day later, the woman had died.

Durundur Homestead (sketch by Charles Archer)

Saturday was drinking day on Durundur, and station worker Henry Beebee took part in the merriment. That afternoon, neighbours heard Beebee and his wife arguing in their hut, which was unusual for the otherwise quiet and happy couple. After hearing the argument, a neighbour named McReynolds went to the Beebee hut, and found Mrs. Beebee lying unconscious, face-down on the floor. McReynolds and his wife helped the woman to sit up, and gave her some first aid, which revived Mrs. Beebee enough to remark that her neck was broken and that she would never recover. She lingered for more than a day, finally dying early on Monday morning. [ii]

Dr. Cumming arrived on Monday evening and conducted an examination of Mrs. Beebee’s body on Wednesday afternoon. The reason for the delay was a technical and legal one – he was called to examine a patient, not to conduct a post-mortem. A Magistrate had to order an examination, and it turned out that Magistrates were as thin on the ground as doctors. When one was eventually located, and the direction to examine was given, it was Wednesday afternoon. [iii]

February is the hottest month in Queensland, and Mrs. Beebee’s body was not in good condition after three days. When the examination (external) was conducted, Dr. Cumming could not find evidence of any injuries serious enough to cause her death. He was not requested to perform a post-mortem. This became a serious issue in the press and at subsequent court hearings.

By following the letter of the law, Dr. Cumming opened himself up to a great deal of criticism. However, had he performed an unauthorised examination or post-mortem, the evidence would not have been admissible.

At the committal hearing Arthur Macalister appeared for Henry Beebee, instructed by the Durundur Station Superintendent. Macalister must have thanked his lucky stars that his old Ipswich electoral opponent, Frederick Cumming, had followed the letter of the law at Durundur. He was able to argue in all sincerity, that as Dr. Cumming had found no marks of violence on Mrs. Beebee, there was no evidence of an assault by her husband, beyond what had been told by the dying woman to her friend. No dice, though. The matter was serious enough to commit Beebee for trial. [iv]

When the matter came to trial at the Supreme Court in Ipswich in May 1862, the Attorney-General, Ratcliffe Pring, prosecuted. He did not thank his lucky stars for Dr. Cumming. In fact, he complained that Cumming’s behaviour was “disgraceful,” and that it prevented him from putting the case to the jury as it should have been. The jury was unable to agree on a murder verdict, and the matter was remanded to be re-tried. At that trial, the prosecution decided to proceed on a reduced charge – that of manslaughter. The jury acquitted Henry Beebee of all charges. [v]

A scandal arose at the close of the Beebee case, but for once it was nothing to do with Frederick Cumming. A letter to the editor of the Courier under the hand of “Justitia,” pointed out the impropriety of Arthur Macalister appearing as a defence barrister for a person accused of a capital crime. “Justitia” noted that Arthur Macalister had accepted a fee and brief to represent Beebee at the committal hearing. He was, after all, “a member of the Executive Council defending a man on whose life or death he might subsequently be called on to decide at the council table of the Governor.” It appeared that Mr. Macalister had simply forgotten the bit about declaring the earnings and appearing in a private capacity. [vi]

Soon, the better-known legal and political figures of Ipswich and Brisbane entered a brief, but intense, skirmish in the letters pages.[vii]

A correspondent calling himself or herself “Chubb’s Patent” raised an allegation that Charles F. Chubb, a future judge, had written the “Justitia” letter to denounce Arthur Macalister. Chubb protested manfully. So manfully that the Queensland Guardian was forced to deny that Macalister was writing letters under the “Chubb’s Patent” pseudonym. [viii]

In the Courier, “Veritas” hinted that Ipswich legal men George Thorn and Hugh Stowell having been somehow involved in the “Chubb’s Patent” letter, or at the least, altering the name of the barrister on the Beebee brief. Denials burst forth.[ix]

The North Australian rose to defend Mr Macalister against charges of impropriety – he had accepted Beebee’s brief, they said, before he accepted his Ministerial post. This was something that might have been said at the outset. [x] (Once the committal hearing had finished, Mr. Jones represented Beebee as counsel.)

Doctoring On

Frederick Cumming had kept out of the Macalister scandal and spent the rest of 1862 taking part in medical work and civil affairs without incident.

1863 saw Dr. Cumming miss out on the House-Surgeon job at Brisbane Hospital, [xi] following the death of Dr. Barton. He was appointed to the Government Medical Board in October, as was his old nemesis, Dr. Henry Challinor.[xii] They must have been delighted to see each other at the meetings.

The following year, Frederick Cumming missed out on the House Surgeon position at Brisbane Hospital. Perhaps his disputatious reputation preceded him. Happily, the doctor was able to enjoy the Caledonian Society meetings and functions without incurring anyone’s wrath. [xiii]

Dr Cumming relocated to Wickham Terrace, starting a grand tradition of Brisbane doctors and specialists occupying chambers on the narrow, winding street at the top of Spring Hill. From this lofty position, he offered vaccinations every Monday and Thursday. He would be a prominent vaccinator for the rest of his life. [xiv]

In June 1866, everything started to crumble. The property at Wickham Terrace, along with other nearby lots, was advertised for sale, and his wife Agnes gave birth to a stillborn daughter on June 4. [xv] A month later, Agnes passed away at the age of 43. [xvi]

In his grief, he had trouble paying his bills, and a tuition debt led to the threat of a bailiff sale of his furniture and horses in December. [xvii] The sale was averted, but by then, his creditors were taking him to the petty debts court and court of requests on an almost monthly basis. [xviii]

At this unhappy juncture, politics called again, and he went through the embarrassment of being overlooked for East Moreton in July 1867. [xix] He took it quietly, and the letters pages of the local papers were left unmolested.

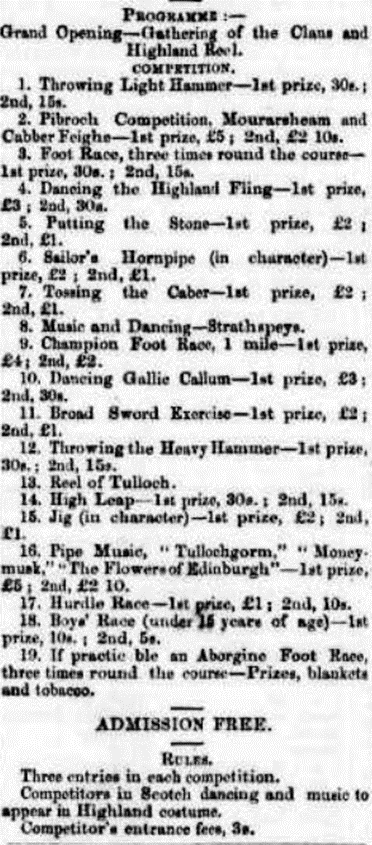

January 1868 saw the Doctor, in his capacity as a committee member of the Caledonian Society, making enthusiastic plans for the impending visit of the Duke of Edinburgh. [xx] They planned to amuse His Royal Highness thus:

The proposed Royal Reception by the Caledonian Society. I do hope that no indigenous person obliged the organisers by participating in Item 19.

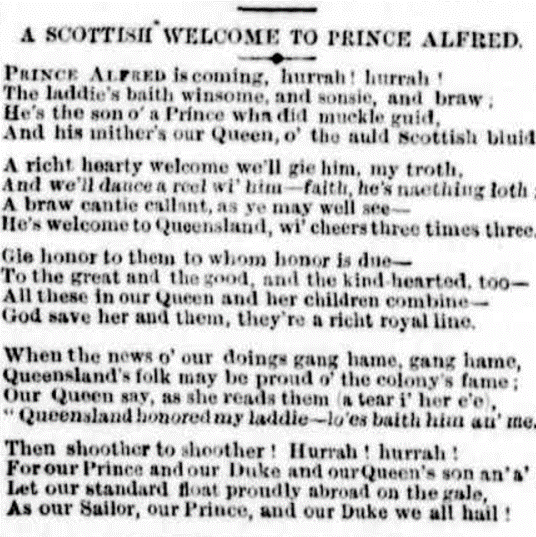

On Saturday 01 February 1868, he addressed the editor of the Courier for what would turn out to be the last time, agitating gently against the use of the “large room” of the Town Hall as the venue for a welcoming ball. He even wrote a poem.

“Meantime, as when our feelings are up, we sometimes like to give expression to them in song, I have strung together some verses which we may croon over till we get something better. Try “Prince Alfred’s Welcome” now, and alter it to the time present when he comes, and excuse yours truly, FREDERICK CUMMING.”[xxi]

No, I wasn’t going to type that lot out for clarity.

A wag called “Parcelus Jr.,” wrote to the editor, suggesting that Dr. Cumming’s poetry could be used to cure meat, thus saving men of science and industry a lot of trouble and expense. [xxii]

In April, his property at Lot 13, Wickham Terrace was put up for auction “at the risk of Frederick Cumming.” It was described as six-room brick and stone house surrounded by 5-foot verandahs and a balcony at the front.”[xxiii]

By this time, Dr. Cumming was no longer in residence. He had set up a practice at Nashville, near Gympie.

DR. CUMMING, LICENTIATE of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, 1827. M.D. of the University of Edinburgh, 1832. Member of the Medical Board of Queensland, has commenced the practice of the Medical Profession in all its branches at Nashville. RESIDENCE on the Ridge, near the entrance to the One-Mile Creek Township. [xxiv]

“In default of making our laws (he) is endeavouring to mend our bodies,” noted the Courier’s correspondent on the Jimna diggings. [xxv] Dr. Cumming remained there for at least the rest of 1868.

He had gone from being a Government Medical Officer who practiced at Wickham Terrace to pulling teeth in the camps at the diggings. Queensland had reduced him to this.

Dr. Cumming returned to England at the end of the 1860s, residing in Hastings until news from North Queensland brought him back to the Colonies. His second son, Walter, had died after falling from a horse in Cooktown on 2 November 1875.

The inquest into the death of Walter Scott Cumming, a clerk who had been residing in Cooktown, revealed that Walter Cumming had been “insensible” for a short while after the fall from the horse, but regained his senses and walked home with his companions. When he arrived at his Inn, he had a cup of tea and refused a doctor, saying “I don’t think there’s much wrong with me.” He did, however, ask if his brother could be located at the miner’s camp.

Walter Cumming’s condition became worse as the night wore on, and his brother Frederick was located at the digger’s camp behind the local hospital. A friend urged him to come quickly to Walter or he may be too late. Frederick found his brother in a “dying state,” and called for a doctor, who arrived in time to declare life extinct. Walter had been in Cooktown about 5 weeks. [xxvi]

Life in New South Wales

The following year, Dr. Frederick Cumming moved to Grenfell, New South Wales. His fortunes changed considerably in the sister colony. Within a year, he was the Medical Officer to the Grenfell Hospital. [xxvii] In 1877, he was a Government Medical Officer and official vaccinator. He kept the petty debts court busy, but it was in pursuit of unpaid bills, rather than defending debts.

Cumming became a member of the Ryde Druids[xxviii] and moved to Woollahra, where he became an office-bearer of the Woollahra Literary Institute. He recited poems to St. Ann’s Literary Institute. [xxix] People liked them. He had no need to write scalding letters to any editors.

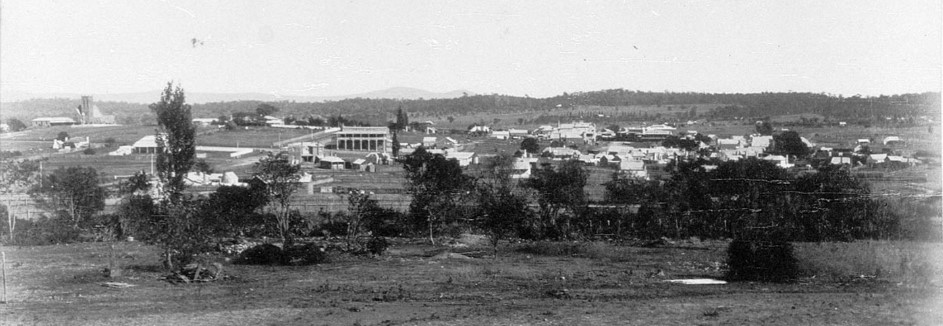

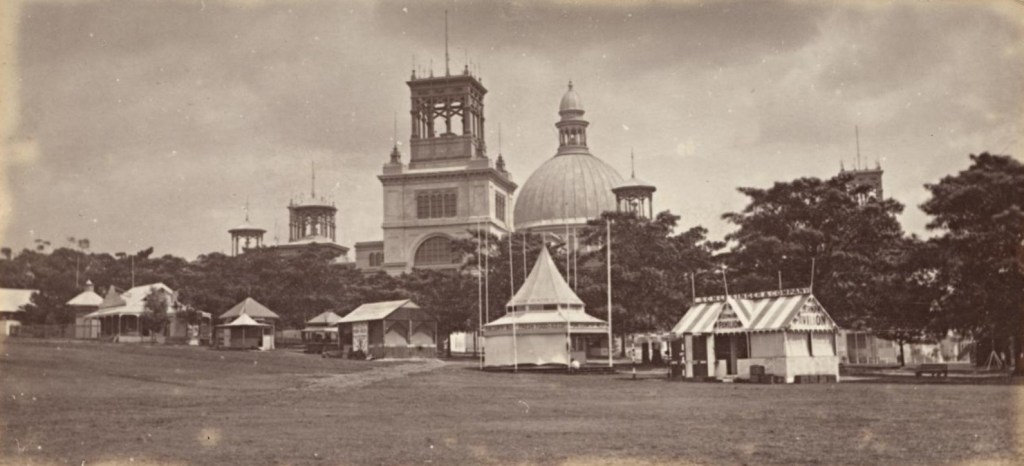

Dr Cumming’s neighbourhood in the 1880s.

By the 1880s, he was still practicing medicine, but was getting on in years. He sold his pony and cart and used public vehicles when visiting, but he kept doctoring on as best he could. [xxx] He was active in the Burns Society, and a respected member of various community and special interest groups.

In 1887, he published a book of poems. Or rather one very long poem with a couple of extras thrown in to make the total pages an even number. His topic was the Sydney Garden Palace, a long-lost beauty spot.

The Illustrated Sydney News was terribly polite, but barely enthusiastic:

“THE Sydney Garden Palace, so long defunct, has now been commemorated by a volume of verse written by Dr. Frederick Cumming. The volume is dedicated to the Queen, and adorned with a frontispiece of the Garden Palace, as it appeared before its destruction. To keep faith with the public, and to satisfy the expectations raised in the public breast by the promise of “4000 lines” made in the “Dedication,” the author has superadded to the Garden Palace poem a shorter work, entitled “Cupid in Eden.” In the narrative portion of the poem, Dr. Cumming has allowed himself considerable license in both rhyme and metre, but in some of the interspersed ballads and lyrics, where he has confined himself to a greater regularity of form, his versification is melodious and easy. The book is published by Messrs. Stewart & Co., of George Street, Sydney.“[xxxi]

The Sydney Morning Herald could not resist publishing this extract:

“Juvander and his Daisy Kate

Sat gazing on the sea-

‘How calm, how sweet the ocean is?

So may our joint lives be!’

Enthusiastic was that youth

Enamoured of Daisy.”[xxxii]

The cheeky sods at the Sydney Evening News went one better:

“On 24th of June, a drunken sot,

Deprived his wife of life by a gunshot.” [xxxiii]

Dr. Cumming had his adherents, though, and continued to dabble in verse and prose. Ill-health led to his retirement from active medical practice in 1887, and he died in 1891. [xxxiv] His passing was not noted in Queensland, which is a shame, given the efforts he made, and insults he endured, on behalf of the colony. In New South Wales, he was remembered, though.

Death of an Old Colonist

The numerous friends of an old colonist, Dr. Cumming, will regret to hear of his death, which took place at his residence at ‘Grosvenor,’ Petersham. The deceased gentleman came of a good old Scotch family, being born at Dundee in 1807. After passing his medical curriculum he voyaged round the world, and eventually returned to London, where he married the daughter of a rich city merchant. The gold fields of Australia, however, had a charm for him, and he accordingly left England to seek his fortunes in this new land. He in company with his wife and young family arrived by the ship Monsoon, of which vessel he was surgeon. He began the practice of his profession at Ipswich, Queensland, and subsequently practised at Toowoomba and at Brisbane. Some time afterward he returned to Scotland, where he was banqueted by the citizens of his native town. On his return to the colonies, by the ship Jason, he was appointed physician to the Grenfell Hospital, and he afterward followed his profession at Ryde, Parramatta, and Woollahra. Mental trouble eventually brought on an attack of paralysis, which rendered him helpless, and to which he succumbed after lingering for about four years. He published a number of poems of considerable merit, and was the author of other works which won favourable criticism. [xxxv]

It’s perhaps appropriate that the last mention of him in Queensland came from the Notices to Correspondents page of the Telegraph, years later:

“To Correspondents. Fair Play. — Declined. The admission of correspondences on the subject would lead to a deluge. Dr. Cumming has been dead many years.”[xxxvi]

[i] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Tuesday 12 November 1861, page 2

[ii] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Tuesday 18 February 1862, page 2

[iii] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Monday 10 March 1862, page 2

[iv] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Monday 10 March 1862, page 2

[v] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Saturday 16 August 1862, page 3

[vi] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864)Friday 29 August 1862 – Page 2

[vii] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864)Saturday 30 August 1862 – Page 2

[viii] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld. : 1861 – 1908) Friday 5 September 1862 – Page 3

[ix] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864) Tuesday 9 September 1862 – Page 2

[x] North Australian and Queensland General Advertiser (Ipswich, Qld. : 1862 – 1863)Tuesday 23 September 1862 – Page 2

[xi] Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) Thu 24 Sep 1863. Page 2

[xii] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864) Mon 26 Oct 1863, Page 2

[xiii] Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864) Fri 4 Mar 1864, Page 2

[xiv] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933) Thu 21 Apr 1864, Page 1

[xv] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 5 June 1866, page 2

[xvi] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Monday 9 July 1866, page 2

[xvii] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Saturday 22 December 1866, page 8

[xviii] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 5 February 1867, page 2

[xix] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 25 June 1867, page 2

[xx] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Saturday 18 January 1868, page 1

[xxi] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Saturday 1 February 1868, page 5

[xxii]Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Monday 24 February 1868, page 3

[xxiii] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933) Sat 28 Mar 1868 Page 8

[xxiv] Nashville Times, Gympie and Mary River Mining Gazette (Qld. : 1868) Wed 25 Mar 1868. Page 2

[xxv] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 16 June 1868, page 3

[xxvi]Queensland State Archives Item ITM 3722799

[xxvii] Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Saturday 16 December 1876, page 10

[xxviii] Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 – 1931) Mon 3 Sep 1877. Page 3

[xxix] Cumberland Mercury (Parramatta, NSW : 1875 – 1895), Saturday 6 July 1878, page 5

[xxx] Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954)Friday 19 November 1886 – Page 9

[xxxi] Illustrated Sydney News (NSW : 1881 – 1894), Monday 15 August 1887, page 23

[xxxii] Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Thursday 11 August 1887, page 4

[xxxiii] Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 – 1931), Thursday 11 August 1887, page 4

[xxxiv] Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Monday 12 January 1891, page 1

[xxxv] Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 – 1931), Friday 16 January 1891, page 3

[xxxvi] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Saturday 13 November 1897, page 6