On Saturday 19 December 1846, the Moreton Bay Courier published news of a terrible occurrence on the Darling Downs:

FATAL OCCURRENCE.—A short time ago, a Robert Tomlinson, a farm servant in the employ of Mr. Neill Ross, of Darling Downs, was reaping in the wheat paddock, a green snake bit him on the hand. On finding himself wounded, the poor fellow immediately proceeded to Mr. Ross’s residence, where every assistance was rendered; but as he positively refused the courageous offer of Miss Mary Ross to cut out the wounded part with a razor, human aid was of no avail and after suffering the most excruciating pains, he shortly expired.

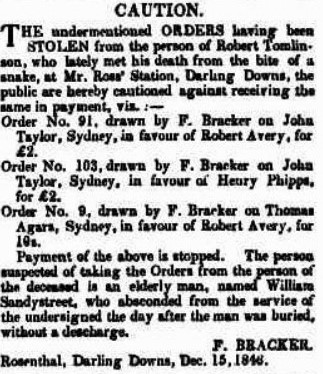

A week later, an advertisement ran in the Courier, advising that the late Robert Tomlinson had also been robbed, poor chap.

The news of Robert Tomlinson’s death reached Sydney and other parts of the colony by steamer. It was republished in late December, tucked away under a lengthy piece about Dr. Leichhardt’s progress towards the Swan River, and above news of an indigenous man being shot dead by Moreton Bay settlers on suspicion of being involved with the death of a white man.

According to the custom of the time, Mr. Tomlinson would have had a quick burial on the station, with the station manager saying the form of service. Ministers of religion were scarce in that largely unpopulated area. With so many jobbing station workers about, it was unlikely that the manager had any details of Mr. Tomlinson’s next of kin who might need to be notified.

A visit from beyond

Nothing more was heard of the matter, as far as newspapers were concerned, until in July 1847, Mr. Robert Tomlinson walked into the office of the Moreton Bay Courier, and asked Messrs. Lyon and Wilkes to kindly correct the report of his death. And to please explain how the report came to be published.

It transpired that Mr. Tomlinson had been residing in Sydney at the time of his death on the Darling Downs, and that the unfortunate man who had passed away was a Mr. Robert Avery. (The Courier didn’t specify exactly when they found out the dead man’s real name.)

Mrs. Robert Tomlinson, who appears not to have cohabited with her husband, read of his demise in the papers, and did what she felt was necessary in the situation. She took the large sum of money sent by his grieving family in England – some £300 – and married another man. She refused to leave said other man, or to hand over the Tomlinson family money. She was a widow. It was in the papers.

Mr. Tomlinson was on his way to Sydney to recover his money, but probably not his wife, and was at pains to point out to the Courier that their inaccurate reporting had more or less ruined his life.

It’s your fault for not telling us you weren’t dead

Naturally, Mr. Lyon and Mr. Wilkes were aghast at the consequence of their report, but they really didn’t feel that it was their fault.

Now, although we have to express our regret that we should have been unwittingly the means of publishing a report detrimental to his interest, and which must have given very great annoyance, he has himself to blame for not giving us an opportunity to contradict the rumour of his death, at the earliest moment.

Moreton Bay Courier, 17 July 1847

Rumour of his death? They had stated that Tomlinson was dead, in no uncertain terms. Yes, the mistake was initially that of whoever informed the Courier of the identity of the snake bite victim six months earlier. The editors had been informed that the deceased was Mr. Avery, but hadn’t thought to publish a correction.

And for students of management, this is called blame-shifting, or blamestorming. In those less litigious days, the Courier was not sued out of all existence, and the matter of the man who didn’t die was neatly dealt with – apart from a waggish account in the Sydney Morning Herald, that quoted a music-hall song: