It’s a different, but equally terrible, story.

The Stranger

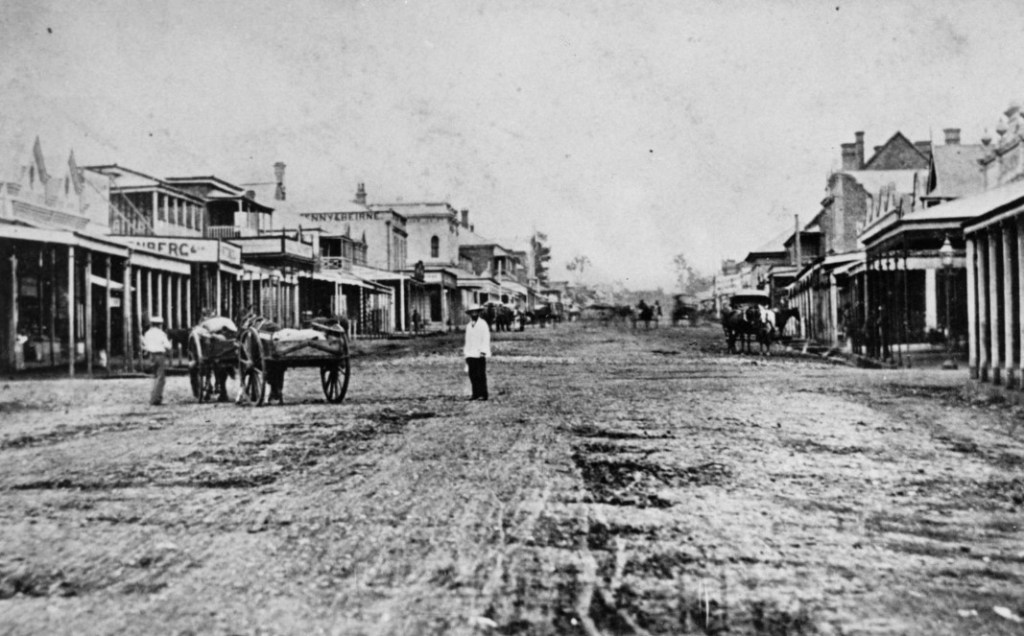

In the early evening of 19 June 1865, several women were followed about the streets of Toowoomba by a strange man. Some were violently assaulted.

At 6:00 pm, Ann Ward was going out of the front door of her cottage in Perth Street when she noticed a strange man at the gate, staring at her. Her husband was not at home, and she escaped the stranger’s gaze by running through the stockyard. The next time she dared to look, the man was still lingering by the gate. Then he gave up, and walked off in the direction of Hume Street.

On Hume Street, a servant to Thomas Daly, Catherine Flanagan, was walking back to her employer’s house with his daughter, Esther Daly. It was around 7:00 pm. A man began following them, then grabbed Catherine Flanagan about the shoulders. She managed to get free. The little girl screamed, and the man ran off.

Just after 7:00 pm, Barbara Peardon and Mary Ellen Cauldwell encountered the stranger as they turned from Perth Street to Ruthven Street. Mrs Cauldwell was grabbed by the head from behind. He dragged her away and forced her head between his knees. Mrs Peardon screamed, and the man let go of Mrs Cauldwell, and ran off down Ruthven Street. Mary Ellen Cauldwell ran to the nearby house of Rev Mr Waraker or shelter, followed a few moments later by Barbara Peardon, who had been briefly rooted to the spot in her terror.

The ladies spent about a quarter of an hour at Mr Waraker’s place recovering from the shock, and that kindly gentleman escorted them home. As they were leaving his house, a sharp scream was heard further down the street, followed by silence.

Margaret Curtis, wife of a horse drover, was headed home after a trip to the stores to sell some butter, and buy some tea, sugar and a blanket. She had given birth to her second baby just three weeks before, but was in good health and spirits, so a walk into town was no trouble. Her husband John had stayed home to look after their two daughters, and Margaret had stopped by her sister-in-law’s residence with her groceries and had a chat on her way home.

Around 7:45 pm, John Heppler and Leonard Armstrong were on their way home from working at Mr Fisher’s when they saw what they thought was a drunk lying in the street. On closer inspection, it was a young woman, dead but still warm, lying near a sliprail in Ruthven Street. She was lying on her face, her arms were crossed across her back, and her legs were also crossed. Her skirts were drawn up to the hips, exposing her legs. Whoever she was, she wore a black hat, a wincey dress and had a shawl wrapped tightly around her neck. A bag of groceries was found across the road.

The men immediately ran for the constables, who brought a doctor to the scene. It appeared to Constable Murphy that the woman had been dragged across the street, judging by the dirt on her face and the disarray of her clothes. Dr Stacey confirmed that life was extinct, and noticed some bruising about her face. He had her transported to the dead house for a post-mortem the following day.

When the post-mortem was conducted, it was confirmed that the deceased was Mrs Margaret Curtis, and that she had been strangled to death, after a terrific struggle to avoid a sexual assault. Margaret Curtis always wore two rings – her wedding ring and a “keeper.” They were not on her person when she was examined, and Heppler did not see them when he discovered her body. The rings were never found.

An inquest was ordered and was adjourned to allow the police to locate a stranger who it was thought had killed Mrs Curtis and attacked the other women that night. Someone answering to the description had been seen around the tollbar on the Toowoomba Range.

The Description

The official description of the man who attacked the women in Toowoomba was “about five feet seven inches high, black whiskers and moustache, had on, when last seen — a black or brown hat, which he pulled down over his face to escape observation, a black short coat or monkey jacket buttoned up to the chin, and black trousers.”

A California hat

Ann Ward: “the man in question had on a black felt hat, what they call a Jim Crow or California hat, a black monkey Jacket[i] rather worn, and dark trousers he seemed to be about 5 feet 6 or 8, in height and stooped a little. I only saw the side of his face, and he seemed to have dark whiskers. He did not seem drunk; he walked away gently and leisurely. The man looked dirty-looking.”

An American sailor in a monkey jacket.

Catherine Flanagan: “He seemed to be a stout man, about same height as prisoner, black clothes and a low black hat.”

Barbara Peardon: “He was a stout, short-looking man, his clothes were dark, he did not seem to be tall. I never saw his face at all; his coat seemed to be a monkey jacket, black and buttoned up, and he wore dark trousers.”

Mary Ellen Cauldwell: “I could not recognise the man; I only saw he was dressed in dark clothes.”

The Suspects

The Toowoomba Police, comprising two constables and a sub-inspector, set about finding a man that matched that description. A telegram went out to police stations in the Moreton Bay area. All the leads they had were followed up.

William Barber

The first man to be arrested on suspicion was William Barber, who was walking along Brisbane Street, Ipswich on 23 June 1865. Constable Elligett of the Ipswich Police had seen the telegram from Toowoomba, and arrested Barber because he resembled the description of the suspect. Despite his protests that he had just arrived from Brisbane and knew nothing of the murder, Barber was locked up, and brought before the Ipswich Bench.

Fortunately for William Barber, he had alibi and identity witnesses who were able to attend and give evidence as to his whereabouts. James Tapson had sailed with Barber from Sydney on the steamer Florence Irving on the 16th June, and they had arrived in Brisbane on the 19th. They had lodged together, and only parted company on the 22nd June. Barber’s brother was able to corroborate this,

William Barber was discharged without any stain on his character.

James Munroe

The second suspect to be brought before the justices at Ipswich was a far less straightforward character. He had been released from Toowoomba Gaol on 16th June 1865 and had apparently made his way down the Range and through the Lockyer Valley, where he drew the attention of fellow-travellers and locals. Based on gossip about Munroe hanging around and acting strangely, Mr O’Brien had detained Munroe at the Seven-Mile creek homestead and sent for the constables.

Another traveller, who couldn’t subsequently be located, told Mr O’Brien that a vest had been found on the road, and in its pocket was a gold ring. No trace of the vest was ever found, and it was not able to be linked to Munroe.

While at Seven-Mile, Munroe refused to answer any questions. He was given in charge to the police at Ipswich, and told them strange things, including that he was in love with a girl named Anna Maria Scott, who he claimed to have seen “in a form” and carrying a basket on the Toowoomba Range.

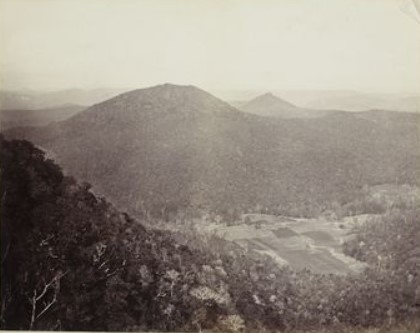

The Toowoomba Range, c. 1880 (SLQ).

The women who had been stalked and attacked on the night of Margaret Curtis’ murder were asked whether he was the man they had seen.

Ann Ward : “He did not speak to me; the man was stout, with broad shoulders, and stooped a little; he did not look at all like prisoner. I do not think I should be able to recognise the man again.”

Catherine Flanagan : “The prisoner now before the Court is not the man at all; I would not know the man if I saw him; he did not speak at all.“

Barbara Peardon : “The man did not speak; the prisoner before the Court is not the man.”

Mary Ellen Cauldwell : “I did not catch hold of the man, he did not speak.”

(The reason for the reference to speech became clear when Munroe finally gave some personal information – he would have had a pronounced Scottish accent.)

William Murphy, the Toowoomba Gaoler, was able to confirm that the man before the court was James Malcolm Munroe, who had been sent to Toowoomba Gaol on the 7th June from the Condamine, after he failed to find sureties to keep the peace. Munroe had been charged with threatening to stab a man there. On his release, at 10 am on the 16th June, Munroe wore a grey tweed coat and trousers, did not possess a vest, and had no money or personal possessions. He had not, in Murphy’s opinion, shown any signs of insanity while in Toowoomba Gaol.

Munroe refused to say anything beyond that he was not guilty of the murder. The coroner was not having any of this. He questioned Munroe directly, under caution, and slowly and painfully elicited the information that James Malcolm Munroe had been in the colony 3 years, was aged 24, had been a lithographer, and was Scottish by birth. He said he had left Toowoomba on the day he was released and was on his way to Ipswich. He admitted that he told the Ipswich sub-inspector about Anna Maria Scott, but hadn’t told him that he had heard that she was dead.

At the close of the inquiry, the coroner was about to give a lengthy summing-up of the evidence, when the jury foreman told him that they had arrived at a verdict.

“That the deceased, Margaret Curtis, was found dead in Ruthven-street, Toowoomba, on the 19th instant, and that she was wilfully murdered by some person or persons unknown.”

The close of the inquest saw the case gradually fade from the newspapers, although the police were still looking for Mrs Curtis’ killer.

James Munroe was discharged, only to be re-arrested the same day for his own protection. He was ordered to be sent to Woogaroo Asylum for treatment, on the suspicion of being of unsound mind.

On admission to Woogaroo on 18th July 1865, Munroe was described as being quiet and melancholy. By the end of that year, he was assessed as “an incurable case.” In 1868, his record was noted that he was in good health, but the same state of mind. He died on 26 February 1871.

Further Arrests

Gotfried Wielbrecht

In March 1867, the people of Toowoomba were startled to find that two men had been arrested for the murder of Mrs Curtis two years earlier. One was a German man, Gotfried Wielbrecht, who had lived in Toowoomba two years earlier but had left. The other man did not rate a mention of his name, but he turned out to be local ne’er-do-well, Michael Ford. The Courier and the Darling Downs Gazette reported breathlessly that –

“The police are said to be in the possession of evidence strongly tending to criminate him, but which, for the furtherance of the ends of justice, it is held necessary to keep private.”

The men were brought up on 3rd April 1867 at Toowoomba, but “there being no evidence of sufficient importance” against them, they were discharged. The much-vaunted evidence seemed to have been wishful thinking. Wielbrecht was put on a personal bond of £40 to appear if called upon within one month.

After his discharge, Gotfried Wielbrecht returned to South Australia, where his case had been reported on in a German-language newspaper. He was married there a month later, and nothing ever came of the Toowoomba charge.

Michael Ford

Michael Ford had spent a fair bit of time in Toowoomba in 1865, generally getting drunk and being arrested. He removed to Roma, where, in 1868 he took up a side hustle as a police informant. The Roma correspondent of the Darling Downs Gazette described Ford as a “disgusting character,” and brought up the 1867 arrest and discharge as proof of same. It appears that Mr Ford was in the habit of making accusations of sly grog trading against persons of hitherto unimpeachable character, and that the Roma Bench was in the habit of taking him at his word. Ford, the Gazette alleged, was trying to work up a passage to America, and would do so by fair means or foul. Ford would later spend a month in Toowoomba Gaol for being illegally on premises (he was drunk at the time) and may have been the Michael Ford involved in a horse-stealing gang around Dalby.

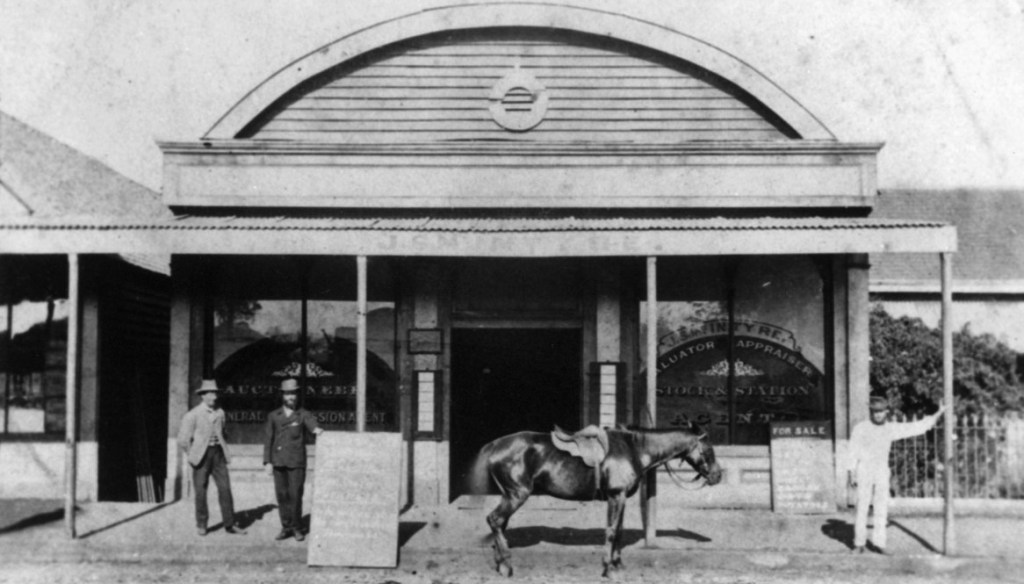

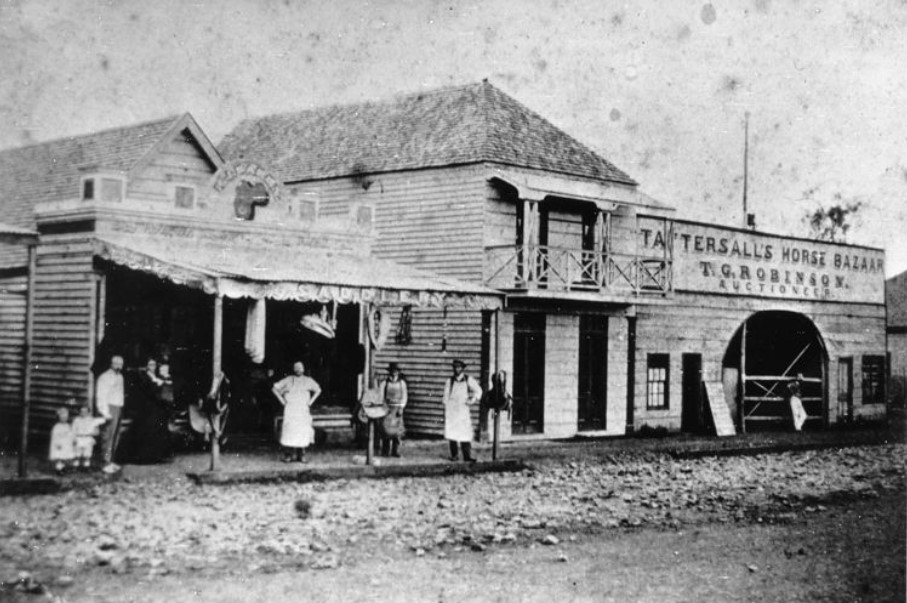

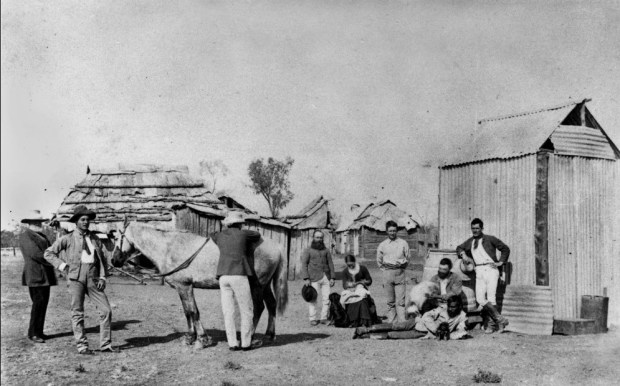

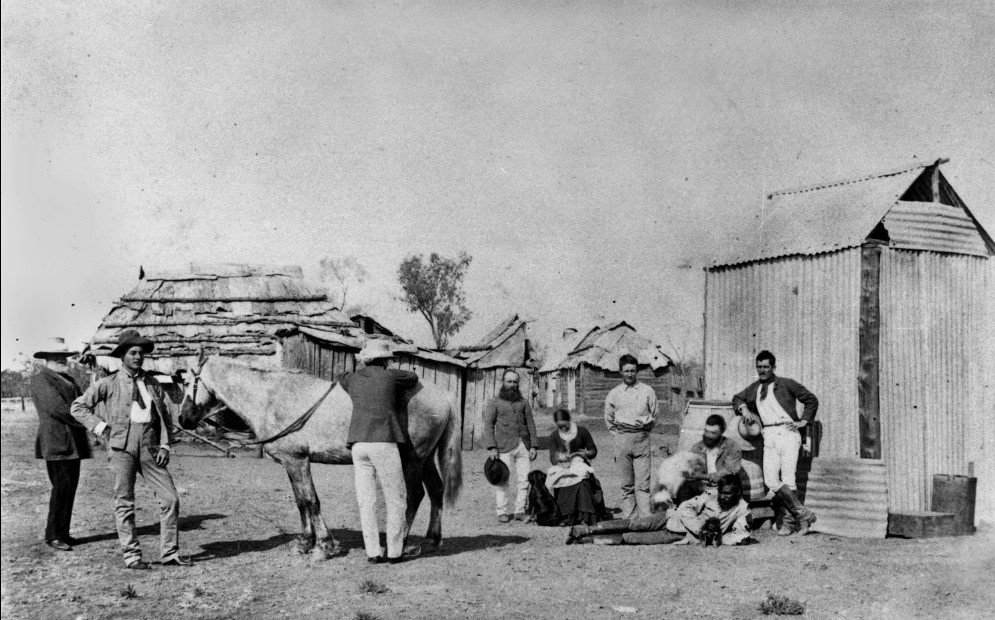

Station Workers at Roma, 1867 (who knows – Michael Ford may be here?) (SLQ)

Again, the trail went cold. Dame Rumour took over updating the public in the following years.

Rumours of a Deathbed Confession

In February 1874, the Toowoomba Chronicle reported that there had been a deathbed confession to Margaret Curtis’ murder. Or two.

The first confession, rumour declared, came from a man who had died in North Queensland recently. He had, it was said, courted Margaret Curtis before her marriage, and was bitter at not being chosen.

The second confession was allegedly made in Dalby by a dying man attended to by a priest. That man, the Chronicle declared, had passed away in early February.

Then, in order to confuse everyone, it was reported that the man who made the confession (either the one in Dalby or in Far North Queensland), was alive and recovering in Rockhampton. And presumably not implicating himself in the Toowoomba murder. The Chronicle went to the proper authorities for clarification, but the authorities had heard nothing of the sort.

Was There a Written Gaolhouse Confession?

Burdett, or the Widow Welsh

In December 1875, the Courier and the Darling Downs Gazette ran articles alleging that a man named Charles Burdett, alias the Widow Welsh, had made a written confession to the murder of Mrs Curtis a decade earlier. Burdett was in Berrima Gaol, apparently in the throes of a terrible illness, and had declared that he was one of two men who had committed the murder. Apparently, Burdett named the other man in this document. His photograph was being sent to the Toowoomba police. All of the town and city newspapers in Queensland ran this item, and it was picked up by a regional New South Wales paper as well.

Charles Burdett alias Charles Welsh alias Widow Welsh was a Sydney resident in the 1870s. He ran a mail-order business, selling Widow Welsh’s Pills, a product advertised for “Female Troubles,” that was claimed to “remove all difficulties.” In other words, he peddled abortion pills.

In 1874, Charles Burdett was arrested, along with a Doctor Sir John van Heekeren (real name: James Beaney), on charges relating to a young woman’s illegal abortion. The woman had gone to Burdett, and taken the recommended pills, but rather than inducing an abortion, they made her ill. Burdett referred her to van Heekeren, who performed a procedure that succeeded in terminating the pregnancy. Widow Welsh’s Pills were famous, and the case against Burdett was a sensational one. He received seven years’ imprisonment to perform hard labour on the roads and public buildings of the colony, and his co-defendant walked free.

In October 1875, Burdett was transferred from Parramatta to Berrima Gaol. He sent several petitions to the Colonial Secretary in 1878, both of which were returned with the note that His Excellency did “not see fit to authorise the remission of any part of the prisoner’s sentence.”

Burdett was released from gaol, but the mysterious written confession was never actively followed up by the police in either Queensland or New South Wales. Possibly because it didn’t really exist.

In 1880, Burdett was arrested again on the same charge, but with a different co-defendant. After a committal hearing, the Attorney-General decided not to file a bill, and Burdett escaped further conviction.

There is no evidence that Charles Burdett or Welsh ever resided in, or visited, Toowoomba. Charles Burdett’s name was on the passenger list of a steamer called the Telegraph, which departed Brisbane for Sydney in September 1867.

Who “Charles Burdett” was is hard to uncover. He bore the same name as a Baronet – Sir Charles Francis Burdett – who was a relative of the ridiculously wealthy and devoutly charitable Angela Burdett-Coutts. (The real Baronet Burdett-Coutts was a resident of Wellington, New Zealand in his later years, and died in poverty after failing at just about every enterprise, including flower theft.)

On Burdett’s admission to Darlinghurst in 1874, he was described as 35 years of age (although the court reporter stated his age as 44), born in America, 5 feet 7 inches, and who arrived via the steamer Otago in either 1854 (one page) or 1868 (another page). His occupation varied according to the register he was entered in – it was “teamster” in one, “ship-owner” in another. Burdett claimed to have been a ship’s surgeon on the troop ship Himalaya, but also took pains not to present himself as a Doctor of Medicine when dealing with the women who consulted him.

What became of him after 1880 is a mystery. He may have fled the colony. He was recalled by a man writing under the pseudonym “Mark Meddle” in the Truth in 1903: “Burdett was a short, fat man, unctuous, greasy in appearance, with dark, well-oiled hair hanging over his neck. In appearance he was unhealthy, repulsive, and not by any means angelic.” It was reported that he had long since joined the “great majority.”

Could One of the Suspects Have Committed the Crime?

James Barber: he wasn’t even in the right town at the time.

James Munroe: he was mentally ill and had been in the region at the right time. However, he was positively ruled out by eyewitnesses, and did not have the right clothing.

Gotfried Wielbrecht: there wasn’t enough evidence to pursue any charges. There is no record of why the police suspected him.

Michael Ford: he was definitely in Toowoomba at the time, but his other crimes seem to involve drunkenness, rather than violence. He was also discharged by the Bench for want of evidence.

Charles Burdett: there is no evidence that he was in Toowoomba at the time, or that he really made a written confession. He seems to have been a con-man and abortion-pill peddler, rather than a man who would assault women in the street.

Deathbed Men: Once “well-known” residents of Toowoomba allegedly, meaning that they would have been easy to recognise when pestering the Barbara Peardon and the other ladies. If it was a rejected suitor, did he see Margaret Curtis walking through town with her shopping and decide to strike a fatal blow? Hardly, a resident of Toowoomba would have seen her about the place on a regular basis.

Margaret Considine Curtis

The murder remains unsolved, which must have tortured her husband and family. It’s only fair to the victim to give an account of her short life and family.

Margaret Considine (1837-1865) was born in County Clare, Ireland in 1837. Her parents were Norah Keefe and Michael Considine. She married John Curtis (1838-1914), a native of Galway, on 30 September, 1862 in Brisbane.

The couple’s first child was a girl named Catherine, who was born on 15 July 1863. She was probably named after her Aunt Catherine, who was the last person to see Margaret alive.

Their second daughter, Honora, was born on 30 May 1865, and was just three weeks old when she lost her mother. Little Honora passed away in November 1865.

The townspeople of Toowoomba rallied around John and his young family. They helped out with the funeral and burial costs and looked in on the widower.

John Curtis married again, in 1867, to Mary Lee (1848–1919). They had thirteen children.

[i] A monkey jacket is a waist length jacket tapering at the back to a point. Use of the term has been dated to the 1850s onwards.[1] Wikipedia

Thank you for this interesting read. I have been also trying to find info on Burdett and his sister Amelia Miller who lived in Liverpool Street. According to his probate records, Burdett died at sea on the SS Changsha steamer in 1897. Strangely he leaves his estate of c 287 pounds to Gertrude Burdett, his wife living in Hamburg, Germany. He interests me because Abraham van Heekeren is my maternal ancestor. He was an actual doctor, having graduated from Westphalia University, with one of the first gynaecology schools. He is from Amsterdam born 1827, went to New York after his graduation and left and arrived in Sydney in Aug 1863. By 1885, he and all but his eldest son, leave for San Fransisco. He eventually moves to Portland Oregon in 1890 and he died there in 1915. I am intrigued by the suggestion he was also known as James Beaney. I can’t find the evidence for this but if you have some I would be most grateful. I think both of them were slippery customers so anything is possible. I agree with you that that it is highly unlikely Burdett commuted the murder. I think the ravings of a very unwell man.

Thanks

John Summers

LikeLike